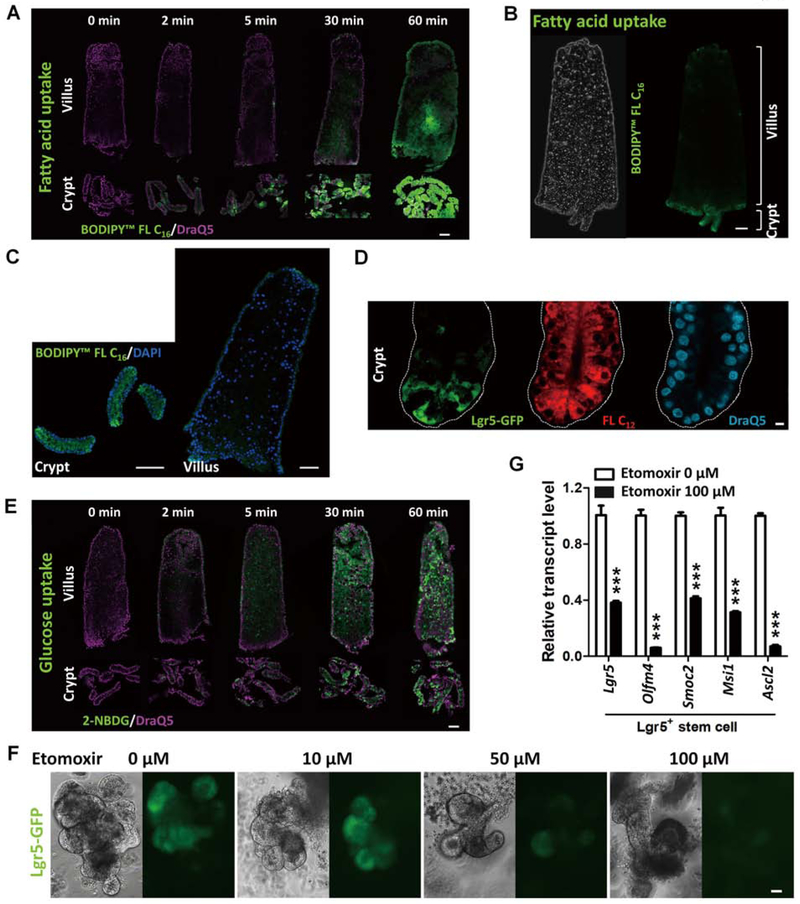

Figure 1. FAO is required for intestinal stem cell renewal.

(A-E) Intestinal crypts uptake fatty acid more readily than villi (n=3 independent experiments). Crypt and villus epithelial cells were isolated from the proximal half of the small intestine (from the midpoint between gastroduodenal junction to ileal-cecal junction) and incubated with 10 μM BODIPY™ FL C16 (fluorescent palmitic acid), FL C12 (fluorescent dodecanoic acid), or 10 μM 2-NBDG (fluorescent glucose analog), respectively. Similar results are seen in duodenum, jejunum and ileum (Fig. S1B). (A) Time-course study of fluorescent fatty acid (BODIPY™ FL C16) uptake shows that intestinal crypt cells uptake more fatty acid than villus cells (scale bar, 50 μm). (B-C) Fatty acid (green fluorescence) accumulates more in the crypt cells than in villus cells (scale bars, 50 μm). (D) Red fluorescent fatty acids (10 μM BODIPY™ FL C12, 5 min) are observed in Lgr5-GFP stem cells in the crypts (scale bar, 5 μm). (E) Glucose uptake in crypt and villus cells (scale bar, 50 μm). (F) Fewer Lgr5-GFP cells are observed in organoids treated with Etomoxir (fatty acid oxidation inhibitor) for 72 hours (n=3 independent experiments). (G) qRT-PCR shows a significant decrease in the transcript levels of intestinal Lgr5+ stem cell markers in the organoids treated with 100 μM Etomoxir for 72 hours. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3–4 independent organoid cultures per treatment, Student’s t-test, two-sided at P < 0.001***).