Abstract

Mass transfer processes are one of the most important operations in chemical, biochemical, and food industries worldwide. In the processes that are controlled by the gas–liquid mass transfer rate, the volumetric mass transfer coefficient kLa becomes a crucial quantity. The dataset was measured with the aim to create a correlation for kLa prediction in a non-coalescent batch under the wide range of experimental conditions. The dynamic pressure method, which was reported as physically correct in the past, was chosen to be the method for experimental determination of kLa. Our previous work targeted the kLa dependencies in viscous and coalescent batches resulting in correlations that are viable for the broad range of process conditions. We reported that the best-fit correlation is based on the hydrodynamic parameter circumferential velocity of impeller blades in the case of non-coalescent liquids in the vessel equipped by single or multiple impellers at a constant D/T ratio (diameter of the impeller to the inner diameter of the tank). Now, we focus on the influence of various impeller diameters on transport characteristics (mainly kLa) in a non-coalescent batch. The experiments are carried out in a multiple-impeller vessel equipped with Rushton turbines (of four diameters) and in both laboratory and pilot-plant scales. Various impeller frequencies and gas flow rates are used. We examine the suitability of the hydrodynamic description, which was reported in the past, to predict kLa also when the D/T ratio changes. We show that the correlation based on the energy dissipation rate better fits the experimental data and predicts kLa values more accurately in the case of varying D/T values. This correlation could be adopted in the design and scale-up of agitated devices operating with non-coalescent batches.

1. Introduction

The necessity to optimize gas–liquid mass transfer rises many times in chemical, biochemical, and food industries. The mass transfer operations are often carried out in mechanically or pneumatically agitated contactors with the preference of mechanically agitated ones due to their ability to easily vary operational conditions. The mechanically agitated contactors are adopted under a wide range of operational conditions in fermentation, hydrogenation, chlorination, and many other mass transfer processes. To optimize the contactor performance, various impeller types are used to optimize the flow pattern. The most significant limitation to the utilization of mechanically agitated gas–liquid contactors is the uncertainty in their design. The contactors are commonly designed on the basis of empirical correlations, which are assumed to be built on correct experimental data. As will be discussed below, many experimental techniques to obtain kLa reported in the literature for several decades have, unfortunately, proved to produce erroneous data by multiples. Due to the lack of newer kLa data, inaccurate correlations are still used.

Also, the appropriate design through the first-principle-based chemical engineering data cannot be utilized due to the complexity of transport phenomena in mechanically agitated gas–liquid dispersions, as will also be discussed further. Therefore, experimental research of mass transfer characteristics is a crucial task, and physically correct data on the volumetric mass transfer coefficient, kLa, are needed to design the processes where the gas–liquid mass transfer becomes the rate-controlling step.

Because of the well-known fact that no single kLa correlation can describe the data from all batches (see, e.g., Markopoulos et al.1), it was suggested by Zlokarnik2 to split gas–liquid systems into coalescent and non-coalescent ones. This suggestion was made on the basis of different bubble interactions in the observed systems. The differences in bubble interactions significantly affect the kLa values,3 and the transition between coalescent and non-coalescent behavior is sharp.4,5 Even though the differences between coalescent and non-coalescent batches were studied by multiple researchers, the phenomenon has not been fully understood so far, and the heuristic division into these categories remains the most reliable way.

The complexity of hydrodynamic conditions in gas–liquid contactors is a reason why the theoretical prediction is not a common approach. Some CFD simulation studies on this topic have been published and overviewed by Ranganathan.6 The overview led to the conclusion that, to be able to compute the CFD model, significant simplifications had to be made, and therefore, the model was not able to describe the studied system for a sufficiently wide range of process conditions.

For the experimental determination of kLa, various methods (dynamic pressure method, steady-state sulfite method, and others) have been developed in the course of years. After testing,7−9 the dynamic pressure method, DPM, has been established as the best method, which can even measure high kLa values correctly. Unfortunately, most of the literature data for the non-coalescent batch was measured by methods that significantly underestimate the kLa at high absorption rates (kLa > 0.2 s–1) and therefore has no apparent physical meaning.10 The literature offers many correlation shapes for kLa prediction, which are based on experimental data, but, in addition, a significant amount of those was measured only in a specific configuration and has not been verified for various liquids, vessel sizes, and multiple-impeller vessels. In general, the design of industrial-scale equipment according to literature correlations is still uncertain.2,11 In our previous work, we focused on kLa prediction for gas–liquid contactors equipped with Rushton turbines in the viscous batch12,13 and coalescent batch (water).14 In this work, we target the prediction of kLa for the non-coalescent batch, and, in addition, introducing a new parameter studied, various impeller diameters. The effect of impeller diameters will be investigated using Rushton turbines at four various D/T values in single, double, and triple impeller configurations.

The resulting correlation for kLa prediction in non-coalescent gas–liquid contactors will be established on the basis of the extensive experimental dataset, and its reliability will be verified.

2. Theory

The specialized literature offers kLa correlations based on different quantities. One of the standardly used descriptions is based on the theory of isotropic turbulence.15 In this category, the basic correlation shape, frequently used in the literature, has the following form:

| 1 |

The constants C1, C2, and C3 vary from author to author. The correlations published to predict kLa values in the non-coalescent batch mixed by Rushton turbines are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of Correlations for Non-coalescent Batch Mixed by Rushton Turbines.

| correlation shape: kLa | setup | batch | concentration | T | authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.67 × 10–4 (Pg/V)0.98vs0.4 | 1 RT | Na2SO4 | 0.5 M | 0.15 m | Puskeiler et al.16 |

| 6.76 × 10–3 (Pg/V)0.94vs0.65 | 2 RT | Na2SO4 | 0.56 M | 0.21 m | Vilaça et al.17 |

| 2.80 × 10–3 (Pg/V)0.79vs0.349 | 2 RT | Na2SO4 | 0.2 M | 0.3 m | Gezork et al.18 |

| 4.90 × 10–4 (Pg/V)1.22vs0.452 | 3 RT | Na2SO4 | 0.5 M | 0.3 m | Fujasová19 |

| 4.17 × 10–4 (Pg/V)1.17vs0.34 | 3 RT | Na2SO4 | 0.5 M | 0.6 m | Linek10 |

It is worth noting that the values of constant C2 significantly differ in Table 1. The reason for such significant differences among published data are various measurement methods. The kLa was measured using various experimental techniques; many of which produce kLa values distorted by a disagreement between the mathematical model and physical reality in experiments.20 The analysis of particular phenomena in individual experimental techniques showed that, in various experimental techniques, another phenomenon controls the interfacial mass transfer rate rather than the one assumed in the evaluation model. As one example for all, let us mention the mass transfer rate controlled by gas holdup residence time instead of the volumetric mass transfer coefficient as described by Linek.7 Most of the correlations quoted in Table 1 are not reliable for industrial design and scale-up owing to only one size of the experimental apparatus.2

One way to refine kLa predictions was the inclusion of the energy dissipated by gas bubbles expansion in the batch as presented, for example, by Labík et al.21 The total power input, PTOT, could be then calculated using the additional term to the impeller power:

| 2 |

Labík et al.21 created and tested several new dimensional correlations. Some of the correlations involved the impeller tip speed term (ND) or the impeller power number (P0), which stands for specifics in impeller mixing patterns and can be calculated as

| 3 |

The second fairly popular option of how to describe kLa is dimensionless equations. Due to the physical differences in the batch behavior, the split into dimensionless equations for coalescent and non-coalescent batches is kept. This approach is necessary until the coalescent and non-coalescent behavior would be examined and fully understood.2 Moucha et al.20 showed that the impeller tip speed is better for kLa prediction in the non-coalescent batch than the gassed power input when the data obtained by various impellers are correlated. Labík et al.21 provided another set of experimental data that supported this conclusion and presented the suitable correlation for kLa prediction in the non-coalescent batch on the basis of the robust experimental dataset. This conclusion was, however, made using the only single value of the impeller to the tank diameter ratio, D/T = 1/3.

In the frame of this work, we aim to test literature kLa correlations or, alternatively, establish another one to develop the reliable tool for gas–liquid contactor design also in the cases of D/T ratios significantly different from 1/3. For this purpose, we selected both dimensional and dimensionless literature correlations as they are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of Other Dimensional and Dimensionless Correlation Shapes that Were Tested.

3. Results and Discussion

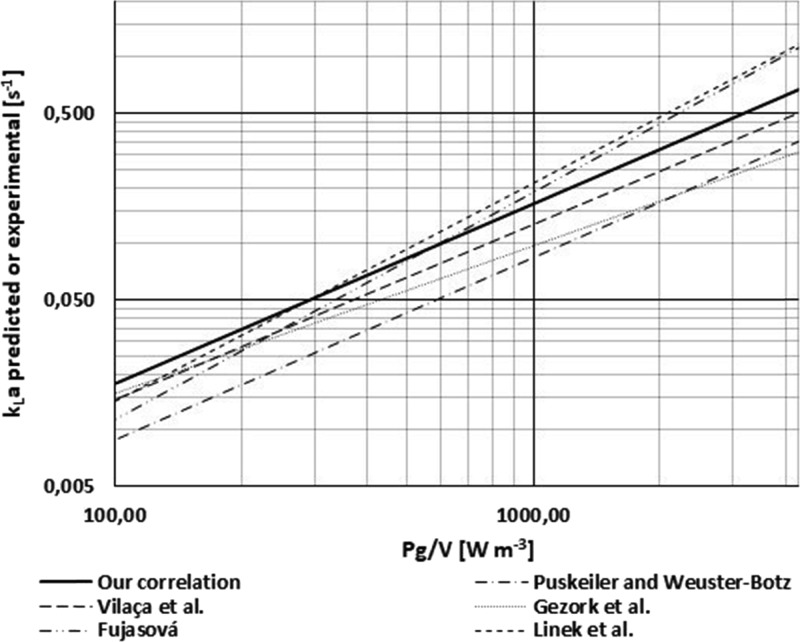

First of all, correlation 1 was fitted to the measured data and compared with literature-based correlations given in Table 1. The results are depicted in Figure 1. The fitted correlation shape has the following form:

Figure 1.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of correlation 4 with literature ones.

Even though our correlation roughly corresponds with the data presented in the literature, Figure 2 shows that its shape (correlation 1) is not suited for kLa prediction for devices of different sizes. Predicted data for the smaller vessel (T29) are significantly underestimated in comparison to the measured data. On the other hand, when T is kept constant, correlation shape 1 is able to predict kLa values regardless of the D/T ratio because the data for the T59 vessel where various D/T values were used are concentrated into one cluster, that is, they are not separated according to D values. The results obtained from fitting parameters to correlation 4 (Figure 3) give almost identical results like the ones presented for correlation 1. It means that the involvement of the energy dissipated by gas bubble expansion is not significant, even though, at low impeller speeds, gas expansion contributes to the total energy dissipated by tens of percent.

Figure 2.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of correlation 4 and measured data for two different vessel sizes and various impeller diameters.

Figure 3.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of correlation 4 and measured data for two different vessel sizes and various impeller diameters.

In the case of correlation shape 4, the predicted data for the T29 vessel are also underestimated in comparison to the measured data. Due to this inconsistency, correlation 5 based on the circumferential velocity of impeller blades reported by Moucha et al.20 and Labík et al.21 was tested; the result of which is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of correlation 4 and measured data for two different vessel sizes and various impeller diameters.

Figure 4 shows that the relative standard deviation, RSD, increased in correlation 5. The predicted data for T29 are again underestimated, and therefore, it could be concluded that correlation 5 is not able to predict kLa in a vessel equipped with impellers of various D/T ratios in a non-coalescent batch.

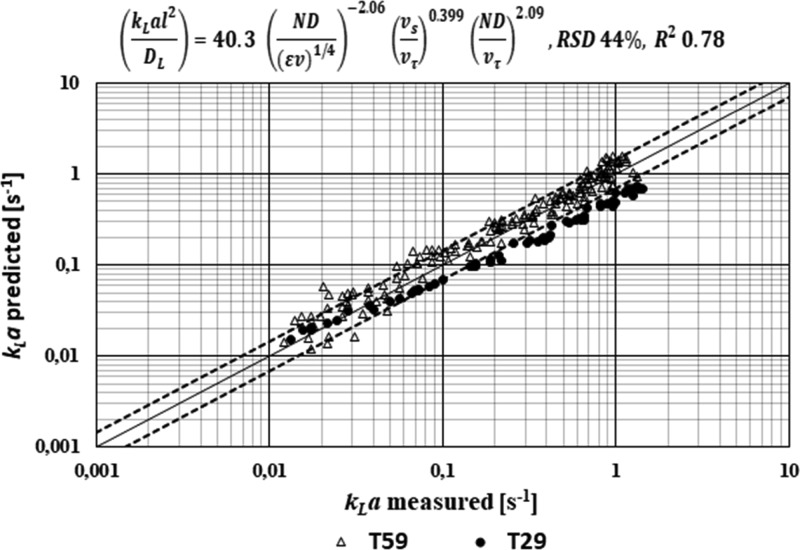

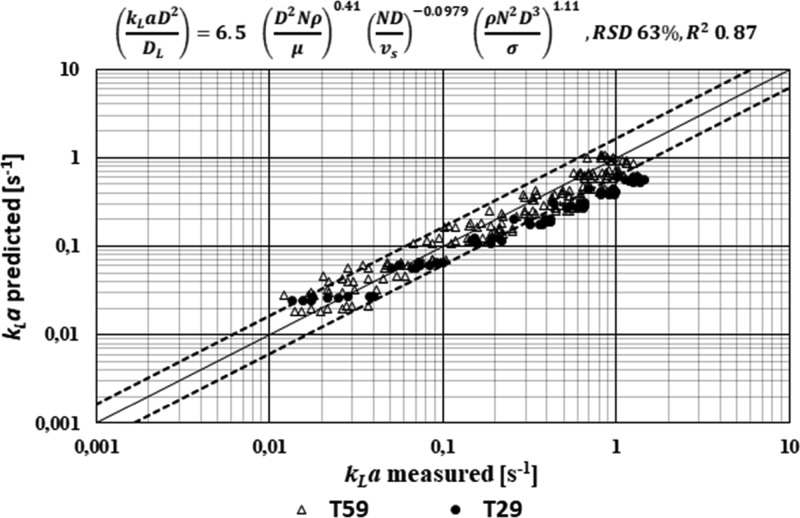

Further, Figures 5–7 show how the dimensionless correlations 6–8, respectively, described our experimental data.

Figure 5.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of dimensionless correlation 6 and measured data for two different vessel sizes and various impeller diameters.

Figure 7.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of dimensionless correlation 8 and measured data for two different vessel sizes and various impeller diameters.

From the comparison of individual correlations’ closeness, we can see a more precise kLa prediction in the dependence on the energy dissipated in the batch (correlation 6 in Figure 5) than the prediction based on the circumferential velocity of impeller blades (correlations 7 and 8 in Figures 6 and 7, respectively). This finding differs from that made by Moucha et al.20 and Labík et al.21 It is necessary to stress that the findings by Moucha et al.20 and Labík et al.21 resulted from the data measured only for D/T = 1/3. In their case, more uniform circulation loop velocities were achieved, which corresponded with similar gas holdup values and through the interfacial area values and also with similar kLa values. Here, when the impeller diameter varies, significantly different fractions of bubbles are engaged into recirculation loops at similar dissipation intensities, and the kLa prediction based on ND is not the optimal one.

Figure 6.

Comparison of predicted kLa data on the basis of dimensionless correlation 7 and measured data for two different vessel sizes and various impeller diameters.

Further statistical data related to correlation 6 are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Statistical Data Describing Correlation 6 Coefficients.

| constant | value | p value | lower 95% confidence limit | upper 95% confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.0187 | 2.61 × 10–12 | 0.0107 | 0.0330 |

| C2 | 1.05 | 1.40 × 10–189 | 1.02 | 1.08 |

| C3 | 0.506 | 5.69 × 10–52 | 0.453 | 0.558 |

Even though correlation 6 provides the best results in terms of RSD, the data from smaller scales seem to differ systematically. To check the correctness of the correlation, we decide to fit the data from laboratory and pilot plant scales separately. Obtained results were used for t-tests of separated datasets with the confidence limit set to 95%. The value of calculated t = 1.645 is lower than tcritical,0.975 = 1.96 and therefore not statistically significant with 95% confidence. We can correlate both datasets altogether.

4. Conclusions

In the frame of long-term research of transport characteristics in mechanically agitated dispersions, the new aspect was described for non-coalescent batches, the variation in the D/T ratio. The new aspect also brought the new conclusion about the best correlation shape to predict kLa data for scaling up purposes. In the case of different D/T values, the kLa prediction based on the circumferential velocity of impeller blades did not prove to be better, as it was previously reported in the case of a constant D/T. Even if similar ND values are set using the impellers of different diameters, the recirculation loops’ length is different, and the liquid flowing out of the impeller spills into a larger cross-sectional area, reducing the recirculation loop’s velocity. Also, the energy dissipation intensity varies significantly, when the same ND value is set using various D/T values. This work leads us to the conclusion that, in the cases where the D/T values varied in non-coalescent batches, the best employable correlation in the fermenter design proved to be the dimensionless one suggested by Zlokarnik.23

|

9 |

which can be explained as follows. Using different impeller diameters, at a single energy dissipation intensity, we reach different velocities in the impeller recirculation loops, which means different magnitudes of the drag force engaging gas bubbles into the recirculation. The equilibrium between the drag forces and buoyancy forces determines the amount of bubbles engaged. This affects kLa values and is described by the ratio of energy dissipation intensity Pg/V and drag forces against buoyancy vg, which is used in Zlokarnik’s correlation. Further reason for better prediction using Zlokarnik’s correlation can lie in the fact that Q/V better corresponds with the mean gas residence time, that is, also with the gas holdup, which is similar in the vessels of different scales at the same Q/V. Nevertheless, varying recirculation-loop velocity also slightly changes mass transfer intensities, which is seen in slightly different trends in the data of various diameters. Even under these circumstances, we recommend the usage of correlation 6 because of the acceptably low relative deviation from the viewpoint of industrial design.

5. Materials and Methods

The experimental setup and measurement techniques were already described in depth in our previous work.25,26 The experiments were performed in two different vessel sizes: the laboratory-scale one with the inner diameter of the vessel, T, equal to 0.29 m and the pilot plant-scale one with T equal to 0.59 m. Each of the vessels contained four baffles with a thickness equal to T/10 that means 0.029 m in the case of a laboratory vessel and 0.059 m in the case of a pilot plant scale vessel. Single, double, or triple impellers were gradually used. The impeller diameter, D, used in the laboratory scale vessel was 0.1 m, which corresponds to the D/T ratio equal to 0.33. In the pilot plant, the four different diameters of impellers were used. The sizes of employed impellers were 0.15 m (D/T = 0.25), 0.2 m (D/T = 0.33), 0.24 m (D/T = 0.4), and 0.27 m (D/T = 0.46). The inter-impeller clearance was always equal to T; therefore, each impeller region (section) height was equal to the tank diameter. The liquid volume was 18.3 L in each section of the laboratory vessel and 153 L in each section of the pilot-plant vessel. The schemes of both apparatuses are depicted in our previous publications.25,26 The major difference between the apparatuses of both sizes lies in the dish-shaped pilot-plant bottom in contradiction to the flat-shaped laboratory bottom.

The dynamic pressure method, DPM, was employed to measure kLa. The pressure change in the vessel was approximately 15 kPa. The pressure time profile as well as that of the oxygen concentration was monitored and recorded.

The evaluated kLa is calculated as the average value of individual kLa values measured in each impeller region. The average kLa is more accurate and able to better describe mass transfer in the vessel as a whole. The same approach to experimental data treatment was adopted and recommended by Fujasová.19 The accuracy of the established correlations for further data prediction was quantified by relative standard deviation, RSD, between experimental values of kLa and the predicted ones.

The batch temperature was set to 20 ± 0.1 °C. Superficial gas velocities during measurements in both vessels were set at 0.00212, 0.00424, and 0.00848 m s–1, respectively. Impeller mixing frequencies differed from 250 to 850 rpm in the laboratory scale and from 100 to 1000 rpm in the pilot plant-scale vessel.

The experimental batch was a 0.5 M aqueous solution of Na2SO4 that exhibits non-coalescent behavior. The physical properties of the batch that were used for evaluation are listed in Table 4. The diffusivity was measured by the polarographic oxygen probe according to the method described by Elgozali.27 For the viscosity measurement, a rotational rheometer was employed, and finally, for measurements of surface tension, the Du Noüy ring method was applied.

Table 4. Physical Properties of the Used Batch (0.5 M Solution of Na2SO4) at 20 °C.

| physical quantity | value |

|---|---|

| ρ [kg m–3] | 1054 |

| μ [mPa s] | 1.22 |

| σ [mN m–1] | 74.1 |

| DO2 [10–9 m2 s–1] | 1.87 |

| DN2 [10–9 m2 s–1] | 1.66 |

A six-blade Rushton turbine was chosen as an impeller for all the measurements. The Rushton turbine is an impeller with a radial flow pattern and is utilized in many industrial processes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from Specific University Research (MSMT no. 21-SVV/2018) and the European regional development fund project ORGBAT no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_025/0007445 are gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Symbols Used

- a

[m2 m–3] gas–liquid interfacial area per unit liquid volume

- Ci

[−] empirical constants in the correlations of transport characteristics

- D

[m] impeller diameter

- DL

[m2 s–1] diffusivity of gas in solution

- g

[m s–2] gravitational constant

- kL

[m s–1] mass transfer coefficient

- kLa

[s–1] volumetric mass transfer coefficient

- l

[m] characteristic scale defined as Batchelor’s microscale of turbulence

- N

[s–1] impeller frequency

- PTOT

[W m–3] total power input with gas expansion

- Pg

[W] specific power dissipated by impeller under gassed condition

- Pu

[W] specific power dissipated by impeller under ungassed condition

- P0

[−] impeller power number

- Q

[m3 s–1] gas flow rate

- T

[m] vessel diameter

- V

[m3] liquid volume

- vs

[m s–1] gas superficial velocity

- vt

[m s–1] bubble terminal velocity

Greek letters

- ε

[W kg–1] energy dissipation intensity (= P/ρ)

- μ

[Pa s] dynamic viscosity of liquid

- ν

[m2 s–1] kinematic viscosity of liquid

- ρ

[kg m–3] density

- σ

[kg s–2] surface tension

Abbreviations

- CFD

computational fluid dynamics

- DO

dissolving oxygen

- DPM

dynamic pressure method

- RT

Rushton turbine

- RSD

relative standard deviation

- T29

laboratory scale vessel

- T59

pilot-plant scale vessel

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Markopoulos J.; Christofi C.; Katsinaris I. Mass Transfer Coefficients in Mechanically Agitated Gas-Liquid Contactors. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2007, 30, 829–834. 10.1002/ceat.200600394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokarnik M.Scale-up in Chemical Engineering; 2 ed.; Wiley: Weinheim, 2006, 10.1002/352760815X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K.; Nienow A. W. Bubble sizes and coalescence rates in an aerated vessel agitated by a Rushton turbine. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1993, 26, 536–542. 10.1252/jcej.26.536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradnik J.; Fialová M.; Linek V. The effect of surface-active additives on bubble coalescence in aqueous media. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1999, 54, 4757–4766. 10.1016/S0009-2509(99)00192-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo L. A.; Ohnishi S.; Horn R. G. Inhibition of bubble coalescence: Effects of salt concentration and speed of approach. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 356, 316–324. 10.1016/j.jcis.2010.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan P.; Sivaraman S. Investigations on hydrodynamics and mass transfer in gas-liquid stirred reactor using computational fluid dynamics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 3108–3124. 10.1016/j.ces.2011.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linek V.; Sinkule J.; Beneš P. Critical assessment of gassing-In methods for measuringklain fermentors. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1991, 38, 323–330. 10.1002/bit.260380402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linek V.; Sinkule J.; Benes P. Critical assessment of the dynamic double-response method for measuring kLa experimental elimination of dispersion effects. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1992, 47, 3885–3894. 10.1016/0009-2509(92)85137-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linek V.; Beneš P.; Sinkule J. Critical-assessment of the steady-state Na2SO3 feeding method for kLa measurement in fermentors. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1990, 35, 766–770. 10.1002/bit.260350803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linek V.; Moucha T.; Rejl F. J.; Kordač M.; Hovorka F.; Opletal M.; Haidl J. Power and mass transfer correlations for design of multi-impeller gas-liquid contactors for non-coalescent electrolyte solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 209, 263–272. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seichter P. Power input of aerated agitator system of high-speed fermenter. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1987, 52, 2181–2187. 10.1135/cccc19872181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petříček R.; Moucha T.; Jońaš Rejl F. J.; Valenz L.; Haidl J. Volumetric mass transfer coefficient in the fermenter agitated by Rushton turbines of various diameters in viscous batch. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2017, 115, 856–866. 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.07.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petříček R.; Moucha T.; Rejl J. F.; Valenz L.; Haidl J.; Čmelíková T. Volumetric mass transfer coefficient, Power input and Gas hold-up in viscous liquid in mechanically agitated fermenters. Measurements and scale-up. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2018, 124, 1117–1135. 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petříček R.; Moucha T.; Kracík T.; Rejl F. J.; Valenz L.; Haidl J. Volumetric mass transfer coefficient in the fermenter agitated by Rushton turbines of various diameters in coalescent batch. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2019, 130, 968–977. 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.10.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. M.; Fernstrom G. A.; Miller S. A. Correction - Performance of Agitated Gas-Liquid Contactors. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 1944, 36, 857–857. 10.1021/ie50417a601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puskeiler R.; Weuster-Botz D. Combined sulfite method for the measurement of the oxygen transfer coefficient kLa in bioreactors. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 120, 430–438. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaça P. R.; Badino A. C. Jr.; Facciotti M. C. R.; Schmidell W. Determination of power consumption and volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient in bioreactors. Bioprocess Eng. 2000, 22, 0261–0265. 10.1007/s004490050730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gezork K. M.; Bujalski W.; Cooke M.; Nienow A. W. Mass Transfer and Hold-up Characteristics in a Gassed, Stirred Vessel at Intensified Operating Conditions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2001, 79, 965–972. 10.1205/02638760152721514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujasová M.; Linek V.; Moucha T. Mass transfer correlations for multiple-impeller gas-liquid contactors. Analysis of the effect of axial dispersion in gas and liquid phases on ″local″ k(L)a values measured by the dynamic pressure method in individual stages of the vessel. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62, 1650–1669. 10.1016/j.ces.2006.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moucha T.; Rejl F. J.; Kordač M.; Labík L. Mass transfer characteristics of multiple-impeller fermenters for their design and scale-up. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 69, 17–27. 10.1016/j.bej.2012.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labík L.; Moucha T.; Kordač M.; Rejl F. J.; Valenz L. Gas-Liquid Mass Transfer Rates and Impeller Power Consumptions for Industrial Vessel Design. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2015, 38, 1646–1653. 10.1002/ceat.201500209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labík L.Study of gas-liquid mass transfer in a mechanically agitated fermentor . Department of chemical engineering. University of chemistry and technology, Prague., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zlokarnik M. Sorption characteristics for gas-liquid contacting in mixing vessels. Biotechnol. 1978, 8, 133–151. 10.1007/3-540-08557-2_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ochoa F.; Castro E. G.; Santos V. E. Oxygen transfer and uptake rates during xanthan gum production. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2000, 27, 680–690. 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moucha T.; Linek V.; Erokhin K.; Rejl J. F.; Fujasová M. Improved power and mass transfer correlations for design and scale-up of multi-impeller gas–liquid contactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 598–604. 10.1016/j.ces.2008.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linek V.; Moucha T.; Dousova M.; Sinkule J. Measurement of k(L)a by dynamic pressure method in pilot-plant fermentor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1994, 43, 477–482. 10.1002/bit.260430607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgozali A., Ph.D. Thesis - Hydraulic Mass Transfer Characteristics of gas-liquid contactors with ejector distributor. University of hChemical Technology: Prague: 2001; p 86. [Google Scholar]