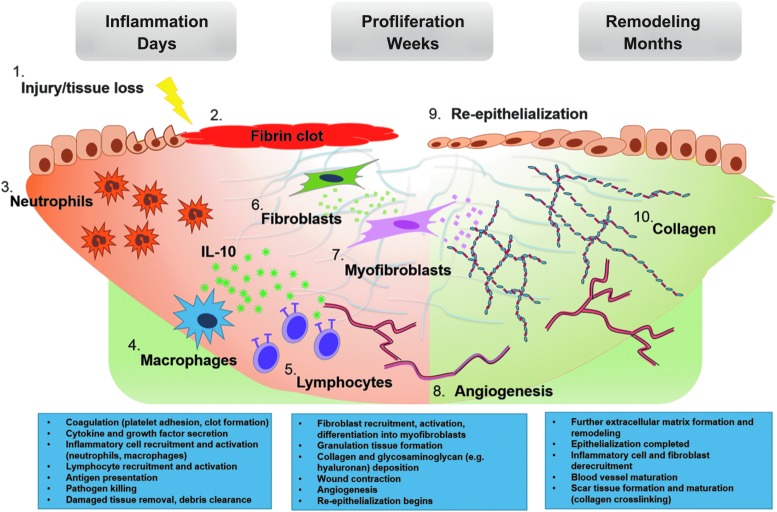

Figure 1.

Wound healing and fibrogenesis. Wound healing progresses in a well-defined series of steps. After tissue injury (1) coagulation begins, ultimately resulting in the formation of a fibrin clot (2). Damaged tissue or detected pathogens spur the release of local cytokine and growth factor release, beginning the inflammatory phase of wound healing. These “danger signals” result in the recruitment of local and circulating innate immune cells, neutrophils (3) and macrophages (4) being predominant initially. These phagocytes begin antigen presentation and thereby recruit and activate effector cells of the adaptive immune system (5). IL-10 is broadly expressed by immune cells, but the predominant cellular sources are macrophages and T cell subsets (i.e., T helper 2 and regulatory T cells).101,102 Pathogen and damaged tissue clearance is the ultimate result of the inflammatory phase, staging the wound bed for regrowth. The proliferative phase is characterized by the activities of the fibroblast (6), which secretes the ECM components that provide the scaffolding for regenerated tissue. Granulation tissue, composed of immature blood vessels (8) and loose connective tissue fibers, begins to fill the wound, providing a structure within which fibroblasts can act and upon which epithelial cells migrate (9). Fibroblasts are induced by various cytokines and growth factors to differentiate into myofibroblasts (7), strengthening the wound by depositing collagen fibers, glycosaminoglycans, and other structural macromolecules. The myofibroblast phenotype is also contractile, acting to hasten wound closure. At this point, the remodeling phase begins, as newly created structures undergo maturation and strengthening or are pruned away. This stage can last from months to years. The initially deposited collagen III is replaced by collagen I, and collagen bundling and crosslinking (10) serves to further increase the tensile strength of the wound, while also resulting in what we recognize as scar tissue formation. Inflammatory cells and fibroblasts are no longer recruited, and many of those present in the wound bed undergo apoptosis. This gradual quiescence concludes the wound healing process and prevents the continued production of scar tissue, which could lead to tissue dysfunction. ECM, extracellular matrix; IL-10, interleukin-10.