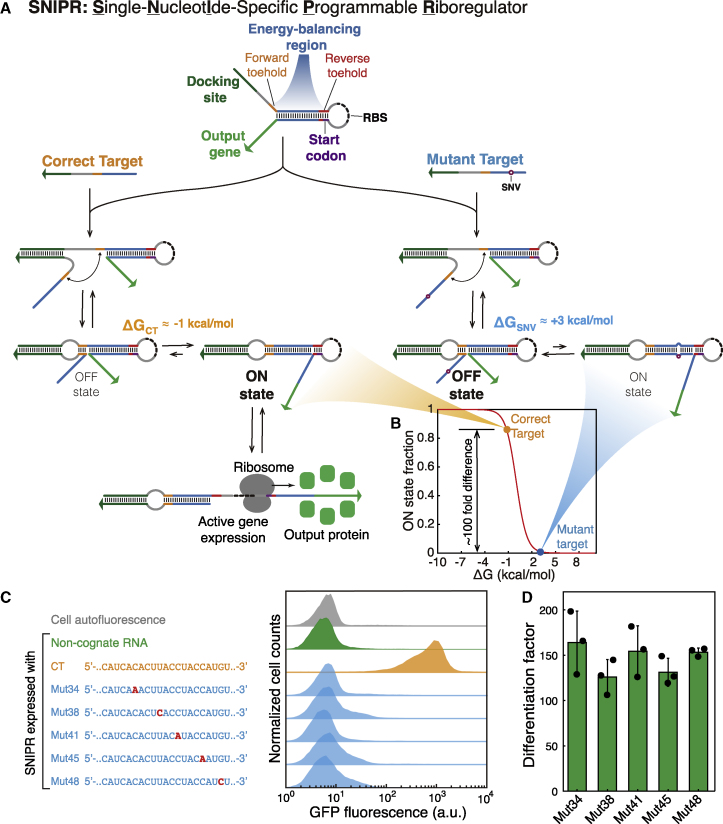

Figure 1.

SNIPR Design Principles and Validation Using Flow Cytometry

(A) SNIPRs have a docking site (dark green) used to promote binding to the target RNA and a secondary structure that conceals the ribosomal binding site (RBS) and start codon. After target RNA binding, an energy-balancing region containing forward (orange) and reverse (red) toeholds enables single-nucleotide-specific transcript detection based on toehold-mediated strand displacement. The correct target with a perfectly matched sequence forms the active ON state with favorable reaction free energy, while a mutant target leads to a mismatch that makes the ON state very thermodynamically unfavorable. Formation of the ON state with the correct target exposes the RBS and start codon for active translation of the output protein.

(B) The fraction of target-SNIPR complexes in the ON state varies with the reaction energy of the OFF-to-ON state transition. For the correct target, the reaction energy is −1 kcal/mol and the corresponding ON state fraction is 0.836. For a mutant target, the reaction energy is ~3 kcal/mol and the corresponding ON state fraction is reduced to 0.008.

(C) Flow cytometry GFP fluorescence histograms for SNIPRs operating in E. coli after 3 h of IPTG induction. Strong GFP production is only observed for the correct target. Mut34 to Mut48 differ from the correct target with point mutations at positions 34 to 48, respectively, from the 5′ end and do not activate the SNIPR.

(D) The differentiation factor of the SNIPR upon binding to the mutant targets in (C). The differentiation factor is the ratio of protein expression generated by the correct target to that induced by the mutant target (n = 3 biological replicates; bars represent the arithmetic mean of the flow cytometry geometric mean of each replicate ± SD).