Abstract

The application of high-voltage electrostatic field (HVEF) is a novel method of thawing. To determine if HVEF thawing could lead to sarcoplasmic proteins denaturation, and to provide a theoretical estimation of the structure of the sarcoplasmic proteins, pork tenderloin was thawed by traditional and HVEF methods. The results from protein solubility analysis, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and differential scanning calorimeter showed that HVEF thawing did not result in more protein denaturation than those thawed under air or running water. From the principal component analysis of FTIR raw spectra (1700–1600 cm−1, Amide I region), we observed some separations of samples with different thawing treatments. It was found that the proportions of α-helix (1650–1640 cm−1 spectral bands in the original data) could lead to the differences on the PC2 axis of score plots.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-020-04253-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pork tenderloin, HVEF, Sarcoplasmic proteins, Denaturation

Introduction

The HVEF thawing technique is faster and results in higher quality products compared to other thawing methods (Dalvi-Isfahan et al. 2016). Although there have been some studies on the protein changes of the HVEF-thawed meat (Jia et al. 2018; Rahbari et al. 2018), only a few of them focused on the sarcoplasmic proteins that are closely related to meat color. Earlier research found that there was little impact of HVEF thawing on the oxidation and denaturation of sarcoplasmic proteins in rabbit meat and myofibrillar proteins in pork, respectively (Jia et al. 2017a, 2018). For meat processing, the protein structural modifications were related to the protein aggregation behavior and protein functionalities (Xia et al. 2010; Mitra et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2011). Vibrational spectroscopy, especially Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), is widely used for the investigation of protein secondary-structures (Mitra et al. 2017; Perisic et al. 2013). For the proteins, there are many normal modes of the amide groups, e.g. Amide I, Amide II, Amide III, Amide A and B skeletal groups, all of which have a higher vibrational frequency than other amide groups (Barth and Zscherp 2002). Although analysis of Amide I (1700–1600 cm−1) of proteins for the secondary structure estimation is common, the Amide III region (1350–1200 cm−1) has also been utilized in protein structural analysis (DeOliveira et al. 1994). There were many attempts on quantitative information extraction for protein secondary structures (Mitra et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2011). The methods always included spectral-band narrowing and curve fitting (Surewicz et al. 1993). However, the band narrowing (e.g. Fourier deconvolution and Fourier derivation) procedures might amplify the noise significantly, which could incorrectly be misinterpreted as a real spectral-band (Surewicz et al. 1993). To reduce interpretation ambiguities from “ghost spectral-bands” we apply the same fitting procedures—including base-functions and number of peaks—on all measurements in our study, which was focused on the modest protein denaturation of the thawed pork.

Aims of the present study were (1) to investigate the possible structural changes of sarcoplasmic proteins extracted from the thawed pork with HVEF and traditional methods, (2) to investigate the effects of HVEF on the denaturation of sarcoplasmic proteins in pork, and (3) to assess the possibility for using the HVEF thawing on rapid food thawing process.

Materials and methods

Sarcoplasmic protein preparation

Fresh pork tenderloin at 24 h post-mortem was obtained from a meat market. The product was cut into cuboids (50 × 50 × 10 mm, 45.3 ± 2.5 g) and samples were randomly assigned to four thawing groups (air, running water and HVEF at two levels) and stored at − 20 °C until thawing. Air thawing and running water (RW) thawing were used as controls. The HVEF thawing experimental setup and the conditions (50 mm inter-electrode distance) were the same as explained in previous work (Jia et al. 2017b, 2018). The voltages used in this study were − 10 kV and − 20 kV. Immediately after thawing, the sarcoplasmic protein was extracted with the method reported by Tadpitchayangkoon et al. (2010) with some modifications. The minced pork was homogenized with cold deionized water and then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min. The precipitate was centrifuged again (10,000 g, 10 min). The supernatants from these two centrifugations were collected as the sarcoplasmic protein solution and lyophilized for further analysis. The protein samples extracted from fresh pork were similarly prepared for protein structure analysis.

Protein solubility

The solubility of sarcoplasmic protein was determined according to the method reported by Tadpitchayangkoon et al. (2010) with some modifications. 0.5 g of the lyophilized sarcoplasmic proteins was mixed with 10 mL of cold deionized water. After centrifugation at 8000 g and 4 °C for 30 min, the protein content of the supernatant was determined the measuring the absorbance at 280 nm using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The protein concentration is given in mg protein·mL−1 water. Triplicate measurements were carried out.

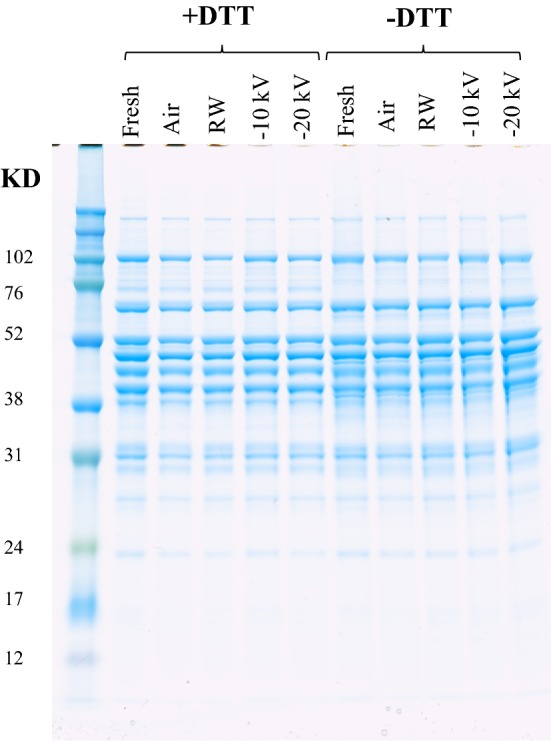

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Reducing (10 μL of 1 M DTT) and non-reducing conditions were employed to determine the presence of disulfide bonds (Grossi et al. 2016). The amount of protein loaded in each SDS-PAGE lane was 7.5 μg. After mixing with 25 µL NuPAGE LDS sample buffer, samples and markers were heated to 80 °C for 10 min, and were further separated using NuPAGETM 12% Bis–Tris Gels (Novex, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Electrophoresis was carried out at 200 V. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G and scanned with a SilverFast Ai IT8 Studio (Multi-Exposure) Version 6.6 (Epson Perfection V 750 Pro).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The IR spectra of the pork samples were measured as described by Mitra et al. (2017). Sample surfaces were wiped with a paper tissue to remove surface moisture and positioned on an attenuated total reflectance accessory (DuraScope, SensIR Technologies, Connecticut, USA) connected to a MB100 FT-IR spectrometer (Bomem, Quebec, Canada). The equipment was continuously purged with dried air to remove traces of water vapor and CO2 which could affect the background reading. Spectra were obtained in the wavenumber range from 4000 to 400 cm−1 with 4 cm−1 resolution and 64 scans. From the raw data, two selected regions of each spectrum—from 1610 to 1700 and 1350 to 1200 cm−1—were normalized and processed by Fourier Self-Deconvolution (FSD) function. This will assist in reducing the overlap of subcomponent bands. Following the FSD, a multi-peak fitting procedure was performed with a Lorentzian profile to quantify the different peak areas within the subcomponent bands. The band assignments for Amide I and Amide III frequencies were determined based on the studies of Jackson and Mantsch (1995) and Singh et al. (1993). Formulae for calculating the parameters are as follows:

For Amide I,

For Amide III,

DSC

Changes in thermal stability of sarcoplasmic proteins in the pork tenderloin were analyzed using a Differential Scanning Calorimeter (Mettler Toledo, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland) according to the method reported by Tadpitchayangkoon et al. (2010) with modifications. The heating rate and temperature scanning range were 10 °C·min−1 and 25–95 °C, respectively. The corresponding denaturation temperatures of the peaks were determined.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed at least in triplicate, and the data are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation (SD). The least significant difference procedure was used to compare the mean values using a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

SDS-PAGE of sarcoplasmic proteins

SDS-PAGE patterns of sarcoplasmic proteins extracted from thawed pork are shown in Fig. 1. Sarcoplasmic proteins of pork tenderloin contain various proteins with major molecular weight (mol wt) fractions ranging from 20 to 100 kD (Fig. 1). Myofibrillar proteins, particularly myosin (MW = 220 kDa), can be considered as insignificant fractions, implying that mostly sarcoplasmic proteins are extracted by the procedure applied in this study.

Fig. 1.

Influence of different thawing methods on the SDS-PAGE patterns of sarcoplasmic proteins extracted from pork

The identification of sarcoplasmic proteins was reported by Picariello et al. (2006). There are many proteins separated by the SDS-PAGE in this work, e.g. glycogen phosphorylase, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, pyruvate kinase muscle isozyme, phosphoglycerate kinase 1 and creatine kinase. There are some differences observed for the SDS-PAGE patterns between proteins with and without DTT treatment, e.g. some different protein fragments or aggregates shown in the SDS-PAGE. As there are few differences of band intensities between different thawing treatment groups in the presence or absence of DTT, it is concluded that there was no severe oxidation during the pork thawing process.

Protein denaturation

Figures S2 and S3 show the FTIR interpretation of the Amide I and Amide III region for all the samples. The manipulation by the FSD function on the spectra could isolate the overlapping bands. It should be noted here that somewhat different results of protein structures are found using the different resolution enhancements in the software routines, employing different mathematical techniques (FSD or derivation), assumed number of overlapping bands, etc. To justify a quantitative comparison we fixed these parameters for all spectra deconvolutions. As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences in the proportions of β-sheet, α-helix and antiparallel β-sheet for the Amide I and the Amide III region. The PCA score plots of raw spectral data are shown in Figure S4, the corresponding spectral loadings in Figure S5. In the PC2 direction in Figure S4A, the most isolated group is the fresh pork. Through inspection of the loadings in Figure S5A, the difference could be associated with the range 1650–1640 cm−1, which was accounted for the differences in the proportions of the α-helix structure. The peaks coupled with the β-sheet or other structures could not be distinguished in the loading plot (Figure S5A).

Table 1.

Solubility and contents of secondary band information parameters of the sarcoplasmic proteins from thawed pork

| Protein solubility (mg mL−1) |

β-sheet Amide I (%) |

α-Helix Amide I (%) |

Antiparallel β-sheet Amide I (%) |

β-sheet Amide III (%) |

α-Helix Amide III (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 28.95 ± 0.37a | 58.30 ± 1.64d | 27.64 ± 2.20a | 14.06 ± 0.60b | 62.42 ± 3.03b | 37.58 ± 3.03a |

| Air | 26.75 ± 0.74b | 61.34 ± 2.08bc | 23.51 ± 1.17bc | 15.15 ± 0.97a | 72.67 ± 1.66a | 27.33 ± 1.66b |

| RW | 24.46 ± 0.25c | 62.92 ± 1.60b | 22.50 ± 0.77c | 14.58 ± 0.96ab | 67.51 ± 5.53b | 32.49 ± 5.53a |

| HVEF (− 10 kV) | 26.50 ± 0.62b | 60.60 ± 0.50c | 24.17 ± 0.32b | 15.23 ± 0.46a | 65.68 ± 1.73b | 34.32 ± 1.73a |

| HVEF (− 20 kV) | 28.89 ± 0.49a | 65.50 ± 1.43a | 21.99 ± 1.01c | 12.50 ± 0.54c | 63.65 ± 1.73b | 36.35 ± 1.73a |

Results presented as mean values ± SD of at least 4 replicates. Different letters in each row indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

The different results from analyzing the Amide I and Amide III spectral ranges should be caused by the different amide vibrations. However, it was found that there were no noticeable changes in the α-helix or β-sheet contents of sarcoplasmic proteins when the pork was thawed by HVEF compared with other thawing methods in this study. There is an expected impact on the protein solubility with the degree of the protein folding or aggregation. It should be mentioned here that the protein solubility did not decrease significantly after the HVEF treatment (Table 1), which was in agreement with the infrared spectroscopy data. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to quantify the association between protein solubility and proportions of α-helix for the Amide I and the Amide III region, determined at 0.429 and 0.564, respectively.

For the thermal denaturation pattern of the sarcoplasmic proteins extracted from differently thawed groups, there were significant differences in the DSC curves from the fresh pork tenderloin compared with those from the thawed pork (Fig. 2). There were exothermic peaks around 29, 36 and 92 °C for the sarcoplasmic proteins extracted from fresh samples, indicating the aggregation of sarcoplasmic proteins, while there were only two exothermic peaks for the other thawed samples. Based on the results of FTIR, DSC, protein solubility and the SDS-PAGE, it could be concluded that the HVEF thawing used in our work does not lead to significant denaturation of sarcoplasmic proteins, which indicated that some pork quality indicators, e.g. color and water holding capacity, might not be influenced by the HVEF thawing process either. This study is a supplementary material to analyze the HVEF thawing on the protein changes from thawed pork, in combination with the previous work for myofibrillar proteins (Jia et al. 2018). It could be concluded that the HVEF thawing (− 10 kV, 5 cm) did not affect the protein denaturation. So this work provides a theoretical foundation for the industrial application of this innovative food thawing method.

Fig. 2.

DSC thermograms of sarcoplasmic proteins from thawed pork tenderloin. Each data is the average of three replicate samples

Conclusion

In this study, frozen pork tenderloin was thawed under various conditions. Based on the acquired results, the HVEF treatment used in this study did not cause more denaturation of sarcoplasmic proteins in pork when compared with conventional thawing conditions. The results from Amide I and Amide III were different for the different amide vibrations in FTIR. The proportions of α-helix structure for the Amide I and the Amide III region of fresh groups were the highest, indicated that the thawing process would disrupt the α-helix structure of sarcoplasmic proteins, while the HVEF thawing methods had less effect on the decrease of α-helix structure or shift of β-sheet.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. BLX201914). The authors express gratitude to China Scholarship Council. This work was also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (“Study on the characteristics and mechanism of freezing and thawing of meat under high-voltage electrostatic field”, Grant Number 31571908).

Footnotes

Chemical compounds studied in this article: Sodium dodecyl sulfate (PubChem CID: 3423265).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guoliang Jia, Email: jiaguoliang@cau.edu.cn.

Frans van den Berg, Email: fb@food.ku.dk.

Han Hao, Email: haohan@bupt.edu.cn.

Haijie Liu, Email: liuhaijie@cau.edu.cn.

References

- Barth A, Zscherp C. What vibrations tell about proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 2002;35(4):369–430. doi: 10.1017/S0033583502003815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvi-Isfahan M, Hamdami N, Le-Bail A, Xanthakis E. The principles of high voltage electric field and its application in food processing: a review. Food Res Int. 2016;89:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeOliveira DB, Trumble WR, Sarkar HK, Singh BR. Secondary structure estimation of proteins using the amide III region of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: application to analyze calcium-binding-induced structural changes in calsequestrin. Appl Spectrosc. 1994;48(11):1432–1441. doi: 10.1366/0003702944028065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi A, Olsen K, Bolumar T, Rinnan Å, Øgendal LH, Orlien V. The effect of high pressure on the functional properties of pork myofibrillar proteins. Food Chem. 2016;196:1005–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Mantsch HH. The use and misuse of FTIR spectroscopy in the determination of protein structure. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30(2):95–120. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Liu H, Nirasawa S, Liu H. Effects of high-voltage electrostatic field treatment on the thawing rate and post-thawing quality of frozen rabbit meat. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2017;41:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2017.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, He X, Nirasawa S, Tatsumi E, Liu H, Liu H. Effects of high-voltage electrostatic field on the freezing behavior and quality of pork tenderloin. J Food Eng. 2017;204:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Nirasawa S, Ji X, Luo Y, Liu H. Physicochemical changes in myofibrillar proteins extracted from pork tenderloin thawed by a high-voltage electrostatic field. Food Chem. 2018;240:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra B, Rinnan Å, Ruiz-Carrascal J. Tracking hydrophobicity state, aggregation behaviour and structural modifications of pork proteins under the influence of assorted heat treatments. Food Res Int. 2017;101:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perisic N, Afseth NK, Ofstad R, Narum B, Kohler A. Characterizing salt substitution in beef meat processing by vibrational spectroscopy and sensory analysis. Meat Sci. 2013;95(3):576–585. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picariello G, De Martino A, Mamone G, Ferranti P, Addeo F, Faccia M, SpagnaMusso S, Di Luccia A. Proteomic study of muscle sarcoplasmic proteins using AUT-PAGE/SDS-PAGE as two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J Chromatogr B. 2006;833(1):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahbari M, Hamdami N, Mirzaei H, Jafari SM, Kashaninejad M, Khomeiri M. Effects of high voltage electric field thawing on the characteristics of chicken breast protein. J Food Eng. 2018;216:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BR, DeOliveira DB, Fu FN, Fuller MP. Fourier transform infrared analysis of amide III bands of proteins for the secondary structure estimation. Biomol Spectrosc III. 1993;1890:47–56. doi: 10.1117/12.145242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Zhou F, Zhao M, Yang B, Cui C. Physicochemical changes of myofibrillar proteins during processing of Cantonese sausage in relation to their aggregation behaviour and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2011;129(2):472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surewicz WK, Mantsch HH, Chapman D. Determination of protein secondary structure by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: a critical assessment. Biochemistry. 1993;32(2):389–394. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadpitchayangkoon P, Park JW, Mayer SG, Yongsawatdigul J. Structural changes and dynamic rheological properties of sarcoplasmic proteins subjected to pH-shift method. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(7):4241–4249. doi: 10.1021/jf903219u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X, Kong B, Xiong Y, Ren Y. Decreased gelling and emulsifying properties of myofibrillar protein from repeatedly frozen-thawed porcine longissimus muscle are due to protein denaturation and susceptibility to aggregation. Meat Sci. 2010;85(3):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.