Abstract

Co-delivery of therapeutic agents and small interfering RNA (siRNA) can be achieved by a suitable nanovehicle. In this work, the solubility and bioavailability of curcumin (Cur) were enhanced by entrapment in a polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer, and a polyplex was formed by grafting Bcl-2 siRNA onto the surface amine groups to produce PAMAM-Cur/Bcl-2 siRNA nanoparticles (NPs). The synthesized polyplex NPs had a particle size of ~180 nm, and high Cur loading content of ~82 wt%. Moreover, the PAMAM-Cur/Bcl-2 siRNA NPs showed more effective cellular uptake, and higher inhibition of tumor cell proliferation compared to PAMAM-Cur nanoformulation and free Cur, due to the combined effect of co-delivery of Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA. The newly described PAMAM-Cur/Bcl-2 siRNA polyplex NPs could be a promising co-delivery nanovehicle.

Keywords: Curcumin, Bcl-2 siRNA, PAMAM dendrimer, Co-delivery, HeLa cancer cells, Nanoparticles

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is common among women worldwide, and standard treatments include cisplatin chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy [1]. However the poor pharmacokinetics of most anticancer agents, and the occurrence of dose-limiting side-effects, often leads to treatment failure [2]. The disadvantages of cytotoxic chemotherapy have increased interest in traditional herbal medicine and natural products in the modern world as well as the ancient world [3]. Curcumin (Cur) is a natural phenolic compound found in the spice turmeric, that is derived from the roots of the Curcumina longa plant [4–6]. Cur has beneficial properties such as a high anti-proliferative effect and efficient induction of apoptosis against breast, cervical, and melanoma cancers caused by its interaction with a variety of molecules such as growth factors, enzymes, carrier proteins, metal ions, tumor suppressors, transcription factors, oncoproteins and nucleic acids [7]. Moreover, its low toxicity towards normal cells and tissues has attracted much attention in cancer therapy [8, 9]. However, the clinical application of Cur suffers from limitations due to its poor water solubility and instability, which leads to low bioavailability of Cur in cancer cells. Efforts towards increasing the therapeutic efficacy of Cur have been accomplished by different methods [10, 11]. For example, NP-based drug delivery systems have become a promising approach to overcome the limitations of pure Cur. Thus, physical encapsulation of Cur inside NPs can enhance the water solubility of Cur, increase the biocompatibility, protect it from degradation, maintain a long blood circulation time, and encourage accumulation of Cur in tumor tissues due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [9, 12].

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) is a synthetic double-stranded RNA composed of 21–23 nucleotides that has been demonstrated a powerful gene-silencing capability with potential as a new therapeutic method for cancer treatment. However, siRNA is unable to cross cell membranes and be delivered to the desired site of action (cytoplasm) owing to some inescapable problems including degradation by nucleases, rapid capture by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), and inefficient endosomal escape [10, 13, 14]. In order to overcome these barriers and achieve targeted delivery of siRNA, NP-based delivery systems have been designed to enable siRNA administration and transfection. In these NPs, the negatively charged siRNA is generally complexed with various cationic polymers via electrostatic interactions [10, 15]. These complexes or polyplexes composed of NPs containing siRNA should be stable enough to survive in the blood circulation until extravasation occurs across the vascular endothelium in the tumor, and diffusion across the extracellular matrix to reach the cancer cells [15, 16].

However, siRNA only targets specific genes, for instance, those involved in avoiding apoptosis or promoting cell division, and therefore cannot be used as a single therapy owing to the multiple gene dysregulations commonly found in cancer [17, 18]. The co-delivery of chemotherapeutic agents together with siRNA, using a single nano-delivery system could exert synergistic effects due to simultaneous cytotoxicity and suppression of gene expression [10, 16]. Among the different types of vectors that have been used as dual delivery systems, cationic dendrimers and especially amine-terminated polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers belongs have been widely investigated as carriers [19]. The advantages of PAMAM dendrimers include a high density of surface groups, controlled drug release, spherical shape, low polydispersity, and good water solubility, make them good candidates for simultaneous delivery of genes and drugs into tumor cells [19, 20]. PAMAM dendrimers possess a relatively hydrophobic interior that allows physical encapsulation of hydrophobic chemotherapeutic agents to improve their water solubility and bioavailability, and also a hydrophilic surface with free amine groups that allows both grafting siRNA onto the surface, and facilitating endosomal escape by means of the proton sponge effect [20, 21]. Thereby both siRNA and chemotherapy drugs can be delivered into the cytoplasm where they are needed [9, 16].

In the present study, a PAMAM dendrimer generation four (G4) was used for the co-delivery of a siRNA molecule targeting the Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic gene, and the anticancer Cur compound into human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cells. Cur was entrapped inside the PAMAM dendrimer cavity to make PAMAM-Cur formulation followed by complex formation with Bcl-2 siRNA through electrostatic interactions.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Materials

The amine-terminated G4 PAMAM dendrimer built on an EDTA core with an average molecular weight of 14ˏ215, curcumin, and 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The HeLa cell line was purchased from the cell bank of Iran (Pasteur Institute). RPMI-1640 cell culture media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin-ethylenediamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) solution and penicillin/streptomycin were from Gibco Co (Dublin, Ireland). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was from Merck-Co. FITC labeled Bcl-2 siRNA (sense strand: 5ʼGGAUCCAGGAUAACGGAGGTT-3ʼ, antisense strand: 5’ CCUCCGUUAUCCUGGAUCCTT-3’), were supplied by Santacruz (USA). AnnexinV-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit was purchased from Oncogene Research Products (San Diego, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Curcumin-loaded PAMAM dendrimer

Different weight/weight ratios of PAMAM-Cur ranging from 8:1 to 1:1 were tested to optimize the appropriate proportion of 1:1 as previously described [22, 23]. Briefly, 1 mL Cur dissolved in methanol (1 mg/mL) was added drop-wise into 1 mL of PAMAM dendrimer solution in methanol (1 mg/mL) and 2 mL of PBS. The mixture solution was vigorously stirred for 2 days to allow the encapsulation of Cur inside the cavity of PAMAM. The methanol was removed using a rotary evaporator leaving a PBS suspension. The PAMAM-Cur mixture was centrifuged (5000 rpm for 15 min in 4 ◦C) to remove the precipitate of non-complexed free Cur that is insoluble in PBS. The precipitate was collected and dissolved in 1 mL methanol and the amount of unloaded drug was determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy. The supernatant was protected from light and stored at 4 ◦C.

2.3. Drug loading

The entrapment efficiency (EE) and loading capacity (LC) of the PAMAM-Cur formulation was investigated by measuring the concentration of free Cur by checking absorbance spectra by UV-Vis spectrophotometry at 430 nm (λ max of Cur). The percentage of EE and LC were calculated according to the following equations, respectively [24, 25].

| Equ. 1 |

| Equ. 2 |

2.4. siRNA binding ability

The binding and condensation capacity of PAMAM-Cur with siRNA was studied by a gel retardation assay. The FITC labeled Bcl-2 siRNA polyplexes were formed by gently mixing the carrier and siRNA at different nitrogen/phosphate (N/P) mass ratios from 1 to 50 in DEPC water and incubated at room temperature for 30 min for complete complex formation. Then electrophoresis was carried out on 2% (w/v) agarose gel with SYBR safe stain at a voltage of 70 V for 40 min in Tris-acetate-EDTA running buffer solution, with the naked siRNA serving as a reference. The retardation of siRNA mobility was visualized by ultraviolet light and gel photography [16].

2.5. Physicochemical characterization of nanoparticles

The hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of the PAMAM-Cur formulation and PAMAM before and after siRNA-loading at a N/P ratio of 20:1 were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, U.K.) and the results were evaluated by means ± standard deviation (SD). To determine Cur entrapment in the system (PAMAM-Cur) UV-vis absorption spectra measurements of free Cur, PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur were conducted [26].

2.6. Curcumin release from PAMAM-Curcumin complex

To determine the amount of Cur released, the dialysis bag method using phosphate buffered saline (pH 5.4 and 7.4) was used. PAMAM-Cur (containing 1 mg/mL Cur) complex was dissolved in PBS (5 mL) in bags with a molecular weight cut-off of 10 kDa. The bags were incubated at 37 °C on a horizontal shaker (200 rpm) in 50 mL PBS which allowed the free Cur molecules to diffuse into the medium. Samples (500 μL) were taken at selected incubation times for 3 days and were replenished with the same volume of fresh PBS. The quantity of released Cur was determined using HPLC analysis. The samples containing released Cur were extracted with chloroform (1:1 vol ratio) and then dissolved in 50 μL methanol before injection into a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatograph equipped with Cecil 1100 series UV detector and mobile phase composition of 75% acetonitrile and 25% water containing 5% acetic acid at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and a detection wavelength of 430 nm. The amount of payload release was determined using an experimentally determined standard curve (linear range; 0.1–50 μg/mL) [27–29].

2.7. Light stability profile of Curcumin and PAMAM-Curcumin

Free Cur or PAMAM-Cur nanoformulation (1 mg/ml) were dissolved in 4 ml PBS and were exposed to a direct stream of light over various time intervals from 1 to 72 hours in order to compare the photostability of Cur encapsulated inside PAMAM dendrimers and free Cur by measuring the degraded byproducts and the reduction in the absorption peaks of Cur and PAMAM-Cur. The samples were measured by HPLC to calculate the remaining amount of each sample until 72 h [30].

2.8. Cell culture and cell viability assay

HeLa cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing antibiotics (100 units/mL penicillin and 50 units/mL streptomycin) and fetal bovine serum (10%), in an atmosphere with a relative humidity of 95% and CO2 concentration of 5%. The cytotoxicity effects of different formulations against HeLa cancer cells was measured by MTT assay. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1×104 cells/well) in 200 μL medium and subsequently cultured overnight. Different groups containing different concentrations of Cur, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA ranging from 5 to 40 μg/mL at N/P ratios of 20:1 with the serum-free medium were added into the wells and incubated for 6 h. After that, the culture medium was replaced by complete culture media and cells were incubated for another 24 h or 48 h. At the end of the incubation time, 50 μL of prepared MTT solution in PBS buffer (2 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for another 4 h. Then, 200 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals formed by the viable cells. In the end, the spectrophotometric plate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc, Vermont, USA) was used for UV absorbance measurements at 570 nm. All experiments were repeated three times [31, 32].

2.9. Intracellular trafficking

2.9.1. Fluorescence microscopy

Intracellular translocation of free Cur and other treated groups contained Cur that was mentioned before visualized by fluorescence microscopy. A 12-well plate was used to seed HeLa cells with a density of 1×105 cells per well. Cells grew in 1 mL supplemented cell culture medium overnight. After that, the culture medium was replaced with 1 mL antibiotic and serum-free medium, which contained Cur at a concentration of 20 μg/mL and incubated for 6 h. Subsequently, the medium was removed, and cells were washed carefully with PBS twice and replaced with 1 mL fresh medium and observed using a fluorescence microscope to observe the effect of the designed delivery system. The fluorescence signals of the Cur and FITC labeled Bcl-2 siRNA were excited at 430 nm and 495 nm and the emission measured at 470 nm and 520 nm, respectively [33].

2.9.2. Flow cytometry

Characterization of the cellular uptake of PAMAM-Cur/siRNA, PAMAM/siRNA polyplexes, PAMAM-Cur and free Cur groups was conducted by flow cytometry. The HeLa cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in complete culture media containing 10% FBS and incubated until they reached 70% confluency. After removing the medium, cells were incubated in fresh medium with different concentrations of Cur ranging from 5 to 40 μg/mL at N/P:20 for 6h. Thereafter, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were rinsed with PBS, trypsinized and washed with PBS. The FACScan analysis was used to obtain the mean value of fluorescence [34].

2.10. Apoptosis assay

For apoptosis analysis, HeLa cells were seeded in 6 well plates (100,000 cells/well) and incubated for 24h. After that, the medium was replaced with the above-mentioned formulations at a concentration equivalent to 20 μg/ml Cur. After 48 h of treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinization and stained using Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit, which was used to measure apoptosis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software [32, 35].

2.11. DAPI staining assay

DAPI staining assay was carried out to observe apoptotic cells. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates and treated with different treatment groups based on 20 μg/ml Cur concentration for 48 h. After treatment, the HeLa cells were washed with PBS and were fixed by paraformaldehyde (PFA; 4%) for 2h and washed with PBS. Then, the cells were permeabilized by 1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, washed with PBS again, and eventually stained with 1 μg/mL of DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) stain for 15 min. Morphological changes in apoptotic nuclei were observed and photographed under the fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence signal of the DAPI staining of nuclei was excited at 340 nm and detected at 480–500 nm [36].

2.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) the GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, CA, USA). The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and n showing the number of repeats. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculation of effect size was carried out using equal 3 in which M1 is means of either control or effect size of this study, while M2 the means of experiment or effect size of cited studies. Meanwhile, the difference between 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8% is considered small, medium and large, respectively.

| 3 |

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of Curcumin-loaded PAMAM dendrimer

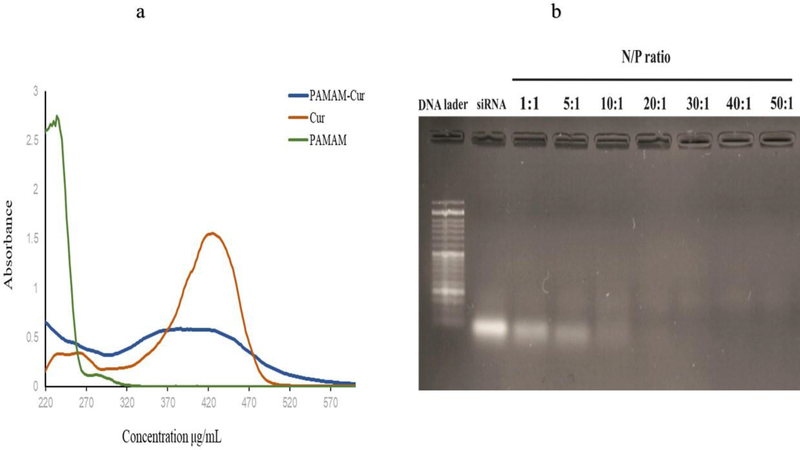

Cur was entrapped in the PAMAM dendrimer with a ratio of 1:1 (w/w) in PBS and the formation of PAMAM-Cur NPs was proved by the typical absorbance peak of Cur at 430 nm. Based on the obtained result of UV–Vis spectra of Cur and PAMAM (Fig. 1a) the absorption spectra of Cur dissolved in methanol, PAMAM and PAMAM-Cur formulations solubilized in PBS, were obviously different. Therefore, a strong peak at 430 nm with a shoulder at ~370 nm characterized the absorbance curves of Cur alone and PAMAM-Cur, respectively. In other words, solubilization of Cur by entering into the pockets of PAMAM led to enhancement of Cur absorbance with a redshift compared to the same concentration of free Cur [37]. After characterization of PAMAM-Cur formation, the LC and EE of the PAMAM-Cur nanoformulation were calculated, which was around 82 %, and it is attributed to choosing the 1:1 (w/w) ratio of Curcumin and PAMAM dendrimer.

Fig 1.

Characterization based on (a) UV–vis spectra of Cur, PAMAM and PAMAM-Cur; (b) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PAMAM-Cur/siRNA polyplex at different N/P ratios.

3.2. siRNA binding ability

The complex formation of the PAMAM-Cur formulation with siRNA was studied by a gel retardation assay. As shown in Fig.1b, at different N/P ratios, siRNA retardation was gradually observed starting at N/P ratio of 10, but complete condensation of siRNA and maximum retardation was observed at N/P ratios of >20, which indicated the appropriate siRNA binding and packaging capability of PAMAM-Cur.

3.3. Characterization of PAMAM dendrimer derivatives

The hydrodynamic size and zeta-potential at N/P ratios of 20:1 were determined by Zetasizer (Fig. 2). As shown in Table. 1, increasing hydrodynamic sizes were observed for empty PAMAM compared to PAMAM-Cur/siRNA, while the zeta-potential value showed a decreasing tendency. The mean particle size was found to be 16, 92.86, 120, 180 nm and the zeta potential was +5.25, 1.25, −35 and −48 mV for PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA, respectively. Besides, the nanoparticles showed a low polydispersity index (PDI≤0.60), which indicates a relatively narrow size distribution. Nanoparticles with a PDI value > 0.7 are considered to have a very broad distribution of particle size [38].

Fig 2.

Particle size distribution and Zeta potential of PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA.

Table 1.

Particle size and zeta potential of blank PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA (n = 3).

| Samples | Size ± SD (nm) | ζ potential ± SD (mv) | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAMAM-Cur/siRNA N/P=20 | 180.4 ± 84.60 | −39.3 ± 22.0 | 0.6 |

| PAMAM/siRNA N/P=20 | 120.3 ± 25.70 | −28.9 ± 8.68 | 0.6 |

| PAMAM -Cur | 92.86 ± 27.70 | 5.25±5.82 | 0.3 |

| PAMAM | 16 ± 7.535 | 6.59 ± 6.36 | 0.3 |

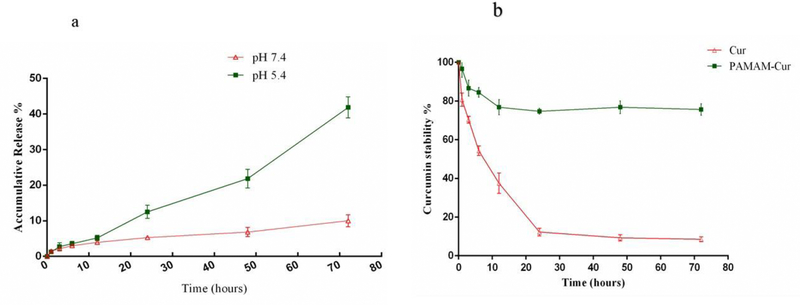

3.4. In vitro release studies

The in vitro release profile of Cur from the dendrimer formulation was investigated by a dialysis bag method at pH = 5.4 and pH = 7.4 for 72 h in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) to simulate Cur release under an acidic tumor environment and at physiological conditions, respectively. It is evident from Fig. 3a that a biphasic burst release occurred. During the initial period, until 10 h <5% of Cur was released at both investigated pH values, followed by a longer release period only at pH 5.4 to about 40% in 72 h, while at pH 7.4 only 10% of Cur was released in the external medium over 72 h. The initial equal release at both pH 7.4 and 5.4 occurred due to the loss of superficial Cur from the NP surface, which was followed by a sustained release of the drug only at pH 5.4 [12].

Fig 3.

(a) Cur release from PAMAM-Cur nano formulation in PBS (pH 7.4, pH 5.4) at 37 °C and (b) HPLC analysis of free Cur and PAMAM-Cur after exposing to light. Error bars represent SD.

3.5. Light stability testing

As can be seen in Fig. 3b, the absorption of free Cur dissolved in PBS was gradually reduced from 100% to 10% at the end of 72 hours, whereas the PAMAM-Cur complex was protected from photodegradation and showed higher photostability of the encapsulated Cur. There was only a 25% drop in the absorption peak of PAMAM-Cur complex during the mentioned time intervals [30].

3.6. In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Simultaneous delivery of Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA was evaluated for their synergistic anticancer properties in HeLa cells via an in vitro MTT cytotoxicity assay, which measures the cell survival rate and reflects their growth states. HeLa cells were incubated with Cur, PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA at various concentrations ranging from 5 to 40 μg/mL of Cur for 24 and 48h. As shown in Fig. 4a and 4b, Cur and PAMAM-Cur demonstrated inhibition of cell growth in a concentration and time-dependent manner upon increasing the drug concentration for 24 and 48 h incubation, but in the PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA groups, dose-dependent inhibition was seen only after 48 h treatment. The results indicated that PAMAM-Cur/siRNA produced the lowest cell viability compared to other formulations and the free drug. It was found that IC50 value of pure Cur dissolved in PBS after 24 and 48h treatment was above 40 μg/mL, and for PAMAM-Cur and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA the IC50 values were 36 and 33 μg/mL after 24 h, and 33 and 20 μg/mL after 48h, respectively. Empty PAMAM (drugfree) which has been used as a gene/drug delivery system at doses as high as 100 μg/mL displayed no reduction in cell viability and showed good biocompatibility.

Fig 4.

In vitro cytotoxicity of free Cur, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA on HeLa cancer cells based on Cur concentrations of 5 to 40 μg/mL for 24 (a) and 48 h (b). *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Untreated cells served as a negative control (n = 3).

3.7. In vitro cellular uptake studies

3.7.1. Cellular uptake by fluorescent microscopy

Fluorescence microscopic studies were employed to evaluate concentration dependent uptake of PAMAM-Cur/siRNA, PAMAM/siRNA, and PAMAM-Cur into HeLa cells. As can be seen in Fig. 5a, with increasing concentration, the green fluorescence intensity was enhanced in the groups and both PAMAM-Cur/siRNA and PAMAM/siRNA complexes (at the concentration of 40 μg/mL of PAMAM dendrimer) exhibited higher internalization of Bcl-2 siRNA.

Fig 5.

(a) Cellular internalization by means of fluorescence microscopy; (b) flow cytometry histograms and geometric mean fluorescence graphs following 4 h incubation at 37 °C with various concentrations ranging from 5 to 40 μg/mL of Cur in N/P ratio of 20.

3.7.2. Cellular uptake by flow cytometry

Quantitative evaluation of intracellular uptake of free Cur and Cur loaded PAMAM dendrimer formulations was carried out using flow cytometry. The inherent fluorescence of Cur and FITC labeled siRNA was used to follow intracellular uptake into HeLa cells. After 6 hours of incubation, free Cur did not show any detectable fluorescence inside HeLa cells (data not shown). As seen in Fig. 5b, the mean fluorescence intensity of PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA complexes was much stronger than that of the PAMAM-Cur formulation at the same concentration. This was due to the stronger fluorescence in this window from FITC-siRNA compared to that from Cur. The cellular uptake was concentration dependent over 5 to 40 μg/mL PAMAM dendrimer. The fractions of FITC-positive cells with concentrations of 5, 10, 20 and 40 μg/mL of PAMAM-Cur were 3.45%, 8.77%, 18.8% and 34.82%. PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA displayed 4.22%, 25.9%, 66.1%, 88% and 9.34%, 37.2%, 81.1% and 89.7%, respectively. These results suggest that PAMAM dendrimer-based systems could facilitate the efficient delivery of both Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA into HeLa cancer cells.

3.8. Annexin V-FITC apoptosis

To examine the stimulation of apoptosis, HeLa cells were treated with various formulations of Cur with a concentration of 20 μg/mL of Cur for 48 h. Empty PAMAM was also evaluated for any stimulation of apoptosis (Fig. 6a). The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated by flow cytometry (FACScan) using Annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) staining. HeLa cells that were not stained by either Annexin VFITC and PI were categorized as living, Annexin V-FITC positive but PI negative cells were categorized as early apoptotic cells. Double positive Annexin V-FITC and PI positive cells were classified as late apoptotic cells. PI positive, Annexin V negative staining cells were classified as necrotic cells. The morphology of both negative control and empty PAMAM treated cells remained unaffected and these cells were undamaged, which indicated its safety in drug/gene delivery systems. Some apoptotic cell population appeared in all the treated groups; however, the percent of apoptotic cells varied among the treatments. As shown in Fig. 6b, the percentages of apoptotic cells in free Cur, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA groups were 14.89%, 46.77%, 37.69%, and 73.66% respectively. PAMAM-Cur/siRNA treated cells showed the highest apoptosis fraction compared to the other treatment groups.

Fig 6.

(a) Apoptosis histograms and (b) apoptosis percentage of HeLa cancer cells measured by flow cytometry using AnnexinV/PI after 48 h incubation with free Cur, empty PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA based on Cur concentration of 20 μg/mL. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Untreated cells served as a negative control (n = 3).

3.9. DAPI staining analysis for morphological changes of the nucleus

The presence of condensed and fragmented DNA in the apoptotic cells was evaluated by fluorescence microscopic analysis of DAPI stained HeLa cells. Microscopic images of the DAPI-stained cells after 48h exposure to IC50 concentration of free Cur, empty PAMAM, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA and 5% DMSO (positive control) are shown in Fig. 7. The lack of toxicity of empty PAMAM dendrimer on the cells was further confirmed by DAPI staining, and the nucleus of the untreated control cells remained intact. Typical morphological markers of apoptosis such as nuclear shrinkage, fragmentation and condensation or remodeling in the chromatin and DNA rings were predominantly observed in all positive control, PAMAM-Cur, PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA treated groups. The morphological changes in the nucleus of cells treated with PAMAM-Cur/siRNA were more pronounced than that of the other groups. PAMAM/siRNA polyplex displayed fewer abnormal morphological features compared to PAMAM-Cur/siRNA polyplex and PAMAM-Cur, but the highest morphological change in the nucleus was seen in PAMAM-Cur/siRNA polyplex treated group.

Fig 7.

Light and fluorescence microscopy images of HeLa cells stained with DAPI. The arrows show chromatin and DNA fragmentation with PAMAM-Cur and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA.

4. Discussion

Apoptosis is a genetically determined programmed cell death and plays a crucial function in cervical cancer development and treatment [39, 40]. Apoptosis is carried out by two main pathways: caspasedependent (extrinsic) and caspase-independent (intrinsic) pathways [40, 41]. Alterations in the normal operation of the extrinsic and intrinsic mediated apoptotic signaling pathways result in malignancies and resistance to standard chemotherapeutic agents [19, 42]. On the other hand, regulation of the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways is carried out by proteins that are over-expressed in cancer cells [43]. Both Bcl-2 and Bax are important members of the pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, and equilibrium between them inside the mitochondria regulates the apoptotic pathways [40, 44]. Over-expression of Bcl-2 increases tumorigenesis by allowing cancer cells to avoid undergoing apoptosis [20, 44, 45]. Hence, inhibition of the expression levels of Bcl-2 can restore the ability of the cancer cells to undergo apoptosis and thereby facilitate cancer therapy. Suppression of the Bcl-2 gene based on siRNA technique has been used to increase the apoptosis of cancer cells [19, 20].

Cur is a traditional medicine that down-regulates expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, XIAP and survivin, and conversely up-regulates expression of Bax, Bak, PUMA, Noxa and Bim at both mRNA and protein levels in cervical cancer cells [10].

PAMAM dendrimer is one of the most useful nanocarriers that have been tested in biological systems and leads to passive accumulation in tumor tissues through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect due to its nano-size scale [19, 20, 44]. The application of nanodelivery systems for payload release under physiological conditions is known as passive delivery and can be specific for tumors [46, 47]. Therefore, to improve the combination effect of Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA delivered to cancer cells, a PAMAM dendrimer nanocarrier was used to maximize the induction of apoptosis. The percent of EE and DL in the PAMAM-Cur nanoformulation were determined by calculating the amount of the non-complexed free Cur by UV–Vis spectrophotometry at 430 nm. Besides, UV-vis spectra demonstrated that the absorption spectra of free Cur and PAMAM-Cur nanoformulation were obviously different [37]. In order to choose an optimal N/P ratio for Bcl-2 siRNA loading, various N/P ratios were evaluated based on complex formation between Bcl-2 siRNA and PAMAM-Cur by agarose gel electrophoresis [48].

The electrostatic interactions formed a complex between siRNA and the surface of cationic PAMAM dendrimers, reducing the negative charge of the nucleic acids, which led to reduced mobility in the electric field [15]. Hence, the retardation of siRNA mobility in gel electrophoresis can be considered as a criterion for PAMAM-Cur complexation with Bcl-2 siRNA [13, 16]. The data showed that the PAMAM-Cur complex could not retard Bcl-2 siRNA mobility completely at low N/P ratios, but, when the N/P ratios increased up to 50, effective retardation of Bcl-2 siRNA migration appeared in the agarose gel. The nanoformulations were analyzed for size distribution and surface charge by DLS. In order to strike a balance between efficient cell transfection and possible cytotoxicity, an N/P ratio of 20:1 was chosen for the experiments. The results demonstrated that PAMAM dendrimer formulations possessed the desired size range with a narrow size distribution profile (PDI). Compared to empty PAMAM and PAMAM-Cur, both PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA showed an increase in the size and a decrease in the zeta potential owing to conjugation of siRNA on the surface of the PAMAM dendrimer [49]. In other words, masking the cationic surface charge of PAMAM dendrimer due to grafting of the negatively charged siRNA allowed reduction of the systemic toxicity and fewer adverse side effects [15]. Compared to the PAMAM-Cur complex, empty PAMAM could condense siRNA in a much tighter state. The phenomenon is probably attributed to a more opened structure of the PAMAM dendrimer after loading of Cur inside its cavities. Additionally, the increase in size of the PAMAM-Cur after encapsulation with Cur, in comparison with empty PAMAM maybe because of agglomeration of the complex during the preparation process, which means a larger hydrodynamic size. Besides, the increase in hydrodynamic size of the PAMAM-Cur nanoformulation proved that Cur was successfully loaded into PAMAM-Cur nanoparticles [16]. According to the release data, the first point to notice is that entrapment of Cur into the dendrimer cavity resulted in sustained release of Cur in the acidic environment of cancer cells. The interior tertiary amine groups of the dendrimer at the acidic pH of endosomes or lysosomes inside tumor cells undergo protonation, which causes an “extended conformation” of the dendrimer, repulsion between charges, diffusion and erosion of Cur from the swollen nanopolymer, and release into the cytosol by means of the proton sponge effect [10]. By contrast, shrinkage of dendrimer, which limits the swelling behavior of PAMAM and also causes collapse of the dendrimer occurs at alkaline pH by deprotonation of the tertiary amines, leading to poor release of Cur from the nanoformulation. Therefore, the results showed that the release rate of Cur from PAMAM-Cur was significantly dependent on the pH value. On the other hand, Cur is extremely sensitive to photolysis, and continuous exposure to light leads to degradation and loss of its biological activity. However, encapsulation of Cur in the PAMAM dendrimer, not only increased the Cur solubility, but protected the Cur from photo destruction. The results indicated that only a quarter of encapsulate Cur was photodegraded, while three quarters remained intact, confirming the potential of PAMAM dendrimer nanoparticles to enhance the stability of Cur in the presence of light [30]. The enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity results of PAMAM-Cur in comparison with free Cur might be related to the increased stability and solubility of Cur in PAMAM resulting in better Cur uptake via a passive diffusion mechanism [37]. The antiproliferative activity of the PAMAM-Cur/siRNA complex was higher than that of PAMAM-Cur. This suggests that PAMAM-Cur in combination with Bcl-2 siRNA produces an overall more effective anti-cancer agent, especially for stimulation of apoptotic signaling pathways. In addition, it was obvious that the cytotoxicity of PAMAM-Cur was slightly lower than for free Cur after 24h of treatment, which was possible because free Cur could better enter cells by rapid diffusion, while Cur needs to be released from PAMAM-Cur in a controlled and sustained manner for a long-term after the internalization. Hence, the anticancer efficiency of PAMAM-Cur could be improved with the extended drug release time. In addition, empty PAMAM displayed only slight cytotoxicity.

Moreover, the study of the cellular uptake of PAMAM/siRNA and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA polyplex was accomplished by FITC labeled Bcl-2 siRNA. The high uptake of the polyplex may be attributed to efficient internalization and delivery of siRNA into the cytosol. The cellular uptake of PAMAM-Cur and free Cur can be measured by the intrinsically fluorescent properties of Cur without using additional markers. These two agents were dispersed in PBS, which showed that PAMAM-Cur was stably dispersed and its Cur content could be visualized by fluorescence microscopy, while the free Cur began to precipitate after dispersion, and crystals formed with different sizes. Therefore, free Cur did not show any detectable fluorescence inside the cells suggesting that the NPs could improve drug incorporation into the cells by improving water solubility. Cellular internalization was further confirmed by flow cytometry.

Based on the results, intracellular internalization of PAMAM-Cur/siRNA was higher compared to PAMAM-Cur and PAMAM/siRNA; hence, improved therapeutic efficacy of PAMAM-Cur/siRNA could result from simultaneous delivery of Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA into HeLa cells. Also, the merged images demonstrated that Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA-loaded PAMAM dendrimer were localized in the cytoplasm of HeLa cells. The uptake data agreed with the apoptosis data and indicated that the co-delivery system of Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA could lead to more effective cell apoptosis compared to single Cur or siRNA delivery. This was attributed to the cooperative anticancer effects of Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA by which Bcl-2 siRNA and Cur at the same time suppressed the expression of the key apoptosis inhibitor, Bcl-2 in HeLa cells [20]. In addition, the nuclear morphological changes were evaluated using DAPI confirming the superiority of the PAMAM-Cur/siRNA polyplex to inhibit Bcl-2 and trigger apoptosis in the treated cells. Finally, it should be stated that since we did not have facility to carry out in vivo evaluation of the fabricated nanosystems, we report here some other in vivo studies. Sun et al evaluated therapeutic effect of doxorubicin (DOX) and BCL-2 siRNA delivered simultaneously using a triblock copolymer of poly (ethylene glycol)-block-poly(L-lysine)-block-poly-aspartic acid (PEG-PLL-PAsp) as a nanocarrier. Their in vitro results demonstrated that neither free DOX nor D/SCR-CP showed significant anticancer activity, while D/siR-CP was cytotoxic due to downregulation of the anti-apoptotic gene. BCL-2 not only sensitized cancer cells to DOX, but also exhibited the highest killing of cancer cells based on the synergistic effects of both siRNA and DOX. Moreover, the nanoparticles facilitated delivery of DOX and siRNA into HepG2/ADM cells. The effect size for the MTT assay, apoptosis and in vitro release assays varied from 0.7% to 19%. This was comparable to the effect size of the present study and the difference in effect sizes for both the studies was small (0.2) for MTT assay and medium (0.4) for the apoptosis test. Following in vitro assessment prepared DOX-siRNA-PEG-PLL-PAsp complex was intravenously injected into BALB/c nude mice bearing a HepG2/ADM xenograft tumor. The in vivo results showed that tumor size in mice treated with a single agent (either DOX or Bcl-2 siRNA) just showed a slight decrease, whereas the combined nano encapsulated BCl-2 siRNA plus DOX at the same dose caused a significant reduction in tumor size due to the synergistic effect of the dual complex. Furthermore, monitoring mouse body weight and cardiotoxicity was conducted to investigate potential toxicity of the various agents. According to the results, the highest weight loss and most cardiotoxicity were observed in mice that received free DOX, while mice treated with DOX-siRNA-PEG-PLL-PAsp maintained their body weight and showed no significant changes in the myocardial fibers [16]. In another study, Alibolandi and colleagues used Cur-loaded PAMAM dendrimers conjugated with carboxylated polyethylene glycol (PEG), an aptamer (MUC-1), and gold nanoparticles (Au) to evaluate the theranostic impact of the complex in comparison with free Cur. They reported that Apt-PEG-AuPAMAM-CUR showed higher fluorescence intensity than free Cur. Regarding the effect size, it was estimated to be from 0.04 to 1.47% in the MTT test. When compared with the effect size of the present study, which was from 0.24% (small) to 2.67% (large) when the IC50 of blank Cur was compared with Cur loaded inside PAMAM dendrimer. Besides, Apt-PEG-AuPAMAM-CUR complex caused more cytotoxicity compared to blank Cur. Based on in vivo analyses, C26 tumor-bearing mice (BALB/c female mice) treated with Apt-PEG-AuPAMAM-CUR, which displayed the highest anticancer activity according to survival rate, body weight change and amount of tumor growth in opposition to free Cur. They also found that CUR encapsulated inside PAMAM dendrimers prolonged the CUR blood circulation half-life. The safety of the complex was assessed by measuring both body weight and mouse survival rate, in groups that were treated with free CUR or AuPAMAM-CUR for 30 days. The Apt-PEG-AuPAMAM-CUR treatment did not lead to any obvious loss in mouse body weight [4].

Chen et al in 2019 reported a system using a PAMAM-OH derivative (PAMSPF) as a carrier for co-delivery of p53 plasmid and MDM2 inhibitor (RG7388) simultaneously into MDA-MB-435, MCF-7/WT and MCF-7/S cancer cells. They found synergistic anti-tumor effects of PAMSPF/p53/RG using in vitro studies, meaauring inhibition of proliferation, cell cycle arrest, and induction of apoptosis compared to single administration of either p53 or RG7388 alone. Moreover, the effect size measured for the cellular uptake with a N/P of 16 was between 20% and 35% which was comparable with the effect size of the cellular uptake in the present study (16% - 40%) in three cancer cell lines. The differences between the effect sizes in different cells were less than 0.5%. In terms of the MTT assay, the effect size differences were in the range of 0.1 to 0.5% (small to medium), which shows our study was in line with these other three studies. The synergistic actions of the p53 plasmid and RG7388 were studied in tumor-bearing female BALB/c nude mice after intravenous administration, which reduced the tumor growth of MCF7/WT xenografts due to the combined effects of both p53 plasmid and RG7388 in vivo [50]. Therefore we expect that our nanovehicle would show in vivo performance comparable to the above-cited studies since the in vitro effect sizes were comparable.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, poor water solubility, instability, and extremely low bioavailability are critical obstacles, which limit the clinical use of Cur. However several nano-sized Cur delivery systems have been employed to overcome these drawbacks, to boost the anti-cancer activity of this natural product. In the present study, we showed that the PAMAM-Cur/siRNA polyplex, not only increased the solubility and stability of Cur but also the combined effect of both Cur and Bcl-2 siRNA induced the most apoptosis in HeLa cancer cells. Despite various toxicological studies having been conducted on similar nano-constructs, extensive toxicological profiling and assessment of any harmful effects on healthy tissue, are indispensable before this approach could be used clinically. Therefore, future investigations should use an in vivo model for dose optimization for PAMAM-Cur and PAMAM-Cur/siRNA, and also assess the in vivo potential of these complexes as an effective and reliable strategy for treatment of cervical cancer.

Highlights.

A PAMAM dendrimer encapsulated curcumin and a polyplex with siRNA against BCL2

Characterization, drug release and photostability was investigated

Uptake by HeLa cells studied by fluorescence microscopy and FACS analysis

The nanoformulation showed higher cytotoxicity than PAMAM-Cur and free Cur

Apoptosis was studied by annexin-V and DAPI staining

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for supporting this project (grant No: 59561).

Funding

The study was supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences grant 59561

Michael R Hamblin was supported by US NIH Grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflicts of interest

Michael R Hamblin is on the following Scientific Advisory Boards

Transdermal Cap Inc, Cleveland, OH

BeWell Global Inc, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

Hologenix Inc. Santa Monica, CA

LumiThera Inc, Poulsbo, WA

Vielight, Toronto, Canada

Bright Photomedicine, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Quantum Dynamics LLC, Cambridge, MA

Global Photon Inc, Bee Cave, TX

Medical Coherence, Boston MA

NeuroThera, Newark DE

JOOVV Inc, Minneapolis-St. Paul MN

AIRx Medical, Pleasanton CA

FIR Industries, Inc. Ramsey, NJ

UVLRx Therapeutics, Oldsmar, FL

Ultralux UV Inc, Lansing MI

Illumiheal & Petthera, Shoreline, WA

MB Lasertherapy, Houston, TX

ARRC LED, San Clemente, CA

Varuna Biomedical Corp. Incline Village, NV

Niraxx Light Therapeutics, Inc, Boston, MA

Dr Hamblin has been a consultant for

Lexington Int, Boca Raton, FL

USHIO Corp, Japan

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany Philips Electronics Nederland B.V.

Johnson & Johnson Inc, Philadelphia, PA

Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Dr Hamblin is a stockholder in Global Photon Inc, Bee Cave, TX Mitonix, Newark, DE.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L, Cervical cancer, The Lancet, 393 (2019) 169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kamla P, Nida A, Nanocarriers for the Effective Treatment of Cervical Cancer: Research Advancements and Patent Analysis, Recent Patents on Drug Delivery & Formulation, 12 (2018) 93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Efferth T, Saeed MEM, Mirghani E, Alim A, Yassin Z, Saeed E, Khalid HE, Daak S, Integration of phytochemicals and phytotherapy into cancer precision medicine, Oncotarget, 8 (2017) 50284–50304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alibolandi M, Hoseini F, Mohammadi M, Ramezani P, Einafshar E, Taghdisi SM, Ramezani M, Abnous K, Curcumin-entrapped MUC-1 aptamer targeted dendrimer-gold hybrid nanostructure as a theranostic system for colon adenocarcinoma, International journal of pharmaceutics, 549 (2018) 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park BH, Lim JE, Jeon HG, Seo SI, Lee HM, Choi HY, Jeon SS, Jeong BC, Curcumin potentiates antitumor activity of cisplatin in bladder cancer cell lines via ROS-mediated activation of ERK½, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 63870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adiwidjaja J, McLachlan AJ, Boddy AV, Curcumin as a clinically-promising anti-cancer agent: pharmacokinetics and drug interactions, Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 13 (2017) 953–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kujundžić RN, Stepanić V, Milković L, Gašparović AČ, Tomljanović M, Trošelj KG, Curcumin and its Potential for Systemic Targeting of Inflamm-Aging and Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20 (2019) 1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banik U, Parasuraman S, Adhikary AK, Othman NH, Curcumin: the spicy modulator of breast carcinogenesis, Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 36 (2017) 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Song L, Jiang B, Su G, Li Y, Glutathione-responsive self-delivery nanoparticles assembled by curcumin dimer for enhanced intracellular drug delivery, International journal of pharmaceutics, 549 (2018) 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suo A, Qian J, Xu M, Xu W, Zhang Y, Yao Y, Folate-decorated PEGylated triblock copolymer as a pH/reduction dual-responsive nanovehicle for targeted intracellular co-delivery of doxorubicin and Bcl-2 siRNA, Materials Science and Engineering: C, 76 (2017) 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng T, Wei Y, Lee RJ, Zhao L, Liposomal curcumin and its application in cancer, Int J Nanomedicine, 12 (2017) 6027–6044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Xu X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Shi J, Sun Y, Huang Q, Encapsulation of curcumin within poly (amidoamine) dendrimers for delivery to cancer cells, Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, 24 (2013) 2137–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Lin Z, Zhao M, Xu T, Wang C, Xia H, Wang H, Zhu B, Multifunctional selenium nanoparticles as carriers of HSP70 siRNA to induce apoptosis of HepG2 cells, International Journal of Nanomedicine, 11 (2016) 3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z, Wang D, Cheng Y, Yang M, Wu L-P, Polyester based nanovehicles for siRNA delivery, Materials Science and Engineering: C, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Büyükköroğlu G, Şenel B, Başaran E, Yenilmez E, Yazan Y, Preparation and in vitro evaluation of vaginal formulations including siRNA and paclitaxel-loaded SLNs for cervical cancer, European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 109 (2016) 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W, Chen X, Xie C, Wang Y, Lin L, Zhu K, Shuai X, Co-delivery of doxorubicin and antiBCL-2 siRNA by pH-responsive polymeric vector to overcome drug resistance in in vitro and in vivo hepg2 hepatoma model, Biomacromolecules, 19 (2018) 2248–2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian J, Xu M, Suo A, Xu W, Liu T, Liu X, Yao Y, Wang H, Folate-decorated hydrophilic three-arm star-block terpolymer as a novel nanovehicle for targeted co-delivery of doxorubicin and Bcl-2 siRNA in breast cancer therapy, Acta biomaterialia, 15 (2015) 102–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young SW, Stenzel M, Yang JL, Nanoparticle-siRNA: A potential cancer therapy?, Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 98 (2016) 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abedi-Gaballu F, Dehghan G, Ghaffari M, Yekta R, Abbaspour-Ravasjani S, Baradaran B, Dolatabadi JEN, Hamblin MR, PAMAM dendrimers as efficient drug and gene delivery nanosystems for cancer therapy, Applied materials today, 12 (2018) 177–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu D, Yang J, Xing Z, Han H, Wang T, Zhang A, Yang Y, Li Q, Phenylboronic acidfunctionalized polyamidoamine-mediated Bcl-2 siRNA delivery for inhibiting the cell proliferation, Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 146 (2016) 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Liang H, Liu J, Wang Z, Poly (amidoamine)(PAMAM) dendrimer mediated delivery of drug and pDNA/siRNA for cancer therapy, International journal of pharmaceutics, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farhangi B, Alizadeh AM, Khodayari H, Khodayari S, Dehghan MJ, Khori V, Heidarzadeh A, Khaniki M, Sadeghiezadeh M, Najafi F, Protective effects of dendrosomal curcumin on an animal metastatic breast tumor, European journal of pharmacology, 758 (2015) 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babaei E, Sadeghizadeh M, Hassan ZM, Feizi MAH, Najafi F, Hashemi SM, Dendrosomal curcumin significantly suppresses cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo, International immunopharmacology, 12 (2012) 226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Razi MA, Wakabayashi R, Tahara Y, Goto M, Kamiya N, Genipin-stabilized caseinate-chitosan nanoparticles for enhanced stability and anti-cancer activity of curcumin, Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 164 (2018) 308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nambiar S, Osei E, Fleck A, Darko J, Mutsaers AJ, Wettig S, Synthesis of curcuminfunctionalized gold nanoparticles and cytotoxicity studies in human prostate cancer cell line, Applied Nanoscience, (2018) 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medel S, Syrova Z, Kovacik L, Hrdy J, Hornacek M, Jager E, Hruby M, Lund R, Cmarko D, Stepanek P, Curcumin-bortezomib loaded polymeric nanoparticles for synergistic cancer therapy, European Polymer Journal, 93 (2017) 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C, Ge X, Wang L, Construction and comparison of different nanocarriers for co-delivery of cisplatin and curcumin: a synergistic combination nanotherapy for cervical cancer, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 86 (2017) 628–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumari P, Rompicharla SVK, Muddineti OS, Ghosh B, Biswas S, Transferrin-anchored poly (lactide) based micelles to improve anticancer activity of curcumin in hepatic and cervical cancer cell monolayers and 3D spheroids, International journal of biological macromolecules, 116 (2018) 1196–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kesharwani P, Xie L, Banerjee S, Mao G, Padhye S, Sarkar FH, Iyer AK, Hyaluronic acidconjugated polyamidoamine dendrimers for targeted delivery of 3, 4-difluorobenzylidene curcumin to CD44 overexpressing pancreatic cancer cells, Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 136 (2015) 413423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luong D, Kesharwani P, Alsaab HO, Sau S, Padhye S, Sarkar FH, Iyer AK, Folic acid conjugated polymeric micelles loaded with a curcumin difluorinated analog for targeting cervical and ovarian cancers, Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 157 (2017) 490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Azami A, Mohammadi A, Hamishehkar H, Panahi-Azar V, Rahbar Saadat Y, Saei AA, Formulation, characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation of ketotifen-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers, Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 46 (2018) 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash H, Sohrabi Y, Mohammadi A, Shanehbandi D, Dehghan P, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Safety assessment of sodium acetate, sodium diacetate and potassium sorbate food additives, Food Chemistry, 257 (2018) 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiwari PM, Eroglu E, Bawage SS, Vig K, Miller ME, Pillai S, Dennis VA, Singh SR, Enhanced intracellular translocation and biodistribution of gold nanoparticles functionalized with a cellpenetrating peptide (VG-21) from vesicular stomatitis virus, Biomaterials, 35 (2014) 9484–9494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang M, Han HD, Ahn HJ, A RNA nanotechnology platform for a simultaneous two-in-one siRNA delivery and its application in synergistic RNAi therapy, Scientific reports, 6 (2016) 32363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu S, Gong L.-s., Li N.-f., Pan Y.-f., Zhang L, Galangin (GG) combined with cisplatin (DDP) to suppress human lung cancer by inhibition of STAT3-regulated NF-Œ∫B and Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathways, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 97 (2018) 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakhtiary Z, Barar J, Aghanejad A, Saei AA, Nemati E, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Omidi Y, Microparticles containing erlotinib-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, Drug development and industrial pharmacy, 43 (2017) 1244–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao J, Zhang H, Wang Y, Yang J, Jiang F, Investigation on the interaction behavior between curcumin and PAMAM dendrimer by spectral and docking studies, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 108 (2013) 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A, Khorasani S, Mozafari M, Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems, Pharmaceutics, 10 (2018) 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cabeza L, Ortiz R, Arias JL, Prados J, Martínez MAR, Entrena JM, Luque R, Melguizo C, Enhanced antitumor activity of doxorubicin in breast cancer through the use of poly (butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles, International journal of nanomedicine, 10 (2015) 1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu S, Gong L.-s., Li N.-f., Pan Y.-f., Zhang L, Galangin (GG) combined with cisplatin (DDP) to suppress human lung cancer by inhibition of STAT3-regulated NF-κB and Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathways, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 97 (2018) 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, Medeiros LJ, Young KH, Apoptosis signaling and BCL-2 pathways provide opportunities for novel targeted therapeutic strategies in hematologic malignances, Blood reviews, 32 (2018) 8–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabeza L, Ortiz R.l., Arias JL, Prados J, Martínez MAR, Entrena JM, Luque R, Melguizo C.n., Enhanced antitumor activity of doxorubicin in breast cancer through the use of poly (butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles, International journal of nanomedicine, 10 (2015) 1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reuter S, Eifes S, Dicato M, Aggarwal BB, Diederich M, Modulation of anti-apoptotic and survival pathways by curcumin as a strategy to induce apoptosis in cancer cells, Biochemical pharmacology, 76 (2008) 1340–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han S.-z., Liu H.-x., Yang L.-q., Xu Y, Piperine (PP) enhanced mitomycin-C (MMC) therapy of human cervical cancer through suppressing Bcl-2 signaling pathway via inactivating STAT3/NF-κB, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 96 (2017) 1403–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee SJ, Yook S, Yhee JY, Yoon HY, Kim M-G, Ku SH, Kim SH, Park JH, Jeong JH, Kwon IC, Co-delivery of VEGF and Bcl-2 dual-targeted siRNA polymer using a single nanoparticle for synergistic anti-cancer effects in vivo, Journal of Controlled Release, 220 (2015) 631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghaffari M, Dehghan G, Abedi-Gaballu F, Kashanian S, Baradaran B, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Losic D, Surface functionalized dendrimers as controlled-release delivery nanosystems for tumor targeting, European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 122 (2018) 311–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Souho T, Lamboni L, Xiao L, Yang G, Cancer hallmarks and malignancy features: Gateway for improved targeted drug delivery, Biotechnology advances, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J-M, Zhang W, Su H, Wang Y-Y, Tan C-P, Ji L-N, Mao Z-W, Reversal of multidrug resistance in MCF-7/Adr cells by codelivery of doxorubicin and BCL2 siRNA using a folic acidconjugated polyethylenimine hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin nanocarrier, International Journal of Nanomedicine, 10 (2015) 3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yadav P, Bandyopadhyay A, Chakraborty A, Sarkar K, Enhancement of anticancer activity and drug delivery of chitosan-curcumin nanoparticle via molecular docking and simulation analysis, Carbohydrate polymers, 182 (2018) 188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen K, Xin X, Qiu L, Li W, Guan G, Li G, Qiao M, Zhao X, Hu H, Chen D, Co-delivery of p53 and MDM2 inhibitor RG7388 using a hydroxyl terminal PAMAM dendrimer derivative for synergistic cancer therapy, Acta Biomaterialia, 100 (2019) 118–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]