Abstract

Synchrotron X-ray single crystal structure determination of two 2D Hofmann-related compounds, [Ni(p-Xylyenediamine)n-tetracyanonickelate] (abbreviated as Ni-pXdam) and [Ni(tetrafluoro-p-Xylyenediamine)n-tetracyanonickelate] (abbreviated as Ni-pXdamF4), have been conducted. Both the pXdam and pXdamF4 ligands contain two short chains of -CH2NH2 at the para-positions of a phenyl ring. These flexible chains link the 6-fold coordinated Ni2 sites throughout the network. In Ni-pXdam, the closed-2D network of [Ni-(CN-Ni1/4-)4]∞ is broken into 1D chains, leaving the C≡N groups at the trans-positions of the Ni(CN)4 moiety unbridged. The resulting 1D chains [(trans-)-NC-Ni(CN)2-CN-Ni-]∞ runs along the [010] direction of the unit cell. The pXdam ligands bridge in pair between the Ni atoms of the adjacent chains. The catenation structure of [Ni{(pXdam)}]∞ could be referred to as double −1D. In Ni-pXdamF4, the −CH2NH2 ligands connect the neighboring chains via the 6-fold Ni2 site. Surrounding the 4-fold Ni1 site, the two trans terminal C≡N groups were replaced by the Lewis base NH3 during the synthesis process, therefore preventing the propagation of the 2D net to form a 3D network. Computed pore volume of both compounds indicated that there is not sufficient space in the structure to accommodate gas molecules. In both compounds, hydrogen bonds were found, and solvent of crystallization was absent due to the limited free space in the structure.

Keywords: CO2 mitigation, Synthesis, Synchrotron X-ray, 2D Hofmann-related structures, [Ni(p-xylyenediamine)nNi(CN)4], [Ni(tetra-fluoro- p-xylyenediamine)nNi(CN)4]

1. Introduction

The development of a sustainable environment is an urgent need in recent years due to the continual rise in anthropogenic CO2 concentration since the dawn of industrial revolution [1-3]. Gas storage in porous solids has been shown to be technically feasible, and development of novel solid sorbent materials could provide an economical way to capture CO2. Metal organic frameworks (MOFs or coordination polymers) which consist of metal centers and/or metal clusters connected by organic linkers, form porous structures with 1D, 2D, or 3D channel systems [3-50]. By controlling the structure of these materials one can predesign their pore sizes.

For a variety of different applications, chemical architecture using cyanometalates as the main building blocks have been attempted using complementary bridging or chelating ligands. Among them, the Hofmann-diam-type series [Cd(diam)N-(CN)4]•xG (x = 0.5–2,G = aromatic guest) have the 3D metal complex host structure with similar topology, in spite of the variation in the number of methylene units ‘n’ in NH2(CH2)nNH2 (from n = 2 to 9) [51-62]. The cyanometalates often involved octahedral Ni or Cd, square-planar Ni(CN)4, tetrahedral Cd(CN)4, linear Ag(CN)2, and Ag2(CN)3 [51-65]. While most bridging ligands have the properties of being rigid, p-Xylyenediamine (abbreviated as pXdam) and p-tetrafluoroxylyenediamine (abbreviated as pXdamF4) (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2) have shown partial flexibility at the −CH2−NH2−M (M = Ni, Cd, etc) joint [51]. Yuge et al. [51] found that configuration about the C-N bond in the −CH2−NH2−M moieties in combination with the rigid Ni(CN)4 moiety and with different aromatic guests give rise to a variety of geometries, including both 2D and 3D configurations [51].

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the pXdam ligand.

Fig. 2.

Schematic drawing of the pXdamF4 ligand.

The goal of this paper is to utilize the flexibility of the pXdam and the pXdamF4 ligands, in combination with rigid Ni(CN)4 moieties to build a Hofmann type structure. As the F atoms in the phenyl ring of the Ni-pXdamF4 ligands are much larger in size as compare to that of the corresponding H atoms in Ni-pXdam, it would be instructional to investigate the influence of the substituted F's on structure and bonding characteristics of these flexible compounds. Another goal of the study is to determine the role of NH3 which was intended as a blocking ligand during the crystallization process.

2. Experimental

The details of crystal growth of both compounds have been reported in the review paper describing a large family of Pillard Cyanonickelates (PICNICs) [41]. A brief procedure for synthesis, structure characterization using synchrotron radiation at the University of Chicago ChemMatCar/Microdiffraction station of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) of the Argonne National Laboratory, and the computation technique to estimate pore size is summarized below.1

2.1. Synthesis

A technique that we have found to be versatile for crystallization of Ni(L)[Ni(CN)4] compounds is a modified procedure originally used by Cernak et al. to prepare crystalline 1D [Ni(CN)4] containing chain compounds [48]. The approach involves the use of NH3 as a blocking ligand. If the reaction mixture is contained in an open flask, the NH3 will outgas from the solution. Once the concentration of NH3 drops below a threshold level, assembly of the Ni(L) [Ni(CN)4] material will commence. A H2O/DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) mixture as the solvent and a reaction temperature of ~90 °C provided the necessary combination of NH3 out gassing rate and oligomer solubility to produce the targeted polymeric structure. A good crop of crystals are typically obtained in 24 h—48 h. The technique has been found to be adaptable to various organic bridging ligands (L) and has provided a number of crystalline samples that are currently under analysis in our laboratory.

2.2. Synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments

Both small crystals that we used (0.070 × 0.060 × 0.020 mm3 for Ni-pXdam and 0.060 × 0.035 × 0.010 mm3 for Ni-pXdamF4) have a thin-plate morphology. The crystals were mounted on the tip of a glass fiber with paratone oil and cooled down to 100 K with an Oxford Cryojet. X-ray diffraction experiments were performed with a Bruker D8 diffractometer in the vertical mount with a APEX II CCD detector using double crystals technique with Si (111) monochromator at 30 keV (λ = 0.41328 Å for pXdam and 0.49594 Å for PXdam-F4) at sector15 (ChemMatCARS), Advanced Photon Sources (APS). The two structures were studied at different periods of time, which account for the two different wavelengths used. Data were processed with the APEX2 suite software [66] for data reduction and cell refinements. The structures were solved by the direct method and refined on F2 (SHELXTL) [67]. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters, and hydrogen atoms on carbons were placed in idealized positions.

2.3. Computational surface characterization

Computational methods were used to characterize the pore volume and surface area, to estimate the pore size distribution (PSD), and to obtain a visualization of the maximum space available for the uptake of CO2 in the pore. The geometrical techniques chosen have already been described in detail elsewhere [26,28,46].

In brief, the chosen technique for computing the PSD was the method of Gelb and Gubbins [68], in which the local pore size at any given location in the material is equal to the diameter of the largest sphere that contains that point without overlapping the material framework. The value of the PSD at a particular pore diameter is the fraction of the free volume with local pore size equal to that diameter. We first reconstructed the Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4 frameworks from the crystal structure data, identified the coordinates of each atom in the framework, followed by drawing a van der Waals exclusion sphere around each atom (van der Waals radii used were 1.63 Å for Ni, 1.20 Å for H, 1.70 Å for C, and 1.55 Å for N) [69,70]. The PSD was then numerically calculated via the voxel technique described by Palmer et al. [71] using cubic voxels with side length 0.1 Å or smaller. The PSD analysis was repeated using 10 unique realizations of the voxel grid and a final average PSD was computed from the ensemble of randomly generated structures. Uncertainty in the PSD was estimated using jackknife analysis.

The pore volume and surface area were characterized by the accessible volume and accessible surface area metrics, as described by Duren and coworkers [72,73]. The framework atoms were assigned the radii listed above and N2 with assigned diameter of 3.681 Å was used as the probe gas.

3. Results and discussion

Results of structure solution, structure refinements, and crystallographic data for both Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4 compounds are given in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 list the selected bond distances for the Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4, respectively. The atomic positional and displacement parameters, bond angles, and atomic coordinates for the hydrogen atoms of both compounds are reported in supplementary Tables S1 to S4, and S5 to S8, respectively. In the following, the structure of both Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4 are discussed separately, followed by a comparison of the structure of these two compounds.

Table 1:

Refinement parameters and Crystallographic data for Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4.

| Identification code | pXdam | pXdamF4 |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C10 H12 N4 Ni | C6 H7 F2 N4 Ni |

| Formula weight | 246.93 | 223.82 |

| Temperature | 100(2) K | 100(2) K |

| Wavelength | 0.41328 Å | 0.49594 Å |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | C 2/c | P–1 |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 15.2713(12) Å b = 10.1365(7) Å c = 13.4274(9) Å β = 92.003(2)° |

a = 7.4331(16) Å b = 8.1649(17) Å c = 8.3224(18) Å α = 90.277(4) β = 111.525(4) γ = 111.586(4) |

| Volume | 2077.3(3) Å3 | 431.2(2) Å3 |

| Z | 8 | 2 |

| Density (calculated) | 1.579 Mg/m3 | 1.724 Mg/m3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.420 mm-1 | 0.775 mm-1 |

| F(000) | 1024 | 220.0 |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.070 × 0.060 × 0.020 | 0.060 × 0.035 × 0.010 |

| Theta range for data collection | 1.642 to 14.355 | 1.860 to 17.861. |

| Index ranges | −18 ≤ h<=14 −8 ≤ k<=12 −15 ≤ l<=16 |

−9 ≤ h<=6 −9 ≤ k<=10, −10 ≤ l<=10 |

| Reflections collected | 4911 | 5105 |

| Independent reflections | 1725 [R(int) = 0.0405] | 1592 [R(int) = 0.0414] |

| Completeness to theta = 14.357° | 92.0% | 93.9% |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix LSQ on F2 | Full-matrix LSQ on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 1725/0/139 | 1592/0/121 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.130 | 1.068 |

| Final R indices [I > 2sigma(I)] | R1 = 0.0404, wR2 = 0.1171 |

R1 = 0.0632, wR2 = 0.1593 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0539, wR2 = 0.1286 |

R1 = 0.0772, wR2 = 0.1660 |

| Extinction coefficient | n/a | n/a |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.727 and −0.969 e.Å-3 | 1.911 and −0.800 e.Å-3 |

Table 2:

Selected bond distances (Å) in Ni-pXdam.

| Atom-Atom | Bond distance (Å) |

|---|---|

| Ni(1)-C(9) | 1.853(5) |

| Ni(1)-C(11) | 1.861(5) |

| Ni(1)-C(10)#1 | 1.889(4) |

| Ni(1)-C(10) | 1.889(4) |

| Ni(2)-N(3) | 2.048(4) |

| Ni(2)-N(5)#2 | 2.057(4) |

| Ni(2)-N(1) | 2.147(3) |

| Ni(2)-N(t)#1 | 2.147(3) |

| Ni(2)-N(2)#3 | 2.156(3) |

| Ni(2)-N(2)#4 | 2.156(3) |

| N(1)-C(1) | 1.474(3) |

| N(2)-C(8) | 1.473(4) |

| N(3)-C(9) | 1.155(7) |

| N(4)-C(10) | 1.140(5) |

| N(5)-C(11) | 1.162(8) |

| C(1)-C(2) | 1.512(4) |

| C(2)-C(3) | 1.393(4) |

| C(2)-C(7) | 1.394(4) |

| C(3)-C(4) | 1.390(4) |

| C(4)-C(5) | 1.396(4) |

| C(5)-C(6) | 1.387(4) |

| C(5)-C(8) | 1.515(4) |

| C(6)-C(7) | 1.387(4) |

Table 3:

Selected bond lengths (Å) in pXdamF4.

| Atom-Atom | Bond distance (Å) |

|---|---|

| Ni(1)-C(1) | 1.854(7) |

| Ni(1)-C(1)#1 | 1.854(7) |

| Ni(1)-C(7)#1 | 1.880(8) |

| Ni(1)-C(7) | 1.880(8) |

| Ni(2)-N(1)#2 | 2.066(7) |

| Ni(2)-N(1) | 2.066(7) |

| Ni(2)-N(2) | 2.095(5) |

| Ni(2)-N(2)#2 | 2.095(5) |

| Ni(2)-N(4) | 2.138(6) |

| Ni(2)-N(4)#2 | 2.138(6) |

| F(1)-C(5) | 1.357(8) |

| F(2)-C(6) | 1.346(9) |

| N(1)-C(1) | 1.146(10) |

| N(3)-C(7) | 1.137(11) |

| N(4)-C(3) | 1.460(9) |

| C(3)-C(4) | 1.509(10) |

| C(4)-C(5)#3 | 1.370(11) |

| C(4)-C(6) | 1.391(10) |

| C(5)-C(4)#3 | 1.369(11) |

| C(5)-C(6) | 1.373(10) |

3.1. [Ni(p-xylyenediamine)n-tetracyanonickelate] (Ni-pXdam)

The basic motif of Ni-pXdam is shown in Fig. 3. The atomic labelling scheme is shown in Fig. S1 [51]. The chemical formula of the compound was found to be C10H12N4Ni. The structure of Ni-pXdam is monoclinic with space group C2/c, unit cell dimensions were determined to be a = 15.2713(12) Å, b = 10.1365(7) Å, c = 13.4274(9) Å, β = 92.003(2)°, V = 2077.3(3) Å3 and Z = 8.

Fig. 3.

A motif of the Ni(pXdam)[Ni(CN)4] molecules, with partial labeling scheme provided Ni-green, N-blue, C-dark grey, H-light grey. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

As described earlier, despite the rigidity of the central phenyl ring in Ni-pXdam, partial flexibility is allowed for the-CH2-NH2 substituents at para-positions which are favorable for bridging between networks. There are two independent Ni's (Ni1 and Ni2) in the Ni-pXdam structure, as shown in Fig. 3. Ni1 is coordinated to four CN ligands and Ni2 is octahedrally coordinated to N sites. The rigid Ni(CN)4 groups and the pXdam skeletons dominate the structure, including the linear trans-1D chains, [(trans-)-NC-Ni(CN)2-CN-Ni-]∞, running along the [010] direction of the unit cell (Fig. 4). Similar to the structure of [Cd(p-xda)2Ni(CN)4]·m-CH3C6H4NH2 [65], the close-2D network of [Ni-(CN-Ni1/4-)4]∞ in NipXdam is broken into 1D chains, leaving the C≡N groups at the trans-positions of the Ni(CN)4 moiety unbridged [65]. The pXdam ligands bridge in pair between the Ni atoms of the adjacent trans-1D chains. The catenated structure of [Ni{(pXdam)}]∞ could be referred to as double −1D. The pXdam ligands are double ligated at the Ni2 sites: one NH2 group ligates from the apical direction and another one from the equatorial direction. The Ni-NH2-CH2 angles are distorted for both the equatorial and the apical directions (118.6(2)° and 123.9(2)°, respectively). Ni1 exhibits slightly deformed square-planar coordination and the bond distances and angles in the [Ni(CN)4]2− anion, agree with those found in other tetracyano-nicolate (II) complexes [48] (Table 2 and Table S2). The C10-N4 groups, however, form terminal C≡N groups, therefore preventing the propagation of the chains to form a 3D structure. The 2D network is connected to each other via weak intermolecular forces.

Fig. 4.

A view of the Ni-pXdam structure along the b-axis. The pXdam ligands bridge in pair between the Ni atoms of the adjacent trans-1D chain.

The Ni-N and Ni-C bond distances of Ni-N are within the expected range. The mean Ni-C (1.873 Å), Ni-N (2.119 Å), and C≡N (1.152 Å) bond lengths agree with the values reported for other tetracyanonickelate salts [48]. The Ni-N distances (range from 2.048(2) Å to 2.156 (3) Å) are substantially longer than the Ni-C distances (1.853(5) Å to 1.889(4) Å), which also conform to the literature values [49]. The 6-fold Ni-sites are of high spin configuration because nitrogen is acting as a weak-field ligand. As the 4-fold Ni only has 4-coordination (similar to that in Ni(CN)2 [50]), the low-spin square-planar coordination of Ni2+ ions results in a contraction.

There is not sufficient space inside the structure of Ni-pXdam to accommodate any guest molecules. Pore size calculations [68] showed that the congested crystal structure has zero pore volume available to a helium gas probe (diameter 2.28 Å) and zero surface area accessible to a nitrogen gas probe (diameter 3.681 Å). All pores have radius smaller than 1.15 Å, with prominent distributions near 0.45 Å and 1.10 Å. But these pores are not accessible. Also, no entrapped molecules such as the solvents of crystallization (DMSO) was found in the structure.

Another structure feature is the presence of hydrogen bonds between the unbridged CN moiety in the trans-1D Ni(CN)4 and the NH2 groups of the pXdam ligand, namely, N(4) … H(1B) of 2.35 Å, and N(4) … H(2A) of 2.27 Å. These hydrogen bonds also further stabilize the structure. Table S9 gives several hydrogen bonding distances found in Ni-pXdam. As for possible π-π-interactions are concerned, no direct stacking (similar to the stacking mode in graphite) between the aromatic rings of pXdam within bonding distances was observed. The interplanar distances of these rings are about 4 Å, which are greater than the van der Waals contact. Fig. 5 gives the view of the structure along the a-axis.

Fig. 5.

A view of the Ni-pXdam structure along the a-axis, featuring the linear 1D-chain along the b-direciton and the zig-zag layers of the structure running parallel to the c-direciton. In the double ligation of the pXdam ligands at the Ni2 sites, one NH2 ligates from the apical direction and the other from the equatorial direction.

3.2. [Ni(p-tetrafluoroxylyenediamine)n-tetracyanonickelate] (Ni-pXdamF4)

The structure of Ni-PXdamF4 is significantly different from that of monoclinic Ni-pXdam. Ni-pXdam-F4 is triclinic with a space group P-1, a = 7.4331 Å, b = 8.1649 Å, c = 8.3224 Å, α = 90.277°, β = 111.525°, γ = 111.586°, and V = 431.17 Å3. The expected chemical formula is NiC6H7F2N4. The atomic labelling scheme is shown in Fig. S2. The basic motif of Ni-pXdamF4 (Fig. 6) contains two independent Ni's, a rigid phenyl ring, and two flexible −CH2NH2 chains in the para-positions of the phenyl ring. The remaining sites on the phenyl ring are occupied by four fluorine atoms.

Fig. 6.

A motif of the Ni(pXdamF4)[Ni(CN)4] molecules, with partial labeling scheme provided Ni-green, N-blue, C-dark grey, F-yellow, H-light grey. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Similar to the Ni-pXdam structure, Ni-pXdamF4 also forms a 2D structure. As shown in Fig. 6, the Ni1 site is 4-fold coordinated to four approximately coplanar CN groups. Two C1-N1 groups form zig zag chains (C1-N1-Ni2 of 164.9(6)°and N1-C1-Ni1 of 177.2(6)°) and the other two C7-N3 groups were retained as the coplanar terminal C≡N ligands (1.1415 (11) Å). Bonding to the 6-fold Ni2 site are two N1 sites (form the zig-zag chain), two N4 sites (part of the flexible pXdam chain), and two axial N2 sites (from two unexpected terminal NH3 groups instead of a zig-zag chain). Because of the termination of the network bridging by the C≡N groups on the Ni1 site and the terminal NH3 groups on the Ni2 site, a 3D Hofmann-type structure is not achieved.

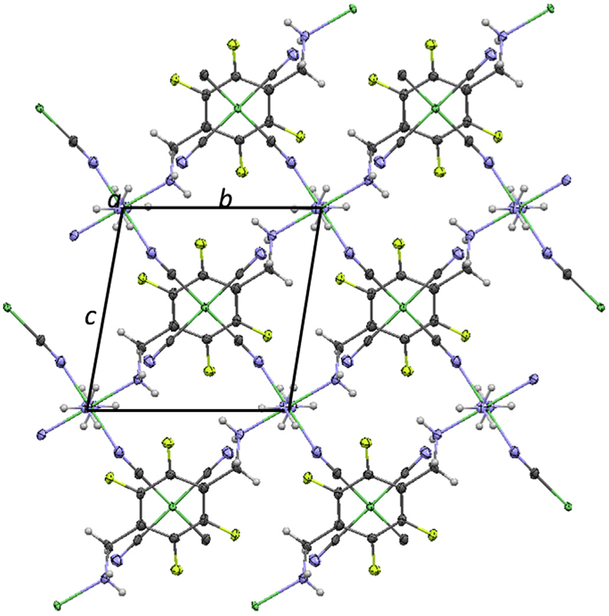

Unlike the structure of Ni-pXdam, the presence of the bulky tetrafluorophenyl ligands prevent the formation of parallel double 1D structure. The −CH2NH2 chain coordinates to the Ni2 site of the neighboring chain instead. Fig. 7 gives a view of the structure along the a-axis, showing linear chains running along the [011] direction. The aromatic rings that contain the F-groups appear to be parallel with the Ni(CN)4 groups. Fig. 8 gives a view of the structure along the b-axis. The overall structure consists of sheets of 2D Ni(CN)4 chains connected by the pXdamF4 groups.

Fig. 7.

A view of the Ni-pXdamF4 structure along the a-direction, showing the parallel sig-zag Ni-CN- Ni-NC- chanins along the [011] directions. In addition, the phenyl rings appear to be parallel to the Ni(CN)4 groups. Ni-green, N-blue, C-dark grey, F-yellow, H-light grey. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 8.

A view of the Ni-pXdamF4 structure along the b-direction. Ni-green, N-blue, C-dark grey, F-yellow, H-light Grey. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The Ni-N and Ni-C bond distances are all within the expected range (Table 3). Ni1 has a square planar arrangement, and the mean Ni-C (1.860 Å) and C≡N (1.153 Å) bond lengths agree with the values reported for other tetracyanonickelate salts [48]. The Ni-N distances (range from 2.066(7) Å to 2.095 (5) Å) are substantially longer than the Ni-C distances (1.880(8) Å to 1.857(4) Å).

The 2D sheets interact with each other via weak intermolecular forces. There are also hydrogen bonds between theses sheets. The unbridged CN terminal groups in one 2D sheet forms hydrogen bonds to the NH2 group of the side chain of the pXdamF4 ligand (N(3)…H(2B) of 2.41 Å, N(3)…H(4A) of 2.25 Å), and to the F atoms. These hydrogen bonds also further stabilize the structure and likely facilitate the parallel situation of the aromatic rings and the Ni(CN)4 moieties. Table S10 gives the hydrogen bonding distances between various groups.

Similar to Ni-pXdam, the computational pore metrics confirm that Ni-PXdamF4 only has negligible space available for gas molecules. Ni-pXdamF4 has zero pore volume available to a helium gas probe and zero surface area accessible to a nitrogen gas probe. The PSD calculations showed that all pores are of radius smaller than 0.90 Å, with a broad band of pores between 0.30 Å and 0.80 Å with similar frequency, but no prominent peaks were found.

3.3. A comparison of the structure of Ni-PXdam and Ni-PXdam-F4

While there are similarities between the Ni-pXdam and the Ni-pXdamF4 structures, such as both are Hoffmann-related structure, both belong to the 2D infinite layered type structure with propagating linear chains, and with the Ni2 sites serving as connectors between the linear chains, there are also significant differences. It is possible that the four electronegative fluorine groups withdraw electrons from the Ni2 site via the phenyl ring and the ─CH2NH2─ chain of the pXdamF4 ligand. The result is that the Ni2 site instead of bonding to the N≡C bond of the Ni1(CN)4 group, it is bonded to NH3, a strong Lewis base.

Because of the presence of the NH3 groups and F-groups in pXdamF4, the structure is different from that of the Ni-pXdam. Instead of having a monoclinic (C2/c) symmetry as that in Ni-pXdam, Ni-pXdamF4 is triclinic (P-1). Furthermore, in Ni-pXdam, one observes the parallel double 1D type structure. In Ni-pXdamF4, double parallel 1D structure is absence because further bending of the ligand would require a substantial amount of energy due to the bulky F groups. In Ni-pXdamF4, the aromatic rings appear to be parallel to the Ni(CN)4 groups (Fig. 8). This parallel situation may be the results of extra weak hydrogen bonding (Table S10).

In both compounds, there is no available space inside the structure for guest molecules. Using a helium probe the gas-accessible porosity is essentially zero. Ni-pXdam has pores at radii 0.5 Å and 1.15 Å. Ni-pXdamF4 has a cluster of pores at radii 0.35 Å to 0.8 Å. In both cases, the small pores are not accessible.

4. Conclusion

Crystal structures of two 2D Hofmann related compounds, Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4, were determined and compared. Their structures are totally different due to the presence of the much larger F atoms in the phenyl rings of Ni-pXdamF4 as compare to the H atoms in the phenyl rings of Ni-pXdam.

Based on a number of Hofmann 3D structures that we have determined in our laboratory and those reported in literature, we expected the possible formation of 3D structures of the Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4 crystals. However, in this work, we observed only 2D structure as a result of the termination of chain bridging in both compounds. In the Ni-pXdam structure, the termination was a result of the retention of terminal C≡N groups. In the Ni-pXdamF4 case, the termination was partly a result of the bonding of Ni to a strong Lewis base NH3 instead of to the NC moiety of the Ni(CN)4 groups. These 2D networks are further stabilized by weak intermolecular forces as well as hydrogen bonding.

The fact that the sorption experiments on the powder form of Ni-pXdam (which was prepared under different conditions), demonstrated possible CO2 capture [41], therefore formation of single crystals of 3D Ni-pXdam is within reach. It is possible that modification of the crystallization conditions, including adjusting the concentration of the NH3 gas as blocking agent, one can obtain single crystals of both Ni-pXdam and Ni-pXdamF4 with 3D Hofmann type structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This technical effort was performed in support of the National Energy Technology's ongoing research in CO2 capture under the RES contract DE-FE0004000. The authors gratefully acknowledge ChemMatCARS Sector 15 which is principally supported by the National Science Foundation/Department of Energy under grant number NSF/CHE-0822838. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

X-ray crystallographic data (Electronic materials as Figure S1, Figure S2, and Table S1 to Table S10).

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2018.04.009.

The purpose of identifying the equipment and computer software in this article is to specify the experimental procedure. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

References

- [1].Gammon RH, Sundquist ET, Fraser PJ, in: Trabalka JR (Ed.), Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide and the Global Carbon Cycle; DOE/ER-239, U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, DC.,USA, 1985, pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Espinal L, Poster DL, Wong-Ng W, Allen AJ, Green ML, Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (2009) 11960–11975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Etheridge DM, Steele LP, Langenfelds RL, Francey RJ, Barnola JM, Morgan VI, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 101 (1996) 4115–4128. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhou HC, Kitagawa S, Chem. Soc. Rev 43 (2014) 5415–5418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dey C, Kundu T, Biswal BP, Mallick A, Banerjee R, Acta Crystallogr. B7 (2014) 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Furukawa H, Cordova KE, O'Keeffe M, Yaghi OM, Science 341 (2013) 1230444-1–1230444-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu Y, Wang ZU, Zhou H-C, Greenh. Gas Sci. Technol. 2 (2012) 239–259. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yaghi OM, Li Q, MRS Bull. 34 (2009) 682–690. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morris RE, Wheatley PS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 47 (2008) 4966–4981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rowsell JLC, Yaghi OM, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 73 (2004) 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen R, Yao J, Gu Q, Smeets S, Barlocher C, Gu H, Zhu D, Morris W, Yaghi OM, Wang HA, Chem. Commun 49 (2013) 9500–9502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang QM, Shen D, Bülow M, Lau ML, Deng S, Fitch FR, Lemcoff NO, Semanscin J, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 55 (2002) 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Britt D, Furukawa H, Wang B, Glover TG, Yaghi OM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am 106 (49) (2009) 20637–20640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Furukawa H, Cordova KE, O'Keeffe M, Yaghi OM, Science 341 (2013), 1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gao W-Y, Chrzanowski M, Ma S, Chem. Soc. Rev 43 (2014) 5841–5866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li B, Zhang Y, Ma D, Ma T, Shi Z, Ma S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 1202–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Meng L, Cheng Q, Kim C, Gao W-Y, Wojtas L, Cheng Y-S, Zaworotko MJ, Zhang XP, Ma S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 51 (2012) 10082–10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tranchemontagne DJ, Hunt JR, Yaghi OM, Tetrahedron 64 (2008) 8553–8557. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Feng D, Gu Z-Y, Chen Y-P, Park J, Wei Z, Sun Y, Bosch M, Yuan S, Zhou H-C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 17714–17717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Feng D, Wang K, Su J, Liu T-F, Park J, Wei Z, Bosch M, Yakovenko A, Zou X, Zhou H-C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 54 (1) (2014) 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Queen WL, Hudson MR, Bloch ED, Mason JA, Gonzalez MI, Lee JS, Gygi D, Howe JD, Lee K, Darwish TA, James M, Peterson VK, Teat SJ, Smit B, Neaton JB, Long JR, Brown CM, Chem. Sci 5 (2014) 4569–4581. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bloch ED, Hudson MR, Mason JA, Queen WL, Zadrozny JM, Chavan S, Bordiga S, Brown CM, Long JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (30) (2014) 10752–10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Caskey SR, Wong-Foy AG, Matzger AJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 130 (2008) 10870–10871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wu H, Simmons JM, Srinivas G, Zhou W, Yildirim T, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 1 (2010) 1946–1951. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chui SS-Y, Lo SM-F, Charmant JPH, Orpen AG, Williams ID, Science 283 (1999) 1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wong-Ng W, Kaduk JA, Siderius DL, Allen AL, Espinal L, Boyerinas BM, Levin I, Suchomel MR, Ilavsky J, Li L, Williamson I, Cockayne E, Wu H, Powder Diffr. 30 (2015) 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bourrelly S, Serre C, Vimont A, Ramsahye NA, Maurin G, Daturi M, Filinehuk Y, Férey G, Llewellyn PL, in: Xu R, Gao Z, Chen J, Yan W (Eds.), A Multidisciplary Zeolites to Porous Materials-the 40th Anniversary of International Zeolite Conference, 2007, pp. 1008–1014. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Espinal L, Wong-Ng W, Kaduk JA, Allen AJ, Snyder CR, Chius C, Siderius DW, Li L, Cockayne E, Espinal AE, Suib SL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 134 (18) (2012) 7944–7951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kauffman KL, Culp JT, Allen AJ, Espinal-Thielen L, Wong-Ng W, Brown TD, Goodman A, Bernardo MP, Pancoast RJ, Chirdon D, Matranga C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50 (2011) 10888–10892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Skoulidas AI, J. Am. Chem. Soc 126 (2004) 1356–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wong-Ng W, Kaduk JA, Espinal L, Suchomel M, Allen AJ, Wu H, Powder Diffr. 26 (2011) 234. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wong-Ng W, Kaduk JA, Wu H, Suchomel M, Powder Diffr. 27 (4) (2012) 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Maji TK, Matsuda R, Kitagawa SA, Nat. Mater 6 (2007) 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zaman MB, Udachin K, Ripmeester JA, Smith MD, zur Loye H-C, Inorg. Chem 44 (14) (2005) 5047–5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hu JS, Shang Y-J, Yao X-Q, Qin L, Li YZ, Guo Z-J, Zheng H-G, Xue Z-L, Cryst. Growth Des 10 (2010) 2676–2684. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Serre C, Science 315 (2007) 1828–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cussen EJ, Claridge JB, Rosseinsky MJ, Kepert CJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 (2002) 9574–9581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wong-Ng W, Culp J, Chen Y, Matranga C, Crystals 6 (9) (2016) 108. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kauffman KL, Culp JT, Allen AJ, Espinal-Thielen L, Wong-Ng W, Brown TD, Goodman A, Bernardo MP, Pancoast RJ, Chirdon D, Matranga C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50 (2011) 10888–10892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hofmann KA, Küspert F, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem 15 (1897) 204. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Culp JT, Madden C, Kauffman K, Shi F, Matranga C, Inorg. Chem 52 (2013) 4205–4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Culp JT, Smith MR, Bittner E, Bockrath B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 130 (2008) 12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Culp JT, Natesakhawat S, Smith MR, Bittner E, Matranga CS, Bockrath B, J. Phys. Chem. C 112 (2008) 7079–7083. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kauffman KL, Culp JT, Goodman A, Matranga C, J. Phys. Chem. C 115 (2011) 1857–1866. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Culp JT, Goodman AL, Chirdon D, Sankar SG, Matranga C, J. Phys. Chem. C 114 (2010) 2184–2191. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wong-Ng W, Culp JT, Chen YS, Zavalij P, Espinal L, Siderius DW, Allen AJ, Scheins S, Matranga CC, Cry. Eng. Comm 15 (2013) 4684–4693. [Google Scholar]

- [47].22 Ćernák J, Abboud KA, Acta Crystallogr. C 56 (2000) 783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ćernák J, Lipkowski J, Monatsh. Chem 130 (1999) 1195. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Küuoçüğlu GS, Yeşilel OZ, Kavlak I, Büyükgüngör O, Struct. Chem 19 (6) (2008) 879. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hibble SJ, Chippindale AM, Pohl AH, Hannon AC, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 46 (2007) 7116–7118 (Bpene 23, 4-coordinate). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yuge H, Asai M, Mamada A, Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem 22 (1995) 71. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hasegawa T, Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom 1 (1984) 365. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom 2 (1984) 341. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hasegawa T, Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom 2 (1984) 351. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hasegawa T, Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, Chem. Lett (1985) 1659. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, Inorg. Chem 25 (1986) 788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hasegawa T, Nishikiori S, Iwamoto T, Chem. Lett (1986) 793. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Iwamoto T, Nishikiori S, Hasegawa T, J. Inclusion Phenom 5 (1987) 225. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hasegawa T, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom 6 (1988) 143. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hasegawa T, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom 6 (1988) 549. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Nishikiori S, Hasegawa T, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem 11 (1991) 137. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hashimoto M, Kitazawa T, Hasegawa T, Iwamoto T, J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem 11 (1991) 153. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Soma T, Yuge H, Iwamoto T, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 33 (1994) 1665. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Soma T, Iwamoto T, Chem. Lett (1994) 821. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Yuge H, Noda Y, Iwamoto T, Inorg. Chem 35 (1996) 1842–1848. [Google Scholar]

- [66].APEX2 (2009.11–0), Program for Bruker CCD X-ray Diffractometer Control, Bruker AXS Inc, Madison, WI, 2009, 67. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Sheldrick GM, SHELXTL, Version 6.14. Program for Solution and Refinement of Crystal Structures, Universität Göttingen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Gelb LD, Gubbins KE, Langmuir 15 (2) (1999) 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bondi A, J. Phys. Chem 68 (3) (1964) 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Rowland RS, Taylor R,J. Phys. Chem 100 (18) (1996) 7384–7391. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Palmer JC, Moore JD, Brennan JK, Gubbings KE, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2 (3) (2011) 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Frost H, Düren T, Snurr RQ,J. Phys. Chem. B 110 (2006) 9565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Düren T, Millange F, Férey G, Walton KS, and Snurr RQ, J. Phys. Chem. C, 111, 15350. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.