Abstract

The fibrinolytic system is critical during the onset of fibrinolysis, a fundamental mechanism for fibrin degradation. Both tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) trigger fibrinolysis, leading to proteolytic activation of plasminogen to plasmin and subsequently fibrin proteolysis. This system is regulated by several inhibitors; plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), the most studied, binds to and inactivates both tPA and uPA. Through the action of plasmin, this system regulates several physiological processes: embryogenesis, activation of inflammatory cells, cell proliferation and death, synaptic plasticity, wound healing, and others. The deregulated intervention of fibrinolysis in the pathophysiology of various diseases has been widely studied; findings of altered functioning have been reported in different chronic non-communicable diseases (NCD), reinforcing its pleiotropic character and the importance of its physiology and regulation. The evidence indicates that fundamental elements of the fibrinolytic system, such as tPA and PAI-1, show a circadian rhythm in their plasmatic levels and their gene expression are regulated by circadian system elements, known as clock genes – Bmal, Clock, Cry-, and accessory clock genes such as Rev-Erb and Ror. The disturbance in the molecular machinery of the clock by exposure to light during the night alters the natural light/dark cycle and causes disruption of the circadian rhythm. Such exposure affects the synchronization and functioning of peripheral clocks responsible for the expression of the components of the fibrinolytic system. So, this circadian disturbance could be critical in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases where this system has been found to be deregulated.

Keywords: non-communicable diseases, fibrinolytic system, PAI-1, clock genes, chronodisruption, prothrombotic phenotype

Circadian Rhythms, Clock Genes, and Their Close Relationship With Hemostasis and Fibrinolysis

The temporal organization of a living being is influenced by environmental stimuli and by internal biological clocks that are endogenously regulated in all living things. From an evolutionary point of view, events such as day and night, represented by light/dark cycles, were incorporated as a relevant time mark to predict environmental changes and as an anticipatory mechanism to perform and optimize activity/rest cycles (Mohawk et al., 2013). Circadian rhythms are intrinsic biological oscillations with a period close to 24 h; in mammals, they are driven by the circadian synchronization system (Albrecht, 2012). This system has a hierarchical organization; it is composed of the pacemaker or central clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which is synchronized through the environmental light signals that proceed from the retina and are transported by the retinohypothalamic tract (Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010). The central clock, in turn, synchronizes peripheral clocks located in virtually all tissues and organs through nerve and/or endocrine signals (Schibler et al., 2015). Circadian rhythms are generated at cell level through transcriptional/translational loops (central and accessories loop). Interconnected and self-regulated by positive and negative feedback, these loops are composed for transcription factors collectively referred to as clock genes (Mohawk et al., 2013). The central loop is composed of the CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer, which promotes the rhythmic expression of the repressor proteins PER1-3 and CRY1-2 through E-box sites. Subsequently, PER and CRY translocate to the nucleus once they have been modified post-translationally, feeding back and limiting their own expression by displacing the CLOCK:BMAL1 from their promoter site. A cycle of this negative and positive feedback lasts approximately 24 h, thus generating circadian rhythmicity (Curtis et al., 2014; Takahashi, 2016).

The CLOCK:BMAL1 also promotes rhythmic transcription of the accessory loop components, such as the REV-ERBα/β nuclear receptor, which represses the transcription of the Bmal1 gene by binding to the retinoid-related orphan receptor response element (RORE) in the promoter site of Bmal1 (Partch et al., 2014; Honma, 2018). Other genes that structure the accessory loop are retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs); Rorα/β/γ have been shown to activate the transcription of Bmal1 through the binding of their respective proteins to RORE sites (Guillaumond et al., 2005). In addition, RORs modulate the expression of important components of the central loop such as CLOCK and CRY (Ueda et al., 2005; Takeda et al., 2012), which indicates that they are strongly involved in the regulation of the expression of clock genes and therefore of molecular machinery functions (Mazzoccoli et al., 2012a). The clock genes of the central and accessory loop regulate the rhythmic expression of other target genes called clock-controlled genes (CCGs), which in turn are related to multiple physiological functions such as behavior, metabolism, hemostasis, and immunity (Liu et al., 2008; Jetten, 2009; Shimba et al., 2011; Mavroudis et al., 2018). The central loop is also regulated by another accessory pathway, which includes the D-box albumin transcriptional activator binding protein (DBP), transcriptionally regulated through an E-box site, and the binding protein NFIL3, transcriptionally regulated through a RORE site. The DBP and NFIL3 proteins regulate positively and negatively, respectively the expression of genes that have D-box sites at their promoter site, such as Per, Cry, or Rev-Erb and other CCGs (Ueda et al., 2005; Curtis et al., 2014; Man et al., 2016; Mavroudis et al., 2018). Other data indicate that the mechanisms by which CLOCK:BMAL1 regulates the transcription of core clock genes do not apply to CCGs and suggest that the primary function of CLOCK:BMAL1 is to regulate the chromatin landscape at its enhancers to facilitate the binding of other transcription factors. This implies that CCG expression would be indirect, based on the interaction between the circadian clock and other signaling pathways (Trott and Menet, 2018; Beytebiere et al., 2019).

The circadian clock literally affects all physiological functions and behaviors, contributing significantly to the production and maintenance of endocrine rhythms modulating the levels of endocrine factors as well as the ability of the tissues to respond to these stimuli throughout the day (Richards and Gumz, 2013; Gamble et al., 2014; Challet, 2015). The evidence suggests that specific clock genes regulate different functions of the physiology of innate and adaptive immune cells (Silver et al., 2012; Casanova-Acebes et al., 2013; Pritchett and Reddy, 2015; Scheiermann et al., 2018), indicating that the regulation of immune response is under circadian control. Furthermore, the overall evidence shows that there is a mutual relationship: The clock controls some crucial metabolic pathways, and the metabolism feeds back to the clock machinery, synchronizing functions such as the production and expenditure of energy with the circadian patterns of the expression of metabolic genes in synchrony with the light/dark cycles, replenishing the proteins and enzymes during the resting phase that are needed to perform physiological functions in optimal conditions during the activity phase (Bellet and Sassone-Corsi, 2010; Mazzoccoli et al., 2012b; Masri et al., 2014). Moreover, circadian rhythms are important regulators of cardiovascular physiology; peripheral clocks are present in each of the types of cardiovascular cells, regulating various physiological functions such as endothelial function, blood pressure, and heart rate (Crnko et al., 2019). In relation to hemostasis, robust circadian oscillations in the number of circulating platelets and in the markers of platelet-endothelial aggregation and adhesion have been demonstrated (Scheer et al., 2011). A clear circadian expression of prothrombotic factors such as von Willebrand factor has also been shown, displaying maximum expression during the activity phase in humans and rodents, while on the other hand demonstrating a clear regulation of fibrinogen expression through clock genes (Somanath et al., 2011). Also, parameters of the coagulation system, such as prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), displayed a circadian rhythm, with the shortest PT being recorded late at night and early in the morning (Budkowska et al., 2019). All the expression profiles of circadian hemostasis previously described favor a prothrombotic phenotype when the circadian function of the molecular clock is deregulated.

Practically all tissues and organs have peripheral clocks, synchronized by powerful environmental signals such as light/dark cycles. Nowadays, modern society is further exposed to interruption of the synchrony of circadian rhythms through activities such as shift work, work at night, or chronic jet-lag, promoting a chronodisruption that has proven consequences for human health (Erren and Reiter, 2009, 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising to see that alterations in the circadian rhythm are involved in an increasing number of various chronic diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), and cancer (Haus and Smolensky, 2006; Scheer et al., 2009; Pietroiusti et al., 2010; Stevens et al., 2011; Plano et al., 2017). Interestingly, in several of these chronic diseases, the deregulation of the fibrinolytic system is also demonstrated in some of its components (Medcalf, 2007; Oishi, 2009; Godier and Hunt, 2013; Draxler and Medcalf, 2015; Svenningsen et al., 2017). In particular, an association between CVDs and an alteration in the levels of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) expression and mainly plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) has been demonstrated, the latter being studied as a possible marker of cardiovascular risk (Declerck and Gils, 2013; Tofler et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2018) and senescence (Eren et al., 2014; Yamamoto et al., 2014; Vaughan et al., 2017).

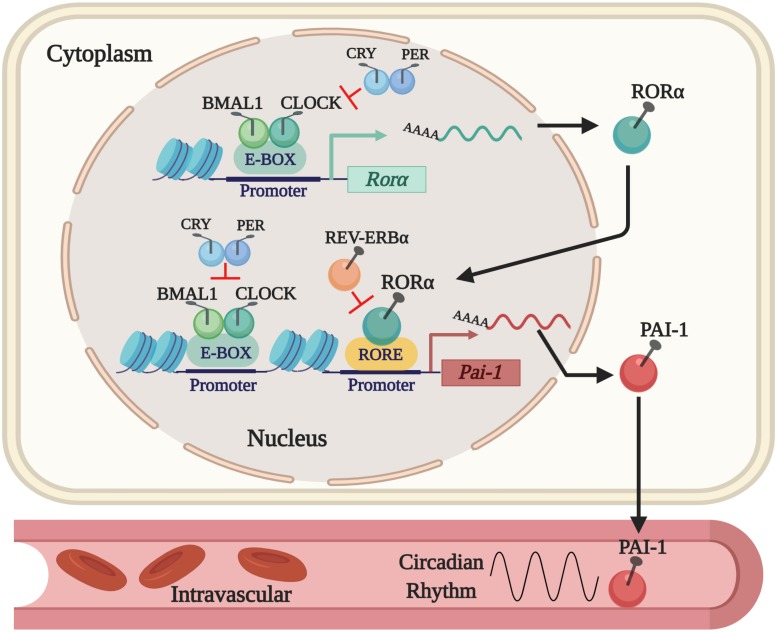

Fibrinolytic Activity and Its Regulation Through Clock Genes

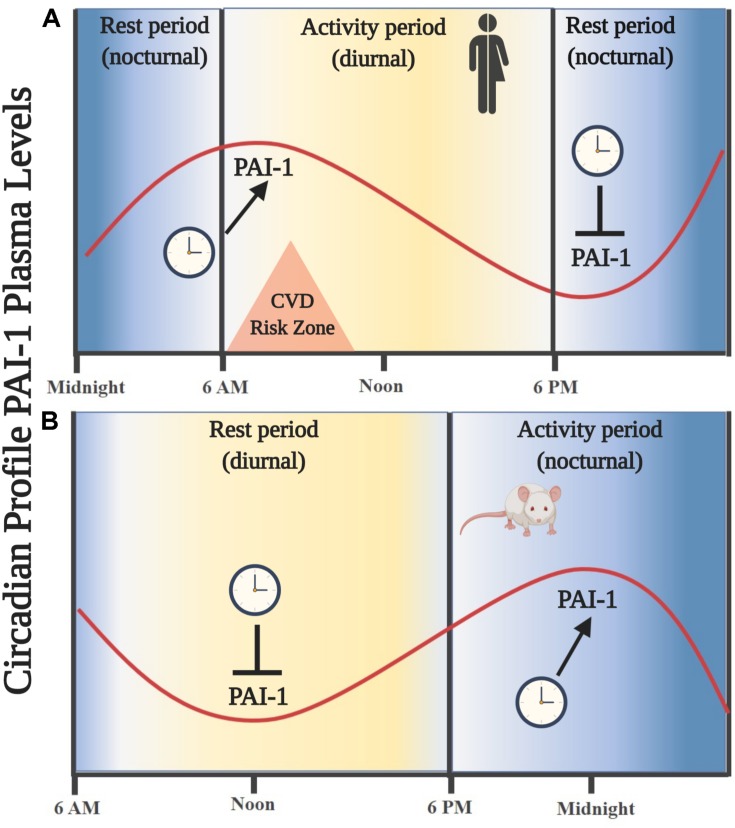

Thus far, we know that tPA and PAI-1 plasma levels oscillate robustly in circadian form in humans and rodents, decreasing and increasing, respectively, during the activity phase in both species, contributing to a state of hypofibrinolysis during this period (Angleton et al., 1989; Andreotti and Kluft, 1991; Ohkura et al., 2007; Scheer and Shea, 2014; Budkowska et al., 2019). This feature allows rodent models to be used for investigating the mechanisms that regulate fibrinolysis and its possible damage (see Figure 1). The rise in plasma PAI-1 levels during the beginning of the activity phase could explain the higher incidence of myocardial infarctions and strokes in humans in the morning (Pavlov and Ćelap, 2019). Experimental animal and cell models have shown that the expression of the Pai-1 gene is directly regulated by clock proteins, which act as transcription factors either by stimulating or repressing its expression. In cell models, it has been shown that both heterodimers – CLOCK/BMAL1 and CLOCK/BMAL2 – promote the expression of the Pai-1 gene through two E-box elements, located at its promoter site (Maemura et al., 2000; Schoenhard et al., 2003; Oishi et al., 2007). Moreover, CLOCK seems to be a positive regulator for the expression of the Pai-1 mRNA because it has been found to decrease its expression levels and have no circadian rhythm when the Clock gene has been silenced by a small interfering RNA (siRNA) in endothelial cell culture and in mice (Cheng et al., 2011). The same occurs in a mutant mouse model for CLOCK (Ohkura et al., 2006) or when PER2 is overexpressed (Oishi et al., 2009). Regulation through other clock genes such as CRY1/2 has shown that they act as negative regulators in the expression of the Pai-1 mRNA and also determine the characteristic plasma oscillatory pattern of PAI-1, because an increased and arrhythmic plasmatic expression have been observed in CRY1/CRY2–/– mice (N. Ohkura et al., 2006). In addition, the Pai-1 transcript is promoted by RORα and repressed by REV-ERBα by binding to response elements related to the orphan receptor (RORE sites) at its promoter site (Wang et al., 2006). These clock genes (through their proteins RORα and REV-ERBα) regulate the expression of CLOCK:BMAL1 and other CCGs (Mohawk et al., 2013; Curtis et al., 2014; Takahashi, 2016). In fact, the evidence described above demonstrates that Pai-1 is a CCG (see Figure 2). There are other important transcriptional regulations, such as the sirtuins (SIRTs), which modulate the expression of various clock genes in a circadian manner, repressing transcription through their histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and counteracting the CLOCK histone acetylase (HAT) protein activity, which in turn promotes the expression of clock genes and CCGs (Bellet and Sassone-Corsi, 2010), thus balancing the transcriptional activity of the circadian system. There is also evidence to suggest that Pai-1 may be epigenetically modified through a mechanism that involves SIRT1, a class III chromatin histone deacetylase (SIRTUIN1), promoting heterochromatin formation and Pai-1 gene silencing, specifically by direct acetylation of histone 4 lysine 16 (H4K16) at its promoter site (Lopez-Legarrea et al., 2013; Wan et al., 2014).

FIGURE 1.

Oscillations in the circulating levels of PAI-1 are directed by an endogenous circadian synchronization system. (A) Circadian rhythm of PAI-1 in humans. An increase in circulating levels is observed leaving the resting phase (nocturnal), showing a maximum amplitude entering the activity phase (diurnal) during the first hours of the morning. (B) Circadian rhythm of PAI-1 in rodents. An increase in circulating levels is observed leaving the resting phase (diurnal), showing a maximum amplitude in the activity phase (nocturnal). Similarity is noted in the oscillation profile of circulating PAI-1 in the phase of activity/rest of both species; thus, a rodent model is useful for the study of key components of the fibrinolytic system.

FIGURE 2.

The current regulatory mechanism proposed for the expression of PAI-1 as a CCG. The expression of the Pai-1 gene is positively regulated by the CLOCK/BMAL1 dimer that binds to E-box elements and by RORα that binds to RORE sites in its promoter site. Expression is repressed by displacing the CLOCK/BMAL1 dimer by PER/CRY and by REV-ERBα, which competes with RORα for the RORE sites in the PAI-1 promoter.

Discussion

Disturbance in the Molecular Machinery of the Clock: Its Effect on Thrombogenesis and Fibrinolysis Through PAI-1

As described above, the fibrinolytic system is an important endogenous defense system against intravascular thrombosis. The evidence indicates that its main modulator is the PAI-1 inhibitor, which is currently classified as an independent risk factor for CVD (Tofler et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2018). On the other hand, the circadian expression of PAI-1 is regulated by the molecular machinery of peripheral clocks; various clock genes determine both their level of expression and circadian rhythmicity. This suggests that an alteration in the expression of the clock genes, by means of genetic ablations DNA mutations or by circadian disruption by alterations of the dark/light cycles, could promote a decrease in fibrinolytic activity or hypofibrinolysis, thereby increasing the predisposition to the development of CVD.

In recent years, it has been reported that disruption models of the Bmal1 clock gene in mice develop various characteristics that combined describe a prothrombotic phenotype. One study that used mice deficient in Bmal1 (Bmal1–/–) showed significant differences from the control group: shorter times of cessation of tail bleeding, significantly shorter arterial occlusion times after an injury, increased plasma fibrinogen levels and a significant increase in plasma levels, and an absence of a circadian pattern for PAI-1 (Somanath et al., 2011). Other models have confirmed the progression of a prothrombotic state in knockout mice (KO) for Bmal1 during the development of aging: The results showed shorter prothrombin times, increased platelet count, decreased endothelial production of nitric oxide and thrombomodulin expression (Hemmeryckx et al., 2011), confirming a close functional relationship between the central loop of the clock and the regulation of the hemostasis. Later studies also showed that Bmal1 deficiencies (Bmal1–/– mice) clearly disrupt the daily rhythm in the expression of relevant coagulation and fibrinolysis factors. Specifically in the liver, an increase in the gene expression of fibrinogen, tissue factor, protein C, and Pai-1 have been observed while tPA is decreased; however, plasma levels of PAI-1 are reduced, which disagrees with reports by Somanath et al., where they were found to be increased. This discrepancy may be related to differences in the light/dark protocols in which the mice were kept (Somanath et al., 2011; Hemmeryckx et al., 2019).

The effects found in the liver are interesting because this organ is the most important in the synthesis of coagulation and fibrinolysis factors (Dimova and Kietzmann, 2008; Leebeek and Rijken, 2015). Furthermore, it has often been described as an important peripheral circadian clock (Reinke and Asher, 2016; Tahara and Shibata, 2016; Zwighaft et al., 2016); therefore, any desynchronization or disruption of its circadian rhythm could have side effects on the physiological functions it performs.

On the other hand, CLOCK is also important for maintaining the diurnal variation of thrombogenesis. The mutation of CLOCK in mice (CLOCKmut) alters the fibrinolytic system; total and active plasma levels of PAI-1 are elevated and tPA is reduced. In addition, these effects would be related to the small but significant increase in vascular occlusion time observed in this experimental model (Westgate et al., 2008). Interestingly, in patients with acute coronary syndrome, CLOCK and PAI-1 were overexpressed in peripheral blood macrophage cells, suggesting that CLOCK might play an important role in the progression of atherosclerotic plaques (Jiang et al., 2018). Taken together, these results show that clock genes control the expression of key components in hemostatic function and the fibrinolysis system, which leads to an increased risk of developing a prothrombotic phenotype and thus an increased risk of harmful cardiovascular events.

Update on Unusual Exposure to Artificial Light and Its Impact on Fibrinolytic Activity

A reduced fibrinolytic activity due to an increase in the expression of PAI-1 is a characteristic risk factor for CVD due to its role in vascular homeostasis (Mavri et al., 2004; Oishi, 2009). In addition, as described above, its plasma levels have a typical circadian rhythm and its gene expression is regulated by clock genes; therefore, PAI-1 is a component capable of being disturbed through a circadian disruption. It is known that the light is a dominant stimulus for training circadian rhythms in mammals, and exposure to light at inappropriate times such as during the resting stage could alter the physiology of tissues, organs and systems (Roenneberg et al., 2013; Plano et al., 2017), including the fibrinolytic system. To date, the studies that are known have examined the experimental effect of a chronic alteration of the photoperiod on the expression of PAI-1. For this, mouse models have been used (rodents and humans have the same circadian profile for PAI-1 and tPA in the rest/activity cycle), exposed to a temporary desynchronization of the endogenous circadian clock, imitating the working schemes of rotating shifts. The results show that the hepatic expression of Pai-1 and its plasma levels increase significantly while the tPA expression decreases. Additionally, increased levels of plasma corticosterone were found, suggesting a relationship between the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the expression of Pai-1 (Oishi and Ohkura, 2013). In another study, alterations in the hepatic expression of clock genes such as Clock, Bmal1, and Per1 were found in mice exposed to artificial light pulses during the night phase, and in the same way, an increase in both transcriptional hepatic expression and plasma protein of PAI-1 was observed (Aoshima et al., 2014). In humans, it seems that the indispensable requirement for an increase in PAI-1 levels is a chronic circadian desynchronization because short-term circadian misalignment lowers the 24-h PAI-1 levels (Morris et al., 2016).

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that a disturbance of the endogenous circadian rhythm mediated by the photoperiod alteration induces a state of hypofibrinolysis, mainly by promoting an alteration in the expression of PAI-1 and tPA, due to its direct regulation by the circadian synchronization system. Additional studies on animal models and humans are needed to determine the association of these findings on the origin and/or development of CVD and other chronic diseases in which PAI-1 and tPA are involved in their pathophysiology, in order to prevent the appearance of chronic diseases in adulthood due to exposure to chronodisruption.

Author Contributions

PC wrote the first draft and developed the final version of the manuscript; NM, CI, and PB conducted a critical review for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- CCG

clock-controlled gene

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- NCD

non-communicable disease

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- ROR

retinoid-related orphan receptor

- RORE

ROR-response elements

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Fellowship No. 21171387 from the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT) and Grant No. 11170245 from the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico, Chile (FONDECYT), Chile.

References

- Albrecht U. (2012). Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron 74 246–260. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti F., Kluft C. (1991). Circadian variation of fibrinolytic activity in blood. Chronobiol. Int. 8 336–351. 10.3109/07420529109059170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angleton P., Chandler W. L., Schmer G. (1989). Diurnal variation of tissue-type plasminogen activator and its rapid inhibitor (PAI-1). Circulation 79 101–106. 10.1161/01.CIR.79.1.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshima Y., Sakakibara H., Suzuki T., Yamazaki S., Shimoi K. (2014). Nocturnal light exposure alters hepatic Pai-1 expression by stimulating the adrenal pathway in C3H mice. Exp. Anim. 63 331–338. 10.1538/expanim.63.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellet M. M., Sassone-Corsi P. (2010). Mammalian circadian clock and metabolism – The epigenetic link. J. Cell Sci. 123(Pt 22), 3837–3848. 10.1242/jcs.051649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beytebiere J. R., Greenwell B. J., Sahasrabudhe A., Menet J. S. (2019). Clock-controlled rhythmic transcription: is the clock enough and how does it work? Transcription 10 1–10. 10.1080/21541264.2019.1673636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budkowska M., Lebiecka A., Marcinowska Z., Woźniak J., Jastrzębska M., Dołęgowska B. (2019). The circadian rhythm of selected parameters of the hemostasis system in healthy people. Thrombosis Res. 182 79–88. 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Acebes M., Pitaval C., Weiss L. A., Nombela-Arrieta C., Chèvre R., A-González N., et al. (2013). XRhythmic modulation of the hematopoietic niche through neutrophil clearance. Cell 153:1025. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challet E. (2015). Keeping circadian time with hormones. Diabetes. Obes. Metab. 17 76–83. 10.1111/dom.12516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Jiang Z., Zou Y., Chen C., Wang Y., Liu Y., et al. (2011). Downregulation of Clock in circulatory system leads to an enhancement of fibrinolysis in mice. Exp. Biol. Med. 236 1078–1084. 10.1258/ebm.2011.010322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnko S., Du Pré B. C., Sluijter J. P. G., Van Laake L. W. (2019). Circadian rhythms and the molecular clock in cardiovascular biology and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16 437–447. 10.1038/s41569-019-0167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A. M., Bellet M. M., Sassone-Corsi P., O’Neill L. A. J. (2014). Circadian clock proteins and immunity. Immunity 40 178–186. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck P. J., Gils A. (2013). Three decades of research on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: a multifaceted serpin. Semin. Thrombosis Hemostasis 39 356–364. 10.1055/s-0033-1334487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova E. Y., Kietzmann T. (2008). Metabolic, hormonal and environmental regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) expression: lessons from the liver. Thrombosis Haemostasis 100 992–1006. 10.1160/TH08-07-0490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draxler D. F., Medcalf R. L. (2015). The fibrinolytic system-more than fibrinolysis? Transf. Med. Rev. 29 102–109. 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren M., Boe A. E., Klyachko E. A., Vaughan D. E. (2014). Role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in senescence and aging. Semin. Thrombosis Hemostasis 40 645–651. 10.1055/s-0034-1387883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erren T. C., Reiter R. J. (2009). Defining chronodisruption. J. Pineal Res. 46 245–247. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erren T. C., Reiter R. J. (2013). Revisiting chronodisruption: when the physiological nexus between internal and external times splits in humans. Naturwissenschaften 100 291–298. 10.1007/s00114-013-1026-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble K. L., Berry R., Frank S. J., Young M. E. (2014). Circadian clock control of endocrine factors. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10 466–475. 10.1038/nrendo.2014.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godier A., Hunt B. J. (2013). Plasminogen receptors and their role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory, autoimmune and malignant disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 11 26–34. 10.1111/jth.12064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek D. A., Rosenstein R. E. (2010). Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol. Rev. 90 1063–1102. 10.1152/physrev.00009.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumond F., Dardente H., Giguère V., Cermakian N. (2005). Differential control of Bmal1 circadian transcription by REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors. J. Biol. Rhythms 20 391–403. 10.1177/0748730405277232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haus E., Smolensky M. (2006). Biological clocks and shift work: circadian dysregulation and potential long-term effects. Cancer Causes Control 17 489–500. 10.1007/s10552-005-9015-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmeryckx B., Frederix L., Lijnen H. R. (2019). Deficiency of Bmal1 disrupts the diurnal rhythm of haemostasis. Exp. Gerontol. 118 1–8. 10.1016/J.EXGER.2018.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmeryckx B., Van Hove C. E., Fransen P., Emmerechts J., Kauskot A., Bult H., et al. (2011). Progression of the prothrombotic state in aging bmal1-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31 2552–2559. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma S. (2018). The mammalian circadian system: a hierarchical multi-oscillator structure for generating circadian rhythm. J. Physiol. Sci. 68 207–219. 10.1007/s12576-018-0597-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten A. M. (2009). Retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs): critical roles in development, immunity, circadian rhythm, and cellular metabolism. Nucl. Receptor Signal. 7:e003. 10.1621/nrs.07003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Liu H., Wang S., Wang J., Tang Y., He Z., et al. (2018). Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput accelerates atherosclerotic plaque formation by upregulating plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 50 869–879. 10.1093/abbs/gmy087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung R. G., Simard T., Labinaz A., Ramirez F. D., Di Santo P., Motazedian P., et al. (2018). Role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in coronary pathophysiology. Thrombosis Res. 164 54–62. 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.02.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leebeek F. W. G., Rijken D. C. (2015). The fibrinolytic status in liver diseases. Semin. Thrombosis Hemostasis 41 474–480. 10.1055/s-0035-1550437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. C., Tran H. G., Zhang E. E., Priest A. A., Welsh D. K. (2008). Transcriptional regulation of intracellular circadian rhythms. PLoS Genet. 4:1000023. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Legarrea P., Mansego M. L., Zulet M. A., Martinez J. A. (2013). SERPINE1, PAI-1 protein coding gene, methylation levels and epigenetic relationships with adiposity changes in obese subjects with metabolic syndrome features under dietary restriction. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 53 139–144. 10.3164/jcbn.13-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maemura K., de la Monte S. M., Chin M. T., Layne M. D., Hsieh C. M., Yet S. F., et al. (2000). CLIF, a novel cycle-like factor, regulates the circadian oscillation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275 36847–36851. 10.1074/jbc.C000629200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man K., Loudon A., Chawla A. (2016). Immunity around the clock. Science 354 999–1003. 10.1126/science.aah4966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri S., Rigor P., Cervantes M., Ceglia N., Sebastian C., Xiao C., et al. (2014). Partitioning circadian transcription by SIRT6 leads to segregated control of cellular metabolism. Cell 158 659–672. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavri A., Alessi M. C., Juhan-Vague I. (2004). Hypofibrinolysis in the insulin resistance syndrome: implication in cardiovascular diseases. J. Intern. Med. 255 448–456. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavroudis P. D., DuBois D. C., Almon R. R., Jusko W. J. (2018). Modeling circadian variability of core-clock and clock-controlled genes in four tissues of the rat. PLoS ONE 13:e0197534. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoccoli G., Francavilla M., Pazienza V., Benegiamo G., Piepoli A., Vinciguerra M., et al. (2012a). Differential patterns in the periodicity and dynamics of clock gene expression in mouse liver and stomach. Chronobiol. Int. 29 1300–1311. 10.3109/07420528.2012.728662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoccoli G., Pazienza V., Vinciguerra M. (2012b). Clock genes and clock-controlled genes in the regulation of metabolic rhythms. Chronobiol. Int. 29 227–251. 10.3109/07420528.2012.658127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medcalf R. L. (2007). Fibrinolysis, inflammation, and regulation of the plasminogen activating system. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5(Suppl. 1), 132–142. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohawk J. A., Green C. B., Takahashi J. S. (2013). Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammal. 35 445–462. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128.CENTRAL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C. J., Purvis T. E., Hu K., Scheer F. A. J. L. (2016). Circadian misalignment increases cardiovascular disease risk factors in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 E1402–E1411. 10.1073/pnas.1516953113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura N., Oishi K., Fukushima N., Kasamatsu M., Atsumi G. I., Ishida N., et al. (2006). Circadian clock molecules CLOCK and CRYs modulate fibrinolytic activity by regulating the PAI-1 gene expression. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4 2478–2485. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura N., Oishi K., Sakata T., Kadota K., Kasamatsu M., Fukushima N., et al. (2007). Circadian variations in coagulation and fibrinolytic factors among four different strains of mice. Chronobiol. Int. 24 651–669. 10.1080/07420520701534673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K. (2009). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and the circadian clock in metabolic disorders. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 31 208–219. 10.1080/10641960902822468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Miyazaki K., Uchida D., Ohkura N., Wakabayashi M., Doi R., et al. (2009). PERIOD2 is a circadian negative regulator of PAI-1 gene expression in mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 46 545–552. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Ohkura N. (2013). Chronic circadian clock disruption induces expression of the cardiovascular risk factor plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in mice. Blood Coagulat. Fibrinolysis 24 106–108. 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835bfdf3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Shirai H., Ishida N. (2007). Identification of the circadian clock-regulated E-box element in the mouse plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5 428–431. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partch C. L., Green C. B., Takahashi J. S. (2014). Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 24 90–99. 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov M., Ćelap I. (2019). Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in acute coronary syndromes. Clin. Chim. Acta 491 52–58. 10.1016/J.CCA.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietroiusti A., Neri A., Somma G., Coppeta L., Iavicoli I., Bergamaschi A., et al. (2010). Incidence of metabolic syndrome among night-shift healthcare workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 67 54–57. 10.1136/oem.2009.046797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plano S. A., Casiraghi L. P., Moro P. G., Paladino N., Golombek D. A., Chiesa J. J. (2017). Circadian and metabolic effects of light: implications in weight homeostasis and health. Front. Neurol. 8:558. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett D., Reddy A. B. (2015). Circadian clocks in the hematologic system. J. Biol. Rhythms 20 1–15. 10.1177/0748730415592729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke H., Asher G. (2016). Circadian clock control of liver metabolic functions. Gastroenterology 150 574–580. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J., Gumz M. L. (2013). Mechanism of the circadian clock in physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 304 R1053–R1064. 10.1152/ajpregu.00066.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T., Kantermann T., Juda M., Vetter C., Allebrandt K. V. (2013). Light and the Human Circadian Clock. Berlin: Springer, 311–331. 10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer F. A. J. L., Hilton M. F., Mantzoros C. S., Shea S. A. (2009). Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 4453–4458. 10.1073/pnas.0808180106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer F. A. J. L., Michelson A. D., Frelinger A. L., Evoniuk H., Kelly E. E., et al. (2011). The human endogenous circadian system causes greatest platelet activation during the biological morning independent of behaviors. PLoS ONE 6:e24549. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer F. A. J. L., Shea S. A. (2014). Human circadian system causes a morning peak in prothrombotic plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) independent of the sleep/wake cycle. Blood 123 590–593. 10.1182/blood-2013-07-517060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiermann C., Gibbs J., Ince L., Loudon A. (2018). Clocking in to immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18 423–437. 10.1038/s41577-018-0008-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibler U., Gotic I., Saini C., Gos P., Curie T., Emmenegger Y., et al. (2015). Clock-talk: interactions between central and peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals. Cold. Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 80 223–232. 10.1101/sqb.2015.80.027490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhard J. A., Smith L. H., Painter C. A., Eren M., Johnson C. H., Vaughan D. E. (2003). Regulation of the PAI-1 promoter by circadian clock components: differential activation by BMAL1 and BMAL2. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 35 473–481. 10.1016/S0022-2828(03)00051-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimba S., Ogawa T., Hitosugi S., Ichihashi Y., Nakadaira Y., Kobayashi M., et al. (2011). Deficient of a clock gene, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), induces dyslipidemia and ectopic fat formation. PLoS ONE 6:e25231. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver A. C., Arjona A., Hughes M. E., Nitabach M. N., Fikrig E. (2012). Circadian expression of clock genes in mouse macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells. Brain Behav. Immun. 26 407–413. 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somanath P. R., Podrez E. A., Chen J., Ma Y., Marchant K., Antoch M., et al. (2011). Deficiency in core circadian protein Bmal1 is associated with a prothrombotic and vascular phenotype. J. Cell. Physiol. 226 132–140. 10.1002/jcp.22314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens R. G., Hansen J., Costa G., Haus E., Kauppinen T., Aronson K. J., et al. (2011). Considerations of circadian impact for defining “shift work” in cancer studies: IARC Working Group Report. Occup. Environ. Med. 68 154–162. 10.1136/oem.2009.053512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsen P., Hinrichs G. R., Zachar R., Ydegaard R., Jensen B. L. (2017). Physiology and pathophysiology of the plasminogen system in the kidney. Pflugers Archiv. Eur. J. Physiol. 469 1415–1423. 10.1007/s00424-017-2014-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara Y., Shibata S. (2016). Circadian rhythms of liver physiology and disease: experimental and clinical evidence. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13 217–226. 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi J. S. (2016). “Molecular architecture of the circadian clock in mammals,” in A Time for Metabolism and Hormones [Internet], eds Sassone-Corsi P., Christen Y. (Berlin: Springer; ). Availabe online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28892344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y., Jothi R., Birault V., Jetten A. M. (2012). RORc directly regulates thvaughane circadian expression of clock genes and downstream targets in vivo. 2:101185. 10.1093/nar/gks630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofler G. H., Massaro J., O’Donnell C. J., Wilson P. W. F., Vasan R. S., Sutherland P. A., et al. (2016). Plasminogen activator inhibitor and the risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Thrombosis Res. 140 30–35. 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott A. J., Menet J. S. (2018). Regulation of circadian clock transcriptional output by CLOCK:BMAL1. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007156. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H. R., Hayashi S., Chen W., Sano M., Machida M., Shigeyoshi Y., et al. (2005). System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks. Nat. Genet. 37 187–192. 10.1038/ng1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan D. E., Rai R., Khan S. S., Eren M., Ghosh A. K. (2017). PAI-1 is a marker and a mediator of senescence. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37:1446. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y. Z., Gao P., Zhou S., Zhang Z. Q., Hao D. L., Lian L. S., et al. (2014). SIRT1-mediated epigenetic downregulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 prevents vascular endothelial replicative senescence. Aging Cell 13 890–899. 10.1111/acel.12247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yin L., Lazar M. A. (2006). The orphan nuclear receptor Rev-erb? regulates circadian expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor type. J. Biol. Chem. 281 33842–33848. 10.1074/jbc.M607873200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgate E. J., Cheng Y., Reilly D. F., Price T. S., Walisser J. A., Bradfield C. A., et al. (2008). Genetic components of the circadian clock regulate thrombogenesis in vivo. Circulation 117 2087–2095. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Takeshita K., Saito H. (2014). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in aging. Semin. Thrombosis Hemostasis 40 652–659. 10.1055/s-0034-1384635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwighaft Z., Reinke H., Asher G. (2016). The liver in the eyes of a chronobiologist. J. Biol. Rhythms 31 115–124. 10.1177/0748730416633552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]