Abstract

Autophagy-related gene-6 (Beclin-1 in mammals) plays a pivotal role in autophagy and is involved in autophagosome formation and autolysosome maturation. In this study, we identified and characterized the autophagy-related gene-6 from Tenebrio molitor (TmAtg6) and analyzed its functional role in the survival of the insect against infection. The expression of TmAtg6 was studied using qRT-PCR for the assessment of the transcript levels at various developmental stages in the different tissues. The results showed that TmAtg6 was highly expressed at the 6-day-old pupal stage. Tissue-specific expression studies revealed that TmAtg6 was highly expressed in the hemocytes of late larvae. The induction patterns of TmAtg6 in different tissues of T. molitor larvae were analyzed by injecting Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, or Candida albicans. The intracellular Gram-positive bacteria, L. monocytogenes, solely induced the expression of TmAtg6 in hemocytes at 9 h-post-injection, whilst in the fat body and gut, bimodal expression times were observed. RNAi-mediated knockdown of the TmAtg6 transcripts, followed by a challenge with microbes, showed a significant reduction in larval survival rate against L. monocytogenes. Taken together, our results suggest that TmAtg6 plays an essential role in anti-microbial defense against intracellular bacteria.

Keywords: TmAtg6, induction pattern, autophagy, intracellular bacteria, RNAi

1. Introduction

Macroautophagy (autophagy) collectively refers to a group of intracellular degradation pathways that mediate the breakdown of intracellular material in lysosomes [1,2]. It is an evolutionarily conserved, catabolic process associated with multiple biological and physiological processes. Besides, it performs protective and defensive functions with respect to innate immunity, inflammation, and resistance against microbial infection [3,4].

The process of autophagy extends from autophagosome formation to the degradation of non-self, damaged, or surplus cell components by lysosomal hydrolases via a series of steps [5,6]. In selective autophagy, the specific cargos are first tagged by ubiquitination and recognized by the autophagy adaptor molecules for subsequent targeting to autophagosomes for degradation [7]. The selective autophagy mainly targets misfolded proteins, damaged organelles, and intracellular pathogens like Mycobacterium spp., Salmonella spp., and Listeria spp. [8]. Based on the cargo being delivered for degradation, xenophagy is the cargo that contains intracellular pathogens [8]. Therefore, in xenophagy, pathogen-containing phagosomes are exclusively targeted for autophagic degradation [9]. In either no-selective or selective autophagy, various autophagy-related genes are involved in different stages of autophagy (initiation, phagophore formation, elongation, and completion) [10].

In yeast, where the majority of the molecular mechanisms of autophagy have been studied, the Atg1 kinase complex with Atg13 and Atg17 induces membrane isolation and initiates autophagy [11,12]. The phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) 3-kinase complex (complex I: Vps15-Vps34-Vps30/ Atg6-Atg14; and complex-II: Vps15-Vps34-Vps30/Atg6-Atg14-Vps38) [13,14] and Atg9 complex [15] affect phosphoinositides to recruit proteins for phagophore and autophagosome formation. Finally, the ubiquitin-like protein conjugation complexes (Atg8, Atg12, Atg4, Atg7, and Atg3, among other proteins) elongate and complete the autophagy process [16]. The roles of TmAtg3, TmAtg5, and TmAtg8 in mediating the autophagy-based clearance of Listeria in T. molitor have been investigated previously [17,18].

Atg6 (Beclin-1 in mammals) is highly conserved between yeast and mammals. It plays a pivotal role in autophagy and is involved in autophagosome formation and autolysosome maturation by forming a complex with Vps34, Vps15, UVRAG, and Vps38 [19].

Atg6 is relatively unique since it is not only autophagy-specific, but also has different functions; for example, the Atg6/Vps30 complex is required for autophagy, sorting vacuolar contents [20], and pollen germination [21], and acts as a tumor suppressor gene [22,23]. Therefore, biologically, Atg6 is required for life span extension in both animals and plants in supplying the cells with energy under adverse conditions, maintaining critical levels of metabolism, and clearing microbial infections. However, the molecular function of Atg6 in T. molitor has not yet been studied. Thus, we sought to identify the function of Atg6 in T. molitor with respect to the molecular mechanism of autophagy during microbial infection in beetles. Therefore, in this study, we characterized the role of TmAtg6 in insect survivability against bacterial challenge using RNAi gene silencing. We demonstrated that TmAtg6 has a specific molecular function in the immune response against the intracellular bacteria, L. monocytogenes.

2. Results

2.1. Sequence Identification and In Silico Analysis of TmAtg6

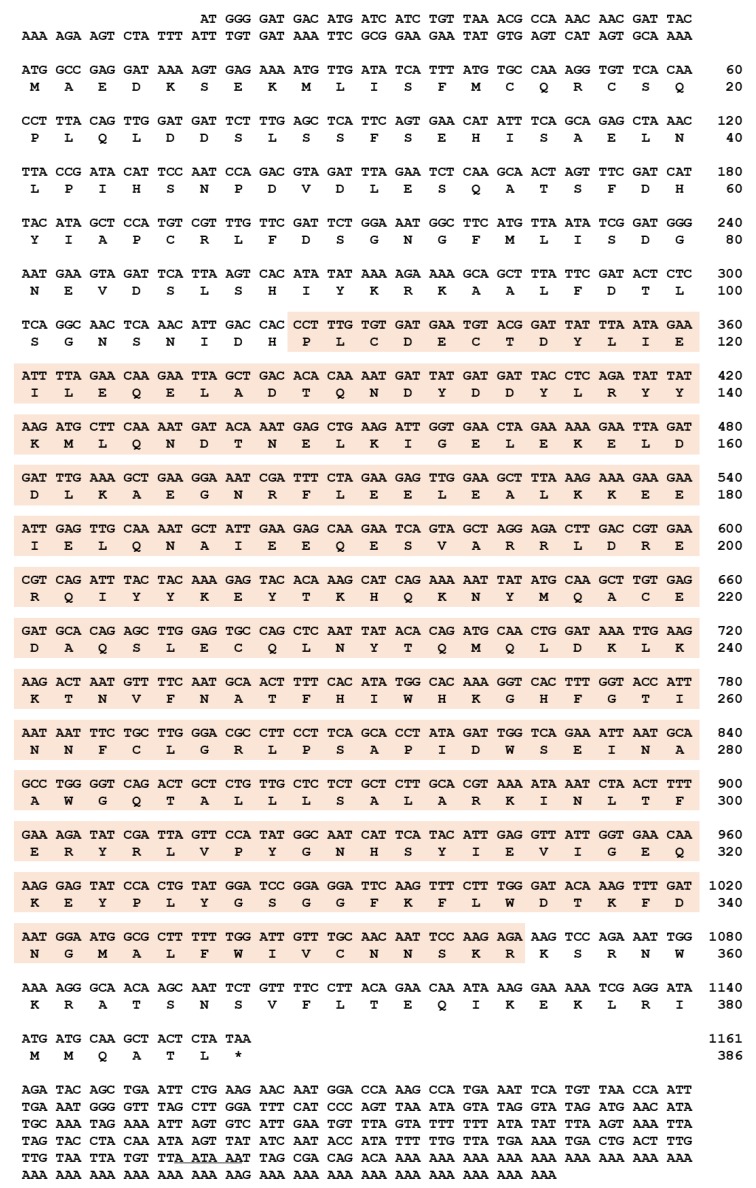

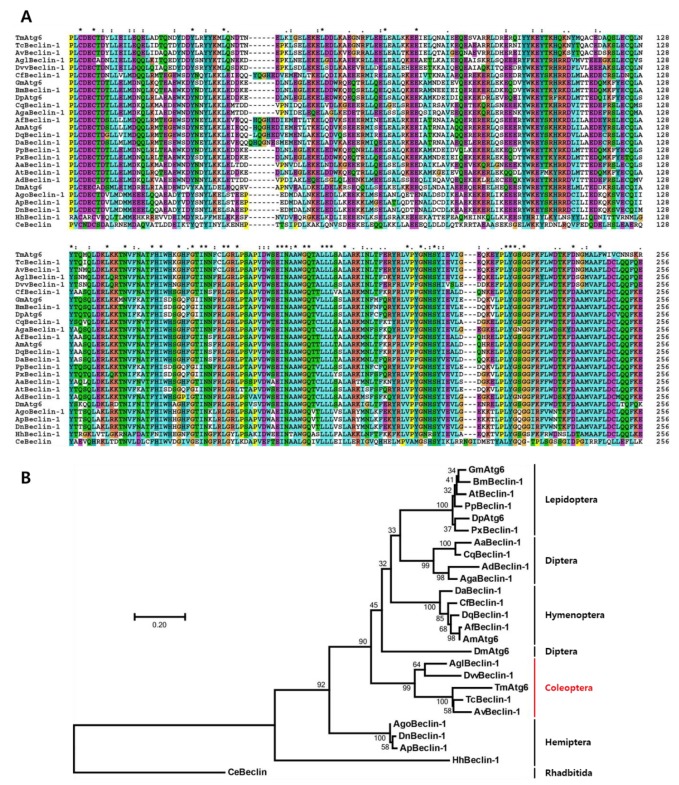

Full-length cDNA sequence of TmAtg6 was obtained from the T. molitor RNAseq database and 5′- / 3′-RACE PCR. TmAtg6 contains an open reading frame (ORF) of 1161 bp that encodes a protein of 386 amino acid residues (Figure 1). The 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTR) of TmAtg6 were 105 and 348 bp in length, respectively. The poly (A) signal (AATAAA) was found 9 bp upstream of the poly (A) tail. The multiple alignments of TmAtg6 amino acid sequence with its orthologs indicates a high degree of conservation in the Atg6 amino acid sequence within insects (Figure 2A). The phylogenetic analysis revealed Coleopteran insects (Asbolus verrucosus beclin-1-like protein and Tribolium castaneum Beclin-1-like protein) grouped together (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the percentage of identity showed that TmAtg6 is closest to Tribolium castaneum (TcBeclin-1) since they share the highest sequence identity (89%) (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of TmAtg6. The full-length open reading frame (ORF) sequence of TmAtg6 gene was identified. TmAtg6 has 1161 bp of ORF encoding 386 amino acid (aa) residues. Domain analysis indicates that TmAtg6 contains one Atg6 domain. The polyadenylation signal sequence (AATAA) is underlined in the 3′-UTR region and the TmAtg6 domain is shaded in orange.

Figure 2.

Multiple alignments and molecular phylogenetic analysis of insect beclin-1 homologs protein. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of TmAtg6 along with its homologs. The highly conserved beclin-1 domain was aligned by using Clustal X2 software. The symbols indicate conservation scores between groups according to the Gonnet PAM 250 matrix (‘*’ > ‘:’ > ‘.’) and ‘−’ indicates internal or terminal gaps. (B) Phylogenetic analyses of TmAtg6 homologs were performed based on the multiple alignments using the Clustal X2 and the phylogenic tree was constructed by MEGA7 programs using the maximum likelihood and bootstrapped of 1000 replications. The red color text with vertical line used to indicate the coleopteran order grouped together. Phylogenetic analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans beclin-1 sequence was used as the outgroup. The following protein sequences were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. TmAtg6 (Tenebrio molitor Autophagy-related 6), TcBeclin-1 (Tribolium castaneum Beclin-1-like protein; EFA06871.2), AvBeclin-1 (Asbolus verrucosus beclin-1-like protein; RZC37309.1), AglBeclin-1 (Anoplophora glabripennis beclin-1-like protein; XP_018570978.1), DvvBeclin-1 (Diabrotica virgifera beclin-1-like protein; XP_028144478.1), AgoBeclin-1 (Aphis gossypii beclin-1-like protein; XP_027849435.1), ApBeclin-1 (Acyrthosiphon pisum beclin-1-like protein; XP_016661093.1), HhBeclin-1 (Halyomorpha halys beclin-1-like protein; XP_014275231.1), DnBeclin-1 (Diuraphis noxia PREDICTED: beclin-1-like protein; XP_015372132.1), AaBeclin-1 (Aedes aegypti AAEL010427-PA; EAT37604.1)’ AdBeclin-1 (Anopheles darling beclin-1; ETN63629.1), AgaBeclin-1 (Anopheles gambiae str. PEST AGAP003858-PA; EAA06006.4), CqBeclin-1 (Culex quinquefasciatus beclin-1 EDS35627.1), DmAtg6 (Drosophila melanogaster Autophagy-related 6; AAF56227.1), DpAtg6 (Danaus plexippus autophagy related protein Atg6; EHJ78273.1), GmAtg6 (Galleria mellonella autophagy related protein Atg6; AFP66875.1), PpBeclin-1 (Papilio polytes beclin-1-like protein; XP_013145468.1), PxBeclin-1 (Plutella xylostella beclin-1-like protein; XP_011559638.1), BmBeclin-1 (Bombyx mori autophagy related protein Atg6; ACJ46062.1), AtBeclin-1 (Amyelois transitella beclin-1-like protein XP_013199196.1), AfBeclin-1 (Apis florea beclin-1-like protein isoform X1; XP_003696795.1), AmAtg6 (Apis mellifera autophagy specific gene 6 isoform X2; XP_392365.1), DaBeclin-1 (Diachasma alloeum beclin-1-like protein isoform X1; XP_015116372.1), CfBeclin-1 (Camponotus floridanus beclin-1-like protein isoform X1; XP_011257589.1), DqBeclin-1 (Dinoponera quadriceps beclin-1-like protein isoform X2; XP_014479707.1), CeBeclin (Caenorhabditis elegans Beclin (human autophagy) homolog; CCD62215.1).

2.2. Developmental and Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of TmAtg6

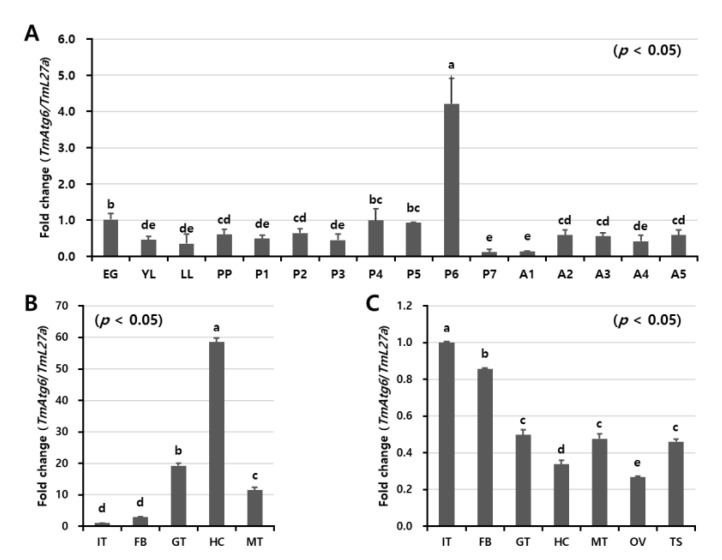

The expression levels of TmAtg6 transcripts at different developmental stages and tissues were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Figure 3A). TmAtg6 transcripts were detected through all developmental stages and in all examined tissues. The highest expression level was observed in pupal stages, specifically in six-day-old pupae. Comparatively lower TmAtg6 transcript levels were observed in young and late instar larvae, 7-day-old pupae, and 1-day-old adults.

Figure 3.

Developmental and tissue-specific expression patterns of TmAtg6 gene. (A) The developmental stages of mealworm, egg (EG), young larvae (YL), late larvae (LL), pre-pupa (PP), 1–7-days old pupae (P1–P7), and 1–5-days old adult (A1–A5), were examined to study the expression level of TmAtg6. For each stage, 20 individuals were used to extract RNA with the subsequent synthesis of cDNA. The results indicate that TmAtg6 expression was gradually increased from young larvae to 2-days old pupae with highest expression at the 6-days old pupal stage. In adult stages, there was no considerable expression difference. Tissue-specific expression patterns of TmAtg6 genes in late larvae (B) and in 5-day-old adults (C). Hemocytes, gut, fat body, Malpighian tubules, and integument (for late instar larvae and adults), and testes and ovaries (for adults) were dissected and collected from a total of 20 late larvae and 5-day-old adults. The results indicate that TmAtg6 was highly expressed in hemocytes, while low expression was observed in the integument and fat body in late larvae. In adults, the expression levels of TmAtg6 were high in fat body and integument. IT; integument, GT; gut, FB; fat body, HC; hemocytes, MT; Malpighian tubules, OV; ovary, and TS; testis. Tenebrio ribosomal protein 27a (TmL27a) was used as internal control.

In the tissues, the highest TmAtg6 expression levels were observed in the hemocytes of late larvae and the integument and fat body of adults (Figure 3B,C). Conversely, TmAtg6 expression levels were low in the integument of late larvae and the hemocytes of adults.

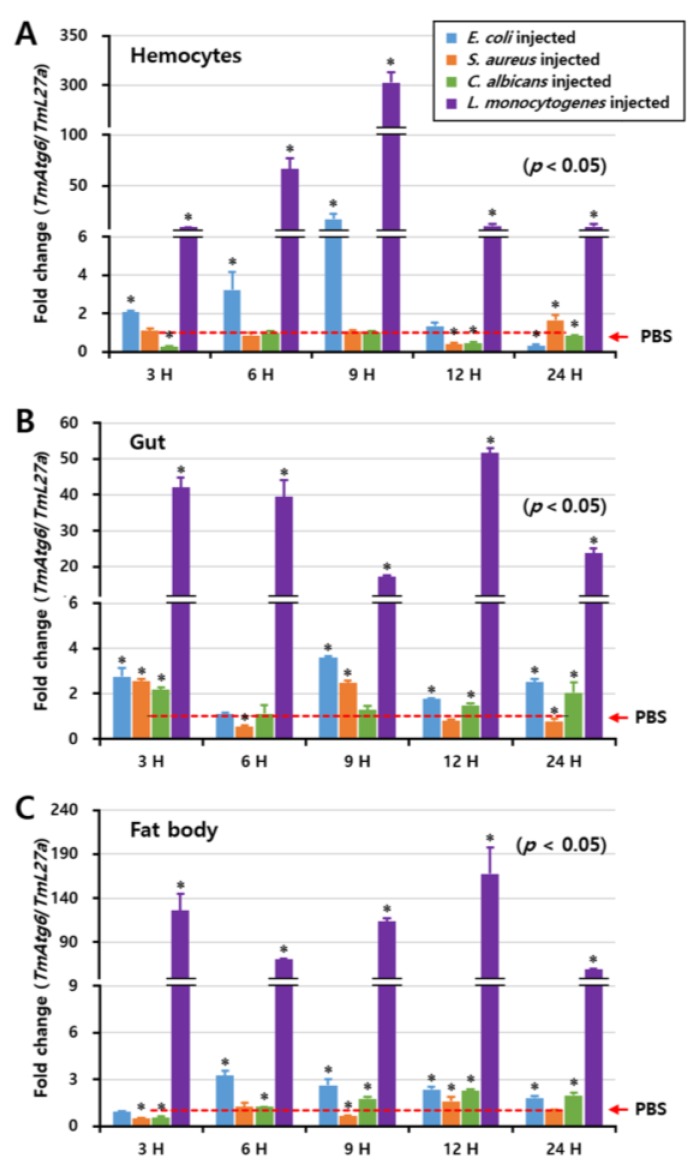

2.3. Temporal Induction Pattern of TmAtg6

To investigate the inducibility of the TmAtg6 gene, E. coli, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, or C. albicans were injected into T. molitor larvae and the three immune tissues such as hemocytes, fat body, and gut were time-dependently (at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h post-injection) collected for the analysis of the induction pattern by qRT-PCR. Remarkably, TmAtg6 mRNA was highly induced by L. monocytogenes in all tissues (Figure 4), whereas E. coli, S. aureus, and C. albicans slightly induce TmAtg6 mRNA. In hemocytes, the induction of TmAtg6 by L. monocytogenes showed the highest expression at 9 h post-injection. In the gut, TmAtg6 expression was represented in two patterns, being highly expressed at 3 h post-injection, slightly expressed at 6 and 9 h post-injection, and increased again at 12 h post-injection. In the fat body, the highest expression of TmAtg6 was detected at 3 and 12 h post-injection of L. monocytogenes.

Figure 4.

Induction patterns of TmAtg6 in different tissues against E. coli, S. aureus, C. albicans, and L. monocytogenes, including hemocytes (A), gut (B), and fat body (C). The induction pattern analysis of TmAtg6 gene in different tissues of T. molitor young larvae was performed by injection of E. coli (106 cells/μL), S. aureus (106 cells/μL), C. albicans (5 × 104 cells/μL), or L. monocytogenes (106 cells/μL). Samples were collected at different time points such as 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h post-injection of microorganisms. Twenty young larvae of mealworm were used at each time point. In hemocytes, TmAtg6 gene was highly induced at 9 h post-injection of L. monocytogenes. In the gut, the injection of L. monocytogenes highly induced the expression of TmAtg6 at 3 h post-injection, gradually decreased during 6 and 9 h, and then highly induced levels of TmAtg6 12 h post-injection. In the fat body, injection of L. monocytogenes highly induced TmAtg6 at 12 h post-infection.

2.4. Effect of TmAtg6 RNAi on T. molitor Survivability

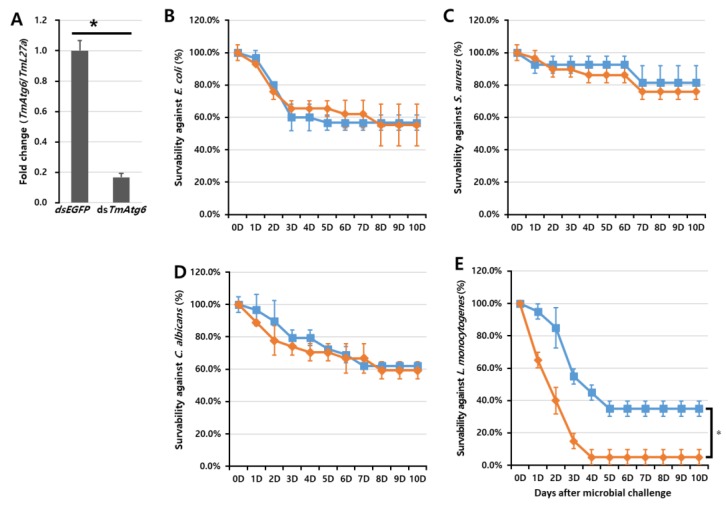

To characterize the function of TmAtg6 against microorganisms, we silenced its transcript levels using RNAi and challenged T. molitor larvae with prepared microorganisms. The percentage of TmAtg6 downregulation was confirmed (84% knockdown) by qRT-PCR prior to microbial challenge. The survivability of the TmAtg6-silenced T. molitor larvae against microbial injection was monitored for 10 days. The injection of dsTmAtg6 and/or dsEGFP did not affect the survival of T. molitor larvae when injected with the control PBS. Compared to the dsEGFP-injected larval group, no significant difference was detected in the dsTmAtg6-injected group on larval survivability against any of the tested microorganisms except L. monocytogenes (Figure 5). Surprisingly, TmAtg6-silenced larvae showed higher susceptibility against L. monocytogenes compared to the dsEGFP group.

Figure 5.

RNA interference (RNAi)-based functional study of TmAtg6 in Tenebrio molitor larvae. Larval survival curves following infection with microorganisms. TmAtg6 knockdown (A), E. coli (B), S. aureus (C), C. albicans (D), L. monocytogenes (E). * significant at p < 0.05. Results represent the average of three independent replicates with standard error. TmAtg6 gene silencing significantly affected the survivability of T. molitor larvae against L. monocytogenes infection. In contrast, the TmAtg6 gene silencing did not show significant differences in survivability against E. coli, S. aureus, and C. albicans.

3. Discussion

Autophagy 6 (Beclin 1 in mammalian), as a key regulator of autophagy [24], has many functions in intracellular processes such as signaling pathways, vacuolar protein sorting [25], endocytic trafficking, apoptosis [26], and degradation of sequestered cytoplasmic contents, including damaged organelles and pathogens [27,28]. Additionally, crosstalk between autophagy and antiviral immunity has been reported, suggesting the dual effect of autophagy as promoting the clearance of viral components and activating the immune system to produce antiviral cytokines [29]. Therefore, Atg6 is an essential gene required for both development and host immunity. Specifically, the induction of autophagy (autophagosome formation) in mammals mainly depends on the Class III PI3K complex, comprising hVps34, Beclin-1, p150, and Atg14-like protein or ultraviolet irradiation resistance-associated gene (UVRAG) [30]. Similarly, in yeast, complex I (Vps15-Vps34-Vps30/Atg6-Atg14) and complex II (Vps15-Vps34-Vps30/Atg6-Atg14-Vps38) are required in autophagy and vascular protein sorting, respectively [13,30]. Thus, the current study was conducted to characterize the immune functions of TmAtg6 in T. molitor.

During the development and metamorphosis of holometabolous insects, cell death occurs at each stage, and the mechanisms of cell debris removal are essential in many aspects [31]. Therefore, the roles of autophagy in development and the clearance of invading pathogens have been extensively investigated [32,33,34,35]. For instance, autophagy occurs during the remodeling and degeneration of various larval tissues [36,37], as well as during changes in larval instars and larva–pupa transition [36,38]. Our observations regarding TmAgt6 expression in different developmental stages and tissues also suggest its importance in the growth and development of T. molitor. In particular, the highest expression of TmAtg6 in 6-day-old pupae may suggest that autophagy occurs during metamorphosis from pupae to adults. Likewise, the function of autophagy during metamorphic transition has been well characterized in Heliothis virescens [39] and Alabama argillacea [40]. Additionally, in the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the expression levels of several Atg genes including BmAtg1, -2, -6, -11, -12, -13, and -18 were high during molting and pupation stages when levels of the steroid hormone (20-hydroxyecdysone; 20E) were high [41]. Similarly, in T. molitor, the TmAtg8, -5, -3, and -13 transcripts were expressed in all tissues, suggesting their importance in the cell remodeling process and development [17,18,42]. Moreover, the expression of TmAtg6 in the hemocytes of T. molitor larvae suggests the function of TmAtg6 in insect development. Hemocytes have been reported as vital components in the synthesis and transport of nutrients and hormones for proper growth and development and in wound healing by clearance of dead cells through phagocytosis and autophagy [43,44].

Studies show that autophagy plays an important role in not only developmental functions, but also in immunological functions such as bacterial, viral, and parasitoid clearance. In mosquitoes, the autophagy pathway is relevant to the replication and transmission of arboviruses [45,46,47]. However, in other insect species, it has been reported that autophagy is induced and is crucial for the innate cellular immune response against several intracellular bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens [48,49,50]. Additionally, the involvement of granulocyte-associated autophagy in hemocytes was immunologically and morphologically studied, showing a high accumulation of autophagic vacuoles in activated hemocytes granulocytes [51]. For example, in Drosophila, studies on the importance of antiviral autophagy against Rift Valley fever virus and Vesicular stomatitis virus revealed that viral replication was increased in the absence of autophagy genes [52,53]. Moreover, the pattern-recognition receptor, Peptidoglycan-recognition protein LE (PGRP-LE), was identified as a recognition protein of the diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan derived from Gram-negative bacteria to induce autophagy, consequently preventing the growth of L. monocytogenes and promoting host survivability [54]. Our current induction studies also revealed that TmAtg6 is highly expressed in all tissues exclusively infected with L. monocytogenes. TmAtg6 is comparatively highly expressed in hemocytes. Supporting this result, Bénédicte and his colleagues reported that autophagy targets L. monocytogenes during primary infection to limit the onset of early bacterial growth [49]. Interestingly, TmAtg6 expression was particularly downregulated by E. coli, S. aureus, and C. albicans at different time points. Supporting our current finding, in the mammalian model, some microorganisms downregulate ATG genes to avoid antimicrobial autophagy [55]. This downregulation is achieved through the modification of phagosomes by blocking their maturation via fusion with autophagosomes [56]. Additionally, in insects, autophagy-associated genes are downregulated by Wolbachia through the suppression of the autophagic signal to prevent their elimination [57].

Moreover, we studied the function of TmAtg6 in the defense response against microbial infection by silencing TmAtg6 protein expression. The gene-silenced larval group showed significant susceptibility to L. monocytogenes infection, indicating that TmAtg6 is directly involved in counteracting intracellular pathogen infection in the mealworms. The previous studies also reported that the other autophagy-related genes are involved in the defense response to L. monocytogenes (TmAtg3, TmAtg5, Tmatg8) [17,18], E. coli, and S. aureaus (TmAtg13) [42]. Collectively, TmAtg6 plays an important role in the autophagy-dependent defense response against the intracellular pathogen L. monocytogenes in T. molitor.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Insect Rearing and Maintenance

The coleopteran insect, Tenebrio molitor (mealworm), was maintained at 27 ± 1 °C and 60% ± 5% relative humidity in the dark with an artificial diet prepared from 170 g of whole-wheat flour, 20 g of fried bean powder, 10 g of soy protein, 100 g of wheat bran, 200 mL of sterile water, 0.5 g of chloramphenicol, 0.5 g of sorbic acid, and 0.5 mL of propionic acid. For the experiments, the 10 to 12 instar larvae were used. To ensure uniformity in size, the larvae were separated according to their physical size using a set of laboratory test sieves (Pascall Eng. Co. Ltd, Crawley, Sussex, England).

4.2. Preparation of Microorganisms

The following microorganisms were used in this study: Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli K12), Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus RN4220 and Listeria monocytogenes), and fungi (Candida albicans). The microorganisms were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB; E. coli and S. aureus), Sabouraud dextrose (C. albicans), and brain heart infusion (BHI; L. monocytogenes) broths at 37 °C overnight and subcultured at 37 °C for 3 h. Then the microorganisms were harvested and washed 2 times by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 min in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.0). They were then suspended in PBS and the concentrations were measured at OD600. Finally, 106 cells/μL of E. coli, S. aureus, and L. monocytogenes and 5 × 104 cells/μL of C. albicans were injected separately.

4.3. Identification and Cloning of Full-Length cDNA Sequence of TmAtg6

The T. molitor Atg6 gene was identified by local-blastn analysis (National Center for Biotechnology Information) with the amino acid sequence of the T. castaneum Atg6 gene (EFA06871.2) as the query search. The partial cDNA sequence of TmAtg6 was obtained from T. molitor RNAseq database and the full-length cDNA sequence of TmAtg6 (MN259540) was identified by 5′- and 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA end (RACE) PCR using a SMARTer RACE cDNA amplification kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed using the AccuPower® PyroHotStart Taq PCR PreMix (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea) with TmAtg6 specific primers (RACE primers included TmAtg6 -cloning_Fw and TmAtg6 -cloning_Rv; Table 1). PCR was carried out under the following conditions: Pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min using a MyGenie96 Thermal Block (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea). PCR products were purified using an AccuPrep® PCR Purification Kit (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea), immediately ligated into T-Blunt vectors (Solgent, Deajeon, Korea), and transformed into DH5α competent cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmid DNA was extracted from fully grown competent cells using an AccuPrep® Nano-Plus Plasmid Extraction Kit (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea), sequenced, and analyzed. Finally, the full-length cDNA sequence of TmAtg6 was obtained.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used in this study.

| Name | Primers sequence |

|---|---|

| TmAtg6_qRTPCR_Fw TmAtg6-qRTPCR-Rv |

5′-AGCTCCaTGTCGTTTGTTCG-3′ 5′-GGTGGTCAATGTTTGAGTTGCC-3′ |

| TmAtg6-T7_Fw TmAtg6-T7-Rv |

5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGT AGCTCCATGTCGTTTGTTCG-3′ 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGT GTCAATGTTTGAGTTGCC-3′ |

| TmBeclin1 5′RACE GSP1 TmBeclin1 5′RACE GSP2 |

5′-TGTGAACACCTTTGGCACAT-3′ 5′-CACACAAAGGGTGGTCAATG-3′ |

| TmBeclin1 3′RACE GSP1 TmBeclin1 3′RACE GSP2 |

5′-GAAATTGGAAAAGGGCAACA-3′ 5′-TGCTCTGTTGCTCTCTGCTC-3′ |

| TmL27a_qPCR_Fw TmL27a_qPCR_Rv |

5′-TCATCCTGAAGGCAAAGCTCCAGT-3′ 5′-AGGTTGGTTAGGCAGGCACCTTTA-3′ |

| dsEGFP_Fw dsEGFP_Rv |

5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGT CGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTC-3′ 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGT TGCTCAGGTAGTGTTGTCG-3′ |

※ Underlines indicate T7 promoter sequences.

4.4. Domain Analysis and Phylogenetic Analysis

Specific domains were analyzed using the InterProScan 5 and blastp programs [58,59]. Multiple alignments were performed with representative Atg6 protein sequences of other insects obtained from Genbank using Clustal X2 software [60]. Phylogenetic and percentage identity analyses were conducted using Clustal X2 and MEGA 7 programs [61]. The amino acid sequences of CeBeclin of Rhabditida were used as outgroups.

4.5. Expression Analysis of TmAtg6

Whole-body samples were collected from T. molitor (n = 20) at various developmental stages, including the eggs (EG), young instar larvae (YL; 10th–12th instar larvae), late instar larvae (LL; 19th–20th instar larvae), prepupae (PP), 1 to 7-day-old pupae (P1–P7), and 1 to 5-day-old adults (A1–A5). To investigate tissue-specific TmAtg6 expression patterns, samples were collected from various tissues (n = 20), including the gut, hemocytes, integument, Malpighian tubules, and fat body of late instar larvae and 5-day-old adults, and the ovaries and testes of the adults. In addition, tissue-specific induction pattern analysis of the TmAtg6 gene was performed by injecting E. coli, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, or C. albicans. Three well-known immune tissues such as hemocytes, fat body, and gut were dissected and collected at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h post-injection. Samples were collected in 500 μL of guanidine thiocyanate RNA lysis buffer (2 mL of 0.5 M EDTA, 1 mL of 1 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) Buffer, 17.72 g of guanidine thiocyanate, 0.58 g of sodium chloride, 0.7 mg of phenol red, 25 μL of Tween-80, 250 μL of acetic acid glacial, and 500 μL of isoamyl alcohol) and homogenized using a homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) at 7500 rpm for 20 s.

Total RNAs were extracted from the collected samples using the modified LogSpin RNA isolation method [62]. Briefly, the homogenized samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm and 4 °C. The supernatant (300 μL) was transferred into a new 1.5 mL tube, mixed with 1 volume of pure ethanol, transferred into a silica spin column (Bioneer, Missouri City, Texas, USA, KA-0133-1), and centrifuged for 30 s at 13,000 rpm and 4 °C. The silica spin column was treated with DNase (Promega, Deajeon, Korea, M6101) at 25 °C for 15 min and washed with 3 M sodium acetate buffer and 80% ethanol. After drying by centrifugation for 2 min at 13,000 rpm and 4 °C, total RNAs were eluted with 30 μL of distilled water (Sigma, USA, W4502-1L). cDNAs were immediately synthesized with 2 μg of total RNAs using an AccuPower® RT PreMix (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea) and Oligo (dT) 12–18 primers on a MyGenie96 Thermal Block (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) reactions were performed using an Exicycler™ 96 Real-Time Quantitative Thermal Block (Bioneer Company, Daejeon, Korea) with a gene-specific primers and AccuPower® 2X GreenStar qPCR Master Mix (Bioneer, Deajeon, Korea) under the following conditions: Initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 45 cycles of denaturation at 9 °C for 15 s, and annealing at 60 °C for 30 s. The 2−ΔΔCt method [63] was employed to analyze TmAtg6 expression levels. T. molitor ribosomal protein L27a (TmL27a) was used as an internal control to normalize differences in template concentration between samples.

4.6. TmAtg6 Gene Silencing

cDNA synthesized from T. molitor hemocytes was amplified by semi-quantitative PCR using TmAtg6 gene-specific primers (product size; 500 bp, listed in Table 1) conjugated with a T7 promoter sequence designed using SnapDragon software (http://www.flyrnai.org/cgi-bin/RNAi_find_primers.pl). The PCR reaction was carried out under the following conditions: Initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified using the AccuPrep PCR Purification Kit (Bioneer Company, Daejeon, South Korea), and dsRNA was synthesized using an Ampliscribe™ T7-Flash™ Transcription Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After synthesis, dsRNA was purified using 5 M ammonium acetate and precipitated by 80% ethanol. Subsequently, it was quantified using an Epoch spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT, USA). As a control, we synthesized dsRNA for enhanced green fluorescent protein (dsTmEGFP) and stored at −20 °C until use.

The synthesized dsTmAtg6 was diluted to a final concentration of 1.5 µg/µL. dsRNA (1.5 µg/µL) was injected into young-instar larvae (10th–12th instars; n = 30) using disposable needles mounted onto a micro-applicator (Picospiritzer III Micro Dispense System, Parker Hannifin, Hollis, NH, USA). Another set of young-instar larvae (n = 30) were injected with equal amounts of dsEGFP used as a negative control. Injected larvae were maintained on an artificial diet under standard rearing conditions. TmAtg6 knockdown was evaluated and over 90% of knockdown was achieved at 2 days post-injection.

4.7. Survivability Assay

E. coli (106 cells/μL), S. aureus (106 cells/μL), L. monocytogenes (5 × 106 cells/μL), and C. albicans (5 × 104 cells/μL) were prepared according to the protocol as described above. Bioassays were conducted by injecting 1.5 μg/μL dsTmAtg6 into the hemocoel of young larvae. Two days post-injection, the knockdown level was confirmed by qRT-PCR, and prepared microorganisms were injected into both the dsTmAtg6 and dsEGFP–treated larval groups. The challenged larvae were maintained, and the number of living larvae was recorded for 10 days. The survival rates of the TmAtg6-silenced group were compared to those of the control groups. All the experiments were triplicated. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and the cumulative survival ratios were analyzed by Tukey’s multiple test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we identified and characterized the immunological function of TmAtg6 in T. molitor. The induction patterns of TmAtg6 in response to microbial challenges and survivability study confirmed that the TmAtg6 plays a key role against L. monocytogenes infection in T. molitor. We are now focusing on the characterization of the TmAtg6-Atg14L-Vps34-Vps15 complex in autophagosome formation in mealworms during the microbial challenge.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/4/1232/s1.

Author Contributions

Y.S.H. and Y.H.J. conceived and designed the experiments; T.T.E., M.K., K.B.P., J.H.C., Y.M.B. and B.K. performed the experiments; T.T.E. and Y.H.J. and analyzed the data; Y.S.H. and Y.H.J. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; T.T.E. wrote the manuscript; Y.H.J., Y.S.H. and Y.S.L. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Chonnam National University (Grant number: 2017-2919).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mulakkal N.C., Nagy P., Takats S., Tusco R., Juhász G., Nezis I.P. Autophagy in Drosophila: From historical studies to current knowledge. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/273473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lum J.J., DeBerardinis R.J., Thompson C.B. Autophagy in metazoans: Cell survival in the land of plenty. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:439–448. doi: 10.1038/nrm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant B., Raikhel A.S. Programmed autophagy in the fat body of Aedes aegypti is required to maintain egg maturation cycles. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y.P., Liang Z.Q., Gu Z.L., Qin Z.H. Molecular mechanism and regulation of autophagy 1. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005;26:1421–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroemer G., Jäättelä M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:886. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiuri M.C., Zalckvar E., Kimchi A., Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:741. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma V., Verma S., Seranova E., Sarkar S., Kumar D. Selective Autophagy and Xenophagy in Infection and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018;6 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatica D., Lahiri V., Klionsky D.J. Cargo recognition and degradation by selective autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:233. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0037-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaid S., Brandts C., Serve H., Dikic I. Ubiquitination and selective autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:21. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizushima N. Autophagy: Process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamada Y., Funakoshi T., Shintani T., Nagano K., Ohsumi M., Ohsumi Y. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1507–1513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pozuelo-Rubio M. 14-3-3 Proteins are Regulators of Autophagy. Cells. 2012;1:754–773. doi: 10.3390/cells1040754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kihara A., Noda T., Ishihara N., Ohsumi Y. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair U., Cao Y., Xie Z., Klionsky D.J. Roles of the lipid-binding motifs of Atg18 and Atg21 in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway and autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:11476–11488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noda T., Kim J., Huang W.P., Baba M., Tokunaga C., Ohsumi Y., Klionsky D.J. Apg9p/Cvt7p is an integral membrane protein required for transport vesicle formation in the Cvt and autophagy pathways. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:465–480. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geng J., Klionsky D.J. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. ‘Protein modifications: Beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:859–864. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tindwa H., Jo Y.H., Patnaik B.B., Noh M.Y., Kim D.H., Kim I., Han Y.S., Lee Y.S., Lee B.L., Kim N.J. Depletion of autophagy-related genes Atg3 and Atg5 in Tenebrio molitor leads to decreased survivability against an intracellular pathogen, Listeria monocytogenes. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2015;88:85–99. doi: 10.1002/arch.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tindwa H., Jo Y.H., Patnaik B.B., Lee Y.S., Kang S.S., Han Y.S. Molecular cloning and characterization of autophagy-related gene TmATG8 in Listeria-invaded hemocytes of Tenebrio molitor. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2015;51:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y., Klionsky D.J. Physiological functions of Atg6/Beclin 1: A unique autophagy-related protein. Cell Res. 2007;17:839. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kametaka S., Okano T., Ohsumi M., Ohsumi Y. Apg14p and Apg6/Vps30p form a protein complex essential for autophagy in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22284–22291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiki Y., Yoshimoto K., Ohsumi Y. An Arabidopsis homolog of yeast ATG6/VPS30 is essential for pollen germination. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1132–1139. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu X., Yu J., Bhagat G., Furuya N., Hibshoosh H., Troxel A., Rosen J., Eskelinen E.-L., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J. Clin. Investig. 2003;112:1809–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue Z., Jin S., Yang C., Levine A.J., Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15077–15082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang X.H., Jackson S., Seaman M., Brown K., Kempkes B., Hibshoosh H., Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence B.P., Brown W.J. Autophagic vacuoles rapidly fuse with pre-existing lysosomes in cultured hepatocytes. J. Cell Sci. 1992;102:515–526. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine B., Klionsky D.J. Development by self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klionsky D.J. The autophagy connection. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:11–12. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie Z., Klionsky D.J. Autophagosome formation: Core machinery and adaptations. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian Y., Wang M.-L., Zhao J. Crosstalk between autophagy and type I interferon responses in innate antiviral immunity. Viruses. 2019;11:132. doi: 10.3390/v11020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funderburk S.F., Wang Q.J., Yue Z. The Beclin 1-VPS34 complex—At the crossroads of autophagy and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nezis I.P., Vaccaro M.I., Devenish R.J., Juhász G. Autophagy in development, cell differentiation, and homeodynamics: From molecular mechanisms to diseases and pathophysiology. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/349623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry D.L., Baehrecke E.H. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denton D., Shravage B., Simin R., Mills K., Berry D.L., Baehrecke E.H., Kumar S. Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1741–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tettamanti G., Carata E., Montali A., Dini L., Fimia G.M. Autophagy in development and regeneration: Role in tissue remodelling and cell survival. Eur. Zool. J. 2019;86:113–131. doi: 10.1080/24750263.2019.1601271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galluzzi L., Yamazaki T., Kroemer G. Linking cellular stress responses to systemic homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:731–745. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romanelli D., Casartelli M., Cappellozza S., De Eguileor M., Tettamanti G. Roles and regulation of autophagy and apoptosis in the remodelling of the lepidopteran midgut epithelium during metamorphosis. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:32939. doi: 10.1038/srep32939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montali A., Romanelli D., Cappellozza S., Grimaldi A., de Eguileor M., Tettamanti G. Timing of autophagy and apoptosis during posterior silk gland degeneration in Bombyx mori. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2017;46:518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tettamanti G., Grimaldi A., Pennacchio F., de Eguileor M. Lepidopteran larval midgut during prepupal instar: Digestion or self-digestion? Autophagy. 2007;3:630–631. doi: 10.4161/auto.4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tettamanti G., Grimaldi A., Casartelli M., Ambrosetti E., Ponti B., Congiu T., Ferrarese R., Rivas-Pena M.L., Pennacchio F., De Eguileor M. Programmed cell death and stem cell differentiation are responsible for midgut replacement in Heliothis virescens during prepupal instar. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;330:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Sousa M.E.C., Wanderley-Teixeira V., Teixeira Á.A., de Siqueira H.A., Santos F.A., Alves L.C. Ultrastructure of the Alabama argillacea (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) midgut. Micron. 2009;40:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian L., Ma L., Guo E., Deng X., Ma S., Xia Q., Cao Y., Li S. 20-Hydroxyecdysone upregulates Atg genes to induce autophagy in the Bombyx fat body. Autophagy. 2013;9:1172–1187. doi: 10.4161/auto.24731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J.H., Jo Y.H., Patnaik B.B., Park K.B., Tindwa H., Seo G.W., Chandrasekar R., Lee Y.S., Han Y.S. Cloning, expression analysis, and RNA interference study of a HORMA domain containing autophagy-related gene 13 (ATG13) from the coleopteran beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Front. Physiol. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling E., Shirai K., Kanekatsu R., Kiguchi K. Hemocyte differentiation in the hematopoietic organs of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: Prohemocytes have the function of phagocytosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:535–543. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merchant D., Ertl R.L., Rennard S.I., Stanley D.W., Miller J.S. Eicosanoids mediate insect hemocyte migration. J. Insect Physiol. 2008;54:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Y.-R., Lei H.-Y., Liu M.-T., Wang J.-R., Chen S.-H., Jiang-Shieh Y.-F., Lin Y.-S., Yeh T.-M., Liu C.-C., Liu H.-S. Autophagic machinery activated by dengue virus enhances virus replication. Virology. 2008;374:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLean J.E., Wudzinska A., Datan E., Quaglino D., Zakeri Z. Flavivirus NS4A-induced autophagy protects cells against death and enhances virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22147–22159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abernathy E., Mateo R., Majzoub K., Van Buuren N., Bird S.W., Carette J.E., Kirkegaard K. Differential and convergent utilization of autophagy components by positive-strand RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e2006926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colombo M.I., Gutierrez M.G., Romano P.S. The two faces of autophagy: Coxiella and Mycobacterium. Autophagy. 2006;2:162–164. doi: 10.4161/auto.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Py B.F., Lipinski M.M., Yuan J. Autophagy limits Listeria monocytogenes intracellular growth in the early phase of primary infection. Autophagy. 2007;3:117–125. doi: 10.4161/auto.3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campoy E., Colombo M.I. Autophagy in intracellular bacterial infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell Res. 2009;1793:1465–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwon H., Bang K., Cho S. Characterization of the hemocytes in larvae of Protaetia brevitarsis seulensis: Involvement of granulocyte-mediated phagocytosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e103620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moy R.H., Gold B., Molleston J.M., Schad V., Yanger K., Salzano M.-V., Yagi Y., Fitzgerald K.A., Stanger B.Z., Soldan S.S., et al. Antiviral autophagy restrictsRift Valley fever virus infection and is conserved from flies to mammals. Immunity. 2014;40:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shelly S., Lukinova N., Bambina S., Berman A., Cherry S. Autophagy is an essential component of Drosophila immunity against vesicular stomatitis virus. Immunity. 2009;30:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yano T., Mita S., Ohmori H., Oshima Y., Fujimoto Y., Ueda R., Takada H., Goldman W.E., Fukase K., Silverman N. Autophagic control of listeria through intracellular innate immune recognition in drosophila. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:908. doi: 10.1038/ni.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butchar J.P., Cremer T.J., Clay C.D., Gavrilin M.A., Wewers M.D., Marsh C.B., Schlesinger L.S., Tridandapani S. Microarray analysis of human monocytes infected with Francisella tularensis identifies new targets of host response subversion. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amer A.O., Swanson M.S. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:765–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zug R., Hammerstein P. Wolbachia and the insect immune system: What reactive oxygen species can tell us about the mechanisms of Wolbachia–host interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zdobnov E.M., Apweiler R. InterProScan–an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:847–848. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones P., Binns D., Chang H.Y., Fraser M., Li W., McAnulla C., McWilliam H., Maslen J., Mitchell A., Nuka G., et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I.M., Wilm A., Lopez R., et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yaffe H., Buxdorf K., Shapira I., Ein-Gedi S., Moyal-Ben Zvi M., Fridman E., Moshelion M., Levy M. LogSpin: A simple, economical and fast method for RNA isolation from infected or healthy plants and other eukaryotic tissues. BMC Res. Notes. 2012;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.