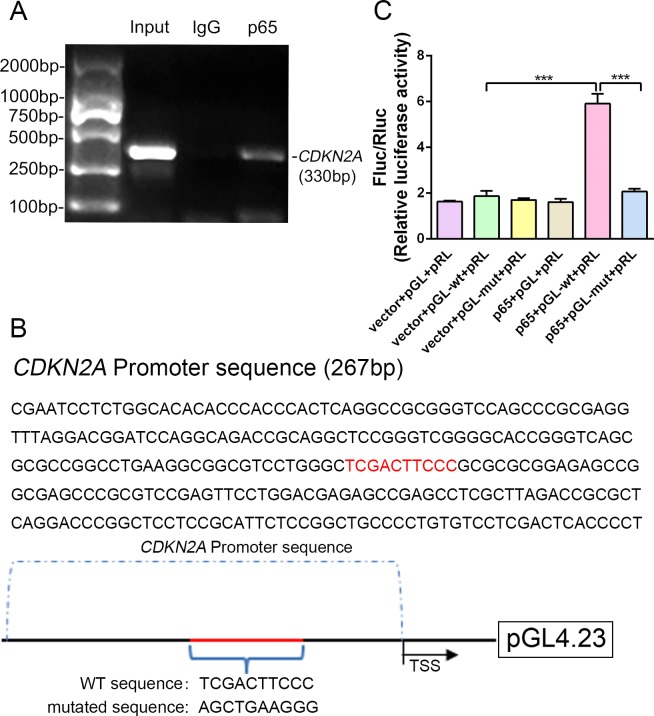

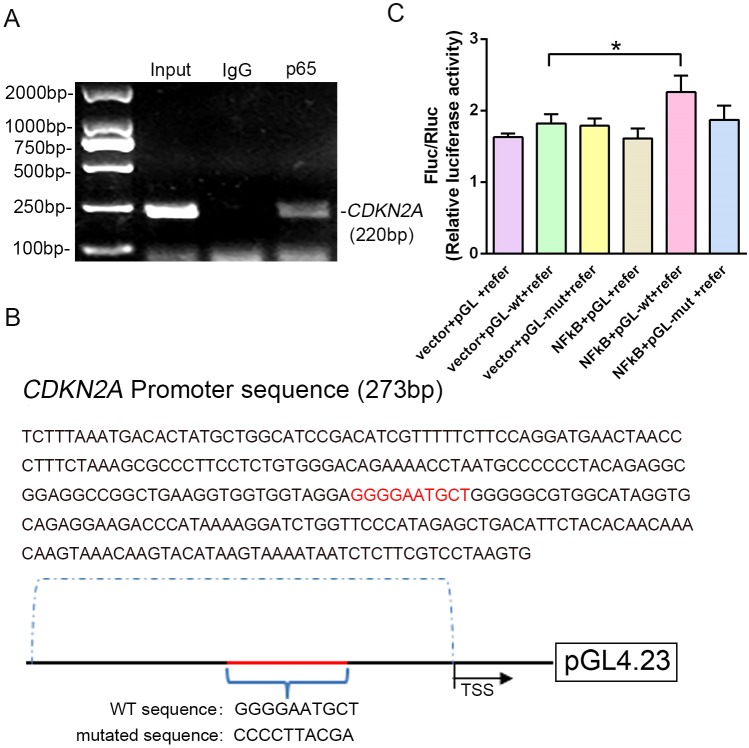

Figure 6. NF-κB-p65 bound the CDKN2A gene promoter and promoted p16 expression in human NP cells.

(A) CDKN2A promoter sequences were recovered by PCR from p65 immunoprecipitates. (B) p65‐like elements in the human CDKN2A promoter region and the mutated sequence are marked in red (upper panels). Below: structural schematic of the WT and mutant pGL4.23-p16 promoter reporter plasmids. (C) Luciferase activity driven by the CDKN2A promoter was more pronounced following NF-κB treatment. By contrast, luciferase activity that was not driven by the CDKN2A luciferase reporter decreased in the absence of NF-κB, and luciferase activity not driven by the mutant CDKN2A luciferase reporter decreased upon NF-κB treatment. Data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 3); ***p<0.001.