Abstract

This study systematically reviewed the methodology and findings of 19 peer-reviewed studies on the experience of bereavement among widowed Latinos, including risk and protective factors to the health of this vulnerable population. Of these studies, 10 included quantitative data, 3 were qualitative studies, and 6 were narrative reviews. Results emphasized the relevance of cultural beliefs about death, rituals, religion, and Latino values (i.e., familismo, respeto, simpatía, personalismo) as common themes in the included studies, along with expressions of grief (e.g., Ataque de nervios, somatization) that vary by gender and acculturation. Risk factors associated with diminished well-being in this population included being a male, financial strain, cultural stressors, having an undocumented legal status, experiencing widowhood at a younger age, and having poor physical health. Effective coping strategies identified included having adequate social support primarily from family, religion and religious practices, the use of folk medicine, volunteering, and the use of emotional release strategies. Moreover, the results highlight that researches informing the health needs of widowed Latinos in the US is limited, and studies with enhanced methodological rigor are needed to better understand the complex needs of this vulnerable population.

The death of a spouse is a common experience in older adulthood, and it is an extremely stressful event that varies extensively from person-to-person (Bartrop, 2017). In 2017, approximately 3.3 million men and 11.6 million women in the United States (US) were widowed, with the majority of these being 65 years and older (US Census Bureau, 2017). Demographic trends in the US show a marked increase in Latino elders over the next half-century, with Latino elders comprising up to 20% of the US elderly population by 2050 (Vincent & Velkoff, 2010). It is estimated that the US Latino elderly population will grow from 2.9 million in 2010 to 17.5 million by 2050, a more than six-fold increase (Vincent & Velkoff, 2010). Given the aforementioned trends in the Latino population and the high prevalence of widowhood among the elderly, developing a better understanding of the bereavement process and related health outcomes among Latinos facing widowhood is warranted.

Bereavement is a period of grief, transition, and adjustment, and although a large proportion of bereaved individuals are resilient and eventually adjust to the grieving process (MacLeod, Musich, Hawkins, Alsgaard, & Wicker, 2016), the severe psychological stress experienced by the bereaved can have significant health consequences (Stahl & Schulz, 2014). Indeed, bereavement is associated with diminished health outcomes, including increased risk of mortality and illness, higher cardiovascular risk, disability, diminished functioning, and symptoms of psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, anger) (Buckley, McKinley, Tofler, & Bartrop, 2010; Lee & Carr, 2007; MacLeod et al., 2016). Moreover, bereavement is characterized by poor or harmful health behaviors that are associated with diminished well-being such as altered sleep patterns, increased alcohol consumption, and poor nutrition due to diminished appetite and involuntary weight loss (Stahl & Schulz, 2014). Also, a few studies suggest that diminished physical activity and its associated negative health effects may also be prevalent in bereavement (Stahl & Schulz, 2014). Nonetheless, despite widespread evidence documenting the effect of bereavement across various health outcomes and health behaviors, information about the bereavement process and related vulnerabilities among Latinos is limited.

Widowhood is particularly distressing in the face of social disadvantage, which is prevalent among elderly Latinos (National Hispanic Council on Aging, 2017). In accord with existing conceptual models, individuals facing social disadvantage are exposed to more chronic stressors with less access to resources (e.g., healthcare, social services) that those with less social disadvantage, which may result in diminished health outcomes (Gallo, Smith, & Cox, 2006; Gallo, Bogart, Vranceanu, & Matthews, 2005). Compared to other ethnic/racial groups, Latinos have a high prevalence of stress associated to social disadvantage from poverty, lower social standing, limited social mobility, cumulative deprivation, and discrimination (Garza, Glenn, Mistry, Ponce, & Zimmerman, 2017; Morales, Lara, Kington, Valdez, & Escarce, 2002; Mulia, Ye, Zemore, & Greenfield, 2008). Particularly at-risk are Latino elders who are often faced with financial burden, functional limitations, and limited access to social and healthcare resources (National Hispanic Council on Aging, 2017). It is likely that the aforementioned vulnerabilities along with social disadvantages experienced over an extended time may render Latino elders at greater risk for negative health outcomes during and after bereavement. Further understanding of the bereavement process among widowed Latinos, particularly those facing social disadvantage, is needed to inform the development of intervention and prevention efforts, as well as advocacy and health policy.

Effective risk and resilience factors are integral in alleviating many of the adverse effects of bereavement, with individual perceptions, social contexts, and membership to a cultural/ethnic group playing an important role in the coping process (Lawson, 1990). The cultural and contextual factors that may lead to less grief and an easier adjustment across ethnic/racial groups are critical to our understanding of bereavement. For instance, there are notable differences in coping with bereavement across ethnic/racial groups with strong variations in the intensity of the grief process based on cultural beliefs (Clements et al., 2003). Further understanding of the effect of culture in coping with bereavement among widowed Latinos is essential to reduce disease risk in this vulnerable population about which little is known, while also identifying protective factors that could foster resilience from culture and context-sensitive perspective.

Purpose of review

This study aimed to systematically review the methodology and findings of scientific studies and reviews of bereavement among widowed Latinos in the US. Specific aims of this review are to: (a) describe the population and setting characteristics, as well as the methodology used; (b) summarize findings, themes/constructs assessed, and outcomes in the included studies; and (c) provide recommendations for future studies.

Methods

The methodology used in this review is based on guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Liberati et al., 2009). The present study includes scientific studies reporting quantitative and/or qualitative data, as well as narrative reviews on the topic. Inclusion criteria for quantitative studies was that the study: (a) was published in English or Spanish; (b) clearly specified the inclusion of Latinos in the US; and (c) included the assessment of health indicators, coping, and/or an associated psychosocial risk or protective factor among widowed Latinos in the US. Similarly, inclusion criteria for qualitative studies were that the study was published in English or Spanish, included Latinos in the US, and focused on or explored the experience of widowhood. For studies or reviews reporting data on different bereaved populations including widowhood, only the data relevant to widowhood were analyzed and included in this review. Also excluded were measurement development articles, presentations of clinical/counseling guidelines.

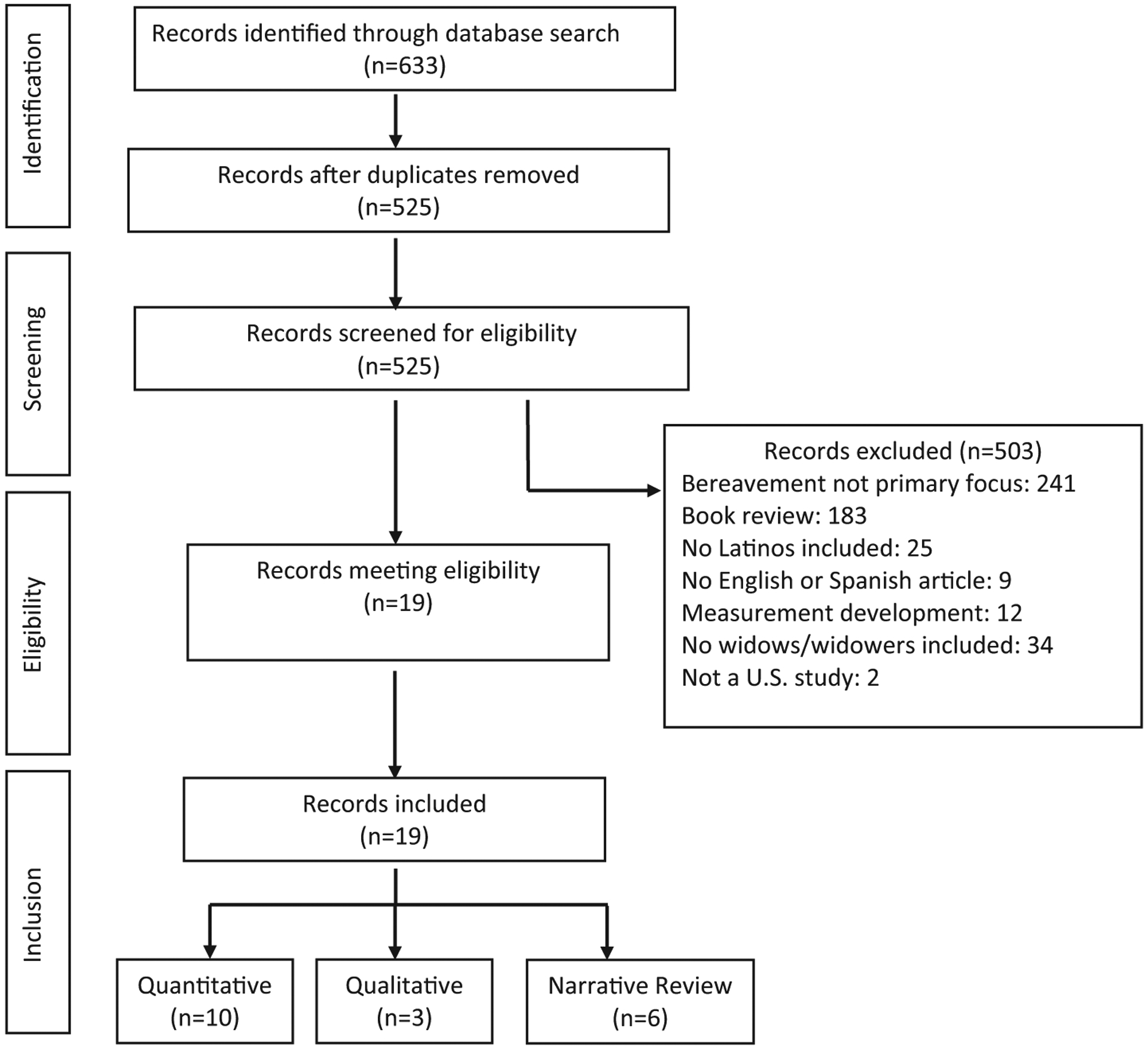

For the initial selection of studies, a literature search using multiple databases (i.e., Academic Search Premier, CINAL, ERIC, Medline, and PsycInfo) was done. Relevant articles searches were limited to peer-reviewed studies and narrative reviews, and the last search was conducted in January, 2018. Terms selected for the search were bereave* OR grief* OR griev* OR mourn* OR widow*AND Latin* OR Hispanic*. A total of 633 articles were identified. Following the removal of duplicates (n = 108), 525 articles were screened for inclusion. Titles, abstracts, and in some cases the complete text were reviewed for eligibility. From the articles reviewed, 19 articles met eligibility criteria and are included in this review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of article screening and eligibility.

A standardized data abstraction form was created for the coding of the selected articles. Information on study design and methodology, the purpose of study, sample characteristics, themes/constructs assessed, measures used, a summary of findings/comments, and limitations of the study was abstracted from eligible studies. Modifications were made to the coding sheet by two coders until 93% inter-rater joint probability agreement was obtained, and each eligible study was coded independently by one of two coders.

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 19 studies included, three were qualitative, 10 were quantitative, six were narrative reviews by experts in the field, and none used mixed-methods (see Table 1). Among qualitative studies, data were collected either through focus groups or face-to-face interviews. One qualitative study presented a case study. Among qualitative studies that provided details on methodology, concept and thematic analyses were used. None of the qualitative studies reported a response rate. Pertaining to quantitative studies, most were longitudinal (6 of 10), with the rest being crosssectional. Most longitudinal studies (4 of 6) included at least three time-point assessments with a minimum of a year and a half follow-up. Also, four quantitative studies used original data, two used data from identifiable databases, and three did not report their data source. Overall, recruitment methods across studies were not commonly reported. Nonetheless, among studies reporting on their recruitment methods, four studies used random sampling, specifically, three used area probability sampling, and one used stratified sampling. Other methods of recruitment included flyers, recruitment from group settings such as church meetings or workplaces, snowball sampling, and/or contact lists from community agencies. Pertaining to the mode of data collection, nine studies used self-report and one did not report how data was collected. Data were primarily collected using surveys or interviews administered in-person or over the phone. Only one quantitative study out of 10 studies reported a response rate, which was 81%. Among the few quantitative studies that reported where data was collected, most were done in the southwest US (4 of 10).

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Study | Data source | Year of data collection | Study design | Location for data collection | Response rate | Mode of data collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angel, Jimenez, and Angel (2007) | Health and retirement study | 1992–2000 | Longitudinal | National | 81% | Face-to-face interview/survey |

| Angel et al. (2003) | H-EPESEa | NR | Longitudinal | TX, CA, NM, AZ, CO | NR | Face-to-face interview/survey |

| Balkwell (1985) | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | CA | NR | Face-to-face interview/survey |

| Bravo (2017) | NR | 2013 | Qualitative | NC, NY | NR | Interview |

| Clements et al. (2003) | NA | 2003 | Narrative review | NA | NA | Narrative review |

| Cowles (1996) | Primary | NR | Qualitative | NR | NR | Thematic review of focus groups |

| Diaz-Cabello (2004) | Primary | NR | Qualitative | NR | NR | Case study |

| Hodges, Dunn, Wagner, and Royall (2005) | Primary | NR | Cross-sectional | NR | NR | NR |

| Eisenbruch (1984a) | NA | 1984 | Narrative review | NA | NA | Narrative review |

| Eisenbruch (1984b) | NA | 1984 | Narrative review | NA | NA | Narrative review |

| Grabowski and Frantz (1993) | Primary | NR | Cross-sectional | NY | NR | Face-to-face interview/survey |

| Hardy-Bougere (2008) | NA | 2008 | Narrative review | NA | NA | Narrative review |

| Ide et al. (1990) | Primary | 1984–1986 | Longitudinal | AZ | NR | NR |

| Ide et al. (1992) | Primary | 1984–1986 | Longitudinal | AZ | NR | NR |

| Kay et al. (1988) | Primary | 1987 | Longitudinal | AZ | NR | Face-to-face interview/survey |

| Morgan (1976) | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | NR | NR | Interview |

| Munet-Vilaro (1998) | NA | NA | Narrative review | NA | NA | Narrative review |

| Schoulte (2011) | NA | 2011 | Narrative review | NA | NA | Narrative review |

| Wagner (1993) | Primary | NR | Longitudinal | CA | NR | Face-to-face interview |

Note: Primary data source refers to data collected firsthand for the specific purpose of the study. NA: not applicable; NR: not reported.

Hispanic established population for the epidemiological study of the elderly.

Participant characteristics

Overall, four studies consisted exclusively of Latino participants, with the rest also including participants from other ethnic/racial backgrounds (see Table 2). Of the four studies focused solely on a Latino sample, most participants were of Mexican–American origin. Also, seven studies included bereaved participants only, whereas the rest of the studies included mixed samples of bereaved and non-bereaved individuals. Most studies provided limited information on the sample characteristics, particularly qualitative studies and studies including mixed samples in terms of ethnicity and bereavement status, which limited comparisons across studies in key demographics. Furthermore, among studies reporting on gender for bereaved Latinos (n = 11), all included a greater percentage of women than men. Of these, six studies included an all-female sample and none included all-males. Also, participants varied greatly in age ranges across studies, from young adults to elders, and most studies were limited in reporting mean or median data for age. Among the studies that reported on education (n = 5), most included samples with low educational attainment (65–96% < high school). Additionally, among the studies that reported income (n = 7), all were of low income. No studies provided information for length of the relationship with deceased spouse/partner, and only four studies provided any description of time since death, which varied considerably.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics for qualitative and quantitative studies.

| Study | Sample size (n) (% Latino, % Widowed Latino) | Participant characteristics (age, gender) | Socio-economic status (income, education) | Length of relationship | Time since death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angel et al. (2007) | n = 4076 Latino: 8.7%, Widowed Latino: 8.4% | Age rangea: NR (M = 55.5) Sex: 100% female | Income M=$26,622/year High school: 64.7% | NR | NR |

| Angel et al. (2003) | n = 356 Latino: 100% Widowed Latino:100% | Age range ≥ 65 years (M=NR) Sex: 80.9% female | Income: NR High school: 95.7% for males; 92.8% for females | NR | “Newly widowed” |

| Balkwell (1985) | n = 272 Latino: 34.6% Widowed Latino: 100% | Age range: 45–75 years (M=NR) Sex: 84% female | Income: NR High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Bravo (2017) | n = 12 Latino: 100% Widowed Latino: NR | Age range: NR (M=NR) Sex: NR | Income: NR High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Cowles (1996) | n = 35 Latino: 26% Widowed Latino: 100% | Age range: 21–83 years (M=NR) Sex: 71% female. | Income: NR High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Diaz-Cabello (2004) | n = 3 Latino: 100% Widowed Latino: NR | Age range: NR (M=NR) Sex: NR | Income: NR High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Hodges et al. (2005) | n = 90 Latino: 100% Widowed Latino: 100% | Age range: 65–79 years (M=NR) Sex: 100% female | Income: low High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Grabowski & Frantz (1993) | n = 100 Latino: 50% Widowed Latino: 100% | Age range: NR (M = 47) Sex: 69% female | Income: NR High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Ide et al. (1990) | n = 117 Latino: 45.3% Widowed Latino: 100% | Age range ≥ 40 years (M=NR) Sex: 100% female | Income <$6000/year (56%) High school: 86% | NR | Baseline: 1–6 months since death |

| Ide et al. (1992) | n = 117 Latino: 45.3% Widowed Latino: 100% | Age range ≥ 40 years (M=NR) Sex: 100% female | Income <$6000/year (56%) High school: 86% | NR | Baseline: 1–6 months since death |

| Kay et al. (1988) | n = 113 Latino: 47% Widowed Latino: NR | Age range > 40 years (M=NR) Sex: 100% female | Income <$6000/year (56%) High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Morgan (1976) | n = 595 Latino: NR Widowed Latino: NR | Age range: 45–74 years (M=NR) Sex: 100% female | Income rangeb: $2000–$25,000/year High school: NR | NR | NR |

| Wagner (1993) | n = 232 Latino: 58% Widowed Latino: 6.2% | Age range > 30 years in 31.5% of Latinos (M=NR) Sex: 100% female | Income <$10,000/year (78%) High school: 64.6% | NR | >2 years |

NR: Not reported.

Overall data, not specific to Latinos and/or bereaved.

Ethnic data not provided.

Findings from qualitative studies and narrative reviews: Relevant themes and vulnerabilities

Cultural beliefs about death, rituals, and religion were identified as common themes among qualitative studies and narrative reviews (See Table 3). For instance, continued bond with the deceased or thinking of death as an extension of life was identified as a prevalent belief among Latinos, which often facilitates the coping process. These studies emphasized that continuity of relationship with the deceased is a powerful belief that guides grieving behaviors and rituals aimed to convey the idea that the deceased has moved onto a different life phase, but his/her spirit continues to be present. Moreover, the relevance of rituals as coping factors was emphasized as relevant among widowed Latinos. For instance, popular celebrations and practices such as Día de Muertos, a celebration in remembrance of the deceased to help support their spiritual journey, and the Novena, a prayer practice held over nine days after a death, highlight the relevance of continued bond with the deceased as a way of coping with the loss. Elaborate wakes and funerals, sometimes held at the home of the deceased, were also emphasized as important social events attended by a large network of family and friends to share memories. Furthermore, religiosity emerged as a protective factor that facilitates the coping process. While religious beliefs and preferences vary across Latino groups, Catholicism is the dominant religion (Clements et al., 2003). Specifically, religious rituals (masses, rosaries, and novenas) were identified as helpful by validating and reinforcing values, facilitating the expression of feelings, and the promotion of group ties and interactions (Eisenbruch, 1984b; Munet-Vilaro, 1998). One narrative review emphasized that religious rituals and celebrations can help survivors in the search of inner peace in the grief process, which exemplifies the belief of the unity between life and death (Diaz-Cabello, 2004). Moreover, the spiritual and physical relationship between the living and the deceased usually consists of prayer, which emphasizes both the continued bond with the deceased and the importance of religiosity in bereavement (Clements et al., 2003).

Table 3.

Identified themes in qualitative studies and narrative reviews (n = 9).

| Study | Cultural beliefs about death | Expressions of grief | Social conventions | Stressors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group differences | Continued bond | Religion | Rituals | Overall | Gender | Acculturation | Cultural values | Social support | Cultural differences | Economic stress | Legal status | |

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 7 | n = 2 | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 5 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 1 | |

| 70% | 60% | 70% | 60% | 80% | 20% | 20% | 30% | 60% | 10% | 10% | 10% | |

| Bravo (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Clements et al. (2003) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Cowles (1996) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Diaz-Cabello (2004) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Eisenbruch (1984a) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Eisenbruch (1984b) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hardy-Bougere (2008) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Munet-Vilaro (1998) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Schoulte (2011) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

Another common theme among qualitative studies and narrative reviews was the emphasis on Latino cultural values as protective factors and driving forces underlying social convention in bereavement. For instance, familismo, the deep feelings of dedication, commitment, and loyalty to the family emerged as an important value that facilitates support from the nuclear and extended family throughout the grieving process, including providing valuable sources for consultation, decision making, and problem solving during this difficult life transition (Schoulte, 2011). Also, given that the Latino family encompasses a broad network that often includes non-blood kin considered part of the extended family, large and crowded gatherings are expected to precede and/or after death and are frequently perceived as desirable sources of emotional and instrumental support (Schoulte, 2011). Another important value identified was respeto, which refers to the rules that guide social relationships that adhere to a hierarchical structure based on age and gender. For example, respeto was identified as particularly relevant in the provision of healthcare and counseling services to bereaved Latinos (Clements et al., 2003). Two additional values identified as important were simpatía, the significance of politeness and diplomacy in relationships, and personalismo, the value of interpersonal warm, kindness and affection, which are usually abound in interactions with and around the bereaved and facilitates interpersonal interactions during this stressful time (Schoulte, 2011).

Emotional expression and experience of stress

Expressions of grief also emerged as a prevalent theme with variations by gender and acculturation. Overall, open expressions of grief such as crying are viewed as acceptable among women, but not necessarily perceived as a norm for men given that men are expected to be strong and to contain their emotions. Ataque de nervios, a syndrome characterized by strong emotional reactions (e.g., seizure-like patterns, uncontrollable sobbing/yelling, fainting) in the face of a distressing event, was also identified as a common expression of grief among Latina women, particularly those of Caribbean origin (Eisenbruch, 1984b). In addition, hugging and touching a grieving person was identified as a desirable, supportive gesture. Praying was also ascertained as a common expression of grief regardless of gender. Acculturation differences in the expression of grief were highlighted in a few studies, with lower acculturation reflecting stronger adherence to traditional Latino grieving rituals.

Finally, one of the narrative reviews included highlighted potential stressors that may complicate bereavement (Eisenbruch, 1984b). This includes economic stress that results from expenses related to the funeral, as well as the financial strain of needing to spend time away from work. Cultural stressors were also addressed as factors likely to increase distress during bereavement, given the ambivalence between Latino and American culture that may affect one’s ability to embrace one’s cultural practices in bereavement. Moreover, one qualitative study addressed the impact of having an undocumented immigration legal status while coping with transnational bereavement, which may lead to feelings of guilt for being unable to be in close proximity to the family during the difficult times (Bravo, 2017). The aforementioned study highlighted the relevance of information technology as a valuable resource for immigrants to create an illusion of being physically present when they are unable to travel to their country of origin.

Findings from quantitative studies: Risk and resilience factors

Psychological and physical symptoms, health outcomes, risk factors, and coping strategies were the primary focus of quantitative studies. Pertaining to symptoms and health outcomes, 4 of 10 studies reported on prevalent psychological symptoms among widowed Latinos, including identifying differences across ethnicities. For instance, a study showed a greater prevalence of forgetfulness, nervousness, boredom, hopelessness, and feeling that life was too hard among widowed Latinos, while feelings of loneliness, sadness, and fatigue were more prevalent among their White counterparts (Kay et al., 1988). Also, somatization was identified as an appropriate idiom to express distress (4 of 10 studies).

Risk factors

Furthermore, 9 of the 10 studies identified various risk factors for diminished well-being among widowed Latinos. In these studies, socio-economic vulnerabilities, particularly being male (Angel, Douglas, & Angel, 2003), experiencing widowhood at a younger age (Morgan, 1976), and experiencing financial strain (Ide, Tobias, Kay, & de Zapien, 1992; Kay et al., 1988) were associated with diminished well-being. Of note, one study identified employment as an important protective factor associated with better morale among Latina widows (Morgan, 1976). Other risk factors associated with diminished well-being were poor physical health and perceptions of symptom severity. In addition, findings were mixed for the effect of acculturation on well-being, with one study finding greater acculturation to be associated with fewer symptoms and greater functioning, whereas another study found no association between acculturation and grief intensity (Grabowski & Frantz, 1993). Pertaining to characteristics of death, two studies found no association between time since spousal death, grief intensity, and long-term effect on morale (Balkwell, 1985; Grabowski & Frantz, 1993). Nonetheless, type of death emerged as a salient risk factor, with sudden death being associated with greater grief intensity when compared to expected death (Grabowski & Frantz, 1993). Of note, only one study explored the association between the quality of the relationship, specifically closeness with spouse/partner, and grief intensity; however, findings were non-significant (Grabowski & Frantz, 1993).

Resilience factors

Resilience factors and related strategies (i.e., social support, religion/religious practices, folk medicine, volunteering, and coping style) were the focus of 8 of 10 quantitative studies. Of these, most studies evaluated the effect of social support on adjustment to bereavement (i.e., morale), health outcomes (i.e., physical symptoms, depression), and help-seeking behaviors (i.e., counseling) among widowed Latinos. Overall, these studies supported a positive association between social support and the aforementioned outcomes, with family members and widowed peers identified as key providers of emotional and instrumental support. Noteworthy, one study identified important gender differences in receiving social support during bereavement, specifically instrumental support, with Latina widows receiving more support than their male counterparts (Angel et al., 2003). Pertaining to religion, devoutness was found to be significantly associated to adjustment (Angel et al., 2003; Kay et al., 1988), although relevant gender differences emerged with Latina widows being more likely to find comfort in church attendance than Latino widowers (Angel et al., 2003). In addition to the aforementioned resilience factors and coping strategies, folk medicine emerged as culturally-relevant in coping with bereavement and preferred over traditional medicine. For instance, one study found that although 15% of Mexican–American widows were prescribed tranquilizers after spousal loss, only 5% took the medication more than once and instead preferred the use of different folk remedies (e.g., Te de Manzanilla, Te de Azahar) (Kay et al., 1988).

Moreover, 3 of 10 studies evaluated the effects of coping style on health outcomes in bereavement, specifically long-term health effects and symptoms of depression. For instance, a combination of emotional release strategies and independent action; that is, planned activities conducted to accomplish a goal, was identified as an effective coping strategy among Mexican-American widows when compared to their White counterparts (Ide, Tobias, Kay, Monk, & de Zapien, 1990). Also, one study found that when compared to White widows, Mexican–American widows avoided the use of counseling services and support groups (Kay et al., 1988).

Discussion

We evaluated study designs, methodology, participant characteristics, construct themes and findings of 13 studies and six narrative reviews of bereavement among widowed Latinos.

After assessing the methods and characteristics of the participants in the included studies, we found various methodological weaknesses in these studies, which span across a wide range of dates of publication. Indeed, there are numerous selection and information biases in the included studies that are important to address, and which reflect a need for greater scientific and methodological rigor within this field. For instance, most of the included studies were limited in reporting information necessary to assess the quality of the study design, response rates, representativeness of the sample, and the validity of findings. This information is essential to contextualize study findings and bridge the gap between research and its practical applications. Also, sound reporting of recruitment methods is important given that bereavement is a difficult life transition that can make the recruitment process difficult. Future studies could benefit from learning what techniques might be particularly effective in the recruitment and retention of bereaved Latinos, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds including those living in poverty, those with lower acculturation, sexual minorities, and those with undocumented immigration legal status, among others. Of note, the majority of studies focused on widows exclusively, which highlights the need for future studies that can provide a further understanding of the bereavement process among Latino widowers, while also facilitating comparisons across gender. Likewise, most studies consisted of participants of Mexican–American origin, and although this is an important population to study, there is a need for studies that would inform the bereavement process from an ethnic perspective in general while also informing differences among Latino subgroups (e.g., acculturation differences, countries of origin). This information would be helpful to identify what factors may be extrapolated to the experiences of the Latino culture in general, while also identifying specific variations important to consider in the adaptation and individualization of treatment. In short, this review highlights an urgent need for stronger research designs, larger and more varied samples, and the use of better assessment methods as a way to improve the quality of health research among Latinos facing spousal bereavement.

Despite the aforementioned methodological weaknesses, our results support that, although grief is a universal human experience, mourning is influenced by cultural beliefs, practices, and values. Emphasizing the relevance of the aforementioned cultural aspects to the bereavement experience among widowed Latinos is essential in the provision and development of culture-sensitive practices, assessments, and interventions aimed at facilitating the coping process during this difficult life transition. Important to emphasize is that Latinos vary greatly in their adherence to traditional beliefs and values; thus, future research needs to account for such variations while also identifying common ground to inform the development of effective interventions. For instance, familismo, which often entails emphasizing the interest of the family group over individual interests, continues to be one of the most important values for Latinos (Landale, Oropesa, & Bradatan, 2006). However, factors such as increasing divorce rates, family separation due to deportation, migration and/or relocation, generational gaps among family members, and shifting gender roles among other influences, are contributing to make Latino families more heterogeneous in their interpersonal dynamics and endorsement of familismo (Landale et al., 2006). The provision of culturally and contextually sensitive grief interventions to Latino families requires the training of providers sensitive to address complex cultural shifts that may present among family members and how these shifts may influence the grieving process. Manifestations of the aforementioned cultural shifts may include variations among family members in the endorsement and practice of spiritual beliefs, mourning rituals, expressions of grief, family roles, and symptom presentation. Future research should focus on facilitating an understanding of how cultural shifts among family members may influence the bereavement experience.

This review also identified risk factors for diminished well-being among widowed Latinos. Consistent with the general bereavement literature, socio-economic, demographic, and health vulnerabilities were associated with increased health risk in this population (Balkwell, 1985; Yochim & Woodhead, 2017). As previously mentioned, salient within-group differences in the expression of grief, such as those attributed to gender, are important to consider. For instance, although a vast amount of research supports gender differences in the expression of emotion, these differences can be magnified by cultural gender norms such as those prevalent in the Latino culture (Miville, Mendez, & Louie, 2017). For instance, crying is openly accepted as a healthy response among bereaved Latinos; however, men are more likely than women to suppress crying or to cry in private. Prevalent values such as machismo, the need to present oneself as strong and masculine, even in the face of bereavement, may preclude Latino widowers from expressing sorrow and/or seeking grief counseling, which in turn could increase distress and its associated negative health outcomes (Sobralske, 2016). Additional studies are needed to explore how existing gender norms may influence the expression of grief among bereaved Latinos, and how such dynamics may promote or hinder well-being. Likewise, studies that can facilitate an understanding of how gender norms and the expression of emotions may affect the use of counseling services in this population, are needed to facilitate access and the provision of culturally sensitive interventions.

Moreover, results from the included studies showed that religiosity and having adequate social support are valuable coping strategies for coping with bereavement among Latinos. Nonetheless, some things are important to consider. For instance, consistent with prior research, our results showed that Latina widows find greater comfort than their male counterparts in attending religious services (Fahmy, 2018). Potential explanations for the aforementioned gender differences include modern secularization that affect men and women differently so that men have greater exposure to social sources that undermine religion (e.g., science, work outside home); increased “existential insecurity” among women due to lower economic stability and physical safety that leads women to seek safety and well-being in religion; and greater social networks for women attending religious institutions which serve as reinforcements to keep attending services (Fahmy, 2018). Research to support the aforementioned assertions is needed to better understand the role of church attendance in coping with bereavement among Latinos. Also, although the value of religiosity and social support is widely documented in the bereavement literature (Wortmann & Park, 2008), there may be other specific aspects of religiosity and/or types of social support that could further facilitate coping with bereavement among Latinos. Unfortunately, this information is limited. For instance, increasing our understanding of how aspects of religiosity such as God locus of control or beliefs about the afterlife may promote well-being among bereaved Latinos is in need of further study.

Likewise, increasing insight as to the type of social support (e.g., emotional, instrumental, informational, appraisal) that may be more effective for certain bereaved individuals could be highly valuable to inform the development of psychosocial interventions. Indeed, understanding the aforementioned factors and their effects on the bereavement process, as well as identifying the specific mechanisms by which religiosity and social support may promote resilience among widowed Latinos may point to nontraditional sources of service delivery (e.g., faith-based organizations) and culturally-sensitive interventions valuable to ameliorate distress among the bereaved.

In addition to the aforementioned recommendations, findings from this review are helpful to outline additional directions for future research aimed at informing the needs of widowed Latinos. First, future studies should aim to incorporate the use of mixed methodology. The use of combined methods provides an opportunity to better understand and contextualize the bereavement process from multiple perspectives. While quantitative methods provide a measure for the pervasiveness of risk, patterns of association, and the effectiveness of coping strategies to facilitate resilience, qualitative information facilitates understanding as to why and/or how such associations exist and can explain the variations of their effects (Creswell, Klassen, Clark, & Smith, 2011). Also, the use of qualitative information to supplement quantitative data is particularly valuable with this population, given variations across gender, country of origin, immigration status, and acculturation background. The use of mixed methods would also be particularly valuable to study the health effects of complex cultural beliefs about death (e.g., continued bond with the deceased) and related rituals (e.g., Novena) among bereaved Latinos.

Second, adopting a contextually and culturally-sensitive approach to research is essential to further our understanding of the bereavement process among widowed Latinos. This involves the development of studies that incorporate the use of reliable translation methods and cross-culturally validated measures with psychometrically sound properties, along with the assessment of relevant cultural constructs (e.g., Latino values), coping strategies (e.g., folk medicine and beliefs), and health outcomes (e.g., nervios). Third, as emphasized in the included studies, longitudinal designs are particularly preferable for the study of bereavement given the wide variation in risk and symptom presentation that exist over the course of bereavement (Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). If possible, future studies should aim at collecting data at multiple time points, including the first months since spousal death, which has been identified as a high-risk period (Buckley et al., 2010), and at least six months after the death to inform the needs of those with complicated grief (Prigerson et al., 1995). Fourth, given the prevalence of social disadvantage among Latinos and its potential effect on bereavement, additional studies to further identify and understand specific behavioral and biological pathways through which social disadvantage and contextual stress affect the health of bereaved Latinos are needed. Finally, given the relevance of religiosity and social networks to the bereavement process, especially in the Latino population, studies adopting an interdisciplinary approach to research are warranted to strengthen methodology, lead to more accurate interpretation of findings, and better translate research into practice. This includes, for instance, actively collaborating with counselors/psychologists, faith-based leaders, ethnographers, gerontologists, public health specialists, community leaders, and their organizations.

Limitations

This study adds to the bereavement literature by providing a detailed analysis of methodology and findings from peer-review studies and narrative reviews on the topic of bereavement among widowed Latinos in the US, as well as proposing directions for future research. Nevertheless, this review has some limitations, most of which stem from the exclusion criteria used to select eligible studies. Also, the comparison of findings across studies was difficult given differences in measures used and variations in reported measures of association.

Conclusion

The death of a spouse is one of the most stressful events a person may face. The goal of this study was to examine existing research on the unique risk factors, outcomes, and coping strategies commonly used among Latinos facing widowhood in the US. The results highlight that research to inform the health needs of widowed Latinos is limited, and additional studies with enhanced methodological rigor are needed to better understand the complex needs of this vulnerable population. Moreover, this information is needed to inform the development of culturally and contextually-sensitive interventions and prevention efforts, as well as advocacy and policy. Given demographic trends over the next few decades that project a rapid increase in the Latino elderly population who may be likely to face widowhood, it is in our best interest to further the research agenda in this needed area of study by using methodological rigor, an interdisciplinary approach, and culturally and contextually-sensitive practices to inform the needs of widowed Latinos.

Funding

Data collection and preparation of the manuscript was supported by the Ford Foundation Fellowship Program and a grant and diversity supplement from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [1R01HL127260-01].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- Angel JL, Douglas N, & Angel RJ (2003). Gender, widowhood, and long-term care in the older Mexican American population. Journal of Women & Aging, 15(2–3), 89–105. doi: 10.1300/J074v15n02_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel JL, Jimenez MA, & Angel RJ (2007). The economic consequences of widowhood for older minority women. The Gerontologist, 47(2), 224–234. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwell C (1985). An attitudinal correlate of the timing of a major life event: The case of morale in widowhood. Family Relations, 34(4), 577–581. doi: 10.2307/584022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartrop R (2017). Cardiovascular risk following widowhood: Increasing clarity from new research models. Coronary Artery Disease, 28(2), 93–94. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo V (2017). Coping with dying and deaths at home: How undocumented migrants in the United States experience the process of transnational grieving. Mortality, 22(1), 33–44. doi: 10.1080/13576275.2016.1192590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley T, McKinley S, Tofler G, & Bartrop R (2010). Cardiovascular risk in early bereavement: A literature review and proposed mechanisms. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(2), 229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements P, Vigil G, Manno M, Henry G, Wilks J, Das S, … Foster W (2003). Cultural perspecrtives of death, grief, and bereavement. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 41(7), 18–26. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-20030701-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles KV (1996). Cultural perspectives of grief: An expanded concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23(2), 287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb02669.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Clark VLP, & Smith KC for the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, NIH. (2011). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. Retrieved from http://obssr.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research/pdf/Best_Practices_for_Mixed_Methods_Research.pd

- Diaz-Cabello N (2004). The Hispanic way of dying: Three families, three perspectives, three cultures. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 12(3), 239–255. doi: 10.1177/1054137304265757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbruch M (1984a). Cross-cultural aspects of bereavement. I: A conceptual framework for comparative analysis. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 8(3), 283–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00055172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbruch M (1984b). Cross-cultural aspects of bereavement. II: Ethnic and cultural variations in the development of bereavement practices. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 8(4), 315–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00114661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy D (2018). Christian women in the US are more religious than their male counterparts. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2018/04/06/christian-women-in-the-u-s-are-more-religious-than-their-male-counterparts/

- Gallo LC, Bogart LM, Vranceanu A-M, & Matthews KA (2005). Socioeconomic status, resources, psychological experiences, and emotional responses: A test of the reserve capacity model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(2), 386–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Smith TW, & Cox CM (2006). Socioeconomic status, psychosocial processes, and perceived health: An interpersonal perspective. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 31(2), 109–119. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza JR, Glenn BA, Mistry RS, Ponce NA, & Zimmerman FJ (2017). Subjective social status and self-reported health among US-born and immigrant Latinos. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(1), 108–119. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0346-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski JA, & Frantz TT (1993). Latinos and Anglos: Cultural experiences of grief intensity. Omega -Journal of Death and Dying, 26(4), 273–285. doi: 10.2190/7MG3-KXKH-NMV8-BY90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy-Bougere M (2008). Cultural manifestations of grief and bereavement: A clinical perspective. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 15(2), 66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges P, Dunn K, Wagner D, & Royall D (2005). Predictors of quality of life in older Mexican American women. Gerontologist, 45, 346. [Google Scholar]

- Ide BA, Tobias C, Kay M, & de Zapien J (1992). Prebereavement factors related to adjustment among older Anglo and Mexican-American widows. Clinical Gerontologist, 11(3–4), 75–91. doi: 10.1300/J018v11n03_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ide BA, Tobias C, Kay M, Monk J, & de Zapien JG (1990). A comparison of coping strategies used effectively by older Anglo and Mexican-American widows: A longitudinal study. Health Care for Women International, 11(3), 237–249. doi: 10.1080/07399339009515895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay M, Tobias C, Ide B, De Zapien JG, Lee Monk J, Bluestein M, & Fernandez ME (1988). The health and symptom care of widows. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 3(3), 197–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00116677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, & Bradatan C (2006). Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In: National Research Council (US) Panel on Hispanics in the United States. In Tienda M & Mitchell F (Eds.), Hispanics and the future of America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). [Google Scholar]

- Lawson TJ (1990). The role of social support orientation in moderating the stress-buffering effect of social support. ProQuest Information & Learning. Dissertation Abstracts International, 50(12-B), 5927–5927. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, & Carr D (2007). Does the context of spousal loss affect the physical functioning of older widowed persons? A longitudinal analysis. Research on Aging, 29(5), 457–487. doi: 10.1177/0164027507303171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, … Moher D (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod S, Musich S, Hawkins K, Alsgaard K, & Wicker ER (2016). The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), 266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miville ML, Mendez N, & Louie M (2017). Latina/o gender roles: A content analysis of empirical research from 1982 to 2013. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 5(3), 173–194. doi: 10.1037/lat0000072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales LS, Lara M, Kington RS, Valdez RO, & Escarce JJ (2002). Socioeconomic, cultural, and behavioral factors affecting Hispanic health outcomes. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 13(4), 477–503. doi: 10.1177/104920802237532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L (1976). A re-examination of widowhood and morale. Journal of Gerontology, 31(6), 687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Zemore SE, & Greenfield TK (2008). Social disadvantage, stress, and alcohol use among Black, Hispanic, and White Americans: findings from the 2005 US national alcohol survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(6), 824–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munet-Vilaro F (1998). Grieving and death rituals of Latinos. Oncology Nursing Forum, 25(10), 1761–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Hispanic Council on Aging. (2017). Status of Hispanic older adults: Insights from the field-caregivers edition. Washington, DC: National Hispanic Council on Aging. Retrieved from ww.nhcoa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2017-Status-of-Hispanic-Older-Adults-FV.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, … Miller M (1995). Inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1–2), 65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoulte J (2011). Bereavement among African Americans and Latino/a Americans. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 33(1), 11–20. doi: 10.17744/mehc.33.1.r4971657p7176307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobralske MC (2016). Health care seeking among Mexican American men. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(2), 129–138. doi: 10.1177/1043659606286767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl ST, & Schulz R (2014). Changes in routine health behaviors following late-life bereavement: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(4), 736–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, & Stroebe W (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet, 370(9603), 1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (2017). Marital status of the US population in 2017. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/242030/marital-status-of-the-us-population-by-sex/

- Vincent GK, & Velkoff VA (2010). THE NEXT FOUR DECADES: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050 (Current Population Reports, P25–1138). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner RM (1993). Psychological adjustments during the first year of single parenthood: A comparison of Mexican-American and Anglo women. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 19(1–2), 121–142. doi: 10.1300/J087v19n01_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, & Park CL (2008). Religion and spirituality in adjustment following bereavement: An integrative review. Death Studies, 32(8), 703–736. doi: 10.1080/07481180802289507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochim BP, & Woodhead EL (2017). Psychology of aging: A biopsychosocial perspective. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]