Highlights

-

•

icobrain dm is an automated brain MRI segmentation faster than Freesurfer.

-

•

Significantly higher accuracy was obtained for several brain structures, including hippocampus.

-

•

icobrain dm volumes had a test-retest error below normal annual atrophy rates.

-

•

icobrain dm temporal lobe volume had highest sensitivity in discriminating Alzheimer's.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Brain segmentation software, Dementia, Alzheimer's disease (AD)

Abstract

Brain volumes computed from magnetic resonance images have potential for assisting with the diagnosis of individual dementia patients, provided that they have low measurement error and high reliability. In this paper we describe and validate icobrain dm, an automatic tool that segments brain structures that are relevant for differential diagnosis of dementia, such as the hippocampi and cerebral lobes. Experiments were conducted in comparison to the widely used FreeSurfer software. The hippocampus segmentations were compared against manual segmentations, with significantly higher Dice coefficients obtained with icobrain dm (25–75th quantiles: 0.86–0.88) than with FreeSurfer (25–75th quantiles: 0.80–0.83). Other brain structures were also compared against manual delineations, with icobrain dm showing lower volumetric errors overall. Test-retest experiments show that the precision of all measurements is higher for icobrain dm than for FreeSurfer except for the parietal cortex volume. Finally, when comparing volumes obtained from Alzheimer's disease patients against age-matched healthy controls, all measures achieved high diagnostic performance levels when discriminating patients from cognitively healthy controls, with the temporal cortex volume measured by icobrain dm reaching the highest diagnostic performance level (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.99) in this dataset.

1. Introduction

Structural neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (or computed tomography (CT)) plays a key role in the diagnostic work-up of dementia. It allows to rule out structural lesions of the brain that might cause cognitive problems. In addition, structural neuroimaging may contribute to the early and differential diagnosis of the neurodegenerative disease underlying the dementia syndrome (Chui et al., 1992; Roman et al., 1993; Chan et al., 2001; Rosen et al., 2002a, 2002b; Boccardi et al., 2003). Indeed, neurodegenerative disorders that cause dementia are often associated with typical brain atrophy patterns. Alzheimer's disease (AD), for instance, is characterized by medial temporal lobe atrophy, including the hippocampus, and parietal atrophy. Frontotemporal dementia, on the other hand, mainly presents with atrophy of the frontal and (anterior and / or lateral parts of the) temporal lobes. Dementia with Lewy bodies usually does not show specific structural abnormalities, while vascular dementia is mainly characterized by global atrophy and diffuse white matter lesions, lacunes and/or strategic infarcts. As such, global and focal atrophy together with vascular disease are important factors to consider when establishing a differential dementia diagnosis. Gradually, these factors are being included into diagnostic clinical criteria for dementia (McKhann et al., 1984; Roman et al., 1993; Neary et al., 1998; McKhann et al., 2011; McKeith et al., 2017).

Besides contributing to differential diagnosis of prevalent dementia, structural neuroimaging may also aid in predicting progression to dementia in subjects who have not reached the dementia stage yet. MRI studies have shown hippocampal atrophy to be associated with increased risk of progression to dementia due to AD (Dubois, 2018). Hippocampal atrophy is included as a biomarker for early AD diagnosis in the revised diagnostic criteria of the National Institute on Aging – Alzheimer Association working group (Albert et al., 2011; Sperling et al., 2011).

In order to segment brain regions-of-interest and measure brain atrophy, fully automated processing techniques have been developed. These can be used in large study cohorts, saving both time and costs, and are easily reproducible, as opposed to manual segmentation by neuroanatomical experts or semi-automated measures that still require a priori information on the region-of-interest (Duchesne et al., 2002; Barnes et al., 2008; Kennedy et al., 2009; Dewey et al., 2010; Boccardi et al., 2011; Doring et al., 2011; Bosco et al., 2017). FreeSurfer is a very frequently used automatic tool (Fischl, 2012); depending on hardware, may require a long computation time of up to several tens of hours per scan (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/).

Applying automated measures of brain volumes on individual dementia patients requires a low measurement error and high reliability. For instance, a meta-analysis pointed to an annual atrophy rate of the hippocampus of 4.66% in AD patients compared with 1.41% in controls (Barnes et al., 2009). Hence, the measurement error of the brain volumetric measures should be minimal, in order to draw meaningful conclusions in individual patients.

In this study we validate an automated method to measure volumes of the whole brain (WB), total gray matter (GM), frontal, parietal and temporal cortex, hippocampi, and lateral ventricles. In order to evaluate the applicability of the method for brain volume quantification of individual dementia patients, this paper focuses on the accuracy, reliability and diagnostic performance of these volumetric measures.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Dataset 1.a (accuracy)

Dataset 1.a was acquired from 35 healthy subjects (mean age 34 (±20 SD) years, 67% females,) as part of the OASIS project (http://www.oasis-brains.org). Manual brain segmentations were produced by Neuromorphometrics, Inc. (neuromorphometrics.com) using the brainCOLOR labeling protocol. The data were part of the 2012 MICCAI Multi-Atlas Labeling Challenge, where 15 subjects were used as training and the remaining 20 images were used for testing. Since all 35 manual segmentations were made available, we do not make this distinction and, thus, we report results on all 35 images. The 3D magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) T1-weighted MRIs were acquired using a 1.5T Siemens Vision MR scanner, voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm and dimensions up to 256 × 334 × 256 mm.

2.2. Dataset 1.b (accuracy)

Dataset 1.b was acquired from 46 subjects of a memory clinic-based research population who participated in a study at the University of Antwerp, Belgium (mean age 72.0 (±7.8 SD) years, 50.0% females, Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) score 25.8 ± 3.1). This population consisted of 6 cognitively healthy controls as well as patients with subjective cognitive decline (n = 3), mild cognitive impairment (n = 28) and dementia due to AD (n = 9). Local ethics committees (Hospital Network Antwerp and University of Antwerp / Antwerp University Hospital) approved the study and all patients signed informed consent forms. MR imaging was performed on each subject on a 3T whole body scanner with a 32-channel head coil (Siemens Trio/PrismaFit, Erlangen, Germany). The 3D MP-RAGE (TR/TE = 2200/2.45 ms) was used to obtain 176 axial slices without slice gap and 1.0 mm nominal isotropic resolution (FOV = 192 × 256 mm).

An expert (LC) performed bilateral manual hippocampus segmentation on all subjects according to the EADC-ADNI harmonized hippocampus segmentation guidelines (Boccardi et al., 2015). These manual segmentations were further used as ground truth references.

2.3. Dataset 2 (reproducibility)

Dataset 2 consisted of 42 cognitively healthy subjects (i.e., having score 0 on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale) who received longitudinal scans up to 10 days apart (mean age 61.4 (±8.6 SD) years, 59.5% females), provided by the publicly available database OASIS-3 (http://www.oasis-brains.org). MR imaging was performed on each subject on a 3T whole body scanner with a 16-channel head coil (Siemens TIM Trio or BioGraph mMR PET-MR, Erlangen, Germany). The baseline and follow-up scans of three subjects were done on the same scanner, while all other 39 subjects had different scanner types for their baseline and follow-up scans.

The MP-RAGE protocol of TIM Trio scanner was as follows: TR/TE = 2400/3.16 ms, ±176 axial slices without slice gap and 1.0 mm nominal isotropic resolution (FOV = 256 × 256 mm). The MP-RAGE protocol of BioGraph mMR PET-MR scanner was as follows: TR/TE = 2300/2.95 ms, ±176 axial slices without slice gap and 1.2 mm nominal isotropic resolution (FOV = 256 × 256 mm).

2.4. Dataset 3 (diagnostic performance)

Dataset 3 consisted of 46 AD patients (age 71.5 ± 7.2, 60.9% females, Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) 19.2 ± 4) and 23 cognitively healthy subjects (age 70.4 ± 7.1, 47.8% females, MMSE 29.4 ± 0.8) of the publicly available MIRIAD database (miriad.drc.ion.ucl.ac.uk). An overview of the MIRIAD demographics, diagnostic procedures, and imaging protocol was published previously (Malone et al., 2013). In brief, AD patients were diagnosed with mild–moderate probable AD according to the NINCDS–ADRDA clinical criteria (McKhann et al., 1984), while the control subjects did not have subjective cognitive complaints, nor evidence of cognitive impairment. All scans were conducted on a 1.5T whole body scanner (GE Medical systems Signa, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). Three-dimensional T1-weighted (T1w) images were acquired with an IR-FSPGR (inversion recovery prepared fast spoiled gradient recalled) sequence, FOV 240 mm, 256 × 256 matrix, 124 1.5 mm coronal partitions, TR/TE = 15/5.4 ms.

A summary of the 3 datasets can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Short overview of datasets used for method validation.

| DATA | # subjects | Age | Cognitive state | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1.a: accuracy | 35 | 34 ± 20 | Healthy controls | MICCAI 2012 challenge neuromorphometrics.com |

| Dataset 1.b: accuracy | 46 | 72.0 ± 7.8 | MMSE: 25.8 ± 3.1 | University of Antwerp, Belgium |

| Dataset 2: reproducibility | 42 | 61.4 ± 8.6 | Healthy controls | OASIS-3 www.oasis-brains.org |

| Dataset 3: diagnostic performance | 46 | 71.5 ± 7.2 | MMSE: 19.2 ± 4 | MIRIAD miriad.drc.ion.ucl.ac.uk |

| 23 | 70.4 ± 7.1 | Healthy controls |

2.5. MRI analysis

2.5.1. icobrain dm

icobrain dm (version 4.3) is a medical device software that measures relevant volumes of brain structures to assist radiologic assessment of dementia patients. The general icobrain pipeline segments a T1w image into white matter, gray matter and cerebrospinal fluid. When a FLAIR image is available, white matter FLAIR hyper-intensities are also identified and included in the white matter segmentation. The main blocks of the icobrain pipeline have been described previously (Jain et al., 2015); in short, after skull stripping and bias correction, the T1w image is segmented using a probabilistic image intensity model and non-rigidly propagated tissue priors from an MNI atlas (Evans et al., 1992). Lesion segmentation is obtained as intensity outliers to a probabilistic FLAIR image segmentation, and the tissue segmentation is improved iteratively by re-segmenting the lesion-filled T1w image. Volumes are normalized for head size, using the determinant of the affine transformation to MNI atlas as a scaling factor. icobrain dmfurther refines this main tissue segmentation in order to obtain sub-segmentations of cortical gray matter lobes and of the hippocampi.

Sub-segmentations of cortical lobes are obtained from the icobrain cortical gray matter segmentation, annotated according to a set of cortical labels available in MNI space (Klein and Tourville, 2012). Initial non-rigid registration (Modat et al., 2010) between the patient's T1w image and the MNI template is used to obtain a first propagation of the cortical labels from atlas space (“CGM labels”) to the patient's T1w image space. This label propagation is further refined through a second non-rigid registration between the skeleton of the patient's binarized cortical gray matter segmentation and the skeleton of the binarized propagated CGM labels. Finally, each cortical gray matter voxel ias assigned as the cortical label matching the closest voxel in the skeleton of the non-rigidly propagated CGM labels.

Segmentation of the hippocampi starts from the T1w scans preprocessed by the icobrain pipeline, including bias field correction, brain orientation and skull stripping. After preprocessing, a multi-atlas segmentation approach registers binary anatomical priors (i.e., a set of manually annotated hippocampi corresponding to the guidelines of the EADC-ADNI harmonized protocol - (Boccardi et al., 2015)) for left and right hippocampi to the T1w image space using an affine and a non-rigid image registration algorithm. The propagated segmentations are then combined into one probabilistic segmentation for each hippocampus. This label fusion is based on a local ranking using the locally normalized cross correlation as a similarity metric (Cardoso et al., 2013). Subsequently, the probabilistic segmentation of each hippocampus is used as a prior in an intensity-based 2-step maximum likelihood expectation-maximization algorithm (Cardoso, 2012) to obtain the final hippocampus segmentation. As a post-processing step, voxels mainly considered as CSF by the main tissue segmentation are excluded from the hippocampus segmentation, to keep in line with the EADC-ADNI harmonized protocol, which agreed on excluding internal CSF pools from manual hippocampus segmentation. icobrain dm was executed on a Linux server with 8 CPU cores (Intel Xeon Platinum 8000) and 16 GB RAM, and required between 15 and 30 min per scan to complete.

2.5.2. FreeSurfer

The Freesurfer image analysis suite (version 6.0) is documented and freely available for download online (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) and has been thoroughly described elsewhere (Fischl et al., 2002; Fischl, 2012). In this paper, we used the recon-all stream with fully-automated directive -all, in order to reconstruct all brain volumes, including cortical and subcortical parcellations. Since we used very diverse datasets, they were all processed with identical command and default parameters, without optimizing for a specific dataset (e.g., without −3T or -mprage options).

Cortical labels corresponding to the frontal, temporal and parietal gray matter regions were grouped in order to obtain volumes of the same three cortical lobe regions as for icobrain dm.

When reporting volumes normalized for head size, in order to obtain brain volumes in the same range as icobrain, we performed a scaling of the FreeSurfer volumes using the formula below, where 1985.026 ml is the intracranial volume of the MNI template used in icobrain and ‘Estimated Total Intracranial Volume’ is the total intracranial volume reported by FreeSurfer:

FreeSurfer's more recent functionality for segmentation of hippocampal subfields and nuclei of the amygdala (Iglesias et al., 2015) was also applied on the accuracy datasets 1.a and 1.b, from which volumes of the whole left and right hippocampi were extracted.

FreeSurfer was executed on a Linux server with 16 CPU cores (Intel Xeon Platinum 8000) and 64GB RAM, and required between 9 and 13 h per scan to complete.

Both icobrain and FreeSurfer used only the T1w images as input.

2.6. Validation

icobrain dm and FreeSurfer were validated in terms of accuracy, reproducibility and diagnostic performance of all measures. Accuracy of the hippocampal segmentation received special attention, as it was compared against two different approaches implemented in FreeSurfer. Statistical analyses were performed using the integrated development environment for R programming language, RStudio (version 1.0.136) (Team R, 2016). Per experiment, significant differences between icobrain dm and FreeSurfer were evaluated using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test, using R package ‘MASS’ (Venables and Ripley, 2002), at significance level 0.01.

First, we quantified measurement error of all structures and in particular of the hippocampus segmentation with respect to manual ground truth segmentation (datasets 1.a and 1.b). The measurement error was computed as the (absolute) volume difference between ground truth volume and icobrain dm or FreeSurfer volume. In addition, accuracy of the hippocampal segmentation was assessed by the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC). DSC was used to measure the similarity between the ground truth and the automatic segmentation results separately for left and right hippocampus and for total hippocampal volume for each method. According to (Dill et al., 2015) a DSC of 0.80 can be considered a good accuracy value, since it was measured by previous studies as the average rate of similarity between two manual hippocampus segmentations performed by experienced operators.

Subsequently, we assessed reproducibility of all measures on test–retest images from cognitively healthy subjects (dataset 2), based on the absolute volume difference between these pairs of images.

Finally, the diagnostic performance of the measures to distinguish AD patients and cognitively healthy subjects was evaluated (dataset 3) by means of a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis with DeLong tests at significance level 0.05, using the ‘pROC’ package (Robin et al., 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy of brain (sub)structures segmentation

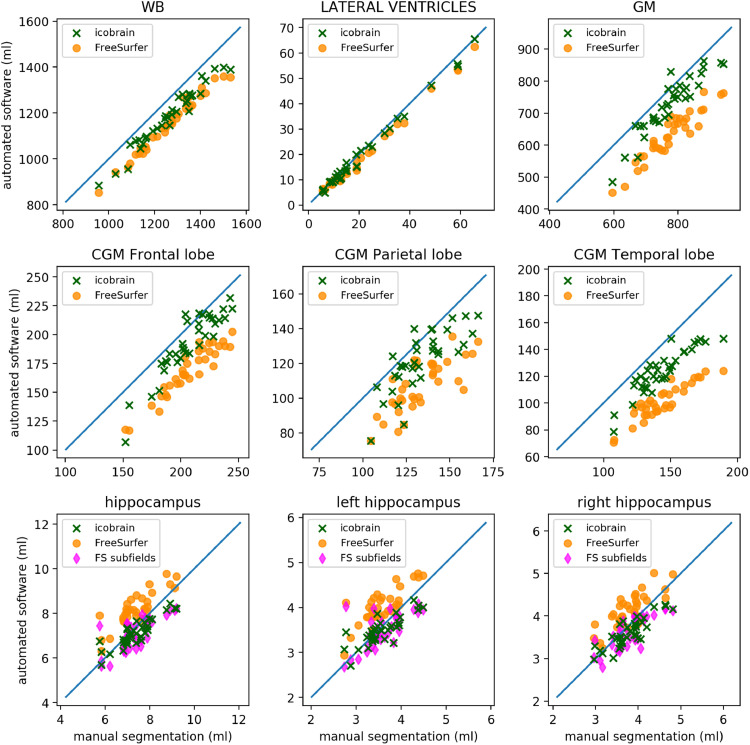

Fig. 1 illustrates the accuracy results for the brain segmentation obtained by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer on dataset 1.a (MICCAI 2012 challenge). These results are also summarized in Table 2. It is obvious that several volumes are biased with respect to the ground truth volumes obtained from manual segmentation, and icobrain dm and FreeSurfer typically have the same bias direction (i.e. underestimation for WB, GM and the cortical lobes), with the exception of the hippocampi, where FreeSurfer's default hippocampus segmentation overestimates most of the volumes. On the other hand, FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality underestimates them. For all measurements, icobrain dm has lower bias and lower absolute error. Moreover, there are fewer outliers.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plots illustrating the brain volumes segmentations by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer (including FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality, denoted “FS subfields”) compared to expert manual segmentation on dataset 1.a.

Table 2.

Accuracy of volumes obtained by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer when compared with expert manual segmentation on dataset 1.a (MICCAI 2012 challenge), where volume differences are computed as ground truth segmentation volume minus volume computed automatically by icobrain dm, FreeSurfer or FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality, “FS subfields”.

| volume differences to ground truth |

absolute volume differences to ground truth |

number of volumetric outliers |

P values icobrain dm vs. FreeSurfer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| icobrain dm | FreeSurfer | icobrain dm | FreeSurfer | icobrain dm | FreeSurfer | ||

| Whole brain | 78.6 | 116.0 | 78.6 | 116.0 | 2 | 6 | < 0.001 |

| (65.5; 91.3) | (97.4; 127.4) | (65.5; 91.3) | (97.4; 127.4) | ||||

| Gray matter | 45.1 | 149.6 | 45.5 | 149.6 | 1 | 21 | < 0.001 |

| (31.1; 71.4) | (123.7; 170.4) | (31.8; 71.4) | (124; 170.4) | ||||

| Frontal lobe | 14.0 | 38.7 | 14.1 | 38.7 | 2 | 13 | < 0.001 |

| (9.4; 20.8) | (34.1; 44.7) | (9.6; 20.8) | (34.1; 44.7) | ||||

| Parietal lobe | 10.0 | 27.2 | 10.6 | 27.2 | 1 | 3 | < 0.001 |

| (4.5; 17.6) | (18.8; 33.8) | (5.3; 17.6) | (18.8; 33.8) | ||||

| Temporal lobe | 21.7 | 42.9 | 21.7 | 42.9 | 1 | 22 | < 0.001 |

| (14.7; 24.3) | (35.8; 48.5) | (14.7; 24.3) | (35.8; 48.5) | ||||

| Hippocampus | 0.3 | −0.7 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1 | 23 | < 0.001 |

| (0.1; 0.6) | (−1.0; −0.2) | (0.2; 0.6) | (0.5; 1.4) | ||||

| Left hippocampus | 0.1 | −0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | 0.01 |

| (−0.1; 0.2) | (−0.5; −0.2) | (0.1; 0.3) | (0.2; 0.7) | ||||

| Right hippocampus | 0.2 | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 13 | 0.02 |

| (0.0; 0.3) | (−0.6; −0.1) | (0.1; 0.3) | (0.3; 0.6) | ||||

| Lateral ventricles | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0 | 4 | 0.006 |

| (−0.3; 1.7) | (0.6; 3.1) | (0.5; 1.7) | (0.8; 3.3) | ||||

| icobrain dm | FS subfields | icobrain dm | FS subfields | icobrain dm | FS subfields | P values icobrain dm vs. FS subfields | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.03 |

| (0.1; 0.6) | (0.0; 0.7) | (0.2; 0.6) | (0.2; 0.7) | ||||

| Left hippocampus | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 2 | 0.23 |

| (−0.1; 0.2) | (0.0; 0.3) | (0.1; 0.3) | (0.1; 0.3) | ||||

| Right hippocampus | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 2 | 0.21 |

| (0.0; 0.3) | (0.0; 0.4) | (0.1; 0.3) | (0.1; 0.4) |

Note: Values in the first 4 columns are median (25–75th quantiles) volume differences or absolute volume difference in ml (not normalised for head size). Volumetric outliers are defined as measurements below (25th percentile - 1.5 interquartile range) or above (75th percentile + 1.5 interquartile range), where these limits are obtained from the volumetric errors of icobrain dm (first column of the table). P values are obtained from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests applied on absolute volume differences for icobrain dm and Freesurfer.

3.2. Accuracy of hippocampus segmentation

Continuing with the dataset 1.a, we report the DSC for hippocampus segmentations for icobrain dm at 0.8223 (0.8142; 0.8321) (median and interquartile range), while FreeSurfer's default hippocampus segmentation scores a DSC of 0.7988 (0.7867; 0.8158). FreeSurfer's newer hippocampal subfield functionality (Iglesias et al., 2015) scores a slightly lower DSC of 0.7953 (0.7867; 0.8092).

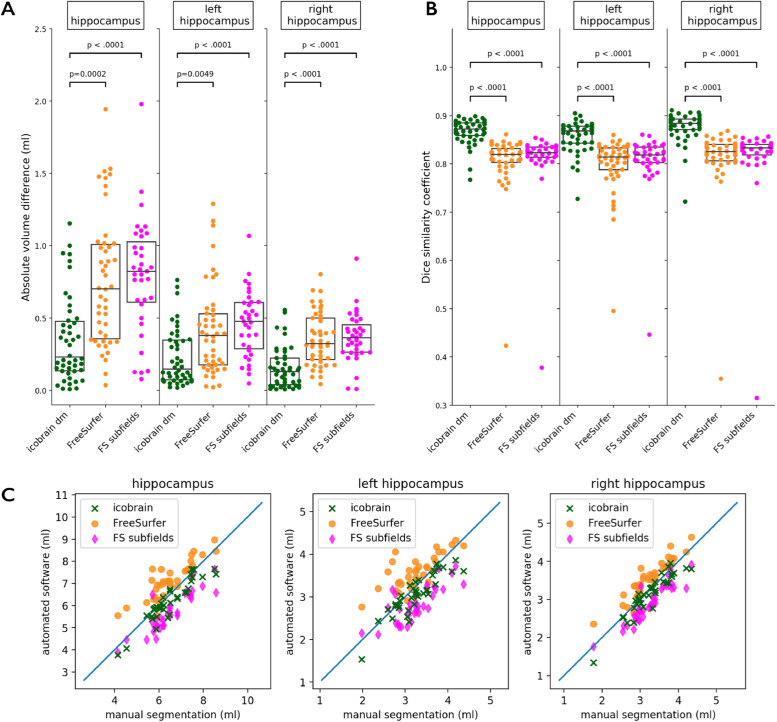

Fig. 2 illustrates the accuracy of the hippocampus segmentation obtained by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer (dataset 1.b), with panel A showing the absolute volume difference from ground truth, panel B the DSC, and panel C scatter plots of automated measurements versus manual ground truth. These results are also summarized in Table 3. The median absolute volume difference of icobrain dm was significantly lower than that of FreeSurfer's default stream and FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality, which is also supported by a significantly higher DSC for icobrain dm compared with FreeSurfer methods. It should be noted that 44/46 subjects had a DSC above 0.80 when segmented by icobrain dm compared with 35/46 subjects for FreeSurfer and 42/46 for FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality.

Fig. 2.

Accuracy of hippocampus segmentation by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer, including FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality, denoted “FS subfields”, when compared with expert manual segmentation on dataset 1.b. A. Absolute volume difference between manual and automated segmentation. B. Dice similarity coefficient between manual and automated segmentation. C. Scatterplots comparing ground truth volumes to those obtained from icobrain dm and FreeSurfer. Note: p-values are obtained from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Table 3.

Accuracy of hippocampus segmentation by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer, including FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality, denoted “FS subfields”, when compared with expert manual segmentation on dataset 1.b (only hippocampal segmentations), where volume differences are computed as ground truth segmentation volume minus volume computed automatically by icobrain dm, FreeSurfer or “FS subfields” software.

| Volume difference, ml, median (25–75 quantiles) | Absolute volume difference, ml, median (25–75 quantiles) | Dice similarity coefficient, median (25–75 quantiles) | Number of volumetric outliers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| icobrain dm | Hippocampus | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 1 |

| (−0.06; 0.46) | (0.14; 0.48) | (0.86; 0.88) | |||

| Left hippocampus | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 1 | |

| (−0.05; 0.34) | (0.07; 0.35) | (0.84; 0.88) | |||

| Right hippocampus | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.88 | 0 | |

| (−0.03; 0.21) | (0.04; 0.22) | (0.87; 0.89) | |||

| FreeSurfer | Hippocampus | −0.70 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 19 |

| (−1.01; −0.36) | (0.36; 1.01) | (0.80; 0.83) | |||

| Left hippocampus | −0.38 | 0.38 | 0.81 | 8 | |

| (−0.53; −0.16) | (0.18; 0.53) | (0.79; 0.83) | |||

| Right hippocampus | −0.32 | 0.32 | 0.83 | 17 | |

| (−0.50; −0.21) | (0.21; 0.50) | (0.81; 0.84) | |||

| FS subfields | Hippocampus | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 3 |

| (0.55; 1.03) | (0.61; 1.03) | (0.81; 0.83) | |||

| Left hippocampus | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.82 | 1 | |

| (0.24; 0.61) | (0.29; 0.61) | (0.80; 0.83) | |||

| Right hippocampus | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 2 | |

| (0.26; 0.45) | (0.26; 0.45) | (0.82; 0.84) | |||

| P values icobrain dm vs. FreeSurfer | Hippocampus | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Left hippocampus | .0002 | 0.0049 | <0.0001 | ||

| Right hippocampus | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| P values icobrain dm vs. FS subfields | Hippocampus | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Left hippocampus | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Right hippocampus | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

Note: Hippocampal volumes are not normalized for intracranial volume as the analyses are performed in native space. Manual segmentation volumes ranged from 3.8 ml to 8.6 ml. P values are obtained from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Volumetric outliers are defined as measurements below (25th percentile - 1.5 interquartile range) or above (75th percentile + 1.5 interquartile range), where these limits are obtained from the volumetric errors of icobrain dm.

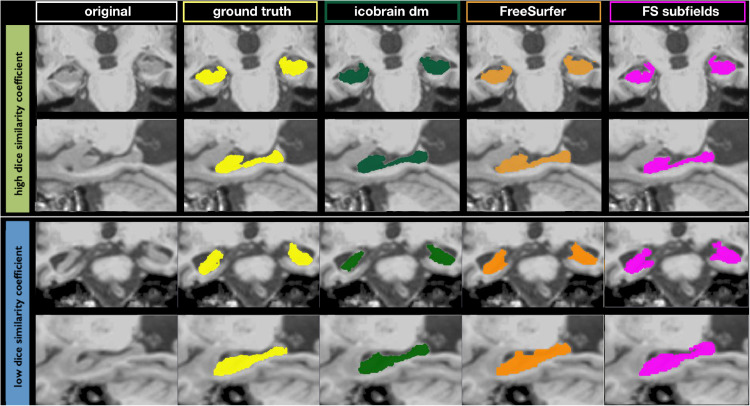

Fig. 3 shows two illustrations of hippocampus segmentations by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer with high and low DSCs, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Illustrations of hippocampus segmentation by an expert (ground truth), icobrain dm, and FreeSurfer from dataset 1.b. The top panel shows segmentations with high Dice similarity coefficient (0.90 for icobrain dm, 0.84 for FreeSurfer and 0.85 FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality), while segmentations with lower Dice similarity coefficients are presented in the bottom panel (0.79 for icobrain dm, 0.77 for FreeSurfer and 0.75 for FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfield functionality).

3.3. Reproducibility

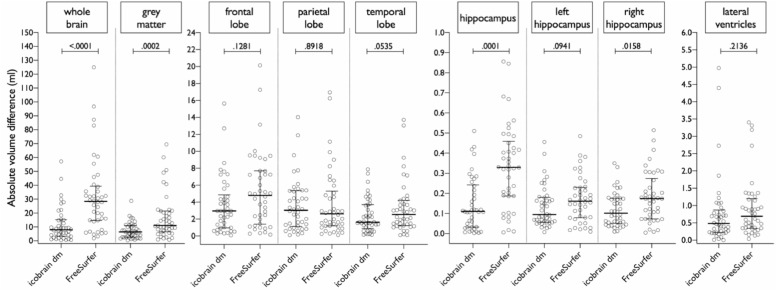

Fig. 4 illustrates the absolute volume differences between test and retest scans (dataset 2) for all measures. Detailed volume differences are presented in Table 4. The segmentations obtained by icobrain dm systematically tended to have lower volume differences than FreeSurfer, except for parietal lobe volume, with significant differences for whole brain, total gray matter, and hippocampal volumes.

Fig. 4.

Reproducibility of segmentations by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer on dataset 2, measured by the absolute volume difference between test-retest segmentations. Note: P values are obtained from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Table 4.

Reproducibility of segmentations by icobrain dm and FreeSurfer on dataset 2, measured by the absolute volume difference in millilitres between test and retest quantifications.

| icobrain dm | FreeSurfer | |

|---|---|---|

| Whole brain | 7.91 | 28.43 |

| (3.55–15.05) | (14.79–38.15) | |

| Gray matter | 6.33 | 11.01 |

| (2.62–10.73) | (6.81–21.20) | |

| Frontal lobe | 2.96 | 4.80 |

| (0.99–4.56) | (1.58–7.57) | |

| Parietal lobe | 3.60 | 2.61 |

| (1.21–5.31) | (1.20–5.01) | |

| Temporal lobe | 1.64 | 2.54 |

| (1.07–3.66) | (1.28–4.07) | |

| Hippocampus | 0.111 | 0.330 |

| (0.032–0.232) | (0.188–0.444) | |

| Left hippocampus | 0.094 | 0.161 |

| (0.057–0.176) | (0.080–0.228) | |

| Right hippocampus | 0.102 | 0.174 |

| (0.054–0.175) | (0.078–0.256) | |

| Lateral ventricles | 0.48 | 0.69 |

| (0.22–0.83) | (0.35–1.17) |

Note: Values are median (25–75th quantiles) absolute volume differences in ml (normalised for head size). FreeSurfer's hippocampal segmentations are obtained with the default stream.

3.4. Diagnostic performance

As shown in Table 5, all measures from both icobrain dm and FreeSurfer have high area under the curve (AUC) levels to distinguish AD patients from cognitively healthy controls (dataset 3). Temporal lobe volume measured by icobrain dm produced the highest AUC (0.9896), which was significantly higher than the temporal lobe AUC produced by FreeSurfer (0.9565, P = 0.04646).

Table 5.

Diagnostic performance to differentiate AD patients from age-matched controls on dataset 3.

| icobrain dm | FreeSurfer | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole brain | 0.9395 (0.8941–0.9849) | 0.9414 (0.8964–0.9864) | .9414 |

| Gray matter | 0.9386 (0.8955–0.9816) | 0.9282 (0.8730–0.9834) | .7313 |

| Frontal lobe | 0.7963 (0.7055–0.8872) | 0.8790 (0.8109–0.9472) | .0767 |

| Parietal lobe | 0.8601 (0.7848–0.9355) | 0.8960 (0.8299–0.9621) | .3242 |

| Temporal lobe | 0.9896 (0.9770–1.0000) | 0.9565 (0.9187–0.9944) | .0465 |

| Hippocampus | 0.9022 (0.8426–0.9617) | 0.9168 (0.8631–0.9706) | .2802 |

| Left hippocampus | 0.8776 (0.8000–0.9551) | 0.9055 (0.8400–0.9709) | .1735 |

| Right hippocampus | 0.8965 (0.8365–0.9565) | 0.8885 (0.8253–0.9517) | .6343 |

| Lateral ventricles | 0.8899 (0.8180–0.9617) | 0.8488 (0.7660–0.9315) | .0013 |

Note: Values are areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (95% confidence interval). DeLong tests were used to test whether AUC levels differed significantly between icobrain dm and FreeSurfer. FreeSurfer's hippocampal segmentations are obtained with the default stream.

4. Discussion

In this paper, the automated method icobrain dm for measuring brain volumes is presented and compared to the widely used FreeSurfer. In order to assess the use of this method in clinical practice on MRI scans of individual dementia patients, the reliability of the method is evaluated in terms of accuracy, reliability and diagnostic performance of all measures. Results are compared to FreeSurfer, a well-validated and extensively used method for measuring brain volumes in clinical studies and trials. icobrain dm and FreeSurfer results on dataset 1.a demonstrated bias in most volumes compared to manual delineations. A systematic bias is not dangerous as such, because volumes obtained with a certain automated software would typically only be compared with the same software between patient groups or between patients and healthy controls. A reason for bias to manual delineations could be the absence of partial volume effect in the manual ground truth. Both icobrain dm and FreeSurfer compute theirs volumes from probability maps, where the voxels close to the brain contour are partly brain tissue, partly CSF, without sharp edges.

Hippocampus segmentation showed however a divergent trend between the 2 automated methods, with FreeSurfer's default stream overestimating most volumes, and icobrain dm slightly underestimating them. On the other hand, FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfields segmentation module (Iglesias et al., 2015), which is currently included in FreeSurfer's development version and thus is not yet the default algorithm, underestimates the considered manual segmentations slightly more than icobrain dm. A recent paper (Ataloglou et al., 2019) reported state-of-the-art hippocampus segmentation results using deep convolutional neural network (CNN) ensembles, reaching a Dice score of 0.88 on the same MICCAI 2012 challenge dataset. However, the authors had to tune their CNN with transfer learning on a training subset of the MICCAI 2012 challenge dataset in order to reach these maximal performance results. Deep learning is increasingly superior to classical brain segmentation approaches, but it is limited by the amount, the diversity and the quality of the data used for training. icobrain dm results on dataset 1.b demonstrated a small measurement error for hippocampus segmentation, with a median absolute volume difference from ground truth of 0.230 ml. The similarity with ground truth was generally high, with a median DSC of 0.87 and 44/46 segmentations with a DSC above 0.80. The accuracy of icobrain dm was significantly higher than that of both the default hippocampal segmentation in FreeSurfer 6.0 recon-all stream and FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfields segmentation module (Iglesias et al., 2015), confirming the same trends observed in dataset 1.a.

Bias in hippocampal volumes between automated methods and manual annotations is not surprising, since not all methods and all manual raters use the same definition of the hippocampal borders seen on MRI. The recent EADC-ADNI harmonized protocol (Boccardi et al., 2015), which is used for the multi-atlas approach of icobrain dm, is more clearly defined compared to prior protocols, but it differs from the Center for Morphometric Analysis (CMA) guidelines (Filipek et al., 1994) underlying FreeSurfer's probabilistic atlas used by the default recon-all stream. Other recent studies such as (Schmidt et al., 2018) found that FreeSurfer 6.0 overestimates the hippocampal volume by 20% compared to manual raters, which is explained by the fact that FreeSurfer includes further caudal regions, resulting in larger tails, as well as some voxels between hippocampus and lateral ventricles. On the other hand, the newer FreeSurfer hippocampal subfields segmentation module (Iglesias et al., 2015) is based on a quite different definition of the hippocampal formation at the subregion level, using ultra-high resolution ex vivo MRIs. The total hippocampal volume obtained with this approach underestimates the volumes obtained from manual segmentations in both accuracy datasets considered in this paper. A potential explanation for this bias towards smaller volumes is that the hippocampus subfield atlas was built using elderly subjects, and was based on a detailed ex vivo MRI delineation protocol that cannot be performed on in vivo brain scans.

The test-retest error on dataset 2 was lower for icobrain dm for all measures except parietal lobe volume, although these differences were significant only for whole brain, total gray matter, and hippocampal volumes. Regarding hippocampal volume, the average test-retest absolute volume difference of the hippocampus is 0.111 ml, which represents 1.20% of the average icobrain dm hippocampal volume (measured by icobrain dm; test and retest combined). As such, the measurement error is below the average annual hippocampal atrophy rates of 1.41% in healthy individuals (Barnes et al., 2009). For FreeSurfer's hippocampal subfields segmentation, which we explored in the accuracy experiments (Iglesias et al., 2015), Iglesias et al. (2016) reported test-retest reliability of around 2.5% for the whole left and right hippocampus.

It should also be noted that test-retest exercises are usually performed with datasets on the same scanner. In this manuscript we evaluated test-retest reliability on different scanner types. This increases variability and is better in line with clinical practice.

Finally, when using dataset 3, we found that all measures achieve high diagnostic performance levels when discriminating AD patients from cognitively healthy controls. The temporal lobe volume measured by icobrain dm reached the highest diagnostic performance level (AUC = 0.9896). Although hippocampal atrophy is considered the most disease-specific for Alzheimer's disease, it is not surprising that this structure has slightly lower diagnostic performance compared to the temporal lobe volume, since lower volumes (such as hippocampus) are likely affected by proportionally higher measurement errors. Moreover, not all subjects had severe dementia, as dataset 3 consisted of mild-moderate probable AD.

Of note, the frontal lobe produced the lowest diagnostic performance levels, with FreeSurfer showing stronger differences compared to icobrain dm. In fact icobrain dm finds the frontal cortex volumes in this particular dataset as being close to normal values for that age. As this region is the least of all included measures affected in AD (McKhann et al., 2011), this result is in line with our expectations.

We conclude that due to its low measurement error, icobrain dm could be of added value to the clinical diagnostic practice of AD patients. In future studies the performance of the measures to diagnose (very) early stages of AD as well as to distinguish between different dementia illnesses should be further investigated.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hanne Struyfs: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Diana Maria Sima: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Melissa Wittens: Resources, Data curation, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Annemie Ribbens: Methodology, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Nuno Pedrosa de Barros: Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Thanh Vân Phan: Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Maria Ines Ferraz Meyer: Resources, Data curation, Software. Lene Claes: Resources, Data curation. Ellis Niemantsverdriet: Resources, Data curation. Sebastiaan Engelborghs: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Wim Van Hecke: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Dirk Smeets: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The following authors are employed (or have been employed at the time of performing the work relevant for this paper) by icometrix: Hanne Struyfs, Diana M. Sima, Annemie Ribbens, Nuno Pedrosa de Barros, Thanh Vân Phan, Lene Claes, Maria Ines Ferraz Meyer, Wim Van Hecke, Dirk Smeets. Melissa Wittens and Ellis Niemantsverdriet have no competing interests. Sebastiaan Engelborghs has received unrestricted research grants from Janssen Pharmaceutica NV and ADx Neurosciences (paid to institution).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded in part by the agency of Flanders Innovation & Intrepreneurship (VLAIO), the Flemish Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT 140262), the Interreg V programme Flanders-The Netherlands of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (Herinneringen/Memories project), the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement numbers 666992 (EUROPOND) and 765148 (TRABIT).

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the OASIS-3 database. The OASIS investigators did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. The OASIS-3 dataset is made available through support from grants. The authors thank Andrew J. Worth from Neuromorphometrics for providing the data of the MICCAI 2012 challenge on multi-atlas labelling. The authors acknowledge the staff of the memory clinic of the neurology department of Hospital Network Antwerp (ZNA) Middelheim and Hoge Beuken for their contribution to dataset 1.b. Data used in the preparation of this article were also obtained from the MIRIAD database. The MIRIAD investigators did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. The MIRIAD dataset is made available through the support of the UK Alzheimer's Society (Grant RF116). The original data collection was funded through an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline (Grant 6GKC).

References

- Ataloglou D., Dimou A., Zarpalas D., Daras P. Fast and precise hippocampus segmentation through deep convolutional neural network ensembles and transfer learning. Neuroinformatics. 2019 Oct;17(4):563–582. doi: 10.1007/s12021-019-09417-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J., Bartlett J.W., van de Pol L.A., Loy C.T., Scahill R.I., Frost C. A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;30(11):1711–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J., Foster J., Boyes R.G., Pepple T., Moore E., Schott J.M. A comparison of methods for the automated calculation of volumes and atrophy rates in the hippocampus. Neuroimage. 2008;40(4):1655–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi M., Bocchetta M., Apostolova L.G., Barnes J., Bartzokis G., Corbetta G. Delphi definition of the eadc-adni harmonized protocol for hippocampal segmentation on magnetic resonance. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2015;11(2):126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi M., Ganzola R., Bocchetta M., Pievani M., Redolfi A., Bartzokis G. Survey of protocols for the manual segmentation of the hippocampus: preparatory steps towards a joint EADC-ADNI harmonized protocol. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(Suppl 3):61–75. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi M., Laakso M.P., Bresciani L., Galluzzi S., Geroldi C., Beltramello A. The MRI pattern of frontal and temporal brain atrophy in fronto-temporal dementia. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24(1):95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco P., Redolfi A., Bocchetta M., Ferrari C., Mega A., Galluzzi S. The impact of automated hippocampal volumetry on diagnostic confidence in patients with suspected Alzheimer’s disease: a european alzheimer’s disease consortium study. Alzheimer’s dementia. 2017;13(9):1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso M.J.NiftySeg: statistical segmentation and label fusion software package. 20122019 FEB 5th [cited 2019 FEB 26th]; Available from: http://cmictig.cs.ucl.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/NiftySeg.

- Cardoso M.J., Leung K., Modat M., Keihaninejad S., Cash D., Barnes J. STEPS: similarity and truth estimation for propagated segmentations and its application to hippocampal segmentation and brain parcelation. Med. Image Anal. 2013;17(6):671–684. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D., Fox N.C., Scahill R.I., Crum W.R., Whitwell J.L., Leschziner G. Patterns of temporal lobe atrophy in semantic dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49(4):433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui H.C., Victoroff J., Margolin D., Jagust W., Shankle R., Katzman R. Criteria for the diagnosis of ischemic vascular dementia proposed by the state of California Alzheimer's disease diagnostic and treatment centers. Neurology. 1992;42(3):473. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.473. - [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey J., Hana G., Russell T., Price J., McCaffrey D., Harezlak J. Reliability and validity of MRI-based automated volumetry software relative to auto-assisted manual measurement of subcortical structures in HIV-infected patients from a multisite study. Neuroimage. 2010;51(4):1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill V., Franco A.R., Pinho M.S. Automated methods for hippocampus segmentation: the evolution and a review of the state of the art. Neuroinformatics. 2015;13(2):133–150. doi: 10.1007/s12021-014-9243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doring T.M., Kubo T.T., Cruz L.C.H., Juruena M.F., Fainberg J., Domingues R.C. Evaluation of hippocampal volume based on MR imaging in patients with bipolar affective disorder applying manual and automatic segmentation techniques. J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2011;33(3):565–572. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B. The emergence of a new conceptual framework for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):1059–1066. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S., Pruessner J., Collins D. Appearance-based segmentation of medial temporal lobe structures. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):515–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A.C., Marrett S., Neelin P., Collins L., Worsley K., Dai W. Anatomical mapping of functional activation in stereotactic coordinate space. Neuroimage. 1992;1(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/1053-8119(92)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PA1 Filipek, C Richelme, Kennedy D.N., Jr Caviness VS. The young adult human brain: an MRI-based morphometric analysis. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4(4):344–360. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.4.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Salat D.H., Busa E., Albert M., Dieterich M., Haselgrove C. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias J.E., Augustinack J.C., Nguyen K., Player C.M., Player A., Wright M., Roy N., Frosch M.P., Mc Kee A.C., Wald L.L., Fischl B., Van Leemput K. Hippocampus: a computational atlas of the hippocampal formation using ex vivo, ultra-high resolution MRI: application to adaptive segmentation of in vivo MRI. Neuroimage. 2015;115:117–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias J.E., Van Leemput K., Augustinack J.C., Insausti R., Fischl B., Reuter M. Bayesian longitudinal segmentation of hippocampal substructures in brain MRI using subject-specific atlases. Neuroimage. 2016;141:542–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S., Sima D.M., Ribbens A., Cambron M., Maertens A., Van Hecke W. Automatic segmentation and volumetry of multiple sclerosis brain lesions from MR images. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;8:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy K.M., Erickson K.I., Rodrigue K.M., Voss M.W., Colcombe S.J., Kramer A.F. Age-related differences in regional brain volumes: a comparison of optimized voxel-based morphometry to manual volumetry. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;30(10):1657–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A., Tourville J. 101 labeled brain images and a consistent human cortical labeling protocol. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:171. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone I.B., Cash D., Ridgway G.R., MacManus D.G., Ourselin S., Fox N.C. MIRIAD—Public release of a multiple time point Alzheimer's MR imaging dataset. Neuroimage. 2013;70:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith I.G., Boeve B.F., Dickson D.W., Halliday G., Taylor J.P., Weintraub D. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G., Drachman D., Folstein M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modat M., Ridgway G.R., Taylor Z.A., Lehmann M., Barnes J., Hawkes D.J., Fox N.C., Ourselin S. Fast free-form deformation using graphics processing units. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;98:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary D., Snowden J.S., Gustafson L., Passant U., Stuss D., Black S. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin X., Turck N., Hainard A., Tiberti N., Lisacek F., Sanchez J.C. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman G.C., Tatemichi T.K., Erkinjuntti T., Cummings J.L., Masdeu J.C., Garcia J.H. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H.J., Gorno–Tempini M.L., Goldman W., Perry R., Schuff N., Weiner M. Patterns of brain atrophy in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2002;58(2):198–208. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H.J., Kramer J.H., Gorno-Tempini M.L., Schuff N., Weiner M., Miller B.L. Patterns of cerebral atrophy in primary progressive aphasia. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10(1):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M.F., Storrs J.M., Freeman K.B., Jr Jack CR, Turner S.T., Griswold M.E., Jr Mosley TH. A comparison of manual tracing and FreeSurfer for estimating hippocampal volume over the adult lifespan. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39(6):2500–2513. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s dementia. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team R . RStudio Inc.; Boston: 2016. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. (Version 1.0.136) [Software] [Google Scholar]

- Venables W.N., Ripley B.D. 4th ed. Springer; New York: 2002. Modern Applied Statistics With S. [Google Scholar]