Abstract

Introduction

Chronic pain is prevalent, and approximately half of patients with chronic pain experience sleep disturbance. Exogenous melatonin is licensed to treat primary insomnia and there is some evidence for analgesic effects of melatonin.

The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of oral melatonin (as Circadin) 2 mg at night in adults with severe non-malignant pain of at least 3 months’ duration.

Methods and analysis

We will conduct a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. The primary outcome is sleep disturbance. Secondary outcomes are pain intensity, actigraphy, fatigue, reaction time testing, serum melatonin and endogenous opioid peptide levels along with patient views about study participation.

We aim to recruit 60 patients with severe chronic pain (average pain intensity ≥7 on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)) from a tertiary referral pain clinic in Northeast Scotland. Participants will be randomised to receive melatonin (as modified release Circadin) 2 mg daily for 6 weeks or placebo, followed by a 4-week washout period, then 6 weeks treatment with the treatment they did not receive. Participants will complete the Verran Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Pain and Sleep Questionnaire 3-item index, BPI and psychomotor vigilance reaction time testing at 6 points over 20 weeks. Actigraphy watches will be used to provide objective measures of sleep duration and latency and other sleep measures and will prompt patients to report contemporaneous pain and fatigue scores daily.

Cross-over analyses will include tests for effects of treatment, period, treatment–period interaction (carryover effect) and sequence. Within-patient effects and longitudinal data will be analysed using mixed linear models, accounting for potential confounders.

Ethics and dissemination

Approved by Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland, reference 19/NI/0007. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and will be presented at national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: pain management, sleep medicine, sleep medicine, pain management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This phase II trial is powered to detect effects of melatonin on subjective sleep disturbance.

The study is limited to a single site in Northeast Scotland.

The randomised cross-over design will expose all participants to the study drug, maximising data available for analysis while reducing the influence of confounding covariates.

We are using only one dose of melatonin (2 mg) for 6 weeks, but there are uncertainties about the optimal dose and dosing duration in our study population.

Longitudinal actigraphy monitoring and daily self-reported outcome measures will improve objectivity, reduce recall bias and enable detailed analysis of within-subject differences.

Introduction

Chronic non-malignant pain is a major clinical problem affecting approximately 20% of the European population.1 Pain and sleep disturbance often occur together. Epidemiological reports suggest that over 50% of individuals with chronic pain experience disturbed sleep.2–5 The risk of poor sleep quality increases as patient-reported pain intensity increases.6 Both chronic pain and sleep disturbance independently diminish quality of life and have a detrimental effect on mental health and well-being.5 Chronic pain and sleep disorders are challenging to manage, and pharmacological options for treating sleep disturbance in individuals with chronic pain are limited.7

Current understanding is that pain and sleep are inextricably linked via a bidirectional relationship: pain disrupts sleep and poor quality or shorter duration of sleep can increase sensitivity to painful stimuli.8 Poor sleep quality and insufficient sleep duration are risk factors for the development of chronic pain.8 9 Neurobiological mechanisms linking sleep and pain are not fully understood but are likely to involve multiple hormonal, chemical and immunological pathways.8 10

Melatonin is a neurohormone, mainly secreted by the pineal gland. Melatonin secretion is stimulated by darkness and suppressed by light, with peak levels occurring between 0200 and 0400 hours. Melatonin is a key regulator of circadian biological rhythms. Meta-analysis shows that treatment of primary sleep disorders with exogenous melatonin reduces sleep latency and improves total sleep time and sleep quality.11 The only licensed form of exogenous melatonin in the EU is a modified release form (Circadin) to treat primary insomnia in adults over the age of 55.12 Immediate release formulations can be prescribed on a named patient basis to treat sleep disorders in children and young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.13

Melatonin has a wide range of functions in addition to its role in the sleep–wake cycle. It is an antioxidant,14 and has anti-inflammatory,15 16 oncostatic17 and anxiolytic properties.18 There is emerging evidence that melatonin also has analgesic effects. The exact mechanisms are not known, but β-endorphins, gamma-aminobutyric acid and opioid receptors, and nitric oxide-arginine pathways have all been implicated.19 Pain sensitivity has a circadian pattern,20 and chronic pain syndromes can be associated with desynchronisation of circadian rhythms.21

There have been many preclinical reports of the benefits of melatonin on pain19 22 23 but few clinical trials in patients. There have been some trials of melatonin in specific types of pain. In patients with fibromyalgia, adjuvant use of melatonin was shown to be useful in reducing the fibromyalgia impact score.24 In patients with migraine, melatonin was as effective at reducing migraine attacks as amitriptyline.25 Our study will determine the effect of melatonin on both sleep parameters and pain in patients with chronic pain of a variety of causes using a cross-over trial to allow within-subject comparisons. Melatonin is a safe and well-tolerated agent, even at high doses.26 It is an accepted therapy for sleep disturbance and indeed Circadin is licensed for insomnia in older subjects. Melatonin could have advantages in the chronic pain population due to its potential to impact both sleep and pain intensity together.

This paper describes the protocol for a phase II randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of exogenous melatonin (as oral Circadin, 2 mg) in patients with severe chronic pain. We consider chronic pain to be pain that has persisted for at least 3 months and define severe pain as self-reported average pain intensity of ≥7 on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). Previous studies of Circadin specifically report efficacy of 2 mg nightly in terms of sleep latency in patients with primary insomnia, with effects seen after 3 weeks.27 28 There is little existing data on the effects of melatonin in patients with chronic pain.

The primary objective is to investigate the effects of exogenous melatonin on sleep in individuals with severe chronic pain. Secondary objectives are to assess the effect of Circadin on pain intensity, activity levels and fatigue. We will also investigate intervention fidelity and pharmacodynamics by measuring serum levels of melatonin and its major metabolite, 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate. We hypothesise that exogenous melatonin will improve sleep duration and quality and reduce pain intensity levels in individuals with chronic pain. We will also investigate the opioid system as a potential pathway of analgesic effect by measuring endogenous opioid peptide levels. We will assess our study procedures for participant acceptability and determine the feasibility of performing a future large-scale multicentre phase II trial.

Methods and analysis

Study design and intervention

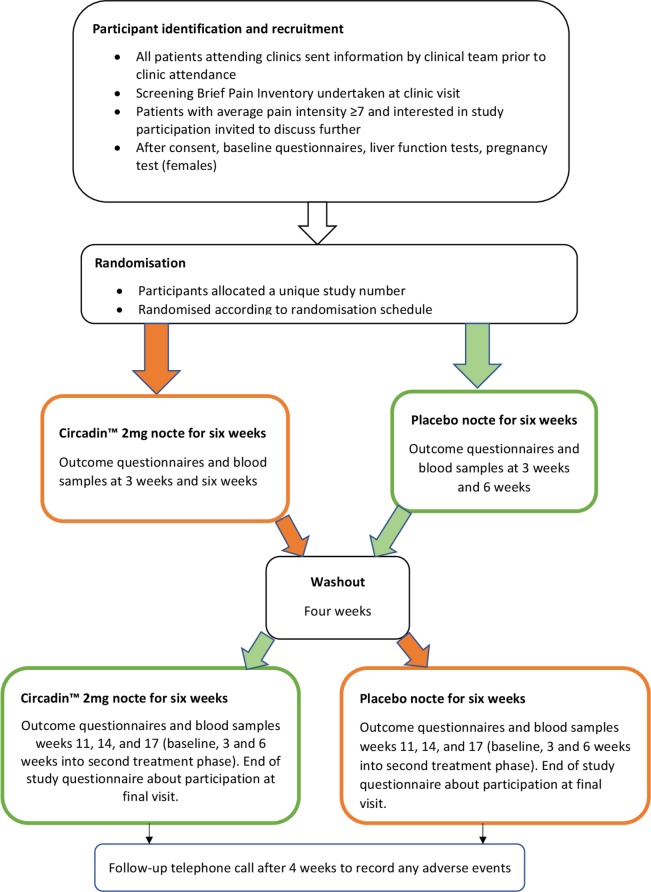

This is a single-centre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase II trial that will recruit patients from a tertiary referral pain management clinic in National Health Service (NHS) Grampian (Northeast Scotland). Participants will be randomised to receive either 2 mg slow release melatonin nightly, as Circadin or an identical placebo for 6 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period and then a further 6 weeks of either placebo or Circadin (whichever they did not initially receive—cross-over design). Participants will be in the trial for a total of 20 weeks. A study flow diagram is presented in figure 1. This protocol paper follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendation for Interventional Trials guidelines.29 We do not plan any modifications to the intervention during the study period. Participants can withdraw at any time. Data and samples obtained will be retained with consent, and any reasons given for withdrawal will be recorded.

Figure 1.

Study participant flow chart.

Sample selection

We will include adult patients (18 years or older) with non-malignant pain of ≥3 months duration who are attending a hospital pain management clinic in NHS Grampian. To be eligible, participants will report severe pain, defined as a self-reported pain score of ≥7 out of 10 on the BPI ‘pain on average’ rating item.30 We will include participants who have been stable on their usual pain medication; changes to medication (doses and type) will not be allowed during the study period. Patients receiving stable doses of duloxetine, gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline or nortriptyline will be included.

Patients taking antidepressants/psychotropic drugs which are not named above will be excluded. We will specifically exclude patients taking serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine or fluvoxamine and individuals taking nifedipine as there are known interactions with melatonin metabolism. We will exclude patients with abnormal baseline liver function tests, since this may affect the metabolism of melatonin. We will exclude patients who are using benzodiazepines or non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (eg, zopiclone, zolpidem, zaleplon) because these medications can affect sleep measures. Similarly, we will exclude individuals with a history of drug or alcohol abuse or post-traumatic stress disorder. We will exclude any woman who is pregnant, breastfeeding or trying to conceive. Individuals with insufficient English to understand trial information/procedures and any patient with known hypersensitivity to Circadin or any of its excipients will be excluded.

Recruitment and consent

Potential participants due to attend pain clinics will be sent letters describing the study by their clinical team with a copy of the participant information sheet. All patients who attend the pain management clinic are routinely asked to complete the BPI on arrival. On arrival at clinic, the outpatient assistant or receptionist will also ask the patients whether they received the study letter and whether they are interested in speaking to their clinician about the study. These patients will be highlighted to the clinical team who will then screen for eligibility. If eligible, interested patients will be asked if they would like to meet with a researcher who will explain the study and take written informed consent. A study visit date will then be arranged for recruited participants to attend the Clinical Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen.

Randomisation, allocation, blinding and data protection

The study team will have no access to participant data or medical records until the potential participant has been identified by the clinical team and has expressed interest in the study. Following eligibility screening and written informed consent, participants will be randomised in blocks of 10 (to minimise seasonal effects) to 1 of 2 groups: melatonin then placebo or placebo then melatonin.

The study drug or an identical placebo will be dispensed from the Clinical Trials Pharmacy, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary according to a previously supplied randomisation code list prepared by an independent statistician not involved in conducting the study. A paper copy of the randomisation code list is locked in a dedicated secure storage area within the Clinical Trials Pharmacy, and an electronic copy is held by the independent statistician on a secure computer server. Participants and all members of the research team will remain blinded to the treatment allocation until after data analysis. Blinding will be maintained unless it is considered necessary to unblind for safety reasons. Participants will be allocated a unique participant identification (ID) number to protect their confidentiality throughout the study, and only the ID number will be used on study documentation. Identifiable patient information will be stored separately in a locked office with restricted access.

Blood samples will undergo secondary randomisation using a computer-generated system by an independent person not involved in the trial and given a unique specimen code so that the sample analyst does not know the participant’s identity, sample number or visit date. This will maintain blinding.

Sample size

The primary outcome measure is improved sleep disturbance, measured using the Verran Snyder-Halpern (VSH) scale,31 which assesses sleep over the previous 24 hours. Our previous study showed that patients with mild pain (average pain score of 4 or less) compared with severe pain (scoring 7 or more) had median VSH sleep disturbance scores of 147 and 490, respectively.6 Assuming a conservative treatment effect difference of 120 (effect size=0.60), we need a minimum of 46 patients to achieve 80% power.

Our main secondary outcome measure is pain intensity. The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials guidelines32 state that the minimum change in pain intensity following an intervention that is clinically relevant is 2 points out of 10. We would need a minimum of 23 patients to demonstrate a change in average pain intensity of 2 points at 80% power. In anticipation of a 30% drop-out rate, we therefore plan to recruit 60 patients, with the aim of retaining 46 patients to trial completion.

Study outcomes

The study outcomes and timings of their assessment are shown in table 1. Participants will have six trial visits—at baseline (week 0); week 3; week 6; baseline after cross-over (after a 4-week washout period, study week 11); 3 weeks after cross-over (study week 14) and 6 weeks after cross-over (study week 17). Participants will be telephoned between each study visit that is, weeks 1, 2, 4, 5 15 and 18, and at 4 weeks after completing the study to ask about any adverse effects.

Table 1.

Summary of outcome assessments and timepoints

| Study visit/timepoint | Week 0 | Period 1 week 3 | Period 1 week 6 | Period 2 week 0 (study week 11) | Period 2 week 3 (study week 14) | Period 2 week 6 (study week 17) |

| Outcome assessment | ||||||

| Demographics | x | |||||

| Serum melatonin | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Serum endogenous opioid | x | x | x | |||

| VSH | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| PSQI | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| PSQ3 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| BPI | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| PVT | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Actimetry data download | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Poststudy questionnaire | x |

BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; PSQ-3, Pain and Sleep Questionnaire 3-item index; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PVT, Psychomotor Vigilance Testing; VSH, Verran Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale.

The primary outcome is sleep disturbance in the last 24 hours, which will be assessed using the VSH sleep scale. We will also assess sleep quality over the last month using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,33 pain-related sleep quality over the past week using the Pain and Sleep Questionnaire 3-item index34 and pain-related sleep interference in the last week using the sleep interference item from the BPI.30 All sleep questionnaires will be conducted at baseline and at every subsequent visit (6 assessments in total over 20 weeks).

Other secondary outcomes are: average pain intensity; activity levels; fatigue; alertness; serum melatonin levels; serum endogenous opioid peptide levels and participants’ views about taking part in the trial.

Average pain intensity will be measured using the BPI, which will be recorded at baseline and at each subsequent visit. We will use actigraphy to measure activity levels and sleep–wake cycle as well as daily patient-reported pain and fatigue ratings. Participants will be provided with the ‘Phillips Spectrum Actiwatch PRO’, a "CE" marked (indicating European Economic Area trading conformity) wrist-worn actimeter, which they will be asked to wear throughout their whole participation in the trial. These devices concur with polysomnography, the gold standard for sleep studies,35 and will also alert participants to rate pain and fatigue on a 0–10-point subjective rating scale at 2000 hours every day. The device has sufficient memory and battery to support continuous recording for 4 weeks, but data will be downloaded at each study visit after baseline.

We will assess reduced alertness due to sleep loss using a personal computer-based psychomotor vigilance test (PVT)36 at baseline and during each subsequent study visit. The PVT requires sustained attention and measures how quickly subjects respond to a visual stimulus. A coloured number appears randomly every few seconds for 2 min and subjects click using an ultrafast gaming mouse as soon as the number appears. The software is freely available to download and incorporates data analysis capability.

Serum melatonin and its active metabolite, 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate will be measured using competitive ELISA at baseline and all subsequent visits. This will give insights into the adequacy of melatonin dosing and participant adherence/intervention fidelity. Endogenous opioid peptide levels will also be measured using ELISA at baseline and a further two study visits to assess potential mechanisms of analgesia associated with melatonin. Blinding will be maintained during all analyses.

Participants will be asked to complete a questionnaire about the trial at the final study visit and will be asked to indicate how onerous participation was using a series of questions and five-point Likert scale with ratings from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Participants will also be asked to indicate whether they thought they knew whether they had melatonin or placebo first and to indicate a percentage improvement in sleep/reduction in pain that would lead them to choose to take melatonin regularly.

Trial status

This trial is currently recruiting. Participant recruitment commenced on 26 July 2019 and is expected to finish recruiting on 8 April 2021. The approved protocol is version 2.0, 6 February 2019.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses will be conducted by Malachy Columb, who is based outside Aberdeen but who is part of the trial team. He will remain blinded to group allocation until after data analysis. Descriptive statistics will be calculated for all relevant variables. The effect of melatonin compared with placebo will be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis with treatment-received and per-protocol analyses as required. Cross-over analyses will include tests for the effects of treatment, period, treatment–period interaction (carryover effect) and sequence. Within-patient effects and longitudinal data will be analysed using mixed linear models and the influences of confounders such as age, sex, numbers and classes of analgesics used will be assessed. Data will be analysed using Number Cruncher Statistical Systems (NCSS) V.11 (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA) and StatXact V.9 (Cytel, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). Significance will be defined at p<0.05 (two sided).

Trial conduct and monitoring

A trial steering committee (TSC) has been set up. The TSC comprises an external expert chair, a local expert and a lay representative. The role of the TSC is to provide oversight for the double-blind randomised controlled trial of exogenous administration of melatonin in chronic pain (DREAM-CP) study on behalf of the trial sponsor and the trial funder and to ensure that the trial is conducted according to the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care and all relevant regulations and local policies. Each TSC member has signed a charter defining roles and responsibilities.

The Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) comprises two external clinical experts and an external statistical advisor. Their remit is to protect and serve DREAM-CP trial participants (especially their safety) and to assist and advise the investigators so as to protect the validity and credibility of the trial. The DMC will safeguard the interests of trial participants, assess the safety and efficacy of the interventions during the trial and monitor the overall conduct of the clinical trial. The DMC are independent from the sponsor. Each member of the DMC have signed a charter.

All adverse events, whether suspected to be treatment related or not, will be recorded. A research governance procedure is in place for reporting of serious adverse events/reactions to the sponsor and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). All adverse events will also be reported to PharSafer. We do not plan to conduct interim analyses of our study data. Trial monitoring is being undertaken by NHS Grampian and a plan has been agreed based on the trial risk assessment. Audit of the clinical trials pharmacy, standard operating procedures and laboratories is overseen by the quality assurance manager.

Patient and public involvement

Patients from the relevant population were involved in the study design stage itself. We shared the participant information sheet with our chronic pain patient liaison group and asked them to comment on both the clarity of the information to be provided and their thoughts about the proposed trial generally. All patients felt the information provided was clear and comprehensive and all said addressing sleep issues was important and they would be happy to take part. We also have lay representation on our trial steering group.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland, reference 19/NI/0007, and NHS Research and Development. The Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) reference is 255612. The study is a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medical Product and a clinical trial authorisation was granted by MHRA reference 21583/0223/001–0001. Our results will be disseminated at relevant scientific meetings and published in a peer-reviewed journal. We will produce a poster displaying our results which will be displayed in the waiting area of the chronic pain clinic and posted to all participants. The study team also plan to disseminate results via local public engagement events organised by University of Aberdeen.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RA contributed to the grant proposal and writing the protocol and is involved in aspects of the day-to-day running of the trial. SK is the chief investigator. He was involved in the conception of the trial and contributed to trial design. He is involved in the day-to-day running of the trial. UO is a research assistant who is responsible for recruitment and conduct of trial visits and undertaking laboratory analyses. MC undertook sample size calculations, contributed to the protocol and other trial documents and will undertake statistical analyses. HG conceived of the trial, drafted the protocol and other trial document, and is overseeing all aspects of the study.

Funding: This work was supported by a project grant from British Journal of Anaesthesia/Royal College of Anaesthetists, administered by the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia under grant number WKR0-2017-0043. This study is cosponsored by the University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian. Melatonin and placebo were supplied free of charge by Flynn Pharma Ltd. Neither the funders, the sponsor nor Flynn Pharma Ltd had any input into the design of this study and will have no role in data analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karaman S, Karaman T, Dogru S, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbance in chronic pain. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18:2475–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marin R, Cyhan T, Miklos W. Sleep disturbance in patients with chronic low back pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006;85:430–5. 10.1097/01.phm.0000214259.06380.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MT, Perlis ML, Smith MS, et al. Sleep quality and presleep arousal in chronic pain. J Behav Med 2000;23:1–13. 10.1023/A:1005444719169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev 2004;8:119–32. 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00044-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaughan R, Galley H, Kanakarajan S. Assessment of sleep in patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth 2018;120:e10 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network., Scotland Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Management of chronic pain : a national clinical guideline. Available from. Available: http://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-136-management-of-chronic-pain.html

- 8.Haack M, Simpson N, Sethna N, et al. Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45:205-216 [Epub ahead of print] 10.1038/s41386-019-0439-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afolalu EF, Ramlee F, Tang NKY. Effects of sleep changes on pain-related health outcomes in the general population: a systematic review of longitudinal studies with exploratory meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2018;39:82–97. 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152:S2–15. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-Analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One 2013;8:e63773 10.1371/journal.pone.0063773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BNF: British National Formulary - NICE.. Available: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/melatonin.html [Accessed cited 2019 Aug 2].

- 13.NICE About melatonin | information for the public | sleep disorders in children and young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: melatonin | advice |. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/esuom2/ifp/chapter/About-melatonin [Accessed cited 2019 Aug 1].

- 14.Hardeland R. Antioxidative protection by melatonin: multiplicity of mechanisms from radical detoxification to radical avoidance. Endocrine 2005;27:119–30. 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Tan D-X, et al. Anti-Inflammatory actions of melatonin and its metabolites, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK) and N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK), in macrophages. J Neuroimmunol 2005;165:139–49. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrillo-Vico A, Guerrero JM, Lardone PJ, et al. A review of the multiple actions of melatonin on the immune system. Endocrine 2005;27:189–200. 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panzer A, Viljoen M. The validity of melatonin as an oncostatic agent. J Pineal Res 1997;22:184–202. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1997.tb00322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comai S, Gobbi G. Unveiling the role of melatonin MT2 receptors in sleep, anxiety and other neuropsychiatric diseases: a novel target in psychopharmacology. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2014;39:6–21. 10.1503/jpn.130009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaur T, Shyu B-C. Melatonin: a new-generation therapy for reducing chronic pain and improving sleep disorder-related pain. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018;1099:229–51. 10.1007/978-981-13-1756-9_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagenauer MH, Crodelle JA, Piltz SH. The modulation of pain by circadian and Sleep-Dependent processes: a review of the experimental evidence. bioRxiv 2017:098269. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caumo W, Hidalgo MP, Souza A, et al. Melatonin is a biomarker of circadian dysregulation and is correlated with major depression and fibromyalgia symptom severity. J Pain Res 2019;12:545–56. 10.2147/JPR.S176857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Shenawy SM, Abdel-Salam OME, Baiuomy AR, et al. Studies on the anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive effects of melatonin in the rat. Pharmacol Res 2002;46:235–43. 10.1016/S1043-6618(02)00094-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galley HF, McCormick B, Wilson KL, et al. Melatonin limits paclitaxel-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro and protects against paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain in the rat. J Pineal Res 2017;63:e12444 10.1111/jpi.12444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain SA-R, Al-Khalifa II, Jasim NA, et al. Adjuvant use of melatonin for treatment of fibromyalgia. J Pineal Res 2011;50:267–71. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:1127–32. 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galley HF, Lowes DA, Allen L, et al. Melatonin as a potential therapy for sepsis: a phase I dose escalation study and an ex vivo whole blood model under conditions of sepsis. J Pineal Res 2014;56:427–38. 10.1111/jpi.12134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemoine P, Garfinkel D, Laudon M, et al. Prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia - an open-label long-term study of efficacy, safety, and withdrawal. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2011;7:301–11. 10.2147/TCRM.S23036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemoine P, Zisapel N. Prolonged-release formulation of melatonin (Circadin) for the treatment of insomnia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:895–905. 10.1517/14656566.2012.667076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200 A 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994;23:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyder-Halpern R, Verran JA. Instrumentation to describe subjective sleep characteristics in healthy subjects. Res Nurs Health 1987;10:155–63. 10.1002/nur.4770100307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005;113:9–19. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayearst L, Harsanyi Z, Michalko KJ. The pain and sleep questionnaire three-item index (PSQ-3): a reliable and valid measure of the impact of pain on sleep in chronic nonmalignant pain of various etiologies. Pain Res Manag 2012;17:281–90. 10.1155/2012/635967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marino M, Li Y, Rueschman MN, et al. Measuring sleep: accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of wrist actigraphy compared to polysomnography. Sleep 2013;36:1747–55. 10.5665/sleep.3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khitrov MY, Laxminarayan S, Thorsley D, et al. PC-PVT: a platform for psychomotor vigilance task testing, analysis, and prediction. Behav Res Methods 2014;46:140–7. 10.3758/s13428-013-0339-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.