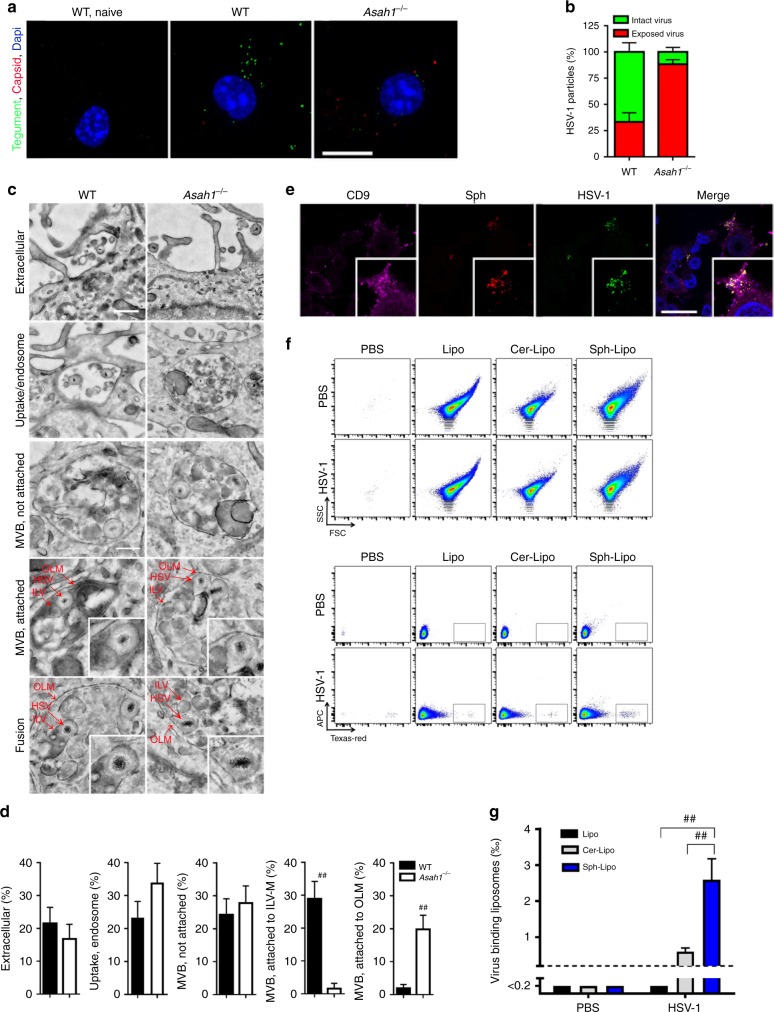

Fig. 5. Sphingosine-rich intraluminal vesicles trap HSV-1.

a, b Representative images (a) and quantification (b) of immunofluorescence from wild-type (WT) and Asah1−/− bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) incubated with HSV-1-VP16-GFP (multiplicity of infection [MOI] 30) for 30 min. Intact viral particles are visible through GFP-tagged tegument protein VP16 (green). Exposed capsids were stained with anti-VP5 (red, n = 17 images, one of two experiments is shown, scale bar 10 µm). c, d Representative electron microscopy images (c) and quantification (d) of WT and Asah1−/− BMDMs infected with HSV-1 (MOI 250) analyzed after 30 min (n = 68 WT images and n = 63 Asah1−/− images from three independent experiments; upper scale bar 400 nm, lower scale bar 200 nm, Mann-Whitney test). e Immunofluorescence of WT BMDMs, which were loaded with clickable ω-azido-sphingosine for 3 h, infected with HSV-1 (MOI 10) for 30 min and then stained for sphingosine, the intraluminal vesicle (ILV) marker CD9, HSV-1 anti-capsid and Hoechst (blue, n = 5, scale bar 20 µm). f, g Representative dot plots (f) and quantification (g) of control liposomes, ceramide-loaded liposomes and sphingosine-loaded liposomes that were incubated with fluorescently labeled HSV-1 for 10 min and then analyzed for HSV-1 binding in flow cytometry (n = 6, 2-way ANOVA [Tukey’s multiple comparison]). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, #p ≤ 0.001, ##p ≤ 0.0001.