Abstract

Objectives

To describe changes in unplanned acute activity and to identify and characterise unplanned contacts in hospitals in Denmark from 2005 to 2016, including following healthcare reform.

Design

Descriptive study.

Setting

Data from Danish nationwide registers.

Population

Adults (≥18 years).

Participants

All adults with an unplanned acute hospital contacts (acute inpatient admissions and emergency care visits) in Denmark from 2005 to 2016.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Outcomes were annual number of contacts, length of stay, number of contacts per 1000 citizen per year, age-adjusted contacts per 1000 citizens per year, sex, age groups, country of origin, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, discharge diagnosis and time of arrival.

Results

We included a total of 13 524 680 contacts. The annual number of acute hospital contacts increased from 1 067 390 in 2005 to 1 221 601 in 2016. The number also increased with adjustment for age per 1000 citizens. In addition, regional differences were observed.

Conclusions

Unplanned acute activity changed from 2005 to 2016. The national number of contacts increased, primarily because of changes in one of the five regions.

Keywords: epidemiology, organisational development, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The major strength of our study is the nationwide design.

Linking patient contacts in the data registers through the unique Danish personal identification number is a strength.

The use of consecutive annual data from 2005 to 2016 is also unique.

A limitation of this study is the fact that the Danish healthcare system has a different construct from other countries, using a gatekeeper function with the aim of ensuring that only patients who need more specialised care access secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities.

Since current Danish registration practice precludes identifying patients who were seen only in the emergency department, we chose to include all unplanned hospital contacts.

Introduction

Unplanned admissions take a heavy toll on healthcare systems and remain a major challenge from a cost perspective.1 2 As demand for healthcare increases worldwide, healthcare systems, including in Denmark, are being restructured and reformed to accommodate this demand and to provide continuous high-quality acute-care services.3–6

Previous reviews of international healthcare system reforms have shown that restructuring into acute medical units is associated with lower in-hospital mortality and decreased length of stay; these units do not include care provided for paediatric, psychiatric, surgical or obstetric/gynaecological patients).7 8 As in all other healthcare systems, emergency departments (ED) play an important and prominent role in Denmark as the place where most patients start an unplanned healthcare experience. Due to increased demand and case complexity, structural efforts have been made in Denmark to reduce acute hospitalisations (and to reduce the length of stay and improve patient outcomes for those who do need acute hospitalisation). The Danish healthcare system has been centralised into fewer hospitals and a single-entry point through the ED to the hospital for acute patients.

Nevertheless, few studies have evaluated the effect of this reform over a long period of time.9–13 Moreover, existing studies did not account for changes in the patient population over time or for regional variation.14 Therefore, with this investigation, our aim was to track changes in unplanned acute activity and to identify and characterise patients with unplanned contacts in Danish hospitals from 2005 to 2016.

Materials and methods

Population

This descriptive study, based on Danish nationwide registers, included all unplanned acute hospital contacts (acute inpatient, acute outpatient, ED patient and repeated acute visits by the same person) by adults (aged ≥18 years) with public Danish hospitals from 1 January 2005 through 31 December 2016.15 Private hospitals in Denmark treat fewer than 3% of patients and do not treat acute patients.16 We excluded planned contacts (planned inpatient admissions, outpatient visits) and all patients in labour (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems codes O00-O99, ICD-10).

Setting

Healthcare in Denmark is tax-funded and includes universal coverage of hospital services free of charge to all residents.17 Prescription drugs require some co-payment, and all residents are assigned a general practitioner (GP) who acts as a gatekeeper to secondary healthcare.15 Prior to 2014 access to EDs was on a walk-in basis, but since 1 January 2014 ED visits have required referral from a doctor or activation of the emergency medical services.18

Since 2007, five regional authorities (Capital Region of Denmark, Region Zealand, Region of Southern Denmark, Central Denmark Region and North Denmark Region) are responsible for governing, managing and funding the public hospitals. Prior to that period, 14 counties were responsible for public healthcare.

In all five regions in Denmark, before 1 January 2014, GPs offered out-of-hours primary medical services either as home visits or in centralised clinics.14 By 1 January 2014, the Capital Region of Denmark changed the out-of-hours system so that all clinics were ED-based and staffed, while the other four regions remained unchanged.14

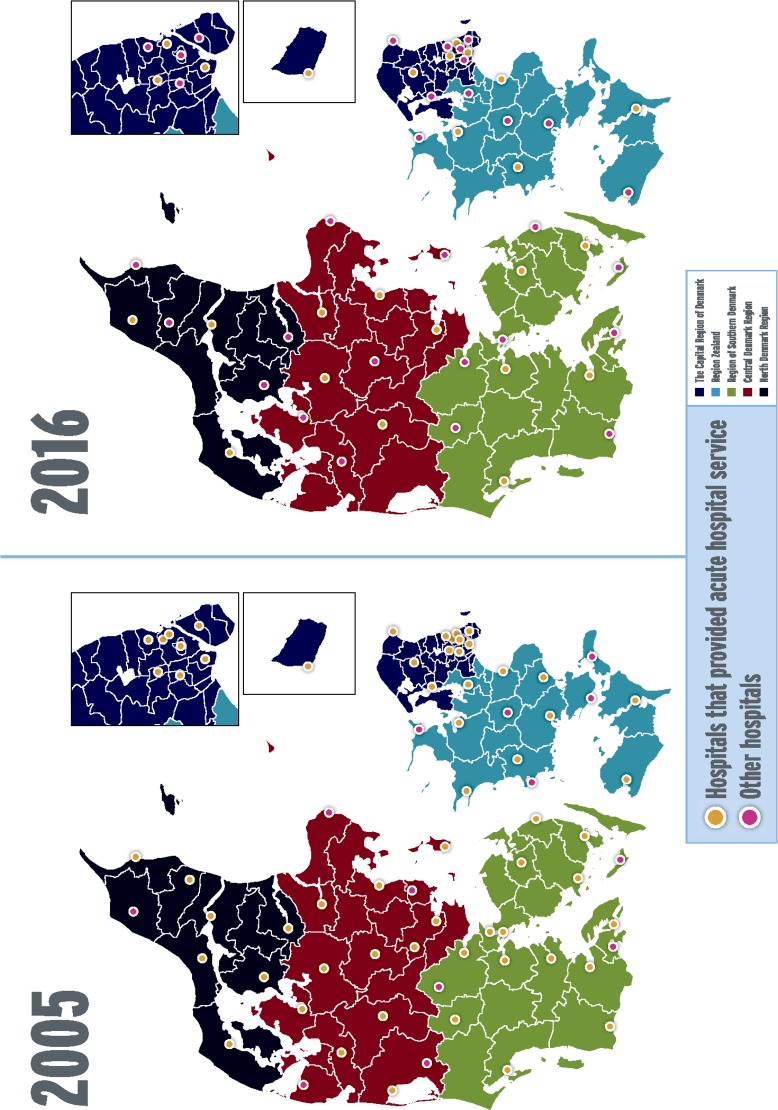

In 2005, approximately 40 hospitals provided acute hospital services (figure 1).1 Several smaller hospitals have closed over the years, further centralising care and increasing patient volume and staff experience (figure 1).19 The new hospital structure dictated a single point of entry for acute patients through the EDs, regardless of the healthcare problem, and the number of hospitals with an ED will be reduced to 21 by 2025.19

Figure 1.

Map of hospitals that provides acute hospital service and other hospitals in 2005 and 2016. Copyright, Research Unit in Emergency Medicine, Hospital of South West Jutland.

Data sources

Our study cohort was based on data from Danish health registries, including the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) and the Danish Civil Registration System.15 20 These registers contain complete data on hospital contacts and demographic data.21 All Danish residents have a unique personal identification number that allows cross linkage of all national registries.21 In addition, we used data on the number of citizens (extracted from Statbank Denmark).22

Variables

Each hospital contact (ie, ED visit, ward admission or transfer between units) is coded as individual contacts in the DNPR, so we merged all consecutive contacts with no more than a 3-hour time difference into one combined contact (online supplementary figure 1).23 Hospitals contacts are identified in DNPR combining the variables, patient contacts and admission type.15

bmjopen-2019-031409supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

We extracted the primary discharge diagnosis from DNPR for all contact and combined them into diagnostic groups based on the individual ICD-10 codes.24 An exception was infectious diseases which we combined with diagnoses of infectious diseases from the remaining organ-specific chapters.12 We also combined diagnoses originating in the perinatal period and congenital malformations (chapters XVI and XVII) into one group (online supplementary table 1).

Age was grouped into four categories: 18–49, 50–64, 65–79 and 80+ years, and we age-adjusted the number of contacts per 1000 citizens as per the population in 2016.25

Comorbidity was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a marker for chronic comorbidity burden.26 This value was calculated based on hospital diagnoses 10 years before the hospital contact. The CCI was coded at three levels: low (score 0), moderate (score 1–2) and high (score ≥3).

Time of arrival was extracted from the DNPR and categorised into weekday (Monday 7:00 to Friday 14:59) and weekend (Friday 3:00 to Monday 6:69).11 Time of day was categorised into three periods: daytime (7:00 to 2:59), evening (3:00 to 22:59) and night (23:00 to 6:59).11

Country of origin was extracted from the Danish Civil Registration System and categorised as Danish, western (Europe, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) but not Danish and non-western.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted for developing patient relevant outcomes or to interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Statistics

We obtained data for entire country and stratified by the five regions (Capital Region of Denmark, Region Zealand, Region of Southern Denmark, Central Denmark Region and North Denmark Region). Demographic characteristics are presented as 1-year prevalence in absolute numbers and proportions (95% CIs). The variables were annual number of contacts, length of stay, number of contacts per 1000 citizen per year, age-adjusted contacts per 1000 citizens per year, sex, age groups, country of origin, CCI, discharge diagnosis and time of arrival. All variables are presented as annual numbers, and they are also described at the regional level (online supplementary tables 2–21). An exception is number of contacts per 1000 citizens per year because of missing data for number of citizens before 2007. Data were analysed using Stata V.15.0 (Stata Corp). We conducted several additional analyses to test the robustness of our findings. For our primary results, we chose a 3-hour cut-off between individual contacts when merging into combined hospital contacts.23 To test this choice, we recoded our data using a 6-hour and 12-hour time limits.23

Our data span all hospital contacts and thus almost all possible diagnoses. We also chose to assess two discharge diagnosis specifically: pneumonia and hip fracture. Our rationale was that patients discharged with these conditions would not have had a significant modification of treatment during our study period. To test this choice, we recoded our data only for patients discharged with pneumonia (ICD-10 diagnoses DJ12–DJ18) or hip fracture (ICD-10 diagnosis DS72).

Ethics

Only aggregated information could be extracted from the research server.27

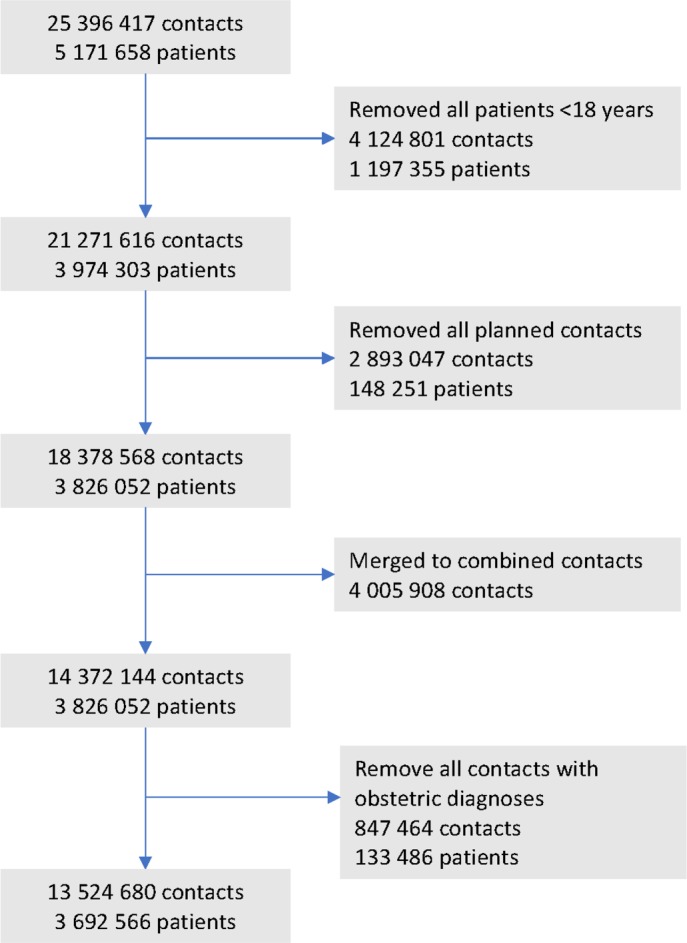

Results

Our study comprised all hospital contacts from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2016. After exclusion of contacts for age under 18 years, planned contacts and obstetric diagnoses, we merged the data from single to combined contacts (see methods) to yield a total of 13 524 680 included contacts (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of study inclusions and exclusions and data preparation.

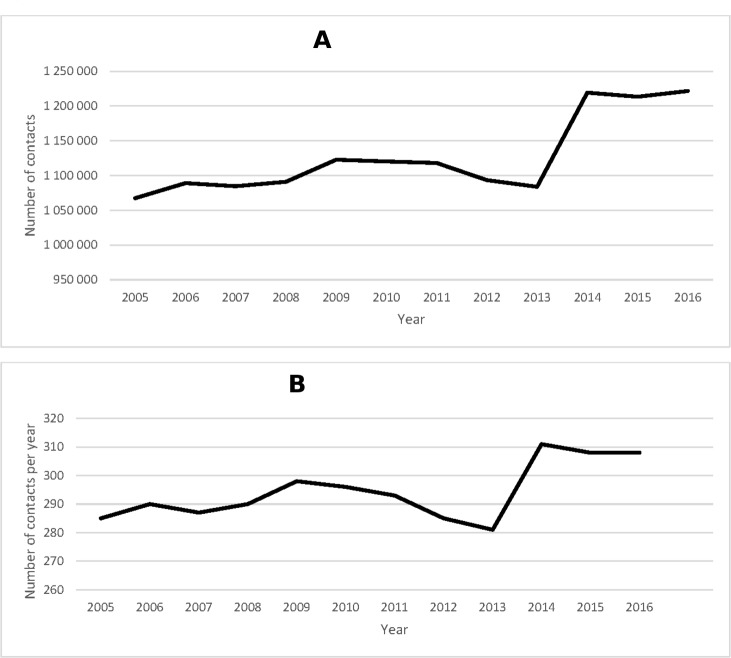

The annual number of acute hospital contacts increased from 1 067 390 in 2005 to 1 221 601 in 2016 (table 1, figure 3A, online supplementary tables 22–25). The biggest increase in the number of contacts occurred from 2013 to 2014, resulting from increases in the Capital Region of Denmark (online supplementary tables 2–3). The number of contacts per 1000 citizens per year increased from 278 visits in 2005 to 308 contacts in 2016. When adjusted for age (distribution per population in 2016), the number of contacts per 1000 citizens per year increased from 2005 to 2016 (table 1, figure 3B, online supplementary file 22–25).

Table 1.

Number of unplanned hospital contacts in Denmark (selected years)

| Year | 2005 | 2013 | 2014 | 2016 | ||||

| Number of contacts | 1 067 390 | 1 083 877 | 1 219 238 | 1 221 601 | ||||

| Length of stay | ||||||||

| ≤24 hours | 691 027 | 64.7 (64.6–64.8) | 707 955 | 65.3 (65.2–65.4) | 834 837 | 68.5 (68.4–68.6) | 847 644 | 69.4 (69.3–69.5) |

| 24 hours | 376 366 | 35.3 (53.2–53.4) | 375 922 | 34.7 (34.6–34.8) | 384 401 | 31.5 (31.4–31.6) | 373 957 | 30.6 (30.5–30.7) |

| Number of contacts per 1000 citizens per year | 278 | 278 | 310 | 308 | ||||

| Age-adjusted number of contacts per 1000 citizens per year | 285 | (284–285) | 281 | (280–282) | 311 | (311–312) | 308 | (308–309) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 563 458 | 52.8 (52.7–52.9) | 555 437 | 51.2 (51.2–51.3) | 607 242 | 49.8 (49.7–49.9) | 608 460 | 49.8 (49.7–49.9) |

| Female | 503 932 | 47.2 (47.1–47.3) | 528 440 | 48.8 (48.7–48.8) | 611 996 | 50.2 (50.1–50.2) | 613 141 | 50.2 (50.1–50.3) |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||||

| 18–49 | 505 310 | 47.3 (47.2–47.4) | 465 361 | 42.9 (42.8–43.0) | 543 367 | 44.6 (44.5–44.7) | 522 082 | 42.7 (42.6–42.8) |

| 50–64 | 225 554 | 21.1 (21.1–21.2) | 222 544 | 20.5 (20.5–20.6) | 247 876 | 20.3 (20.3–20.4) | 253 577 | 20.8 (20.7–20.8) |

| 65–79 | 198 534 | 18.6 (18.5–18.7) | 245 940 | 22.7 (22.6–22.8) | 268 624 | 22.0 (22.0–22.1) | 279 503 | 22.9 (22.8–23.0) |

| 80+ | 137 992 | 12.9 (12.9–13.0) | 150 032 | 13.8 (13.8–13.9) | 159 371 | 13.1 (13.0–13) | 166 439 | 13.6 (13.6–13.7) |

| Country of origin | ||||||||

| Denmark | 979 727 | 92.0 (92.0–92.1) | 974 984 | 90.2 (90.2–90.3) | 1 080 822 | 89.0 (88.9–89.0) | 1 074 158 | 88.2 (88.1–88.2) |

| Western | 27 230 | 2.6 (2.5–2.6) | 35 002 | 3.2 (3.2–3.3) | 41 665 | 3.4 (3.4–3.5) | 43 827 | 3.6 (3.6–3.6) |

| Non-western | 57 650 | 5.4 (5.4–5.5) | 70 343 | 6.5 (6.5–6.6) | 92 504 | 7.6 (7.6–7.7) | 100 297 | 8.2 (8.2–8.3) |

| Time of week | ||||||||

| Weekday | 721 078 | 67.6 (67.5–67.6) | 742 915 | 68.5 (68.8–68.6) | 804 216 | 66.0 (65.9–66.0) | 798 881 | 65.4 (65.3–65.5) |

| Weekend | 346 312 | 32.4 (32.4–32.5) | 340 962 | 31.5 (31.4–31.5) | 415 022 | 34.0 (34.0–34.1) | 422 720 | 34.5 (34.5–34.7) |

| Time of day | ||||||||

| Daytime | 525 786 | 49.3 (49.2–49.4) | 542 338 | 50.0 (49.9–50.1) | 597 307 | 49.0 (48.9–49.1) | 594 784 | 48.7 (48.6–48.68 |

| Evening | 414 091 | 38.8 (38.7–38.9) | 415 564 | 38.3 (38.2–38.4) | 486 028 | 39.9 (39.8–39.9) | 491 873 | 40.3 (40.2–40.4) |

| Night-time | 127 513 | 11.9 (11.9–12.0) | 125 975 | 11.6 (11.6–11.7) | 135 906 | 11.1 (11.1–12.0) | 134 944 | 11.0 (11.0–11.1) |

Figure 3.

(A) Number of unplanned acute contacts in Denmark, 2005–2016. (B) Age-adjusted number of unplanned acute contacts per 1000 citizens per year in Denmark, 2005–2016.

Demographics

The demographics of the unplanned contacts also changed. In 2005, most were men (52.8 %), but the proportion of men was slightly less than 50% in 2016 (table 1, online supplementary tables 22–23). Likewise, in 2005 most contacts were young (47.3% were of age 18–49), but over time the proportion of older contacts increased (online supplementary tables 22–23).

The annual proportion of contacts lasting less than 24 hours increased from 64.7% in 2005 to 69.4% in 2016 (table 1, online supplementary tables 22–23).

Discharge diagnoses

The pattern of discharge diagnoses changed from 2005 to 2016. In 2005, the three most common discharge diagnoses were injury (35.6 %), factors influencing the health status (14.3%) and infections (8.7%). In 2016, injury (27.5%), infections (14.2%) and systemic and abnormal findings (13.5%) were the most common (table 2, online supplementary tables 24–25). In all regions, the most common diagnosis chapter was injury. Most strikingly, the absolute number and proportion of contacts coded with a discharge diagnosis of infection doubled from 2013 to 2014 in the Capital Region of Denmark (online supplementary tables 4–5).

Table 2.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score and discharge diagnosis of unplanned hospital contacts in Denmark (selected years)

| Year | 2005 | 2013 | 2014 | 2016 | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||||||

| Low (0) | 659 156 | 61.8 (61.7–61.8) | 622 421 | 57.4 (57.3–57.5) | 730 651 | 59.9 (59.8–60.0) | 744 209 | 60.9 (60.8–61.0) |

| Medium (1–2) | 278 878 | 26.1 (26.0–26.2) | 297 533 | 27.5 (27.4–27.5) | 324 659 | 26.6 (26.5–26.7) | 326 946 | 26.8 (26.7–26.8) |

| High (>2) | 129 356 | 12.1 (12.1–12.2) | 163 923 | 15.1 (15.1–15.2) | 163 928 | 13.4 (13.4–13.5) | 150 446 | 12.3 (12.3–12.4) |

| Discharge diagnosis | ||||||||

| Infectious diseases | 92 346 | 8.7 (8.6–8.7) | 110 632 | 10.2 (10.2–10.3) | 161 910 | 13.3 (13.2–13.3) | 173 354 | 14.2 (14.1–14.3) |

| Neoplasms | 30 280 | 2.8 (2.8–2.9) | 25 587 | 2.3 (2.3–2.4) | 24 420 | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 21 247 | 1.7 (1.7–1.8) |

| Blood diseases | 10 476 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 10 802 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 10 175 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 8852 | 0.7 (0.7–0.7) |

| Endocrine diseases | 19 176 | 1.8 (1.8–1.8) | 18 570 | 1.7 (1.7–1.7) | 18 901 | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 19 575 | 1.6 (1.6–1.6) |

| Mental diseases | 17 267 | 1.6 (1.6–1.6) | 21 856 | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 22 854 | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 22 233 | 1.8 (1.8–1.8) |

| Diseases of nervous system | 17 414 | 1.6 (1.6–1.7) | 19 905 | 1.8 (1.8–1.9) | 21 589 | 1.8 (1.7–1.8) | 20 142 | 1.6 (1.6–1.7) |

| Diseases of eye | 3067 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | 3353 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | 6994 | 0.6 (0.6–0.6) | 8156 | 0.7 (0.7–0.7) |

| Diseases of ear | 1914 | 0.2 (0.2–0.2) | 2018 | 0.2 (0.2–0.2) | 4092 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | 3767 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 81 754 | 7.7 (7.6–7.7) | 77 239 | 7.1 (7.1–7.2) | 80 062 | 6.6 (6.5–6.6) | 79 735 | 6.5 (6.5–6.6) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 25 676 | 2.4 (2.4–2.4) | 28 884 | 2.7 (2.6–2.7) | 31 676 | 2.6 (2.6–2.6) | 33 410 | 2.7 (2.7–2.8) |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 41 659 | 3.9 (3.9–3.9) | 48 876 | 4.5 (4.5–4.5) | 64 745 | 4.5 (4.5–4.5) | 54 885 | 4.5 (4.5–4.5) |

| Diseases of the skin | 3579 | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | 3817 | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | 5971 | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 5097 | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | 36 006 | 3.4 (3.3–3.4) | 30 382 | 2.8 (2.8–2.8) | 39 233 | 3.2 (3.2–3.2) | 39 580 | 3.2 (3.2–3.3) |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 16 875 | 1.6 (1.6–1.6) | 20 744 | 1.9 (1.9–1.9) | 24 980 | 2.0 (2.0–2.1) | 28 284 | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) |

| Diseases of the perinatal period and congenital malformations | 56 324 | 5.3 (5.2–5.3) | 56 254 | 5.2 (5.1–5.2) | 62 459 | 5.1 (5.1–5.2) | 60 545 | 5.0 (4.9–5.0) |

| System and abnormal findings | 80 671 | 7.6 (7.5–7.6) | 120 068 | 11.1 (11.0–11.1) | 149 807 | 12.3 (12.2–12.3) | 16 494 | 13.5 (13.4–13.5) |

| Injury | 379 518 | 35.6 (35.5–35.6) | 341 767 | 31.5 (31.4–31.6) | 343 728 | 28.2 (28.1–28.3) | 366 268 | 27.5 (27.4–27.6) |

| Factors influencing the health status | 152 681 | 14.3 (14.2–14.4) | 142 717 | 13.2 (13.1–13.2) | 155 649 | 12.8 (12.7–12.8) | 145 972 | 11.9 (11.9–12.0) |

Time of attendance

The proportion of patients arriving during weekdays or weekends varied little during the study period (table 1, online supplementary tables 22–23), with most (72.7%–75.0%) arriving on weekdays, and an almost equal proportion arrived during and outside of office hours (table 1, online supplementary tables 22–23). There were more contacts during the weekends in 2016 than in 2005 (table 1, online supplementary tables 22–23).

Sensitivities analyses

Recoding combined contacts with 3-hour, 6-hour and 12-hour intervals had little effect on the total number of combined contacts (online supplementary figures 2–3).

The proportion of contacts admitted with pneumonia and hip fracture changed over time both nationally and in each of the five regions. The number of contacts with pneumonia increased between 2005 and 2016, whereas the number of contacts with hip fracture decreased (online supplementary table 26).

Discussion

This nationwide descriptive study shows an increasing number of acute hospital contacts over time, especially the number of contacts of female patients increased. We also found that the most common time to visit was during the weekdays, with an almost equal number of visits during and outside of office hours.

Not surprisingly, the number of contacts among the elderly population increased.28 International studies have shown a trend towards an increase in ED visits and an ageing population seeking healthcare almost globally.29–32 An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report from 2011 found that most OECD countries (including Germany, Belgium and UK) had annual increase in the number of ED visits. The number of attendances per 1000 citizens ranged from 70 in the Czech Republic to 705 in Portugal.6 A recent report from UK showed that the number of patients admitted urgently to the hospitals increased with 42% over the last decade while ED contacts increased by 13%.33

We found an unexpected increase in the number of contacts from 2013 to 2014, in absolute numbers and per 1000 citizens per year, both unadjusted and age-adjusted. By 2014, referral from a healthcare professional for all ED contacts was implemented nationally and ED visits on a walk-in basis were abolished. While we expected this change in admission criteria to lead to a reduction in the number of acute patients in the four regions which did not implement that patients previously seen in the GP-staff out-of-hours patient clinics were seen in the EDs, this was not evident in our numbers. Due to the proportion of citizens in the Capital Region of Denmark, the increase in number of contacts in this region alone affected the trend in contacts on a nationwide basis. A previous population study found that the five Danish regions showed homogeneity regarding sociodemographic and health-related characteristics.34 Our findings likely are not the result of difference in the population among the regions but probably are influenced by differences in healthcare among regions following the 2007 reform.

The three most common diagnoses changed over the study period and proportions changed over time. We found that the proportion of infections increased, and almost one-fourth of the contacts received a non-specific diagnosis. A similar pattern has been reported previously for Denmark. A study from the North Denmark Region showed that more than half of the patients had a non-specific or an injury diagnosis.9 However, that study identified a very low proportion of infections in contrast to our findings. One possible explanation for the discrepancy is that we chose to group all infections into one variable (across all ICD-10 chapters) thus had contacts in this category.

Limitation and strengths

The major strength of our study is its nationwide design. We included all patients with an acute hospital contact which minimised the risk of selection bias. In addition, linking patient contacts in the data registers through the unique Danish personal identification number is a strength.

The use of consecutive annual data from 2005 to 2016 is unique. Previous studies have compared data covering 2 years (mostly in a before-and-after design). The use of annual data gave us the opportunity to monitor changes in patient contacts and compare these changes to organisational shifts in the Danish healthcare system, for example, in the gatekeeper function in the Capital Region of Denmark.

We performed several sensitivity analyses and all results confirmed the robustness of our findings.

A limitation of the study is the fact that the Danish healthcare system differs from other countries because of its GPs gatekeeper function which aims to ensure that only patients who need more specialised care gain access to secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities. Thus, our findings might not be generalisable globally.

Since the current Danish registration practice makes it impossible to identify patients who were seen only in the ED, we chose to include all unplanned hospital contacts. As a result, our study cohort is bigger than the population seen only in the ED, making the finding relevant not only for emergency catchment but also systemwide. This factor also implies that any regional differences will affect our data and thus our finding.

Conclusion

This nationwide study describes the changes in acute hospital contacts from 2005 to 2016. During this period, huge investments and healthcare organisational structural changes were made in the five healthcare regions of Denmark. The demographic shifts and the reform in 2007 affected unplanned acute activity differently among the five regions. The Capital Region of Denmark in particular showed an increasing incidence rate of contacts, whereas the four other regions experienced more stable rates.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @BieBogh

Contributors: MF data managed and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. SBB contributed to data management. MBr performed critical appraisal of the manuscript. SBB, DPH, MBe, SPJ and MBr contributed to writing, reviewing and revising the paper. All authors interpreted the data and critically reviewed drafts of the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: MF was supported by the University of Southern Denmark and the Region of Southern Denmark, but these entities were not involved in any aspect of this article and have no influence on the study results or publication and no role in the study design, data collection or analysis.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: In compliance with Danish law, register studies are exempted from gaining approval from an ethics committee; however, we did gain approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency (file no. 17/18411).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Because of Danish law, it is not possible to share data. All data extracted from registers were stored and analysed on a secure research server placed at Statistics Denmark, separated from the production network and accessed via VPN. Statistics Denmark has strict rules against transfer of micro data back to the researcher and removed all potential information that could identify individuals.

References

- 1. SoS-oÆ DR. De danske akutmodtagelser—status 2016 Denmark, 2016. Available: http://www.regioner.dk/media/3084/statusrapport-om-akutmodtagelserne.pdf

- 2. Purdy S, Griffin T, Salisbury C, et al. . Ambulatory care sensitive conditions: terminology and disease coding need to be more specific to aid policy makers and clinicians. Public Health 2009;123:169–73. 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baier N, Geissler A, Bech M, et al. . Emergency and urgent care systems in Australia, Denmark, England, France, Germany and the Netherlands—analyzing organization, payment and reforms. Health Policy 2019;123:1–10. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. OECD Health Working Papers N, OECD Publishing, Paris Emergency care services: trends, drivers and interventions to manage the demand. Paris: OECD Health Working Papers N, OECD Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Denmark S. Emergency department visits by sex, age, diagnosis, region and time: statistic Denmark, 2019. Available: http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=2560

- 6. Berchet C. Emergency care services. 2015.

- 7. Reid LEM, Dinesen LC, Jones MC, et al. . The effectiveness and variation of acute medical units: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:433–46. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scott I, Vaughan L, Bell D. Effectiveness of acute medical units in hospitals: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:397–407. 10.1093/intqhc/mzp045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Søvsø MB, Hermansen SB, Færk E, et al. . Diagnosis and mortality of emergency department patients in the North Denmark region. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:548 10.1186/s12913-018-3361-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter-Storch R, Olsen UF, Mogensen CB. Admissions to emergency department may be classified into specific complaint categories. Dan Med J 2014;61:A4802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duvald I, Moellekaer A, Boysen MA, et al. . Linking the severity of illness and the weekend effect: a cohort study examining emergency department visits. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2018;26:72 10.1186/s13049-018-0542-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vest-Hansen B, Riis AH, Sørensen HT, et al. . Acute admissions to medical departments in Denmark: diagnoses and patient characteristics. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:639–45. 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Christiansen T, Vrangbæk K. Hospital centralization and performance in Denmark—ten years on. Health Policy 2018;122:321–8. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. SVoSR R. Regionale lægevagter OG Akuttelefonen 1813, en kortlængning Med forkus på organisering, aktivitet OG økonomi. Viven TIL Velfæd: Det Nationale Forsknings- OG Analysecenter for Velfærd, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, et al. . The Danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. TMo H. Healthcare in Denmark—an overview 2017.

- 17. Olejaz M, Juul Nielsen A, Rudkjobing A. Health systems in transition In: Denmark health system review. 14, 2012: 1–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li D. Life in Denmark. Available: https://lifeindenmark.borger.dk/Living-in-Denmark/Emergencies

- 19. Sundhedsstyrelsen Styrket akutberedskab – planlægningsgrundlag for det regionale sundhedsvæsen. 2007 Denmark, 2007. Available: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2007/~/media/0B0FC17774D74E7FA404D272DA9C9369.ashx

- 20. Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, et al. . Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:12–16. 10.1177/1403494811399956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Statistic Denmark, 2019. Available: http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=2560

- 23. Lassen A, Joergensen HS, Jørsboe HB, et al. . The Danish database for acute and emergency hospital contacts. Clinical epidemiology 2016;8:469–74. 10.2147/CLEP.S99505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sundhedsdatastyrelsen Fællesindhold for basisregistrering AF sygehus-patienter 2018-1 2018.

- 25. Fløjstrup M, Henriksen DP, Brabrand M. An acute hospital admission greatly increases one year mortality—getting sick and ending up in hospital is bad for you: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med 2017;45:5–7. 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Researchers SDf Data for research, 2019. Available: https://www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice

- 28. Statistik D. Markant flere ældre I fremtiden: Danmarks Statistik, 2018. Available: https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/nyt/GetPdf.aspx?cid=26827

- 29. Lin MP, Baker O, Richardson LD, et al. . Trends in emergency department visits and admission rates among US acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1708–10. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Powell MP, Yu X, Isehunwa O, et al. . National trends in hospital emergency department visits among those with and without multiple chronic conditions, 2007–2012. Hosp Top 2018;96:1–8. 10.1080/00185868.2017.1349523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skinner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A. Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006-2011: Statistical Brief #179 : Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) statistical briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, et al. . Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA 2010;304:664–70. 10.1001/jama.2010.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Adam Steventon SD, Friebel R, Gardner T, et al. . Briefing: Emergency hospital admissions in England: which may be avoidable and how?Available: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/Briefing_Emergency%2520admissions_web_final.pdf2018

- 34. Henriksen DP, Rasmussen L, Hansen MR, et al. . Comparison of the five Danish regions regarding demographic characteristics, healthcare utilization, and medication use—a descriptive cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140197 10.1371/journal.pone.0140197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031409supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)