Abstract

Purpose:

‘False consensus’ refers to individuals with (vs. without) an experience judging that experience as more (vs. less) prevalent in the population. We examined the role of people’s perceptions of their social circles (family, friends, and acquaintances) in shaping their population estimates, false consensus patterns, and vaccination intentions.

Methods:

In a national online flu survey, 351 participants indicated their personal vaccination and flu experiences, assessed the percent of individuals with those experiences in their social circles and the population, and reported their vaccination intentions.

Results:

Participants’ population estimates of vaccination coverage and flu prevalence were associated with their perceptions of their social circles’ experiences, independent of their own experiences. Participants reporting less social circle ‘homophily’ (or fewer social contacts sharing their experience) showed less false consensus and even ‘false uniqueness.’ Vaccination intentions were greater among non-vaccinators reporting greater social circle vaccine coverage.

Discussion:

Social circle perceptions play a role in population estimates and, among individuals who do not vaccinate, vaccination intentions. We discuss implications for literatures on false consensus, false uniqueness, and social norms interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, psychologists have defined ‘false consensus’ as individuals with (vs. without) an experience judging that experience as more prevalent in the population.1 Perceiving more false consensus may promote distrust in communications that contradict one’s views, and undermine behavior change.2,3 Explanations of false consensus have focused on people over-weighing personal experiences when assessing population estimates, due to knowing more about themselves (vs. others), and wanting to believe that others are like them.4,5

Alternatively, false consensus in population estimates may stem from ‘homophily’ or selective exposure to like-minded peers.1 For example, sexually active college women estimated more sexual activity among college women in general, due to having more sexually active friends.6 Recent social sampling models suggest that people have relatively accurate perceptions of their social contacts, which inform their population estimates and behavioral intentions.7,8,9,10 Most people socialize with like-minded others,11 but those reporting less like-minded social circles should show relatively less false consensus and greater willingness to change.8

In a national flu survey, participants reported on vaccination and flu experiences, for themselves, their social circles, and the population. We examined whether (1) participants with (vs. without) the experience reported larger population estimates for that experience, replicating false consensus; (2) population estimates were predicted by social circle perceptions, even after accounting for false consensus or correlations between population estimates and personal experiences; (3) participants reporting less like-minded social circles showed less false consensus in their population estimates; (4) vaccination intentions were associated with reported population estimates and social circle perceptions, and whether these relationships varied by personal experience.

METHODS

Sample

We conducted secondary analyses of an online survey with RAND’s American Life Panel,12,13 which was recruited nationally through probability-based approaches.14 Panelists regularly complete online surveys for about $20 per 30 minutes, and receive equipment and internet access if needed.

Between September 2011 and February 2013, 493 of 598 (82%) invited panelists completed all measures analyzed here. To ensure that questions about ‘the past year’ included the 2010–11 flu season, we restricted analyses to 351 of 493 respondents (71%) surveyed in September 2011, before the 2011–12 flu season. This restriction did not affect focal measures (Table S1) or main findings.

Procedure

RAND’s Human Subjects Protection Committee approved the survey.15 All participants gave informed consent. The questions below were analyzed here.

Personal experiences.

Participants answered “During the last flu season (Fall 2010 to Spring 2011), did you get a seasonal flu vaccine (either a shot or nasal spray)?” and “During the last flu season (Fall 2010 to Spring 2011), did you ever have [flu] symptoms?” described as “fever and a cough or sore throat.”16 Responses included “yes,” “no,” and “I don’t remember” coded as missing (3% for vaccination; 4% for flu.)

Social circle perceptions.

Participants were asked to “think of all the people you know, who know you, and who you’ve had regular contact with in the past six months” which could be “face-to-face, by phone or mail, or on the internet.” They assessed how many included family members, close friends, coworkers, school or childhood relations, people who provide you a service, neighbors, and others. Subsequently, participants answered “Of [all] people in your social circle: How many are you sure got vaccinated for the flu in the past year?” and “How many are you sure did not get vaccinated for the flu in the past year?” For remaining social contacts, participants estimated how many they thought got vaccinated. Perceived social circle vaccine coverage reflected participants’ reported percent of vaccinated social contacts, across confidence levels (i.e., known and suspected vaccinations). Analogous questions assessed perceived percent of social circles getting flu in the past year. We also computed ‘homophily’ or like-mindedness, as the perceived percent of social circles who shared participants’ experience of getting vaccinated (vs. not) or getting flu (vs. not).

Population estimates.

Participants answered “In a typical year, how many out of every 100 people in the United States do you think get vaccinated against the flu?” and “In a typical year, how many out of every 100 people in the United States do you think catch the flu and develop flu symptoms?”

Vaccination intentions.

Participants assessed “the chances that you will choose to get the influenza vaccine this flu season (Fall 2011 and Spring 2012)” on a 0–100% scale.

Analysis plan

Analyses were conducted for vaccination and flu. To test research question 1, we computed t-tests and Pearson correlations reflecting relationships between population estimates and personal experiences or false consensus (Figure 1; Table 1). To test research question 2, we computed linear regressions predicting population estimates from social circle perceptions, personal experiences, and both (Table 2). Robustness checks examined whether the role of social circle perceptions held when dichotomizing that measure, or interacted with personal experiences or characteristics of social circle perceptions (Table S2–S3). To test research question 3, linear regressions examined whether homophily in social circles interacted with personal experience when predicting population estimates. To test research question 4, linear regressions predicted vaccination intentions from reported population estimates and social circle perceptions, and tested whether own experiences moderated these relationships (Table 3). All linear regressions included demographic control variables. We computed correlations associated with regression models (Table S4).

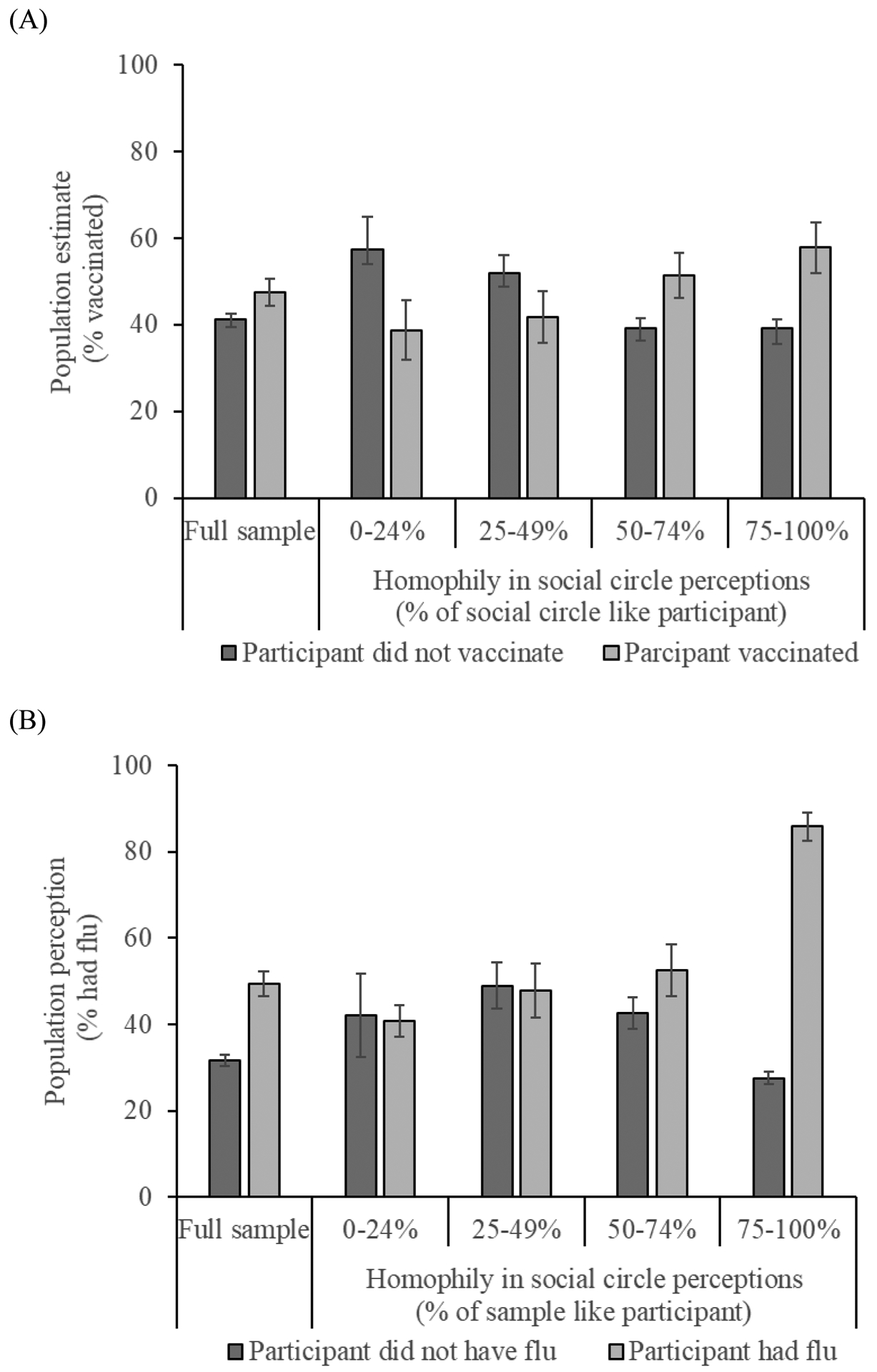

Figure 1:

Population estimates for (A) vaccination coverage and (B) flu prevalence, by own personal experience and ‘homophily’ of social circle.

Note: ‘False consensus’ is seen in higher population estimates among participants with (vs. without) the experience; ‘false uniqueness’ in the opposite pattern. The four categories of ‘homophily’ in social circle perceptions were created only for presentation purposes; associated analyses used the continuous variable. Error bars reflect one standard error.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics for participants with vs. without vaccination and flu experience

| Vaccination | Flu | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did vaccinate (N=154) | Did not vaccinate (N=197) | Had flu (N=71) | Did not have flu (N=280) | |

| Population estimates | ||||

| Mean (SD) population estimate of vaccine coverage | 47.47** (21.52) | 41.16 (20.58) | 41.63 (19.72) | 44.51 (21.56) |

| Mean (SD) population estimate of flu prevalence | 34.14 (25.10) | 35.99 (23.11) | 49.41*** (25.21) | 31.57 (22.31) |

| Social circle perceptions | ||||

| Mean (SD) perceived percent of social circle getting vaccinated in previous flu season | 49.79*** (26.70) | 27.07 (21.77) | 39.77 (27.27) | 36.35 (26.36) |

| Mean (SD) perceived percent of social circle getting flu in previous flu season | 21.15 (23.23) | 19.96 (23.97) | 33.39*** (29.32) | 17.21 (20.77) |

| Personal experiences | ||||

| Percent (N) who reported getting vaccinated in previous flu season | -- | -- | 47% (33) | 43% (121) |

| Percent (N) who reported getting flu in previous flu season | 21% (33) | 19% (38) | -- | -- |

| Vaccination intentions | ||||

| Mean (SD) percent chance of vaccinating this flu season | 87.83***(23.65) | 22.52 (31.31) | 53.07 (39.87) | 50.69 (43.78) |

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean (SD) age | 54.90*** (15.27) | 45.81 (14.08) | 45.51** (14.71) | 50.89 (15.25) |

| Percent (N) female | 51% (79) | 52% (102) | 54% (38) | 51% (143) |

| Percent (N) with college education | 47% (72) | 44% (86) | 39%* (28) | 46% (130) |

| Percent (N) white | 92% (141) | 86% (170) | 92% (65) | 88% (246) |

Note: Differences between groups were tested by t-tests for reported means, and by chi-square tests for reported percentages. CDC’s estimate for US 2010–11 vaccination coverage was 41%.17 CDC’s estimate for US 2010–11 flu prevalence was 9%, but based on a survey that only ran in January-April 2011.16

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Table 2:

Standardized estimates [and unstandardized estimates, standard errors] from linear regression models predicting population estimates.

| Vaccination | Flu | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | Model 2A | Model 3A | Model 1B | Model 2B | Model 3B | |

| Predictor variables | ||||||

| Personal experience (yes=1; no=0) | .16*** [6.81, 2.31] | -- | .03 [1.19, 2.44] | .26*** [15.56, 2.90] | -- | .17** [10.34, 2.79] |

| Social circle perception (0–100%) | -- | .32*** [.25, .04] | .31*** [.24, .04] | -- | .39*** [.39, .05] | .34*** [.35, .05] |

| Demographic control variables | ||||||

| Age | .00 [.00, .08] | .02 [.03, .07] | .02 [.02, .07] | −.24*** [−.37, .08] | −.21*** [−.33, .07] | −.19*** [−.30, .07] |

| Female | .08 [3.39, 2.21] | .08 [3.37, 2.12] | .08 [3.37, 2.12] | .13* [5.98, 2.32] | .12** [5.95, 2.20] | .12** [5.81, 2.16] |

| College education | −.20*** [−8.55, 2.22] | −.21*** [−8.75, 2.13] | −.21*** [−8.76, 2.13] | −.13** [−6.23, 2.33] | −.15** [−6.96, 2.21] | −.14** [−6.54, 2.18] |

| White | −.07 [−4.93, 3.52] | −.09 [−6.24, 3.38] | −.09 [−6.23, 3.38] | −.11* [−8.44, 3.70] | −.10* [−7.16, 3.50] | −.11* [−8.17, 3.45] |

| Model statistics | R2=.08 F(5, 350)=6.01*** | R2=.16 F(5, 350)=12.66*** | R2=.16 F(6, 350)=10.57*** | R2=.21 F(5, 350)=18.28*** | R2=.29 F(5, 350)=27.80*** | R2=.31 F(6, 350)=26.30*** |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Note: Interactions of social circle perceptions with personal experience and social circle characteristics appear in Table S3.

Table 3:

Standardized estimates [and unstandardized estimates, standard errors] from linear regression models predicting vaccination intentions.

| Overall sample | Participants who did vaccinate | Participants who did not vaccinate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | |||

| Social circle perception for vaccination (0–100%) | .32*** [.52, .09] | −.06 [−.06, .07] | .15*a [.19, .08] |

| Population estimate for vaccination (0–100%) | .05 [.11, .11] | .24** [.26, .08] | −.04 [−.06, .09] |

| Social circle perception for flu (0–100%) | .02 [.03, .10] | .03 [.04, .08] | .11 [.15, .09] |

| Population estimate for flu (0–100%) | .04 [.07, .10] | −.04 [−.04, .08] | .02 [.03, .09] |

| Demographic control variables | |||

| Age | .24*** [.03, .07] | .28 [.43, .11] | −.05 [−.10, .13] |

| Female | −.03 [−2.16, 4.27] | −.03 [−1.46, | .03 [1.72, 3.62] |

| College education | .01 [.42, 4.50] | .08 [4.18, 3.62 | −.04 [−2.78, 3.79] |

| White | −.02 [−2.17, 4.27] | .13 [10.88, 5.53] | −.06 [−4.94, 4.49] |

| Model statistics | R2=.20 F(9, 349)=9.45*** | R2=.18 F(9, 198)=4.71*** | R2=.05 F(9, 292)=1.79 |

Note: Adding interactions of own experience with population estimates and with social circle perceptions (each separately for vaccination and flu) in addition to own experiences to overall sample model revealed only a significant interaction of own experience x social circle perceptions for vaccination (β=−.09, B=−.15, se=.07, p<.001; seea).

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

significantly different from participants who did vaccinate.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics.

Table S1 shows descriptive statistics for invitees and participants. Our sample’s reported 2010–11 vaccination rate was 40%, and flu prevalence 21%. Participants’ average social circle perceptions were closer to these sample statistics than their average population estimates (37% vs. 44% for vaccination, 20% vs. 35% for flu). The Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimate for Americans’ 2010–11 vaccination coverage was 41%.17 CDCestimated US flu prevalence at 9%, but based on a survey that only ran in January-April 2011.16

False consensus

Participants who reported getting vaccinated in the previous flu season (vs. not) estimated greater population vaccine coverage (Figure 1A). Similarly, participants who reported getting flu (vs. not) estimated greater population flu prevalence (Figure 1B). Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for participants who got vaccinated and flu (vs. not).

Role of social circle perceptions.

For vaccination and flu, participants’ social circle perceptions were associated with population estimates and personal experiences (Table S4). Population estimates were predicted by social circle perceptions even after accounting for false consensus or relationships of population estimates with personal experiences (Table 2; Model 3A vs. 2A for vaccination; Model 3B vs. 2B for flu). Conclusions held when comparing dichotomized social circle perceptions with already dichotomized measures of personal experience (Table S2), and were unaffected by personal experiences or characteristics of social circle perceptions, with one exception (Table S3).

Less false consensus emerged among participants reporting fewer social contacts sharing their experience (Figure 1). Linear regressions predicting population estimates showed significant interactions between social circle homophily (or percent of social contacts like participants) and participants’ reported experiences, such that participants with less like-minded social circles weighed personal experience less when making population estimates (β=.70, B=.49, se=.09, p<.001 for vaccination; β=.57, B=.73, se=.10, p<.001 for flu). Estimated population vaccine coverage even showed ‘false uniqueness,’ such that participants reporting less like-minded social circles viewed the population as less like themselves (Figure 1A).

Vaccination intentions.

Reported vaccination intentions were correlated with population estimates and social circle perceptions for vaccination, but not for flu (Table S4). However, perceived social circle vaccine coverage was the sole independent predictor of vaccination intentions – especially among participants who indicated not having vaccinated in the previous flu season (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In a national flu survey, we found that population estimates for vaccination and flu rates were larger among participants reporting those experiences, which traditionally has been deemed false consensus.1 However, unlike what has traditionally been thought, population estimates seemed less informed by personal experiences than by social circle perceptions. These findings align with propositions that false consensus in population estimates may actually reflect selective exposure to peers with congruent characteristics.1,6,8 Furthermore, participants reporting less like-minded social circles showed less false consensus – and tended towards false uniqueness, or perceiving the population to be less like themselves. The same pattern occurred for vaccination and flu -- despite differences in controllability and prevalence.18,19

Moreover, perceived social circle vaccine coverage predicted vaccination intentions independent of population estimates, especially among participants who did not vaccinate in the previous flu-season. Individuals who do not vaccinate but perceive social contacts who vaccinate may become motivated to change their behavior. Indeed, people’s vaccination decisions appear sensitive to perceived peer social norms.12,20

One limitation is that we lacked information about actual characteristics of participants’ social contacts. However, perceived social circle characteristics are often more relevant than actual ones, for people’s judgments and decisions.21 Although false consensus errors affect surrogates’ predictions of peer preferences for medical treatments,22 people generally do have relatively accurate perceptions of their social circle’s characteristics.7,22,23 Here, participants’ social circle perceptions for vaccination and flu rates were similar to our overall sample’s statistics. The former also approached CDC estimates. Thus, people may reason with information they have about themselves and their social contacts.7,8,,24,25 Using social circle perceptions in addition to information about oneself can improve predictions about population-level outcomes.26

Yet, our findings suggest that tendencies towards selecting like-minded peers will exacerbate disagreements about population estimates – potentially promoting distrust in health messages opposing one’s views.3 Disagreements may be reduced by interventions that increase exposure to diverse others. Social network interventions also help to promote health behaviors.27

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The funding agreements ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Authors’ note: AP and RV were supported by the National Cancer Institute (R21CA157571) and the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (R01AI118705); WBB by the Swedish Foundation for the Humanities and Social Sciences Program on Science and Proven Experience and the National Institutes of Health (P30AG024962); MG by NIFA/USDA (2018-67023-27677) and NSF DRMS (1757211).

This research was inspired by the late Robyn Dawes. We thank Henrik Olsson for his comments, as well as participants of the meetings at which we presented our findings. This research was previously presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society in New Orleans LA (US), the 2019 annual meeting of the University of Southern California’s Roybal Center for Decision Making to Improve Health and Financial Independence in Old Age in Washington DC (US), and 2019 meetings on “Science and Proven Experience” organized by Lund University (Sweden).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ross L, Greene D, House P. The “false consensus effect:” An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J Exp Soc Psychol 1977;13:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannarini T, Roccato M, Russo S. The false consensus effect: A trigger of radicalization in local unwanted land uses conflicts? J Environ Psychol 2015:42;76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz A, Wirth W, Müller P. We are the people and you are the fake news: A social identity approach to populist and citizens’ false consensus and hostile media perceptions. Communication Research in press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krueger JI. From social projection to social behaviour. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2007;18:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks G, Miller N. Ten years of research on the false consensus effect: An empirical and theoretical review. Psychol Bull 1987;102:72–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitley BE. False consensus on sexual behavior among college women: Comparison of four theoretical explanations. J Sex Res 1998:35;206–214 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galesic M, Olsson H, Rieskamp J. Social sampling explains apparent biases in judgments of social environments. Psychol Sci 2012;23:1515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galesic M, Olsson H, Rieskamp J. A sampling model of social judgment. Psychol Rev 2018;125:363–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hertwig R, Pachur T, Kurzenhäuser S. (2005). Judgments of risk frequencies: tests of possible cognitive mechanisms. J of Exp Psychol Learn Mem and Cog 2005;31:621–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachur T, Hertwig R, Rieskamp J. Intuitive judgments of social statistics: How exhaustive does sampling need to be? J Exp Soc Psychol 2013;49:1059–77. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 2001;27;415–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker AM, Vardavas R, Marcum CS, Gidengil. Conscious consideration of herd immunity in influenza vaccination decisions. Am J Prev Health. 2013;45:118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Galesic M, Vardavas R. Reports of social circles’ and own vaccination behavior: A national longitudinal survey. Health Psychol. 2019; forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.RAND’s American Life Panel. https://www.rand.org/labor/alp.html

- 15.RAND’s American Life Panel, MS216. https://alpdata.rand.org/index.php?page=data&p=download&ft=paper&syid=216

- 16.Biggerstaff M, Jhung MA, Reed C, Fry AM, Balluz L, Finelli L. Influenza-like illness, the time to seek healthcare, and influenza antiviral receipt during the 2010–2011 influenza season - United States. J Infectious Diseases 2014;210:535–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). Final state-level influenza vaccination coverage estimates for the 2010–11 season-United States, National Immunization Survey and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, August 2010 through May 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage_1011estimates.htm

- 18.Alicke MD. Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985:49;1621–1630. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unwaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999:77; 1121–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Quinn SC, Kim KH, Musa D, Hillyard KM, Freimuth VS. The social ecological model as a framework for determinants of 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine uptake in the United States. Health Educ Behav 2011:39;229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prinstein MJ, Wang SS. False consensus and peer contagion: Examining discrepancies between perceptions and actual reported levels of friends’ deviant and health risk behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2005;33:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fagerlin A, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Houts RM. Projection in surrogate decisions about life-sustaining medical treatments. Health Psychol 2001:20;166–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nisbett RE, Kunda Z. Perception of social distributions. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985;48:297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawes RM (1989). Statistical criteria for establishing a truly false consensus effect. J Exp Soc Psychol 1989;25:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawtry RJ, Sutton RM., Sibley CG. Why wealthier people think people are wealthier, and why it matters: From social sampling to attitudes to redistribution. Psychol Sci 2015;26:1389–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galesic M, Bruine de Bruin W, Dumas M, Kapteyn A, Darling JE, Meijer E Asking about social circles improves election predictions. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2:187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: A critical review. Behav Med 2015:41;90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.