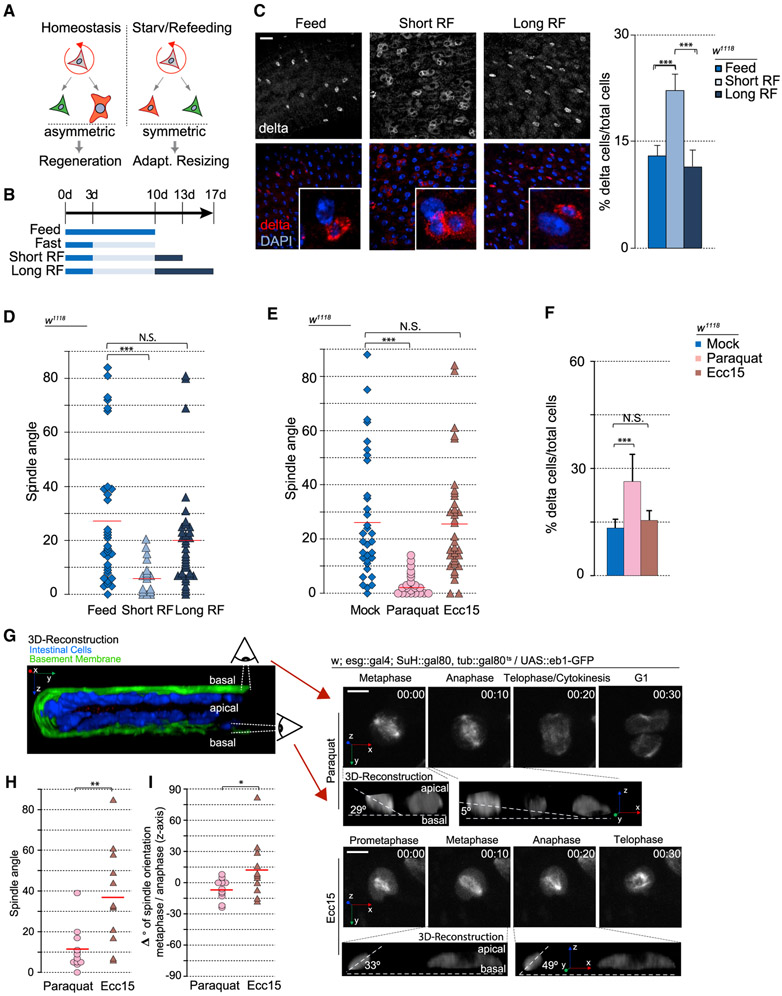

Figure 1. Spindle Orientation Responds to Different Environmental Perturbations.

(A) Diagram representing different modes of ISC division in response to different environmental challenges.

(B) Timeline of fasting and refeeding conditions.

(C) Percentage of D1+ cells (ISCs) increased after short-term refeeding but returned to baseline levels after long-term refeeding. Insets depict a likely clone.

(D and E) Quantification of spindle orientation after refeeding conditions (D) and Paraquat treatment versus Ecc15 infection (E).

(F) Percentage of D1+ cells increased after paraquat treatment, but not after Ecc15 infection.

(G) Intestines imaged live ex vivo (hours:minutes). Insets depict 3D reconstruction.

(H) Spindle orientation in live ISCs mimicked that of fixed cells.

(I) Changes in spindle orientation between metaphase and anaphase.

Mean ± SD (C and F); n = 9 flies (C and F) and n = 11 cells from 6 flies (H and I), with spindle orientation quantified from 15–30 flies (D and E); N.S., not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, based on a Kruskal-Wallis test (C–F) or Mann-Whitney test (H and I). Red bar, mean (D, E, H, and I). Scale bars, 20 μm (C) and 5 μm (G).