Abstract

Objectives

Q fever is a zoonosis caused by the bacterium Coxiella burnetii. It is recognised as an occupational hazard for individuals who are in regular contact with animal birth products. Data from the literature are not comparable because different serological assays perform very differently in detecting past infections. It is therefore essential to choose the right assay for obtaining reliable data of seroprevalence. Obstetricians are another profession potentially at risk of Q fever. They can be infected from birth products of women with Q fever during pregnancy. There is little data, however, for Q fever in this occupational group. Our study therefore had two purposes. The first was to obtain reliable seroprevalence data for occupational groups in regular contact with animal birth products by using an assay with proven excellent sensitivity and specificity for detecting past infections. The second purpose was to obtain primary data for obstetricians.

Design

We carried out a cross-sectional study.

Setting

The study included shepherds, cattle farmers, veterinarians and obstetricians from Thuringia.

Participants

77 shepherds, 74 veterinarians, 14 cattle farmers, 17 office employees and 68 obstetricians participated. The control group consisted of 92 blood donors.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was C. burnetii phase II specific IgG. The assay used was evaluated for this purpose in a previous study.

Results

Of the 250 blood samples we analysed, the very highest seroprevalences (64%–77%) occurred in individuals with frequent animal contact. There were no significant differences between shepherds, cattle farmers and veterinarians. The seroprevalence in people working in administration was lower but still significantly greater than the control. No obstetricians or midwives tested positive.

Conclusions

Shepherds, cattle farmers and veterinarians have a high risk of C. burnetii infection. However, our study clearly proves that there was no increased risk for people working in an obstetric department.

Keywords: shepherd, veterinarian, obstetrician, cattle farmer, Coxiella burnetii

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Undertook a cross sectional study using a serological test with proven excellent performance for this purpose.

Investigated different professional groups with reliable sample sizes.

First investigation of people working in an obstetric department.

The study was limited to a single centre.

Non-random sampling may lead to a bias towards high Q fever seroprevalence.

Introduction

Q fever is caused by the bacterium Coxiella burnetii. The disease has re-emerged as a significant public health issue in Europe as has been demonstrated by several outbreaks.1–4 The largest of these affected up to 4000 people in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2009.1 The symptoms of human Q fever are non-specific and the acute disease presents as febrile illness, a flu-like syndrome or pneumonia.5 6 But the acute disease may pass by asymptomatically. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections can become chronic, causing endocarditis or vasculitis associated with a high mortality rate.7 Most outbreaks are associated with sheep, cattle and goats8–10 where C. burnetii can be found in high numbers in the amniotic fluid, placenta and foetal membranes of infected animals.11 The extracellular survival form of the bacterium (small cell variant) is highly resistant to environmental stresses such as desiccation.12 This means it can persist in the environment for weeks.13 Human infection then typically occurs by inhalation of contaminated dust or aerosols.14 Infection with C. burnetii is an occupational hazard for those who are regularly in close contact with animal birth products. Such groups include farmers, veterinarians, and workers in zoos or abattoirs.15

C. burnetii can also be found in the birth products of women with Q fever during pregnancy and can cause perinatal infections of obstetricians.16 But there are uncertainties about the real risk.

A meta-analysis of C. burnetii seroprevalence among abattoir workers revealed significant heterogeneity among serological tests.17 Different tests also gave very different results for the same people in our evaluation of commercial tests for the detection of past infection.18 Excellent performance was only found for the Panbio-ELISA (PanbioDiagnostics, Korea).18 We therefore used this assay to get reliable seroprevalence data for occupational groups with close animal contact and to obtain primary data for people working in an obstetric department.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study between 2009 and 2016 that included several at-risk groups. We initially focused on shepherds and veterinarians but offered testing to all interested people. Between 2009 and 2010 we recruited shepherds and veterinarians at several educational meetings of the occupational union for shepherds. And in 2010 we recruited among veterinarians, and also among cattle farmers and office employees, attending a congress for cattle farmers in 2010 (41 of 165 congress participants participated, 25%). In all we were able to include 84 out of about 400 professional shepherds in Thuringia in 2009 and 2010 (21%). The group of office employees consisted of animal welfare inspectors (Tierschutzkontrolleur) and veterinarians, all of whom had sporadic animal contact. In 2011, resampling of blood from people infected with C. burnetii during an outbreak 6 years previously allowed us to evaluate serological assays for the detection of past infection.18 This outbreak with 331 cases occurred in a densely inhabited area of Jena, a town in Thuringia.2 As a result of the validation we found only one assay suitable for seroprevalence studies. We retested all the sera sampled and enlarged the group of veterinarians to obtain a reliable sample size. We increased the number of veterinarians by including some of those attending a number of educational meetings on veterinary medicine and animal health in 2016. To examine the question of the risk for obstetricians, we added this occupational group to our study. We did this by attending educational meetings of the occupational union of midwives (proportion of participants is not available). In addition, between January and August 2016, we offered C. burnetii-specific antibody testing for all staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital Jena (34 out of 50 employees took part, 68%). After obtaining written informed consent, we interviewed people in the different occupational groups. We recorded information about occupational history and contact with sheep, goats and cattle. We specifically asked the participants how long they had been in their occupation and how much they were exposed to ruminants. As most of the shepherd grew up with intense animal contact, we chose the length of sheep contact instead of working years for this special group. A blood sample was taken from every interviewee and the sera were stored at −80°C until antibody testing. Sera of 92 blood donors were tested as a control group. The blood donor group consisted of 22 women and 70 men with an average age of 35 (range 18–67). All members of this group lived in urban areas

We analysed the sera for C. burnetii-phase II-specific IgG antibodies with the Panbio-ELISA. The Panbio-ELISA assay was conducted manually according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The optical densities were read at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 620 nm (Sunrise, Tecan).

For all calculations we used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS V.21). The seroprevalences of the different groups were compared using the chi-squared test.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the conceptualisation or carrying out of this research. Study participants received their personal results and recommendations by letter.

Results

A total of 250 people participated in our study (table 1). The sex ratio of the different occupational groups ranged from 99% females in the obstetrician group to 90% males in the shepherd group.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii-phase II-specific IgG in different occupational settings

| Group | n | Female:male | Age (range) (years) |

Time of exposition* (range) (years) |

Proportion† (%) | P value |

| Blood donors | 92 | 2:7 | 35 (18–67) | 2/92(2.2) | Reference | |

| Shepherds | 77 | 1:9 | 45 (19–70) | 28 (0–62) | 59/77(76.6) | <0.001 |

| Cattle farmers | 14 | 1:2 | 52 (32–65) | 31 (12–54) | 9/14(70.3) | <0.001 |

| Veterinarians | 74 | 1:1 | 45 (24–75) | 19 (0–50) | 52/74(64.3) | <0.001 |

| Office employees | 17 | 3:1 | 46 (26–56) | 23 (2–36) | 7/17(41.2) | <0.001 |

| Obstetricians | 68 | 99:1 | 44 (24–64) | 22 (0.5–45) | 0/68(0.0) | 0.221 |

*Occupational time, except for shepherds where the whole duration of sheep contact was used.

†Seroprevalence for C. burnetii-phase II-specific IgG.

The highest seroprevalences were found for people with frequent animal contact (64%–77%). There were no significant differences between cattle farmers, practising veterinarians and shepherds. The seroprevalence of people working in administration was lower than in those with frequent animal contact but still significantly greater than the control group. None of the obstetrician group was positive for past Q fever infection.

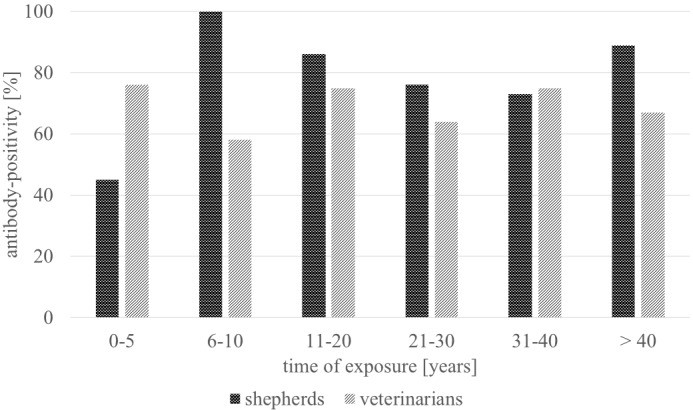

The time of exposure to sheep in shepherds ranged widely from 0 to 62 years (average 28 years). Even the duration of work with animals in the group of veterinarians ranged from 0 to 50 years (average 19 years). However, infection rates in these groups were high even after only a few years of exposure (figure 1) although the sample size of the different durations of exposure is very small.

Figure 1.

Antibody-positivity in relation to duration of exposure *shepherds: 0–5 years: n=5, 6–10: n=5, 11–20: n=6, 21–30: n=16, 31–40: n=11, >40: n=16 veterinarians: 0–5 years: n=13, 6–10: n=7, 11–20: n=9, 21–30: n=9, 31–40: n=9,>40: n=4.

Discussion

This is the first seroprevalence study investigating different occupational groups using an assay validated for detecting past Q fever. Most assays are designed as tools for diagnosing clinical disease but they give differing results in other contexts. Our evaluation of three different commercially available ELISA for detection of past C. burnetii infection revealed Receiver Operating Characte (ROC) curves that discriminated well between infected and uninfected individuals. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) ranged from 0.97 to 1.0 (18). However, most antibody levels during the convalescent phase fall under the cut-off titre, in accordance with the study by Blaauw.19 This phenomenon leads to sensitivities of 42 (Virion/Serion, Germany), 51 (IBL International, Germany) and 100% (Panbio Diagnostics, Korea) with specificity of 94%–100% six years after infection.18 Based on our evaluation data we chose the Panbio-ELISA (sensitivity 100%; specificity 94%) for our study.18

Cohort composition was based on sampling performed in different occupational groups and settings. The first specimens collected during 2009 and 2010 were tested with the Virion/Serion-ELISA and revealed questionable results. Several people with close contact to animals with Q fever history showed negative results, despite the high infectivity of C. burnetii. Knowing that the used assay was only evaluated for acute disease, we supposed an insufficient test performance for detecting past infection. Potentially antibody levels could have fallen under the cut-off. We evaluated different assays for this purpose and found the Panbio-ELISA of excellent performance for seroprevalence detection.18 We retested our samples and enlarged our study group until 2016. From the epidemiological point of view the rather long period of recruitment may bias our results. However, the actual stable living and working conditions of our study group especially the shepherds minimise the risk of bias. A potential bias due to non-random sampling cannot be ruled out as people aware of their Q fever contact in the past may have more interest in being tested than those without such awareness. However, this bias is likely to be similar for all the occupational groups investigated. Another limitation might be the restriction to one single centre.

We found very high seroprevalence, 70%, in people with close occupational contact with animals. Seroprevalence was also quite high, 41%, in the group of office employees even though they had only sporadic animal contact. However, half these people were non-practising veterinarians who had studied veterinary medicine. Because such students are at risk of Q fever,20 this finding must be investigated in more detail with a larger sample size. However, the remarkably high seroprevalences are reliable given the characteristics of the disease. There are enormous numbers of C. burnetii in some placentae (109/g) or milk (105/mL),11 the bacterium is highly infective (it has been estimated that a single organism is able to cause disease), it is highly resistance to environmental stresses (it survives on wool for 7–10 months12) and has a flock level prevalence of 28%.21

Seroprevalences in shepherds are generally 29%–59%22 23 and in veterinarians 10%–75%.24 25 However, these wide ranges are, in part, illusory because the values result from very different assays, in-house tests and even from tests using different cut-off values. In large seroprevalence studies in the Netherlands 18.7% of veterinary medicine students were antibody positive as were 66.7% of dairy and 51.5 of non-dairy sheep farm residents and 87.2% of cattle farmers.20 23 26 But the situation in the Netherlands differs from that in Germany as the general seropositivity in the population increased during the large outbreak in 2007. It was 2.3% in 2006–2007 but by 2009 was 25.1% in the epicentre of the outbreak and 12.2% in blood donors in the most Q fever-affected areas.27–29 Most of these Dutch studies used immunofluorescence (IFAT). IFAT is regarded as a reference method but several cut-off titres are used and so standardisation is required if they are to be used in seroprevalence studies.19 The only other study using Panbio-ELISA produced results similar to ours with 78% for veterinarians and 54% for cattle farmers in Sicily.30

Keeping in mind that more outbreaks are related to sheep than to cattle, it is interesting that there was no difference in our study between people handling sheep and those handling cattle. But, to rule out significant bias, a reinvestigation of the group of cattle farmers with an enlarged sample size is needed. Our findings are in accordance with the finding of Marrie that slaughtering cattle is a significant risk factor for positive antibody titres.31 We did not include the interesting group of slaughterhouse workers in our study as there is no professional slaughterhouse for sheep in Thuringia. About 95% of sheep are slaughtered outside Thuringia. But a recent metanalysis demonstrates that this group has very high seroprevalences, of 30%–70%,.17

We found much lower seroprevalence in obstetricians than did the only published study available. This study from the 1970s in Bulgaria used a complement fixation test and revealed 37% positivity for obstetricians compared with 8% positivity in blood donors.32 The discrepancy probably arises from the high hygiene standards of modern obstetrics. The development of the infective and highly resistant form of C. burnetii (small cell variant) is promoted by desiccation. But obstetrical departments are frequently cleaned and disinfected and waste is rapidly disposed of so reducing the risk of the small cell variant spreading. However, the data for obstetricians should be repeated in another area with a larger sample size.

In conclusion, shepherds, veterinarians and cattle farmers, and even people with sporadic animal contact like employees in veterinary offices, have a high risk of C. burnetii infection. Physicians should therefore consider C. burnetii infection as a differential diagnosis for acute febrile illness as well as for endocarditis and vasculitis in these occupational groups. In contrast, our study clearly proves that there is no increased risk for people working in an obstetric department. The already high hygienic standards in obstetrical departments are sufficient to keep under control the occupational risk for Q fever.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr AJ Davis (EnglishExperience Language Services, Jena, Germany) for his excellent support in editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: TG and KB conceived the study. TG, KK, UM and KB designed the study. KK, UM and BH performed the experiments. TG, KK and KB analysed the data. UM and KM provided resources. TG, KK, BH and KB wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany (KB Grant 01 KI 0735, 01 KI 1001C).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital Jena (reference number 2525-04/09, 4615-11/15).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Extra data are available by emailing karola.kuenzer@med.uni-jena.de.

References

- 1. Delsing CE, Kullberg BJ, Bleeker-Rovers CP. Q fever in the Netherlands from 2007 to 2010. Neth J Med 2010;68:382–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilsdorf A, Kroh C, Grimm S, et al. . Large Q fever outbreak due to sheep farming near residential areas, Germany, 2005. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:1084–7. 10.1017/S0950268807009533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Porten K, Rissland J, Tigges A, et al. . A super-spreading ewe infects hundreds with Q fever at a farmers' market in Germany. BMC Infect Dis 2006;6:147 10.1186/1471-2334-6-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Varga V. An explosive outbreak of Q-fever in Jedl'ové Kostol'any, Slovakia. Cent Eur J Public Health 1997;5:180–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999;12:518–53. 10.1128/CMR.12.4.518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parker NR, Barralet JH, Bell AM. Q fever. The Lancet 2006;367:679–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68266-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Broos PPHL, Hagenaars JCJP, Kampschreur LM, et al. . Vascular complications and surgical interventions after world's largest Q fever outbreak. J Vasc Surg 2015;62:1273–80. 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.06.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clark NJ, Soares Magalhães RJ. Airborne geographical dispersal of Q fever from livestock holdings to human communities: a systematic review and critical appraisal of evidence. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:218 10.1186/s12879-018-3135-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hellenbrand W, Breuer T, Petersen L. Changing epidemiology of Q fever in Germany, 1947-1999. Emerg Infect Dis 2001;7:789–96. 10.3201/eid0705.010504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Georgiev M, Afonso A, Neubauer H, et al. . Q fever in humans and farm animals in four European countries, 1982 to 2010. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bell EJ, Parker RR, Stoenner HG. Experimental Q fever in cattle. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1949;39:478–84. 10.2105/AJPH.39.4.478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christie AB. Q fever : Christie AB, Infectious diseases: epidemiology and clinical practice. 800 New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson A, Bijlmer H, Fournier P-E, et al. . Diagnosis and management of Q fever--United States, 2013: recommendations from CDC and the Q Fever Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raoult D, Marrie T, Mege J. Natural history and pathophysiology of Q fever. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:219–26. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garner MG, Longbottom HM, Cannon RM, et al. . A review of Q fever in Australia 1991-1994. Aust N Z J Public Health 1997;21:722–30. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1997.tb01787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stein A, Raoult D. Q fever during pregnancy: a public health problem in southern France. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:592–6. 10.1086/514698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woldeyohannes SM, Gilks CF, Baker P, et al. . Seroprevlance of Coxiella burnetii among abattoir and slaughterhouse workers: A meta-analysis. One Health 2018;6:23–8. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frosinski J, Hermann B, Maier K, et al. . Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in seroprevalence studies of Q fever: the need for cut-off adaptation and the consequences for prevalence data. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:1148–52. 10.1017/S0950268815002447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blaauw GJ, Notermans DW, Schimmer B, et al. . The application of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescent assay test leads to different estimates of seroprevalence of Coxiella burnetii in the population. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:36–41. 10.1017/S0950268811000021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Rooij MMT, Schimmer B, Versteeg B, et al. . Risk factors of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) seropositivity in veterinary medicine students. PLoS One 2012;7:e32108 10.1371/journal.pone.0032108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hilbert A, Schmoock G, Lenzko H, et al. . Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii in clinically healthy German sheep flocks. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:152 10.1186/1756-0500-5-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dolcé P, Bélanger M-J, Tumanowicz K, et al. . Coxiella burnetii seroprevalence of shepherds and their flocks in the lower Saint-Lawrence river region of Quebec, Canada. Can J Infect Dis 2003;14:97–102. 10.1155/2003/504796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Lange MMA, Schimmer B, Vellema P, et al. . Coxiella burnetii seroprevalence and risk factors in sheep farmers and farm residents in the Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:1231–44. 10.1017/S0950268813001726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thibon M, Villiers V, Souque P, et al. . High incidence of Coxiella burnetii markers in a rural population in France. Eur J Epidemiol 1996;12:509–13. 10.1007/BF00144005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nowotny N, Deutz A, Fuchs K, et al. . Prevalence of swine influenza and other viral, bacterial, and parasitic zoonoses in veterinarians. J Infect Dis 1997;176:1414–5. 10.1086/517337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schimmer B, Schotten N, van Engelen E, et al. . Coxiella burnetii seroprevalence and risk for humans on dairy cattle farms, the Netherlands, 2010-2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:417–25. 10.3201/eid2003.131111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schimmer B, Notermans DW, Harms MG, et al. . Low seroprevalence of Q fever in the Netherlands prior to a series of large outbreaks. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:27–35. 10.1017/S0950268811000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karagiannis I, Schimmer B, Van Lier A, et al. . Investigation of a Q fever outbreak in a rural area of the Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:1283–94. 10.1017/S0950268808001908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hogema BM, Slot E, Molier M, et al. . Coxiella burnetii infection among blood donors during the 2009 Q-fever outbreak in the Netherlands. Transfusion 2012;52:144–50. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fenga C, Gangemi S, De Luca A, et al. . Seroprevalence and occupational risk survey for Coxiella burnetii among exposed workers in Sicily, southern Italy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2015;28:901–7. 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marrie TJ, Fraser J. Prevalence of antibodies to Coxiella burnetii among veterinarians and slaughterhouse workers in nova Scotia. Can Vet J 1985;26:181–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ganchev N, Serbezov V, Alexandrov E. Incidence of Q fever in two inadequately investigated occupational groups. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol 1977;21:405–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.