Abstract

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a checklist to assess proficient performance of basketball straight speed dribbling skill. The sample was composed of 100 children and adolescents between 7 and 15 years of age with and without structured practice in basketball. The validation process tested the validity domain, decision, tendencies, reliability, responsiveness, and objectivity. The results show that the checklist contains criteria that represent the speed dribbling skill and is sensible to distinguish between different proficiency levels of performance. The results also expressed high reliability and objectivity (intra and inter-rater). In light of the findings, we concluded that the checklist can be used to reliably analyze performance and evaluate the process of learning and development of the straight speed dribbling skill.

Key words: sport skills, measurement, motor performance, team sport games

Introduction

Reliable tools of assessment are crucial for physical educators, sport coaches, and other professionals concerned with improving movement performance. Assessing sport skills allows for grading children with different proficiency levels, predicting future performance and evaluating sports and physical education programs (Currell and Jeukendrup, 2008; Strand and Wilson, 1993; Strumbelj and Erčulj, 2014). Basketball is one of the most played team sports worldwide (International Olympic Committee IOC; Wierike et al. 2015), but, surprisingly, has a limited set of tests available for its practitioners’ evaluation. Game performance depends on a combination of physical, functional, behavioural and specific sport skills (Cousy and Power, 1975; Ferreira and Dante, 2003). Thus, a range of tests are necessary to evaluate players – from children and youth to athletes.

The most used test battery for assessing skills in basketball was proposed by the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD) at the end of the 1980 decade (Strand and Wilson, 1993). In addition to the different basketball skills assessed by the AAHPERD battery (e.g. speed spot shooting, accuracy speed passing, defensive movement), dribbling has been often investigated by different researches, given its importance in the game (Apostolidis and Zacharakis, 2015; Guimarães et al., 2019; Coelho et al., 2008). Dribbling is a technique used to advance in the court (towards the adversary court) possessing the ball by running and repeatedly bouncing the ball on the floor with one hand. When the player wants to move rapidly on the court, with no defender between him and the basket, the speed dribble is used (Lehane, 1981; Summit and Jennings, 1996).

The AAHPERD test that evaluates the dribble in basketball, assesses the time to complete a given course when implementing the speed dribble as quickly as possible. Although it is frequently used, the AAHPERD test just provides information about the product of the movement (movement outcome) (e.g., how fast the outcome was reached). Recent systematic reviews showed that most of the sport tests focus on accuracy, placement, passing, shooting, and time to complete a specific task, i.e., products of the movement (Ali, 2011; Currell and Jeukendrup, 2008; Robertson et al., 2013). Currently, there is no test that evaluates the process of any basketball skill, including dribbling.

Research of different areas of motor behaviour (Logan et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2007; Roberton and Konczak, 2001; Ré et al., 2018; Rudd et al., 2016) has already stressed the importance of assessing both the process and products of the movement. Relying exclusively on one of them may not be sufficient to capture the complexity of motor skills. Information about both the product and the process of the sports skills can fully inform the coaches and teachers about the movement aspects (“components”; e.g., arm motion in dribbling) in which youth athletes are proficient and their relation to the movement outcome (Roberton and Konczak, 2001; Seefeldt, 1980). For instance, a coach equipped with such a measurement tool can recognize that his/her athlete fails to achieve a given outcome (e.g., time to cross the court dribbling) because he/she does not perform a certain part of movement (e.g., movement of pushing the ball) proficiently.

In view of the lack of studies assessing the process of movements in basketball, the present study aimed to develop and validate a checklist for evaluating the straight speed-dribbling skill process. We aimed to develop a test considering all required psychometric properties, such as reliability, validity, feasibility, and responsiveness (Barrow et al., 1989; Mokkink et al., 2012; Robertson et al., 2013). Submitting a test to validation, i.e. certifying its psychometric qualities, is a necessary step to support further use (e.g., one must be aware that the test measures what it intends to) and increases the confidence that professionals have on the test’s results.

Methods

We followed the steps of construction and validation of motor tests suggested by Barrow et al. (1989), Safrit and Wood (1995) and Mokkink et al. (2012). The test was validated in terms of the criteria domain, decision, reliability, responsiveness, as well as intra- and inter-evaluator objectivity.

Participants

Participants of this study were selected from a bigger project that aimed to investigate the changes in fundamental movement skills and sports motor skills in children and adolescents between 7 and 15 years of age. For each step of the validation process, we randomly withdrew a subsample of the full project’s sample (Table 1). Participants and their respective guardians signed an informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sport of the University of São Paulo. As an inclusion criterion, the participant could not demonstrate any physical and/or intellectual disability.

Table 1.

Number of participants included in each validation step

| Psychometric Properties | Participants by Age | Sex | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 15 | Male | Female | ||

| Decision Validity | 9 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| Reliability | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 15 | 30 |

| Objectivity Inter | 9 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| Objectivity Intra | 5 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 15 | 30 |

| Responssiveness | 27 | 9 | 39 | 12 | - | - | 43 | 44 | 87 |

Table 1 shows the number of participants evaluated in each step of the analyses. For decision validity, reliability and objectivity of the intra- and inter-evaluator, performance of the same subsample was used. To test the tool’s sensibility to differentiate proficient from non-proficient participants three groups were selected according to their experience in basketball. Participants between 7 and 10 years of age did not have any experience in basketball, the 11-year-old group already had some experience in basketball (physical education classes at school) and the 15-year-old group had at least 5 years of experience in basketball (participation in a competitive team of the school). This sample was used to allow variability between individuals in terms of the criteria evaluated here.

Speed-Dribbling Test

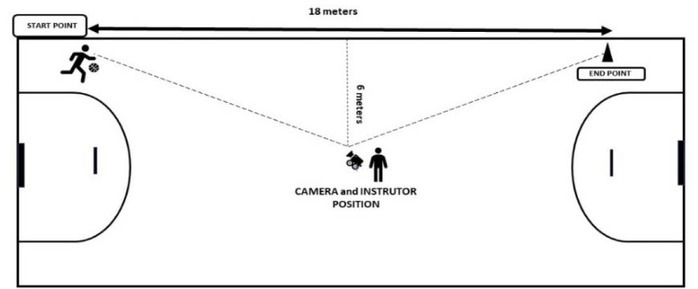

The speed-dribbling test required participants to cover, as fast as possible, 18 m in a straight line by running and bouncing the basketball with their preferred hand. There was no requirement to stop the dribbling exactly after the 18 m; “go-through” the course was allowed. First, the participant observed the evaluator demonstrating the skill and listened to the instructions. After demonstration, the participant performed the first attempt and, confirming that he/she understood the task, he/she executed another two attempts that were recorded for later evaluation. If the participant showed no understanding of the task, the evaluator demonstrated it again.

The camera was positioned laterally to the running path aiming at the half-distance point (9 m) to record the whole trajectory. All trials were recorded by a Sony HDR-PJ540 camera positioned at 6 m from the 9 m point of the path (Figure 1) and the videos were subsequently analyzed using Kinovea 0.8 software. One cone (which demarcated the distance of 18 m) and one ball (Penalty Basketball CBB Pro 7.5) were used for the execution of the test. After the last cone there were at least 3 m of free space (without any obstacle) for the deceleration movement.

Figure 1.

Position of the instructor

Evaluators

The criteria for the selection of the specialists for the domain validity process were: a) to have a degree in physical education; b) to have taught basketball to athletes and/or children for at least 10 years. For this process, 3 basketball specialists were invited (D1, D2 and D3).

To develop the golden standard (i.e., to classify each participant as proficient or non-proficient) for the decision validity and intra/inter-raters objectivity process, four other specialists, named GS1, GS2, B, and C were invited. All of them had a physical education degree. The raters GS1 and B also had experience in teaching basketball to athletes and/or children. The rater GS2 had experience in the analysis of fundamental movement skills. Given GS1 was the basketball specialist and did not know participants before the analysis, he was the main person responsible for the golden standard. Before starting the assessments, evaluators B and C watched and analyzed 10 children that trained under the GS2 supervision. Evaluators GS2 and C had taught 23 and 43, respectively, out of 50 children of the sample. In all steps of the current analyses, the videos were randomly presented.

Domain validity

The final version of the checklist (third version) was composed of 9 qualitative criteria (Table 2). All qualitative criteria were dichotomic: observance of criterion - 1 (one score), otherwise - 0 (zero score).

Table 2.

Checklist of the speed dribble skill

| Criteria | What should be evaluated? | Common Errors |

|---|---|---|

| C1 - Aerial Phase | The participant demonstrates the aerial phase for most of the steps during the course (50 + 1%). | The participant does not show the aerial phase. |

| C2 – Swing leg flexed approximately 90° while conducting the ball. | The participant flexes the balance leg at or near a 90o angle for most of the steps during the course (50 + 1%). | |

| C3 - Narrow positioning of the feet, landing on the heels (not flat foot) | The participant lands with the heel for most of the steps during the course (50 + 1%). | The participant lands with the foot flat. |

| C4 - Slight inclination of the trunk. | The trunk is tilted between 15 and 25⍛. | When the participant loses control of the ball and leans to recover ball control. The trunk is very steep (with an angle greater than 25⍛). |

| C5 - The participant controls the ball throughout the course. | The participant controls the ball throughout the course without losing it in no time. | The participant changes hands to keep control of the ball. The participant bounces the ball with both hands. |

| The participant does not perform the course in a straight line | ||

| C6 - Dominate the ball from the waist down. | The participant conducts the ball below the waistline. | The participant controls the ball above the waist line. |

| C7 - Eyes looking forward with the head up. | The participant completes the whole course directing the gaze (the head) forward (50 + 1%). | The participant looks at the ground or at the ball. |

| C8 - Push the ball with fingertips. | The participant bounces the ball by pushing it with his/her fingers. | The participant hits the ball with a rigid flat hand (with the palm or fingers) without accommodating the shape of the ball with the hand. |

| C9 – The ball forward and laterally (not in front of the body). | The participant bounces the ball diagonally to the body (laterally and forward) for most of the steps during the course (50 + 1%). | The participant leads the ball in front of the body. Participant conducts the ball to the side turning the trunk sideways. |

The first version of the checklist was prepared based on the basketball literature. The documents used were: Ferreira and Dante (2003) along with Cousy and Power (1975). This version was composed of 5 criteria. A pilot study was performed with 20 children (age = 7 – 10, without experience in basketball) performing the speed-dribbling test and evaluated by GS2. The results showed that these 5 criteria were not sufficient to differentiate between children with different levels of performance. Based on qualitative assessment of performance and the TGMD-II test (Ulrich, 2000), eight new criteria were added (the second version of the checklist). The same videos were reevaluated. The results showed better sensitivity of this version to identify children with different performance levels.

Three specialists (D1, D2, and D3) scored, based on a Likert scale (5 - fully agree, 4 - agree, 3 - undecided, 2 - disagree, 1 - completely disagree), each of the 13 qualitative criteria that composed the second version of the checklist. In this phase, they also had the option to add other criteria to the checklist if they considered it necessary. The criteria that at least two of the specialists scored as “fully disagree”, “disagree” or “undecided” were removed from the checklist. The process resulted in 5 criteria being withdrawn (arms in opposition to the legs; handle the ball for at least 4 consecutive times; touch the ball in the same point that the movement was originated; parallel shoulders while handle the ball; extended elbow at the moment of pushing the ball). Furthermore, an additional criterion was included (control of the ball throughout the course).

The final checklist version (third version) was presented to the same basketball specialists (D1, D2, D3). In this phase, they read all criteria and watched a video with a task demonstration. Then, following the same procedure (Likert scale), they rated the following questions: Does the checklist captures the fundamental components of speed dribbling? Does the checklist include all criteria for evaluating the speed dribble skill? Is there a relationship between the checklist criteria and the assessment that you make regarding the participant’s performance level? Is the checklist easy to apply? Does the information obtained by means of the checklist help correct the speed dribble skill?

Decision validity

The decision validity evaluates the accuracy of a given test to categorize correctly items in a checklist. The evaluation can be performed through the assessment of items which are known to be part of the categories. In the present case, validity was confirmed if the test adequately classified proficient criteria as proficient and non-proficient criteria as non-proficient (Safrit and Wood, 1995). In the present study, an a priori classification (the judgmental categorization) was made by GS1 and GS2.

For this process, a sample of 50 participants with different levels of basketball experience was used (athletes around 15 years of age; 11-year-old group; 7 – 10-year-old- group). From these, 7 belonged to the experienced group, 9 had already had some experience in basketball, and 34 never had any systematic instruction in the sport. Each of the 43 participants between 7 and 11 years of age fulfilled at least one non-proficient criterion in a way that all criteria showed non-proficiency in at least one child. The classification made by evaluators GS1 and GS2 became the gold standard. For decision the validity process conclusion, evaluator B assessed the same 50 participants and his/her results were compared to the gold standard. This was done to test the rate of false positive (non-proficient as proficient) or false negative responses (proficient as non-proficient).

Objectivity and Potential bias

The objectivity reflects whether different examiners provide the same assessment (inter-evaluator) and whether the same examiner makes the same assessment at different points in time (intra-evaluator) (Safrit and Wood, 1995). To calculate the inter-rater objectivity, we compared the gold standard with evaluators B and C, and B versus C. To calculate the intra-evaluator objectivity, after a one-week period, the evaluators (GS2, B and C) assessed 30 out of 50 children again.

The potential bias analysis was used to evaluate whether the evaluators had the tendency to classify false negative and false positive relative to the age or the level of proficiency.

Reliability and Responsiveness

The reliability reflects the test consistency when the same examinee is tested in repeated instances. For the present test, 30 children (15 boys and 15 girls) of different ages (between 7 and 11 years of age) were selected and evaluated by GS2 before and after a one-week interval. The one-week period was provided to assess consistency over a period that should not be influenced by either developmental processesand/or practice/learning (the participants did not practice basketball in their physical education class in this specific week period). Both tests were carried out at the same place with the same instructions.

The test must also be sensitive to detect changes in performance when changes in performance did occur (e.g., after intervention programs): this is the responsiveness of the test (Mokkink et al., 2012). To verify it, 87 children between 7 and 10 years of age participated in 10 training sessions to develop the quality of the speed-dribbling skill. The intervention occurred during the physical education classes once a week with 40 minutes of duration. In general, participants performed exercises and tasks with dribbling involved: dribbling between cones, dribbling around the court as fast as possible, adapted basketball games, and sprints while handling the ball. The analyses were made by GS2. Statistical Analyses

The statistical measure used to assess the validation was φ, suggested by Safrit and Wood (1995):

| (1) |

where a and d represent true positives (proficient) and negatives (non-proficient), respectively, and b and c represent false negatives and positives, respectively.

The reliability and objectivity analyses were performed using the Cohen’s κ coefficient (Mokkink et al., 2012; Safrit and Wood, 1995). The values of κ can be interpreted as weak (κ < 0.41), moderated (0.41 ≤ κ < 0.60), substantial (0.60 ≤ κ < 0.81), and high agreement (0.81 ≤ κ ≤ 1.00) (Landis and Koch, 1977). Besides κ, we used the percentage of agreement for the intra-rater concordance. This analysis calculated the percentage of cases in which the raters agreed on two different occasions.

Children’s performance in speed dribbling did not follow the assumptions of a normal distribution, thus, to assess the responsiveness after an intervention program, the Wilcoxon test for related samples was used.

To evaluate the possible bias, a comparison between proportions was made based on the z-statistics (Ott and Longnecker, 2010). From this test, we assessed whether a group had a higher chance to present false positives or false negatives than another group. We speculated that if evaluators were biased, this would occur in terms of the results of the younger groups presenting higher chances of demonstrating false negatives and the older groups presenting higher changes of demonstrating false positives. Thus, the 11-year-old group were tested against the youngest groups (10, 9, 8, 7-year-old group).

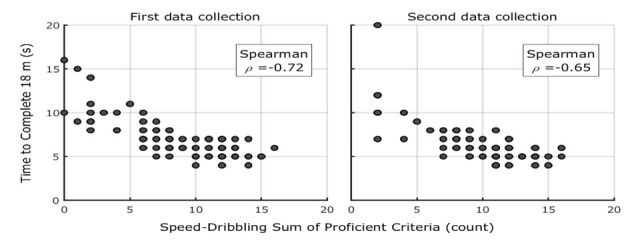

An extra analysis verified the relationship between the sum of proficient criteria (process of the movement) and time to complete the 18 m dribbling test (product of movement) for 87 children between 7 and 10 years old (mean 8.4; SD 1.1). The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used. All statistical analyses were made using Excel and SPSS 20.

Results

Domain and Decision Validation

Results of the domain validity of speed-dribbling skill criteria demonstrated high prevalence of positive evaluation (86% of responses were 5). Thus, evaluators considered that the checklist contained criteria that captured the fundamental aspects of the speed-dribbling skill. For decision validity, Table 3 presents the φ values for all criteria of the speed dribbling skill. The average value of φ was 0.85 ± 0.05 which indicates a high rate of assessment agreement.

Table 3.

Contingent φ for decision validity

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

Note -C = Criterion

Potential Bias

Among three evaluators, it was verified that one rater showed a greater chance to classify the 7-year-old group as false negative in relation to the 11-year-old group (p < .010). This occurred only for one group (8, 9 and 10-year-old children had the same chance of false negatives).

Reliability and Objectivity

Table 4 shows the Cohen’s κ and the percentage of agreement for the reliability and objectivity tests. There was high agreement between assessments separated by a one-week period of the same examinee (reliability) (average κ = .77), high agreement between different assessments of the same examinee from the same evaluator (intra-evaluator objectivity, average κ = .82), and high agreement for different evaluators assessing the same examinee (inter-evaluator objectivity, average κ = .77).

Table 4.

Reliability, inter and intra objectivity κ values and standard error

| Evaluator | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1-T2 (R) | .1 .00 | .1 .00 | .65 .32 | .86 .09 | .59 .14 | .65 .13 | .78 .21 | .1 .00 | .1 .00 |

| GS X B (IR) | .70 .16 | .79 .12 | .51 .16 | .77 .13 | .83 .13 | .79 .09 | .88 .12 | .68 .13 | 1 .00 |

| GS X C (IR) | .73 .18 | .79 .18 | .57 .16 | .60 .14 | .88 .08 | .75 .09 | .69 .16 | .47 .14 | .90 .06 |

| BX C (IR) | .70 .16 | .90 .17 | .78 .09 | .82 .09 | .94 .00 | .88 .07 | .78 .15 | .79 .09 | .90 .00 |

| GS (I) | .93 .72 | .1 .00 | .84 .16 | .86 .09 | .87 .09 | .83 .11 | .65 .32 | .80 .11 | .47 .30 |

| PA | 97% | 100% | 97% | 93% | 93% | 93% | 97% | 90% | 93% |

| B (I) | .80 .11 | .86 .09 | .81 .12 | .87 .09 | .77 .11 | .91 .09 | .89 .11 | .87 .09 | .73 .14 |

| PA | 90% | 93% | 93% | 93% | 90% | 97% | 97% | 93% | 90% |

| C (I) | .93 .06 | .73 .12 | 71 .18 | .63 .15 | .93 .06 | .90 .09 | .84 .16 | .93 .07 | .63 .23 |

| PA | 97% | 87% | 93% | 83% | 97% | 97% | 97% | 97% | 93% |

Note –R = Reliability; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; IR = Inter-raters; I = Intra-raters; C = Criteria; PA = Percentage Agreement

Responsiveness and Relationship Between the Process and the Product

Results showed changes in performance for the group of 87 children after a period of 10 classes (Median [Interquartile Range]; pre-intervention = 10 [6, 12]; post-intervention = 11 [8, 12]; z score = -3.82; p < .010; η2 = 0.17). Thus, the test was able to capture change in proficiency after the intervention.

Figure 2.

Time to complete the test on the first and second data collection (before and after the intervention).

Discussion

In the present study, we developed and validated a checklist to assess the process of movement in the speed-dribbling skill. The validation process followed the steps suggested by Safrit and Wood (1995), Barrow et al. (1989) and Mokkink et al. (2012). Results indicated that the speed-dribbling checklist presents the necessary components to assess this sport motor skill, is sensitive to differentiate between proficient and non-proficient performers, and presents good intra- and inter-rater reliability.

Specialists classified the checklist as easy to apply, suggesting that it would be possible to use the checklist in a variety of settings (e.g. in physical education classes). Nevertheless, Evaluator D2 was concerned about the need to record data for later evaluation, which requires additional time (the results cannot be assessed online). The evaluator rated this criterion (Is this test easy to apply?) as 4 (“agree”). This implies that this test did not reach the maximum feasibility.

Recent research compared the feasibility of fundamental movement skill assessments for preschool aged children (Klingberg et al., 2018). The TGMD-II test presented the lowest scores compared to other assessments tools. This may be associated to the fact that in the TGMD-II, as in our test, the evaluator should record the performance to, only later, evaluate participants. Although this extra step results in a longer process, the video increases the possibility of detecting less prominent errors in movement performance. It seems reasonable to suppose that video analysis could be the main factor in achieving high values of objectivity for intra- and inter-raters. After recording, examiners could watch a video repeatedly, in different velocities, pausing to appraise specific parts of the movement. Of importance is that the time spent on evaluating the video decreases with practice (≈ 5 min).

The test results demonstrated high consistency within and between raters in decision validity. Nevertheless, Evaluator C presented a tendency to show more false negatives for the youngest children when compared to the 11-year-old group. This might refer to the expectation to find more less-proficient individuals in younger groups. The expectation could also have come from the fact that the youngest group showed more non-proficient criteria than other groups. This would lead to a tendency to rate negatively (non-proficiency) this group when in doubt. These may be resolved by increasing the training set. Qualitative assessments require more training than quantitative ones (Klingberg et al., 2018; Stodden et al., 2008) and here the examiners were trained assessing only 10 children before the actual validation process. The third possibility is a statistical artifact. The expert group (11-year-old group) showed quite few instances of non-proficiency, which, combined with the small sample size for the analysis, biased the statistics to provide this result (Grant et al., 2017).

Importantly, evaluator C could have a bias resulting from his experience with these children (he taught 43 of the 50 participants). Nevertheless, κ (average and value for each criterion), ϕ and proportion of concordance showed high levels of agreement between evaluators. Our sample of evaluators had different previous knowledge on participants (GS2, B and C with some knowledge, GS1 with none) with our results (high inter-rater agreement) pointing to a null influence. Despite the good results, more research is needed to further test the checklist using different samples and statistical procedures.

The test results also showed consistent evaluations in two assessments separated by a one-week period. This result shows that the checklist is not over sensitive as it does not capture random variation present in repeated trials. As we can see, these results are sufficient to allow confidence in the stability of test scores over short periods of time.

Also, the checklist demonstrated responsiveness. After a period of practice, when participants increased their proficiency in the components of the skill, the test was able to capture this phenomenon. These results increase confidence in the test outcomes: it only demonstrates changes when systematic changes indeed occurred.

The results also demonstrated high association with the product of the movement (decreased time to complete the task; first data collection - 0.72 and second data collection - 0.65). This is an important feature as the literature of fundamental movement skills and sports pedagogy indicates that usually, improvement in movement quality leads to improvement in quantitative movement performance (Haubenstricker and Branta, 1997; Logan et al., 2014; Ré et al., 2018; Roberton and Konczak, 2001; Rudd et al., 2016). For instance, results indicate the relationship in throwing (Roberton and Konczak, 2001) hopping and long jumping (Logan et al., 2017).

Although the study of dribbling seems to be a concern of basketball research (Coelho et al, 2008; Erčulj et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2015), we did not find any studies that investigated the association between performance and quality of the movement. A possible explanation is the lack of tools that allow characterization of the movement process in speed dribbling. Nevertheless, it is known that, even with tools available, there are few studies that assess the process of movement in general (Robertson, 2013), which points to the lack of interest in this issue in the literature.

Nevertheless, the process of movement is highly relevant. Through such analysis, the researcher, instructor or teacher can identify limiting criteria for improvement in performance. For example, the rater can identify that the learner is driving the ball in front of, rather than laterally to the body (C9), thus having to slow the running speed not to hit the ball with his/her own body. Such analysis directs our strategies towards intervention and comprehension of the interacting components of a skill.

In the present sample, the criterion with lowest prevalence in our participants was C7 (Look forward – head up) and the most prevalent criteria were C1, C2 and C3 (i.e., swing phase, angle of leg flexion, landing with the heel). The latter observation corroborates with Ulrich (2000) who showed proficiency in these criteria in 90% of children older than 7 years of age. The former might be related to control strategies demonstrated by beginners, such as the use of visual feedback. C7 implies the ability to perform the task without relying on visual tracking of the ball. In beginners, visual feedback is used as the main source of information. With practice, performers tend to use other sources of information to correct the movement, such as tactile information, for instance (Katsuhara et al., 2010; Keogh and Sugden, 1985).

We concluded that the present checklist could be used to reliably analyze performance and evaluate the process of movement of the speed dribbling skill. This tool can be used in studies on related skills, also assisting in intervention learning and development of this and programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the teachers and coaches that collaborated to this validation process (Alessandro Capel do Nascimento, Miguel Centrone, Filomena Centrone, Gildasio de Araujo Barreto, Willians Manzini) and Colégio Sagrado Coração de Jesus.

Footnotes

Funding

FGS and MMP are funded by CAPES (Ministry of Education – Brazil) [88881.189575/2018-01] and (PNPD/CAPES 2019) respectively.

References

- Ali A. Measuring soccer skill performance: A review. Scand J Med Sci Spor. 2011;21:170–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidis N, Zacharakis E. The influence of the anthropometric characteristics and handgrip strength on the technical skills of young basketball players. J Phys Educ Spor. 2016. [DOI]

- Barrow HM, McGee R, Tritschler KA. Practical measurement in physical education and sport. Lea & Febiger; 1989.

- Coelho SMJ, Figueiredo AJ, Moreira CH, Malina RM. Functional capacities and sport-specific skills of 14- to 15-year-old male basketball players: Size and maturity effects. Eur J Sport Sci. 2008;8:277–285. doi: 10.1080/17461390802117177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cousy B, Power FG. Basketball; concepts and techniques. Allyn and Bacon: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Currell K, Jeukendrup AE. Validity, Reliability and Sensitivity of Measures of Sport Perforomance. Sports Med. 2008;38:297–316. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erčulj F, Blas M, Čoh M, Bračič M. Differences in Motor Abilities of Various Types of European Young Elite Female Basketball Players. Kinesiology. 2009;41:203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AEX, Dante DRJ. Basketball: techniques and tactics: a didactic-pedagogical approach. São Paulo: EPU; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Button CM, Snook B. An Evaluation of Interrater Reliability Measures on Binary Tasks Using d-Prime. Appl Psych Meas. 2017;41:264. doi: 10.1177/0146621616684584. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães E, Jones AB, Maia JAR, Santos A, Santos ET, Janeira MA. The role of growth, maturation, physical fitness, and technical skills on selection for a Portuguese under-14 years basketball team. Sports. 2017:7. doi: 10.3390/sports7030061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubenstricker J, Branta C. Clark JE, Humphrey J. Motor Development: Research and Reviews. Reston, VA: National Association for Sport and Physical Education; 1997. The relationship between distance jumped and developmental level on the standing long jump in young children; pp. 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuhara Y, Fuji S, Kametani R, Oda S. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Rhythmic, Stationary Basketball Bouncing in Skilled and Unskilled Players. Percept Motor Skill. 2010;110(2):469–478. doi: 10.2466/pms.110.2.469-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh J, Sugden DA. Movement skill development. Macmillan Pub Co; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg B, Schranz N, Barnett LM, Booth V, Ferrar K. The feasibility of fundamental movement skill assessments for pre-school aged children. J Sport Sci. 2018;00(00):1–9. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1504603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Z, Qi F, Shi Q. The influence of basketball dribbling on repeated high-intensity intermittent runs. J Exer Sci Fitness. 2015;13(2):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data Data for Categorical of Observer Agreement The Measurement. Biometrics. 1977. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lehane J. Basketball Fundamentals: teaching techniques for winning (3rd ed.) Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Leite N, Coelho E, Sampaio J. Assessing the importance given by basketball coaches to training contents. J Hum Kinet. 2011;30(1):123–133. doi: 10.2478/v10078-011-0080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan SW, Barnett LM, Goodway JD, Stodden DF. Comparison of performance on process-and product-oriented assessments of fundamental motor skills across childhood. J Sport Sci. 2017;35(7):634–641. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1183803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan SW, Robinson LE, Rudisill ME, Wadsworth DD, Morera M. The comparison of school-age children’s performance on two motor assessments: The Test of Gross Motor Development and the Movement Assessment Battery for Children. Phys Educ Sport Peda. 2014;19(1):48–59. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2012.726979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Vine K, Larkin D. The relationship of process and product performance of the two-handed sidearm strike. Phys Educ Sport Peda. 2007;12(1):61–76. doi: 10.1080/17408980601060291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, de Vet HC. The COSMIN checklist manual. VU University Medical. 2012;56 doi: 10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. Basketball Fundamentals (1st ed.) Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ré AHN, Logan SW, Cattuzzo MT, Henrique RS, Tudela MC, Stodden DF. Comparison of motor competence levels on two assessments across childhood. J Sport Sci. 2018;36(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1276294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberton MA, Konczak J. Predicting Children´s Overarm Throw Ball Velocities From Their Developmental Levels in Throwing. Res Q Exercise Sport. 2001;72:91–103. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2001.10608939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SJ, Burnett AF, Cochrane J. Tests examining skill outcomes in sport: A systematic review of measurement properties and feasibility. Sports Med. 2013;44(4):501. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0131-0. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd J, Butson ML, Barnett L, Farrow D, Berry J, Borkoles E, Polman R. A holistic measurement model of movement competency in children. J Sport Sci. 2016a;34(5):477–485. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1061202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd J, Butson ML, Barnett L, Farrow D, Berry J, Borkoles E, Polman R. A holistic measurement model of movement competency in children. J Sport Sci. 2016b;34(5):477–485. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1061202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safrit MJ, Wood TM. Introduction to measurement in physical education and exercise science. William CB; 1995.

- Scanlan AT, Tucker PS, Dascombe BJ, Berkelmans DM, Hiskens MI, Dalbo VJ. Fluctuations in activity demands across game quarters in professional and semiprofessional male basketball. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(11):3006–3015. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt V. Developmental motor patterns: implications for elementary school physical education. Psychology of Motor Behavior and Sport. 1980. pp. 314–323. –.

- Stodden DF, Goodway JD, Langendorfer SJ, Roberton MA, Rudisill ME, Garcia C, Garcia LE. A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: An Emergent Relationship. Quest. 2008;60(2):290. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2008.10483582. –. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strand B, Wilson R. Assessing sport skills (2nd ed.) Champaign, IL: Hunan Kinectics; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Strumbelj E, Erculj F. Analysis of Experts’ Quantitative Assessment of Adolescent Basketball Players and the Role of Anthropometric and Physiological Attributes. J Hum Kinet. 2014;42(1):267–276. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2014-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summit PH, Jennings D. Basketball: fundamental and tema play (2nd ed.) Boston: McGraw_Hill Companies; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich D. Test of gross motor development examiner’s manual (2nd ed.) Austin: Proed; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wierike SCM, Elferink-Gemser MT, Tromp EJY, Vaeyens R, Visscher C. Role of maturity timing in selection procedures and in the specialisation of playing positions in youth basketball. J Sport Sci. 2015;33(4):337. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.942684. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]