Abstract

Fusarium oxysporum is the most economically important and commonly encountered species of Fusarium. This soil-borne fungus is known to harbour both pathogenic (plant, animal and human) and non-pathogenic strains. However, in its current concept F. oxysporum is a species complex consisting of numerous cryptic species. Identification and naming these cryptic species is complicated by multiple subspecific classification systems and the lack of living ex-type material to serve as basic reference point for phylogenetic inference. Therefore, to advance and stabilise the taxonomic position of F. oxysporum as a species and allow naming of the multiple cryptic species recognised in this species complex, an epitype is designated for F. oxysporum. Using multi-locus phylogenetic inference and subtle morphological differences with the newly established epitype of F. oxysporum as reference point, 15 cryptic taxa are resolved in this study and described as species.

Keywords: cryptic species, diversity, human and plant pathogens, species complex, subspecific classification

INTRODUCTION

Fusarium oxysporum is the most economically important and commonly encountered species of Fusarium. This soil-borne asexual fungus is known to harbour both pathogenic (plant, animal and human) and non-pathogenic strains (Leslie & Summerell 2006) and is also ranked fifth on a list of top 10 fungal pathogens based on scientific and economic importance (Dean et al. 2012, Geiser et al. 2013). Historically, F. oxysporum has been defined by the asexual phenotype as no sexual morph has yet been discovered, even though several studies have indicated the possible presence of a cryptic sexual cycle (Arie et al. 2000, Yun et al. 2000, Aoki et al. 2014, Gordon 2017). This is further supported by phylogenetic studies that place F. oxysporum within the Gibberella Clade (Baayen et al. 2000, O’Donnell et al. 2009, 2013). These studies also showed that F. oxysporum displays a complicated phylogenetic substructure, indicative of multiple cryptic species within F. oxysporum (Gordon & Martyn 1997, Laurence et al. 2014). As with other Fusarium species complexes, the F. oxysporum species complex (FOSC) has suffered from multiple taxonomic/classification systems applied in the past.

Diederich F.L. von Schlechtendal first introduced F. oxysporum in 1824, isolated from a rotten potato tuber (Solanum tuberosum) collected in Berlin, Germany. Wollenweber (1913) placed F. oxysporum within the section Elegans along with eight other Fusarium species and numerous varieties and forms based on similarity of the micro- and macroconidial morphology and dimensions. Snyder & Hansen (1940) later consolidated and reduced all species within the section Elegans into F. oxysporum and designated 25 special forms (formae speciales) within this species. These special forms were further expanded on by Gordon (1965) to 66, most of which are still used in literature today.

The use of special forms or formae speciales as subspecific rank in F. oxysporum classification has become common practice due to the broad morphological delineation of this species (Leslie & Summerell 2006). This informal subspecific rank is defined based on the plant pathogenicity of the particular F. oxysporum strain and excludes both clinical and non-pathogenic strains (Armstrong & Armstrong 1981, Gordon & Martyn 1997, Kistler 1997, Baayen et al. 2000, Leslie & Summerell 2006). Therefore, F. oxysporum strains attacking the same plant host are generally considered to belong to the same special form. Although this homologous trait has led to erroneous assumptions considering a specific special form to be phylogenetically monophyletic, several studies (O’Donnell et al. 1998, 2004, 2009, O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1999, Baayen et al. 2000, Lievens et al. 2009b, Van Dam et al. 2016) have highlighted the para- and polyphyletic relationships within several F. oxysporum special forms, e.g., F. oxysporum f. sp. batatas, F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense and F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum. Additionally, several F. oxysporum special forms are able to infect and cause disease in more than one (sometimes unrelated) plant hosts, whereas others are highly specialised to a specific plant host (Armstrong & Armstrong 1981, Gordon & Martyn 1997, Kistler 1997, Baayen et al. 2000, Leslie & Summerell 2006, Fourie et al. 2011).

Naming F. oxysporum special forms are not subject to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN; McNeill et al. 2012, Thurland et al. 2018), and therefore no diagnosis (in Latin and/or English), nor the deposit of type material in a recognised repository is required. This decision was made due to the difficulty in accepting special forms within the Code, even though these strains are of great importance to plant pathologists and breeders (Deighton et al. 1962, Gordon 1965, Armstrong & Armstrong 1981). Several studies on F. oxysporum indicate that between 70 to over 150 special forms are known in F. oxysporum (Booth 1971, Armstrong & Armstrong 1981, Kistler 1997, Baayen et al. 2000, Leslie & Summerell 2006, Lievens et al. 2008, O’Donnell et al. 2009, Fourie et al. 2011, Laurence et al. 2014, Gordon 2017). At present Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/) lists 124 special forms in F. oxysporum, whereas MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org/) list 127 special forms. Further careful scrutiny of literature revealed that 144 special forms have been named until February 2018 (Table 1). Although the special forms concept of Snyder & Hansen (1940) is still applied today, additional subspecific classification systems for special forms of F. oxysporum have also been introduced, which include haplotypes, races and vegetative compatibility groups (VCGs).

Table 1.

List of known special forms of Fusarium oxysporum.

The haplotype subspecific classification system was introduced by Chang et al. (2006) and later expanded upon by O’Donnell et al. (2008, 2009) to include strains from both the FOSC and Neocosmospora (formerly the F. solani (FSSC) species complex). This classification system is based on unique multilocus genotypes within the species complex, aimed to resolve communication problems among public health and agricultural scientists (O’Donnell et al. 2008). Chang et al. (2006) proposed a standardised haplotype nomenclature system that depict the species complex, species and genotype. O’Donnell et al. (2009) was able to identify 256 unique two-locus haplotypes from 850 isolates representing 68 special forms of F. oxysporum as well as environmental and clinical strains. However, this classification system is not in common use as a reference, and a continuously updated database is required.

One of the most important subspecific ranks applied to special forms of F. oxysporum are physiological pathotypes or races. This classification system is of great importance to plant breeders, especially for resistance breeding. Traditionally, race demarcation is based on cultivar specificity linked to specific resistance genes of the plant host cultivar (Armstrong & Armstrong 1981, Kistler 1997, Baayen et al. 2000, Roebroeck 2000, Fourie et al. 2011, Epstein et al. 2017). However, race designation has been inconsistent in the past (Gerlagh & Blok 1988, Correll 1991, Kistler 1997, Fourie et al. 2011) with several different nomenclatural systems being applied (Gabe 1975, Risser et al. 1976, Armstrong & Armstrong 1981) to further cause confusion (Kistler 1997). With advances in molecular technology, identification of races has been simplified using sequence-characterised amplified region (SCAR) primers (Lievens et al 2008, Epstein et al. 2017, Gilardi et al. 2017). However, time consuming and laborious pathogenicity tests are still needed to identify new emerging races and to test whether newly developed plant cultivars are resistant to known races (Epstein et al. 2017, Gilardi et al. 2017).

The use of vegetative compatibility (also known as heterokaryon compatibility) has formed an integral part of subspecific classification of F. oxysporum special forms and non-pathogenic strains. Formation of a stable heterokaryon between two auxotrophic nutritional mutants is regulated by several vic or het incompatibility loci (Correll 1991, Leslie 1993) indicating that the strains are homogenic at these loci (Correll 1991) and considered to be part of the same VCG. Therefore, classification using vegetative compatibility is based on genetic similarity at specific loci and not pathogenicity, providing a crude marker for population genetic studies (Correll 1991, Gordon & Martyn 1997, Leslie 1993, Leslie & Summerell 2006). Puhalla (1985), utilizing nit mutants, was the first to identify VCGs in F. oxysporum and characterised 16 VCGs in a collection of 21 F. oxysporum strains. The numbering system applied by Puhalla (1985), which is still used today, consists of a three-digit numerical code indicating the special form followed by digit(s) indicating the VCG (Katan 1999, Katan & Di Primo 1999). Conventional VCG characterisation is a relatively objective, time consuming and laborious assay only indicating genetic similarity and not genetic difference (Kistler 1997). Therefore, several PCR-based detection methods have been developed to identify economically important VCGs as diagnostic tool (Fernandez et al. 1998, Pasquali et al. 2004a, c, Lievens et al. 2008), e.g., F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense TR4 VCG01213 (Dita et al. 2010).

Until recently, limited knowledge on the genetic premise for host specificity in F. oxysporum was available (Gordon & Martyn 1997, Kistler 1997, Baayen et al. 2000). However, the discovery of a lineage-specific chromosome (or transposable/effector/accessory chromosome) in F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici by Ma et al. (2010), in which the host specific virulence genes lie (Van der Does et al. 2008, Takken & Rep 2010, Ma et al. 2013), has provided a new view into the evolution of pathogenicity in F. oxysporum. In vitro transfer of these accessory chromosomes into non-pathogenic F. oxysporum strains has converted the latter strains into host-specific pathogens, providing evidence that host-specific pathogenicity could be acquired through horizontal transfer of accessory chromosomes (Takken & Rep 2010, Ma et al. 2010, 2013, Van Dam et al. 2016, Van Dam & Rep 2017). Therefore, the special form name can be linked to the accessory chromosome whereas race demarcation can be linked to the specific virulence genes carried on these accessory chromosomes.

The genetic and functional mechanisms of the infection process in plants of various special forms of F. oxysporum has been well documented (Di Pietro et al. 2003, Ma et al. 2013, Upasani et al. 2016, Gordon 2017). However, these same mechanisms are still poorly understood in human and animal infections (O’Donnell et al. 2004, Guarro 2013, Van Diepeningen et al. 2015). Fusarium oxysporum has been linked to fungal keratitis (Hemo et al. 1989, Chang et al. 2006) and dermatitis (Guarro & Gene 1995, Romano et al. 1998, Ninet et al. 2005, Cutuli et al. 2015, Van Diepeningen et al. 2015), and has been isolated from contaminated hospital water systems (Steinberg et al. 2015, Edel-Hermann et al. 2016) and medical equipment (Barton et al. 2016, Carlesse et al. 2017) posing a serious threat to immunocompromised patients. Several recent reports also indicate that F. oxysporum is able to infect immunocompetent patients (Jiang et al. 2016, Khetan et al. 2018). In general, fusariosis is difficult to treat as Fusarium species display a remarkable resistance to antifungal agents (Guarro 2013, Al-Hatmi et al. 2018). However, some antimycotics are known to be effective against F. oxysporum related fusariosis (Al-Hatmi et al. 2018). Recently, both mycotoxins beauvericin and fusaric acid, produced by F. oxysporum strains that can infect tomato, have been shown to be important virulence determinants to infect immunosuppressed mice (López-Berges et al. 2013, López-Díaz et al. 2018).

Strains of F. oxysporum are known to produce a cocktail of polyketide secondary metabolites, some with unknown function and toxicities (Marasas et al. 1984, Mirocha et al. 1989, Bell et al. 2003, Desjardins 2006, Manici et al. 2017). Some of the better-known toxins produced by F. oxysporum include beauvericin (Marasas et al. 1984, Logrieco et al. 1998, López-Berges et al. 2013), fusaric acid (Marasas et al. 1984, López-Díaz et al. 2018) and fumonisins (Rheeder et al. 2002) to name a few. Mycotoxicological studies on F. oxysporum has thus far only focused on a strain to strain basis and therefore no link has yet been established between special form and/or race and mycotoxin production capabilities.

In light of the complicated and sometimes confusing classification systems applied to F. oxysporum taxonomy and nomenclature, the question has risen whether F. oxysporum truly represent a species (Kistler 1997). Given that F. oxysporum is a common, widespread, soil-borne fungus, with a global distribution and high economic importance, this question requires urgent attention. Therefore, to advance and stabilize the taxonomic and nomenclatural position of F. oxysporum and allow naming of the multiple cryptic species recognised in this species complex, Fusarium isolates were collected from the type locality in Berlin, Germany, and the type substrate, Solanum tuberosum. Using molecular phylogenetic and morphological tools, an epitype is designated for F. oxysporum in the present study based on these collections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates

Tubers of S. tuberosum (potato), displaying symptoms of dry rot, were collected from several vegetable gardens in Berlin, Germany. Potato tubers were placed individually in paper bags, stored at 4 °C until transported to the laboratory for further processing. After surface-sterilisation of the potato tubers using a 10 % (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution, pieces of symptomatic tissue were removed from the leading edges of the rot lesions and plated onto 2 % (w/v) potato dextrose agar (PDA) amended with 100 μg/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and peptone pentachloronitrobenzene agar (PCNB; Nash & Snyder 1962) and incubated at 25 °C in the dark. Axenic cultures were prepared on PDA from characteristic Fusarium colonies. Additional strains, previously identified as F. oxysporum, were obtained from the culture collection (CBS) of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (WFBI), Utrecht, the Netherlands, and the working collection of Pedro W. Crous (CPC) housed at WFBI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of Fusarium strains included in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Culture accession1 | Host/substrate | Special form | Origin | GenBank accession | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmdA | IGS | rpb2 | tef1 | tub2 | |||||

| Fusarium callistephi | CBS 187.53T | Callistephus chinensis | callistephi | The Netherlands | MH484693 | MH484784 | MH484875 | MH484966 | MH485057 |

| CBS 115423 | Agathosma betulina | South Africa | MH484723 | MH484814 | MH484905 | MH484996 | MH485087 | ||

| F. carminascens | CBS 144739 = CPC 25792 | Zea mays | South Africa | MH484752 | MH484843 | MH484934 | MH485025 | MH485116 | |

| CBS 144740 = CPC 25793 | Z. mays | South Africa | MH484753 | MH484844 | MH484935 | MH485026 | MH485117 | ||

| CBS 144741 = CPC 25795 | Z. mays | South Africa | MH484754 | MH484845 | MH484936 | MH485027 | MH485118 | ||

| CBS 144738 = CPC 25800T | Z. mays | South Africa | MH484755 | MH484846 | MH484937 | MH485028 | MH485119 | ||

| F. contaminatum | CBS 111552 | Pasteurized fruit juice | The Netherlands | MH484718 | MH484809 | MH484900 | MH484991 | MH485082 | |

| CBS 114899T | Pasteurized chocolate milk | Germany | MH484719 | MH484810 | MH484901 | MH484992 | MH485083 | ||

| CBS 117461 | Tetra pack with milky nutrition | The Netherlands | MH484729 | MH484820 | MH484911 | MH485002 | MH485093 | ||

| F. cugenangense | CBS 620.72 = DSM 11271 = NRRL 36520 | Crocus sp. | gladioli | Germany | MH484697 | MH484788 | MH484879 | MH484970 | MH485061 |

| CBS 130304 = BBA 69050 = NRRL 25433 | Gossypium barbadense | vasinfectum | China | MH484739 | MH484830 | MH484921 | MH485012 | MH485103 | |

| CBS 130308 = ATCC 26225 = NRRL 25387 | Human toe nail | New Zealand | MH484738 | MH484829 | MH484920 | MH485011 | MH485102 | ||

| CBS 131393 | Vicia faba | Australia | MH484746 | MH484837 | MH484928 | MH485019 | MH485110 | ||

| F. curvatum | CBS 247.61 = BBA 8398 = DSM 62308 = NRRL 22545 | Matthiola incana | matthiolae | Germany | MH484694 | MH484785 | MH484876 | MH484967 | MH485058 |

| CBS 238.94 = NRRL 26422 = PD 94/184T | Beaucarnia sp. | meniscoideum | The Netherlands | MH484711 | MH484802 | MH484893 | MH484984 | MH485075 | |

| CBS 141.95 = NRRL 36251 = PD 94/1518 | Hedera helix | The Netherlands | MH484712 | MH484803 | MH484894 | MH484985 | MH485076 | ||

| F. duoseptatum | CBS 102026 = NRRL 36115 | Musa sapientum cv. Pisang ambon | cubense | Malaysia | MH484714 | MH484805 | MH484896 | MH484987 | MH485078 |

| F. elaeidis | CBS 217.49 = NRRL 36358 | Elaeis sp. | elaeidis | Zaire | MH484688 | MH484779 | MH484870 | MH484961 | MH485052 |

| CBS 218.49 = NRRL 36359 | Elaeis sp. | elaeidis | Zaire | MH484689 | MH484780 | MH484871 | MH484962 | MH485053 | |

| CBS 255.52 = NRRL 36386 | Elaeis guineensis | elaeidis | Unknown | MH484692 | MH484783 | MH484874 | MH484965 | MH485056 | |

| F. fabacearum | CBS 144742 = CPC 25801 | Z. mays | South Africa | MH484756 | MH484847 | MH484938 | MH485029 | MH485120 | |

| CBS 144743 = CPC 25802T | Glycine max | South Africa | MH484757 | MH484848 | MH484939 | MH485030 | MH485121 | ||

| CBS 144744 = CPC 25803 | G. max | South Africa | MH484758 | MH484849 | MH484940 | MH485031 | MH485122 | ||

| F. foetens | CBS 120665 | Nicotiana tabacum | Iran | MH484736 | MH484827 | MH484918 | MH485009 | MH485100 | |

| F. glycines | CBS 176.33 = NRRL 36286 | Linum usitatissium | lini | Unknown | MH484686 | MH484777 | MH484868 | MH484959 | MH485050 |

| CBS 214.49 = NRRL 36356 | Unknown | Argentina | MH484687 | MH484778 | MH484869 | MH484960 | MH485051 | ||

| CBS 200.89 | Ocimum basilicum | basilici | Italy | MH484706 | MH484797 | MH484888 | MH484979 | MH485070 | |

| CBS 144745 = CPC 25804 | G. max | South Africa | MH484759 | MH484850 | MH484941 | MH485032 | MH485123 | ||

| CBS 144746 = CPC 25808T | G. max | South Africa | MH484760 | MH484851 | MH484942 | MH485033 | MH485124 | ||

| F. gossypinum | CBS 116611 | Gossypium hirsutum | vasinfectum | Ivory Coast | MH484725 | MH484816 | MH484907 | MH484998 | MH485089 |

| CBS 116612 | G. hirsutum | vasinfectum | Ivory Coast | MH484726 | MH484817 | MH484908 | MH484999 | MH485090 | |

| CBS 116613T | G. hirsutum | vasinfectum | Ivory Coast | MH484727 | MH484818 | MH484909 | MH485000 | MH485091 | |

| F. hoodiae | CBS 132474T | Hoodia gordonii | hoodiae | South Africa | MH484747 | MH484838 | MH484929 | MH485020 | MH485111 |

| CBS 132476 | H. gordonii | hoodiae | South Africa | MH484748 | MH484839 | MH484930 | MH485021 | MH485112 | |

| CBS 132477 | H. gordonii | hoodiae | South Africa | MH484749 | MH484840 | MH484931 | MH485022 | MH485113 | |

| F. languescens | CBS 645.78 = NRRL 36531T | Solanum lycopersicum | lycopersici | Morocco | MH484698 | MH484789 | MH484880 | MH484971 | MH485062 |

| CBS 646.78 = NRRL 36532 | S. lycopersicum | lycopersici | Morocco | MH484699 | MH484790 | MH484881 | MH484972 | MH485063 | |

| CBS 413.90 = ATCC 66046 = NRRL 36465 | S. lycopersicum | lycopersici | Israel | MH484708 | MH484799 | MH484890 | MH484981 | MH485072 | |

| CBS 300.91 = NRRL 36416 | S. lycopersicum | lycopersici | The Netherlands | MH484709 | MH484800 | MH484891 | MH484982 | MH485073 | |

| CBS 302.91 = NRRL 36419 | S. lycopersicum | lycopersici | The Netherlands | MH484710 | MH484801 | MH484892 | MH484983 | MH485074 | |

| CBS 872.95 = NRRL 36570 | S. lycopersicum | radicis-lycopersici | Unknown | MH484713 | MH484804 | MH484895 | MH484986 | MH485077 | |

| CBS 119796 = MRC 8437 | Z. mays | South Africa | MH484735 | MH484826 | MH484917 | MH485008 | MH485099 | ||

| F. libertatis | CBS 144748 = CPC 25782 | Aspalathus sp. | South Africa | MH484750 | MH484841 | MH484932 | MH485023 | MH485114 | |

| CBS 144747 = CPC 25788 | Aspalathus sp. | South Africa | MH484751 | MH484842 | MH484933 | MH485024 | MH485115 | ||

| CBS 144749 = CPC 28465T | Rock surface | South Africa | MH484762 | MH484853 | MH484944 | MH485035 | MH485126 | ||

| F. nirenbergiae | CBS 129.24 | Secale cereale | Unknown | MH484682 | MH484773 | MH484864 | MH484955 | MH485046 | |

| CBS 149.25 = NRRL 36261 | Musa sp. | cubense | Unknown | MH484683 | MH484774 | MH484865 | MH484956 | MH485047 | |

| CBS 181.32 = NRRL 36303 | S. tuberosum | USA | MH484685 | MH484776 | MH484867 | MH484958 | MH485049 | ||

| CBS 758.68 = NRRL 36546 | S. lycopersicum | lycopersici | The Netherlands | MH484695 | MH484786 | MH484877 | MH484968 | MH485059 | |

| CBS 744.79 = BBA 62355 = NRRL 22549 | Passiflora edulis | passiflorae | Brazil | MH484700 | MH484791 | MH484882 | MH484973 | MH485064 | |

| CBS 127.81 = BBA 63924 = NRRL 36229 | Chrysanthemum sp. | chrysanthemi | USA | MH484701 | MH484792 | MH484883 | MH484974 | MH485065 | |

| CBS 129.81 = BBA 63926 = NRRL 22539 | Chrysanthemum sp. | chrysanthemi | USA | MH484703 | MH484794 | MH484885 | MH484976 | MH485067 | |

| CBS 196.87 = NRRL 26219 | Bouvardia longiflora | bouvardiae | Italy | MH484704 | MH484795 | MH484886 | MH484977 | MH485068 | |

| CBS 840.88T | Dianthus caryophyllus | dianthi | The Netherlands | MH484705 | MH484796 | MH484887 | MH484978 | MH485069 | |

| CBS 115416 = CPC 5307 | Agathosma betulina | South Africa | MH484720 | MH484811 | MH484902 | MH484993 | MH485084 | ||

| CBS 115417 = CPC 5306 | A. betulina | South Africa | MH484721 | MH484812 | MH484903 | MH484994 | MH485085 | ||

| CBS 115419 = CPC 5308 | A. betulina | South Africa | MH484722 | MH484813 | MH484904 | MH484995 | MH485086 | ||

| CBS 115424 = CPC 5312 | A. betulina | South Africa | MH484724 | MH484815 | MH484906 | MH484997 | MH485088 | ||

| CBS 123062 = GJS 91-17 | Tulip roots | USA | MH484737 | MH484828 | MH484919 | MH485010 | MH485101 | ||

| CBS 130300 = NRRL 26368 | Amputated human toe | USA | MH484743 | MH484834 | MH484925 | MH485016 | MH485107 | ||

| CBS 130301 = NRRL 26374 | Human leg ulcer | USA | MH484744 | MH484835 | MH484926 | MH485017 | MH485108 | ||

| CBS 130303 | S. lycopersicum | radicis-lycopersici | USA | MH484741 | MH484832 | MH484923 | MH485014 | MH485105 | |

| CPC 30807 | South Africa | MH484768 | MH484859 | MH484950 | MH485041 | MH485132 | |||

| F. odoratissimum | CBS 794.70 = BBA 11103 = NRRL 22550 | Albizzia julibrissin | perniciosum | Iran | MH484696 | MH484787 | MH484878 | MH484969 | MH485060 |

| CBS 102030 | M. sapientum cv. Pisang mas | cubense | Malaysia | MH484716 | MH484807 | MH484898 | MH484989 | MH485080 | |

| CBS 130310 = NRRL 25603 | Musa sp. | cubense | Australia | MH484740 | MH484831 | MH484922 | MH485013 | MH485104 | |

| F. oxysporum | CBS 221.49 = IHEM 4508 = NRRL 22546 | Camellia sinensis | medicaginis | South East Asia | MH484690 | MH484781 | MH484872 | MH484963 | MH485054 |

| CBS 144134ET | S. tuberosum | Germany | MH484771 | MH484862 | MH484953 | MH485044 | MH485135 | ||

| CBS 144135 | S. tuberosum | Germany | MH484772 | MH484863 | MH484954 | MH485045 | MH485136 | ||

| CPC 25822 | Protea sp. | South Africa | MH484761 | MH484852 | MH484943 | MH485034 | MH485125 | ||

| F. pharetrum | CBS 144750 = CPC 30822 | Aliodendron dichotomum | South Africa | MH484769 | MH484860 | MH484951 | MH485042 | MH485133 | |

| CBS 144751 = CPC 30824T | A. dichotomum | South Africa | MH484770 | MH484861 | MH484952 | MH485043 | MH485134 | ||

| F. trachichlamydosporum | CBS 102028 = NRRL 36117 | M. sapientum cv. Pisang awak legor | cubense | Malaysia | MH484715 | MH484806 | MH484897 | MH484988 | MH485079 |

| F. triseptatum | CBS 258.50 = NRRL 36389T | Ipomoea batatas | batatas | USA | MH484691 | MH484782 | MH484873 | MH484964 | MH485055 |

| CBS 116619 | G. hirsutum | vasinfectum | Ivory Coast | MH484728 | MH484819 | MH484910 | MH485001 | MH485092 | |

| CBS 119665 | Sago starch | Papua New Guinea | MH484734 | MH484825 | MH484916 | MH485007 | MH485098 | ||

| CBS 130302 = NRRL 26360 = FRC 755 | Human eye | USA | MH484742 | MH484833 | MH484924 | MH485015 | MH485106 | ||

| F. udum | CBS 177.31 | Digitaria eriantha | South Africa | MH484684 | MH484775 | MH484866 | MH484957 | MH485048 | |

| F. veterinarium | CBS 109898 = NRRL 36153T | Shark peritoneum | The Netherlands | MH484717 | MH484808 | MH484899 | MH484990 | MH485081 | |

| CBS 117787 | Swab sample near filling apparatus | The Netherlands | MH484730 | MH484821 | MH484912 | MH485003 | MH485094 | ||

| CBS 117790 | Swab sample near filling apparatus | The Netherlands | MH484731 | MH484822 | MH484913 | MH485004 | MH485095 | ||

| CBS 117791 | Pasteurized milk-based product | The Netherlands | MH484732 | MH484823 | MH484914 | MH485005 | MH485096 | ||

| CBS 117792 | Pasteurized milk-based product | The Netherlands | MH484733 | MH484824 | MH484915 | MH485006 | MH485097 | ||

| NRRL 54984 | Mouse mucosa | USA | MH484763 | MH484854 | MH484945 | MH485036 | MH485127 | ||

| NRRL 54996 | Little blue penguin foot | USA | MH484764 | MH484855 | MH484946 | MH485037 | MH485128 | ||

| NRRL 62542 | Unknown animal faeces | USA | MH484765 | MH484856 | MH484947 | MH485038 | MH485129 | ||

| NRRL 62545 | Endoscope of veterinary clinic | USA | MH484766 | MH484857 | MH484948 | MH485039 | MH485130 | ||

| NRRL 62547 | Canine stomach | USA | MH484767 | MH484858 | MH484949 | MH485040 | MH485131 | ||

| Fusarium sp. | CBS 128.81 = BBA 63925 = NRRL 36233 | Chrysanthemum sp. | chrysanthemi | USA | MH484702 | MH484793 | MH484884 | MH484975 | MH485066 |

| CBS 680.89 = NRRL 26221 | Cucumis sativus | cucurbitacearum | The Netherlands | MH484707 | MH484798 | MH484889 | MH484980 | MH485071 | |

| CBS 130323 | Human nail | Australia | MH484745 | MH484836 | MH484927 | MH485018 | MH485109 | ||

1ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, USA; BBA: Biologische Bundesanstalt für Land-und Forstwirtschaft, Berlin-Dahlem, Germany; CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiverity Institute (WIFB), Utrecht, The Netherlands; CPC: Collection of P.W. Crous; DSM: Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany; FRC: Fusarium Research Center, Penn State University, Pennsylvania; GJS: Collection of Gary J. Samuels; IHEM: Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology-Mycology Laboratory, Brussels, Belgium; MRC: National Research Institute for Nutritional Diseases, Tygerberg, South Africa; NRRL: Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, USA; PD: Collection of the Dutch National Plant Protection Organization, Wageningen, The Netherlands. T Ex-type culture; ETEpitype.

DNA isolation, PCR and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from isolates grown for 7 d on PDA at 24 °C using a 12/12 h photoperiod using the Wizard® Genomic DNA purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Partial gene sequences were determined for the β-tubulin (tub2), calmodulin (cmdA), the intergenic spacer region of the rDNA (IGS), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2) and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), using PCR protocols described elsewhere (O’Donnell et al. 1998, 2007, 2009, 2010, Lombard et al. 2015). Primer pairs T1/CYLTUB1R (O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1997, Crous et al. 2004) for tub2, Cal228F/CAL2Rd (Carbone & Kohn 1999, Groenewald et al. 2013) for cmdA, iNL11/iCNS1 and the internal sequencing primers NLa/CNSa (O’Donnell et al. 2009) for IGS, 5f2/7cr (Liu et al. 1999, Sung et al. 2007) for rpb2, and EF1/EF2 (O’Donnell et al. 1998) for tef1, were used for amplifications of the respective gene regions. Integrity of the sequences was ensured by sequencing the amplicons in both directions using the same primer pairs as were used for amplification. Consensus sequences for each locus were assembled in MEGA v. 7 (Kumar et al. 2016), with the exception of the IGS locus, which was assembled in Geneious R11 (Kearse et al. 2012). All sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequences of the individual loci were aligned using MAFFT v. 7.110 (Katoh et al. 2017) and manually corrected where necessary. The individual gene datasets were assessed for incongruency prior to concatenation using a 70 % reciprocal bootstrap criterion (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996). Three independent phylogenetic algorithms, Maximum Parsimony (MP), Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI), were employed for phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted for the individual loci and then as a multilocus sequence dataset that included the cmdA, rpb2, tef1 and tub2 sequences.

For BI and ML, the best evolutionary models for each locus were determined using MrModeltest (Nylander 2004) and incorporated into the analyses. MrBayes v. 3.2.1 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) was used for BI to generate phylogenetic trees under optimal criteria for each locus. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm of four chains was initiated in parallel from a random tree topology with the heating parameter set at 0.3. The MCMC analysis lasted until the average standard deviation of split frequencies was below 0.01 with trees saved every 1000 generations. The first 25 % of saved trees were discarded as the ‘burn-in’ phase and posterior probabilities (PP) were determined from the remaining trees.

The ML analyses were performed using RAxML v. 8.2.9 (randomised accelerated (sic) maximum likelihood for high performance computing; Stamatakis 2014) through the CIPRES website (http://www.phylo.org) to obtain another measure of branch support. The robustness of the analysis was evaluated by bootstrap support (BS) with the number of bootstrap replicates automatically determined by the software. For MP, analyses were done using PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, v. 4.0b10; Swofford 2003) with phylogenetic relationships estimated by heuristic searches with 1 000 random addition sequences. Tree-bisection-reconnection was used, with branch swapping option set on ‘best trees’ only. All characters were weighted equally and alignment gaps treated as fifth state. Measures calculated for parsimony included tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and rescaled consistence index (RC). Bootstrap (BS) analyses (Hillis & Bull 1993) were based on 1 000 replications. Alignments and phylogenetic trees derived from this study were uploaded to TreeBASE (www.treebase.org).

Genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition (GCPSR)

In order to establish the recombination levels between the newly proposed species in this study and their closest phylogenetic relatives, pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) analyses were done on the respective concatenated multilocus datasets (Bruen et al. 2006). The analyses were conducted as described by Quaedvlieg et al. (2014) using SplitsTree v. 4.14.4 (Huson & Bryant 2006). Therefore, a PHI value below 0.05 (ϕW < 0.05) would indicate the presence of significant recombination in the dataset. Split graphs were constructed for visualization of the relationships between closely related species.

Morphological characterisation

All isolates were characterised following the protocols described by Leslie & Summerell (2006) using potato dextrose agar (PDA; recipe in Crous et al. 2009), synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA; Nirenberg 1976) and carnation leaf agar (CLA; Fisher et al. 1982). Colony morphology, pigmentation, odour and growth rates were evaluated on PDA after 3 and 7 d at 24 °C with a 12/12 h cool fluorescent light/dark cycle as described by Sandoval-Denis et al. (2018) and using the colour charts of Rayner (1970). Micromorphological characters were examined using water as mounting medium on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus with Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) optics and a Nikon AZ100 stereomicroscope both fitted with Nikon DS-Ri2 high definition colour digital cameras to photo-document fungal structures. Measurements were taken using the Nikon software NIS-elements D v. 4.50 and the 95 % confidence levels were determined for the conidial measurements with extremes given in parentheses. For all other fungal structures examined, only the extremes are presented. To facilitate the comparison of relevant micro- and macroconidial features, composite photo plates were assembled from separate photographs using PhotoShop CSS.

RESULTS

Isolates

A total of 23 fusarium-like isolates were obtained from the symptomatic tissues of the potato tubers. Of these, six isolates displayed typical F. oxysporum-like phenotypes, of which two (CBS 144134 and CBS 144135) were selected for further study.

Phylogenetic analyses

Approximately 500–650 bases were determined for cmdA, tef1 and tub2, 880 bases for rpb2 and 2 650 bases for IGS. Sequence comparisons of the IGS, rpb2 and tef1 gene regions generated in this study, against those in the Fusarium-ID (http://isolate.fusariumdb.org/blast.php) and Fusarium-MLST (http://www.westerdijkinstitute.nl/fusarium/) databases revealed that all isolates included in this study belonged to the FOSC. The congruency analysis revealed no conflict between the cmdA, rpb2, tef1 and tub2 sequence datasets and were therefore combined. However, the IGS sequence dataset revealed major conflict with several included taxa resolving into single lineages due to the large number of ambiguous regions in this gene region. Therefore, the IGS sequences were excluded from further analyses.

For the BI and ML analyses, a K80 model for cmdA, an HKY+ G+I model for rpb2, an HKY+G for tef1 and SYM+I+G model for tub2 were selected and incorporated into the analyses. The ML tree topology confirmed the tree topologies obtained from the BI and MP analyses, and therefore, only the ML tree is presented.

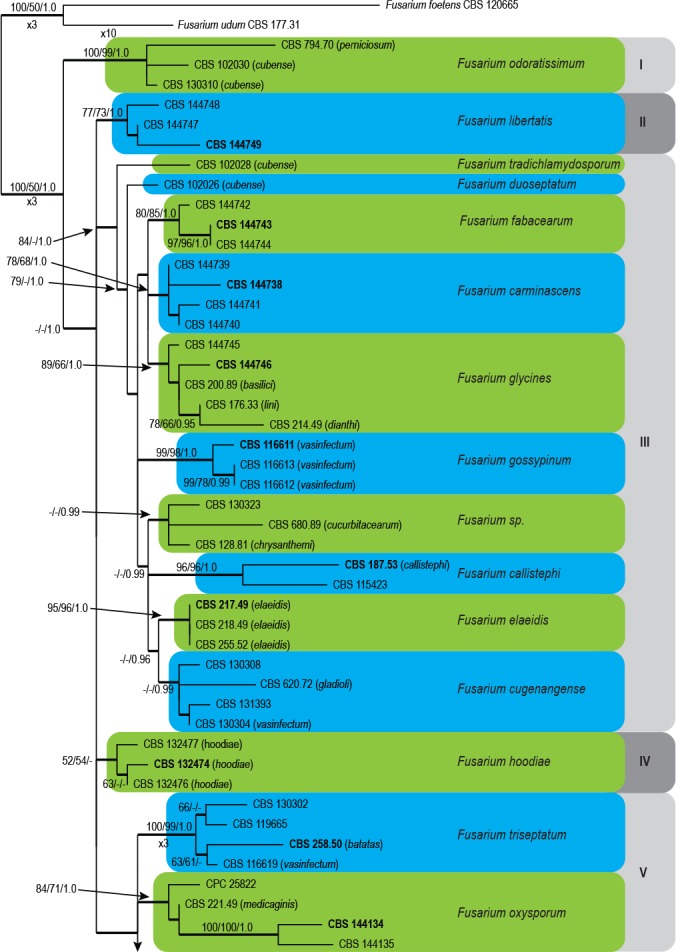

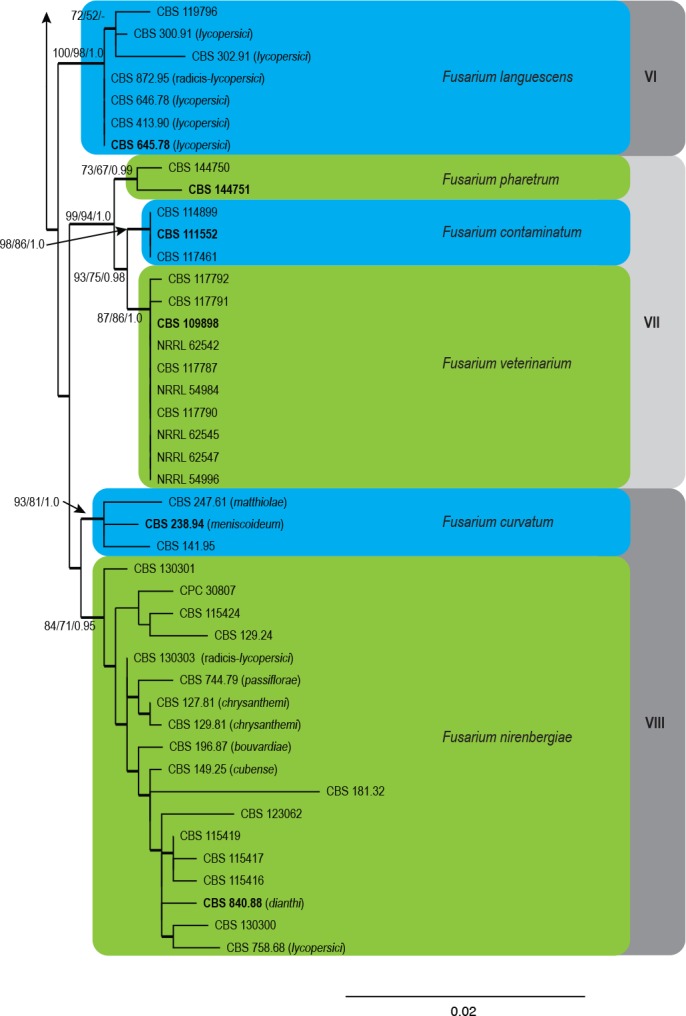

The combined four loci sequence dataset included 89 ingroup taxa with F. foetens (CBS 120665) and F. udum (CBS 177.31) as outgroup taxa. The dataset consisted of 2 679 characters including gaps. Of these characters, 2 291 were constant, 211 parsimony-uninformative and 177 parsimony-informative. The BI lasted for 1.2 M generations, and the consensus tree and posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated from 8 814 trees left after 2 937 were discarded as the ‘burn-in’ phase. The MP analysis yielded 1 000 trees (TL = 574; CI = 0.747; RI = 0.858; RC = 0.641) and a single best ML tree with -InL = 7353.014512 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The ML consensus tree inferred from the combined cmdA, rpb2, tef1 and tub2 sequence alignment. Thickened branches indicate branches present in the ML, MP and Bayesian consensus trees. Support values (ML & MP bootstrap and posterior probability values) are indicated at the branches. The scale bar indicates 0.02 expected changes per site. Clade numbers are provided on the right of the tree and these are used for reference in the treatment of the species. The tree is rooted to F. foetens (CBS 120665) and F. udum (CBS 177.31). Epi- and ex-type strains are indicated in bold.

In the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) the ingroup taxa resolved into eight clades (I–VIII). Of these, Clades I, II, IV and VI represent single well- (ML & MP-BS ≥ 75–95 %; PP ≥ 0.95–0.98) to highly (ML & MP-BS ≥ 96 %; PP ≥ 0.99–1.0) supported clades, whereas Clades III, V, VII and VIII displayed substantial substructure. Clade III included eight well- to highly supported subclades as well as two single lineages. Sequence comparisons of the rpb2 and tef1 sequences with those generated by Maryani et al. (2019) revealed that both single lineages represented F. duoseptatum (CBS 102026) and F. tradichlamydosporum (CBS 102028), respectively. Similarly, the subclade that include isolates CBS 620.72, CBS 130304, CBS 130308 and CBS 131393 represent F. cugenangense. Both Clades V and VIII resolved two subclades in each, and Clade VII included three subclades. The phylogenetic relationships between Clades I–VIII and their underlying subclades are further discussed in the notes in the Taxonomy section.

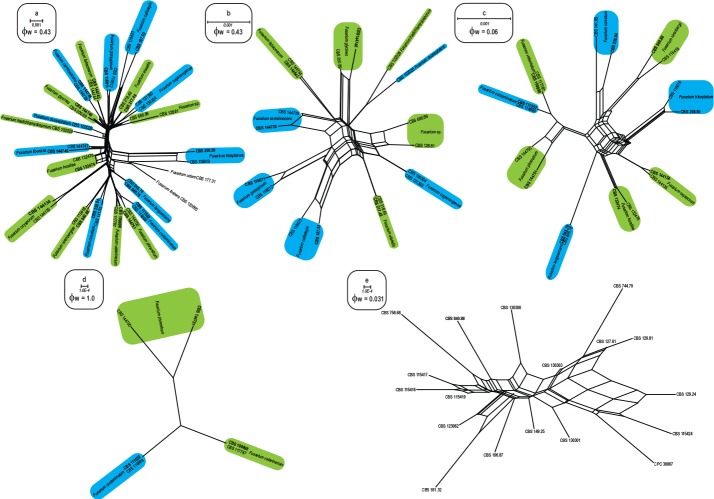

The PHI tests revealed that no evidence of recombination (ϕW = 0.43; Fig. 2a) was detected between each Clade (I–VIII) and their underlining subclades. Similarly, the genealogical exclusivity of the subclades in Clades III (ϕW = 0.43; Fig. 2b) and VII (ϕW = 1.0; Fig. 2d), as well as between Clades IV–VIII (ϕW = 0.06; Fig. 2c) was also confirmed. The basal subclade in Clade VIII (ϕW = 0.031; Fig. 2c), however, showed significant evidence for recombination among all isolates included.

Fig. 2.

Splitgraphs showing the results of the pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) test of newly described taxa using both LogDet transformation and splits decomposition. PHI test results (ϕW) < 0.05 indicate significant recombination within the dataset. a. Representatives of all phylogenetic species resolved in this study; b. phylogenetic species in Clade III; c. phylogenetic species in Clades IV–VIII; d. phylogenetic species in Clade VII; e. isolates representing F. nirenbergiae.

Taxonomy

In this section we provide a new (emended) description of F. oxysporum and designate an epitype for this species. The following species are also recognised as new within the FOSC, based on phylogenetic inference and morphological comparisons. Isolates CBS 128.81, CBS 680.89 and CBS 130323 in Clade III are not treated further as these were sterile.

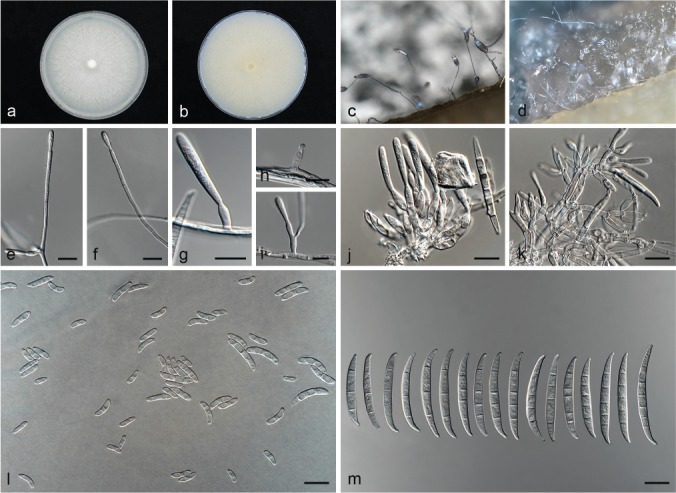

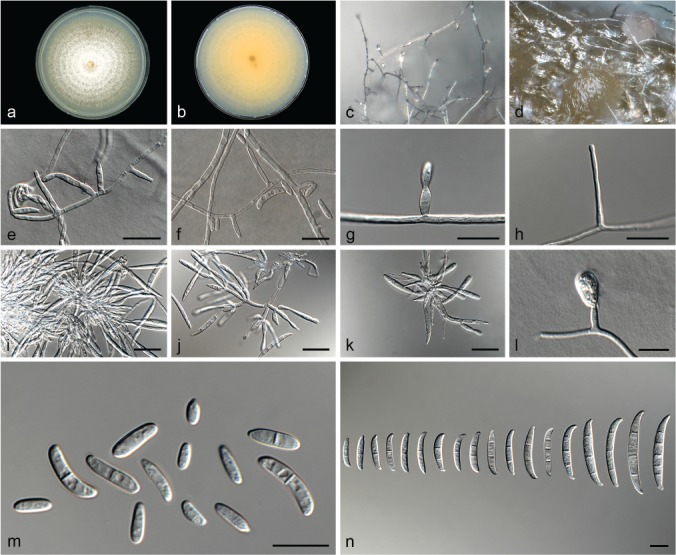

Fusarium callistephi L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826833; Fig. 3

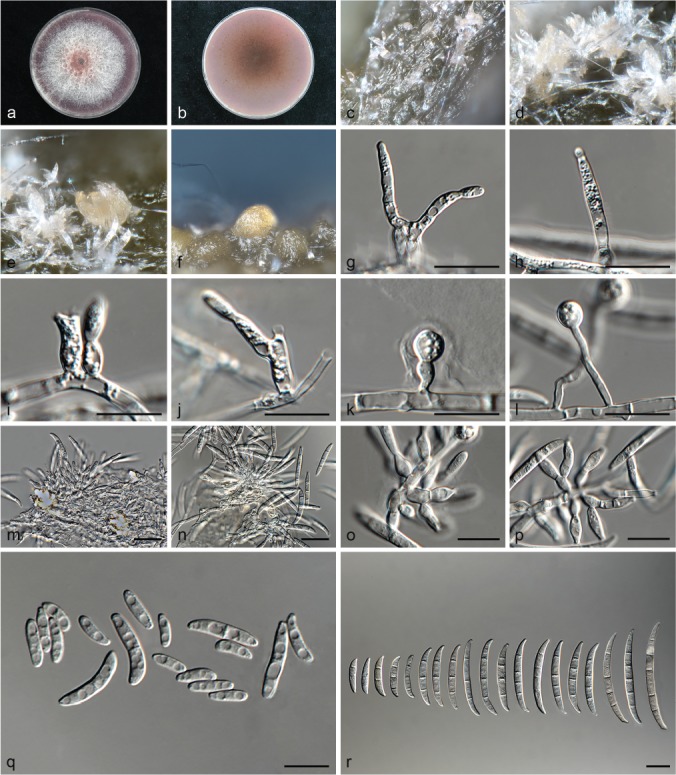

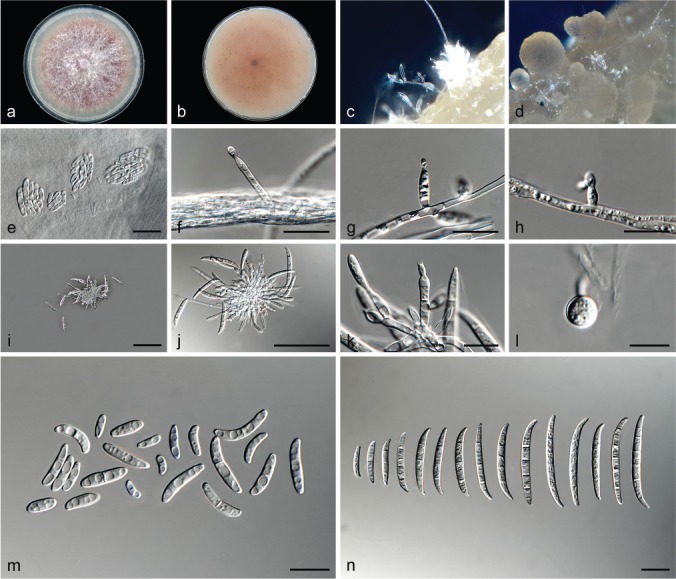

Fig. 3.

Fusarium callistephi (ex-type culture CBS 187.53). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; d. sporodochia on carnation leaves; e–i. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; j–k. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; l. aerial conidia (microconidia); m. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: e–m = 10 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the plant genus Callistephus from which this fungus was isolated.

Typus. Netherlands, Oostenbrink, from Callistephus chinensis, 28 Feb. 1953, collector unknown (holotype CBS H-23608 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 187.53).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 60–110 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 2–23 × 3–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (6–)7–11(–14) × 2–3 μm (av. 9 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (13–)14–18(–20) × 2–4 μm (av. 16 × 3 μm). Sporodochia pale luteous to pale rosy vinaceous, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 4–7 × 2–4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 9–13 × 3–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, 3–4(–5)-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 3-septate conidia: (28–)33–39(–40) × 3–5 μm (av. 36 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (30–)35–41(–42) × 3–5 μm (av. 38 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: 36–44(–47) × 4–5 μm (av. 40 × 5 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 2.9–4.2 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface white to pale vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse colourless, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, lacking chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with moderate sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale luteous to pale rosy vinaceous sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional material examined. South Africa, Western Cape Province, Piketberg, from Agathosma betulina, 2001, K. Lubbe, CBS 115423 = CPC 5311.

Notes — Fusarium callistephi formed a highly-supported subclade in Clade III, closely related to F. cugenangense, F. elaeidis and the untreated Fusarium clade. This species (conidia 3–4(–5)-septate) can be distinguished from F. cugenangense (conidia 3–6-septate; Maryani et al. 2019) and F. elaeidis ((1–)3–5-septate) based on septation of their macroconidia. Additionally, F. cugenangense produces up to 3-septate microconidia, a feature not seen in either F. callistephi or F. elaeidis. Fusarium elaeidis readily formed polyphialidic conidiogenous cells on the aerial mycelium, not seen in F. callistephi.

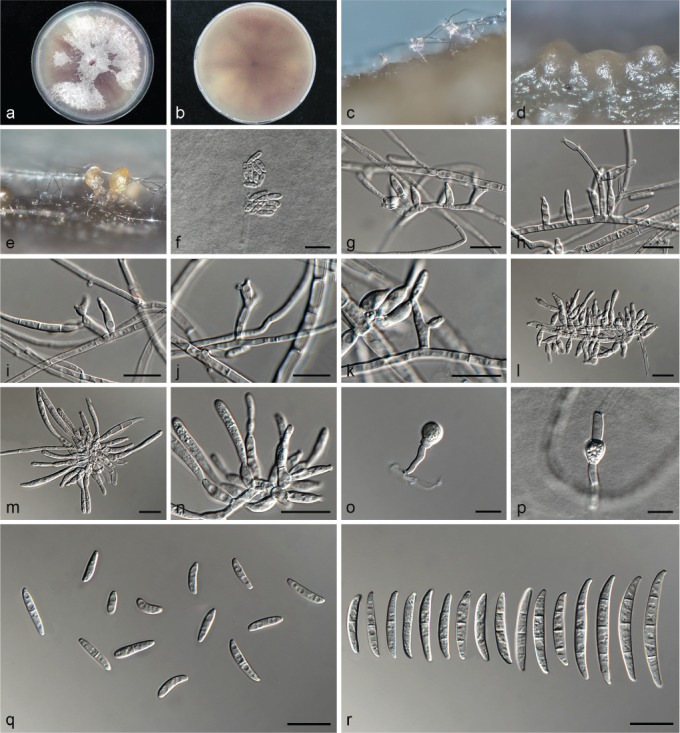

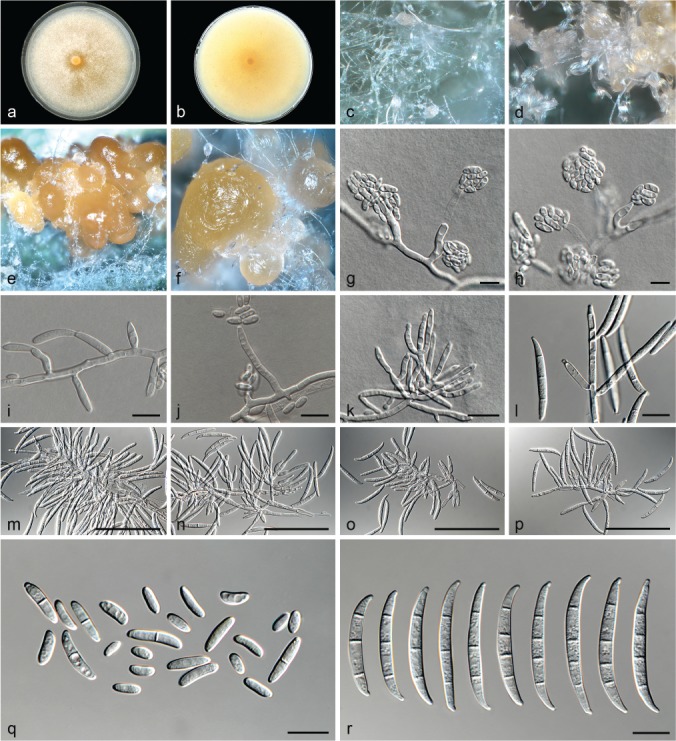

Fusarium carminascens L. Lombard, Crous & Lampr., sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826835; Fig. 4

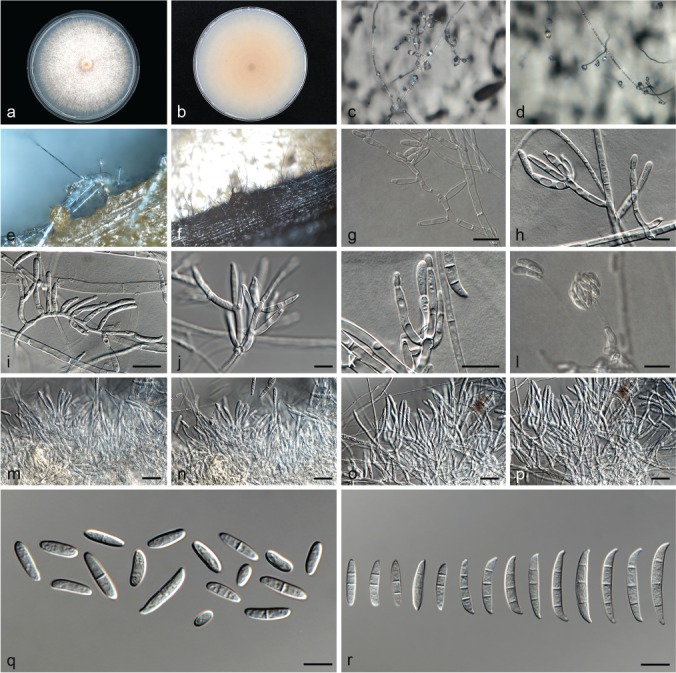

Fig. 4.

Fusarium carminascens (ex-type culture CBS 144738). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e–f. sporodochia on carnation leaves; g–j. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; g–h. monophialides; i–j. polyphialides; k–l. chlamydospores; m–p. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; o–p. phialides of sporodochial conidiophores; q. aerial conidia (microconidia); r. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: g–r = 10 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the almost carmine exudates this fungus produces in its aerial mycelium when grown on PDA.

Typus. South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal Province, from Zea mays, 2008, S.C. Lamprecht (holotype CBS H-23609 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 144738 = CPC 25800).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 35–55 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily phialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 8–18 × 3–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (5–)7–11(–12) × 2–3(–4) μm (av. 9 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (12–)13–15(–18) × 2–4 μm (av. 14 × 3 μm). Sporodochia bright orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 4–9 × 2–4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 5–13 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (2–)3–4(–5)-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 2-septate conidia: 16–19 × 3–4 μm (av. 18 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (21–)26–36(–40) × 3–5 μm (av. 31 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (31–)33–43(–44) × 4–5 μm (av. 38 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: 45–51 × 4 μm (av. 48 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally, 4–8 μm diam.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.1–4.0 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface vinaceous purple to livid purple, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium which produce an almost carmine exudate; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse dark livid to livid purple, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, with abundant chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant bright orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal Province, from Zea mays, 2008, S.C. Lamprecht, CBS 144739 = CPC 25792, CBS 144740 = CPC 25793, CBS 144741 = CPC 25795.

Notes — Fusarium carminascens formed a well-supported subclade in Clade III, closely related to F. fabacearum and F. glycines. This species produced an almost carmine coloured exudate in its aerial mycelium, a feature not observed in any of the other strains studied here. Furthermore, F. carminascens produces polyphialidic conidiogenous cells on its aerial mycelium, not observed in F. fabacearum or F. glycines.

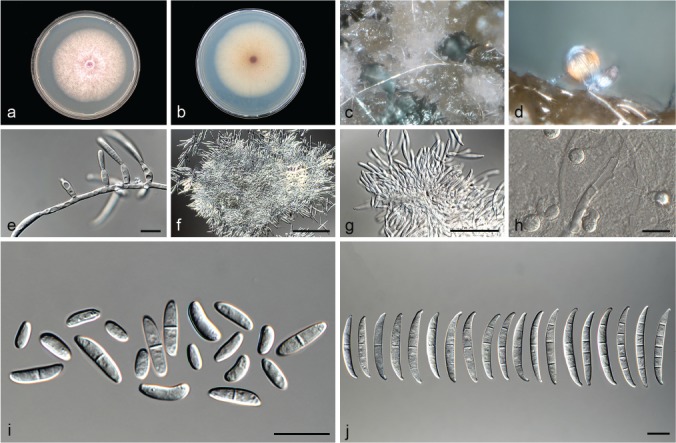

Fusarium contaminatum L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — Myco-Bank MB826836; Fig. 5

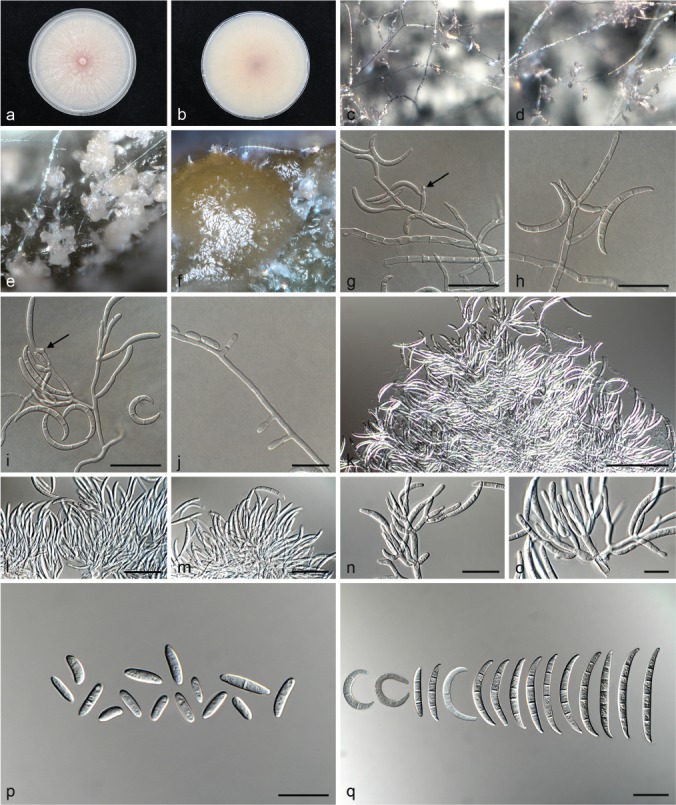

Fig. 5.

Fusarium contaminatum (ex-type culture CBS 114899). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. Surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e–f. sporodochia on carnation leaves; g–k. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; l. false head carried on phialide on aerial mycelium; m–p. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; q. aerial conidia (microconidia); r. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: g–l, q–r = 10 μm; m–p = 20 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the fact that this fungus was isolated from contaminated food products.

Typus. Germany, Schluchtern, from pasteurized chocolate milk, Apr. 2004, J. Houbraken (holotype CBS H-23610 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 114899).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 15–85 μm tall, unbranched or branched, bearing a single terminal or a whorl of 2–4 monophialides or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 7–22 × 2–5 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: 5–9(–11) × 2–4 μm (av. 7 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (9–)10–14(–17) × 2–4 μm (av. 12 × 3 μm). Sporodochia bright orange, formed sparsely on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 7–13 × 4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 4–9 × 2–3 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (2–)3-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 2-septate conidia: (14–)15–17 × 3–4 μm (av. 16 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (18–)20–26(–28) × 3–5 μm (av. 23 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.1–4.5 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface white to pale vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse rosy vinaceous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, lacking chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. Netherlands, from pasteurized fruit juice, date and collector unknown, CBS 111552; from tetra pack with milky nutrition, 2005, collector unknown, CBS 117461.

Notes — Fusarium contaminatum formed a highly-supported subclade in Clade VII, closely related to F. pharetrum and F. veterinarium. This species produces small, 2–3-septate macroconidia, whereas F. pharetrum produces much larger, 3(–4)-septate macroconidia and F. veterinarium produces slightly smaller, 1–(2–)3-septate macroconidia. None of these three species produced any chlamydospores on SNA.

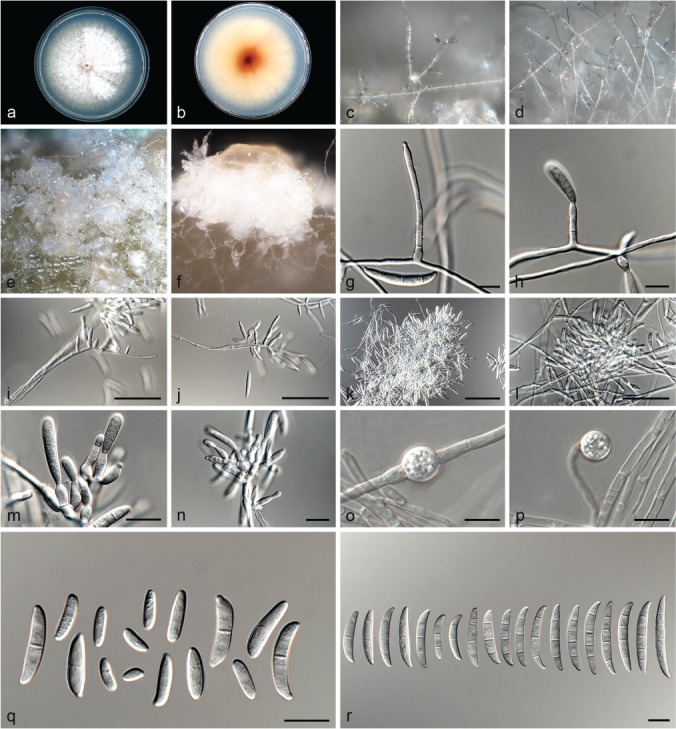

Fusarium curvatum L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826837; Fig. 6

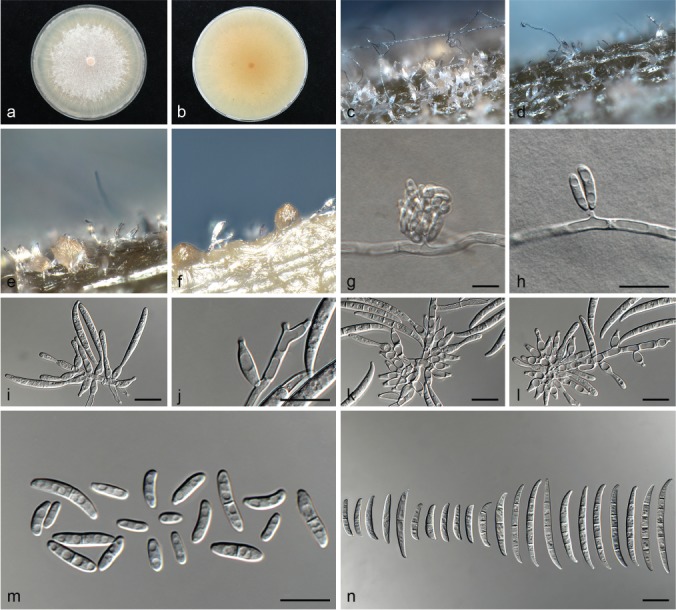

Fig. 6.

Fusarium curvatum (ex-type culture CBS 238.94). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e–f. sporodochia on carnation leaves; g–i. conidiophores, monophialides and polyphialides (arrows) on aerial mycelium; j. phialidic pegs on aerial mycelium; k–o. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; p. aerial conidia (microconidia); q. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: g–i, n = 20 μm; j, o–q = 10 μm, k–m = 50 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the strongly curved sporodochial conidia produced by this fungus.

Typus. Netherlands, from Beaucarnia sp., 1994, J.W. Veenbaas-Rijks (holo-type CBS H-23611 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 238.94 = NRRL 26422 = PD 94/184).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 25–56 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily phialides, often reduced to single phialides or as phialidic pegs; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 3–30 × 2–5 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (4–)5–9(–11) × 2–4 μm (av. 7 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (10–)11–13 × 2–4 μm (av. 12 × 3 μm). Sporodochia orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 8–10 × 2–4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 8–22 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, strongly curved or curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (2–)3–5-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 2-septate conidia: (15–)16–22(–23) × 3–4 μm (av. 19 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (18–)27–39(–41) × 3–5 μm (av. 33 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (34–)37–43(–46) × 3–5 μm (av. 40 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: (30–)38–46(–51) × 3–5 μm (av. 42 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.1–4.5 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface pale vinaceous to rosy vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse pale vinaceous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, lacking chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. Germany, Berlin-Dahlem, from Matthiola incana, Feb. 1957, W. Gerlach, CBS 247.61 = BBA 8398 = DSM 62308 = NRRL 22545. – Netherlands, from Hedera helix, 1994, J.W. Veenbaas-Rijks, CBS 141.95 = NRRL 36251 = PD 94/1518.

Notes — Fusarium curvatum formed a highly-supported subclade in Clade VIII, closely related to F. nirenbergiae. This species produces strongly curved 3-septate macroconidia and aerial polyphialidic conidiogenous cells, distinguishing it from F. nirenbergiae. Additionally, F. curvatum failed to produce any chlamydospores on SNA, whereas F. nirenbergiae produced abundant chlamydospores.

Fusarium elaeidis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826838; Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Fusarium elaeidis (ex-type culture CBS 217.49). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e–f. sporodochia on carnation leaves; g. false head carried on a phialidic peg on aerial mycelium; h. phialidic peg; i–j. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; j. polyphialide; k–l. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; m. aerial conidia (microconidia); n. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: g–n = 10 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the host plant genus Elaeis, from which this fungus was first isolated.

Typus. Zaire, from Elaeis sp., 1949, T. Gogoi (holotype CBS H-23612 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 217.49 = NRRL 36358).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 25–65 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily phialides, often reduced to single phialides or as phialidic pegs; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 3–14 × 3–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: 6–10(–13) × 2–3 μm (av. 8 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (9–)11–15(–17) × 2–4(–5) μm (av. 13 × 3 μm). Sporodochia pale rosy vinaceous to orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 3–9 × 2–3 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 8–12 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (1–)3–5-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: (14–)15–25(–32) × 2–4 μm (av. 20 × 3 μm); 2-septate conidia: (17–)19–25 × 3–4 μm (av. 22 × 4 μm); 3-septate conidia: (22–)30–40(–46) × (2–)3–4 μm (av. 35 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (34–)36–40(–43) × 3–5 μm (av. 38 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: (36–)37–43(–50) × 3–5 μm (av. 40 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 2.6–3.4 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface pale rosy vinaceous grey, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse pale rosy vinaceous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, lacking chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale rosy vinaceous to orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. Zaire, from Elaeis sp., 1949, T. Gogoi, CBS 218.49 = NRRL 36359. – Unknown locality, from Elaeis guineensis, 1952, J. Fraselle, CBS 255.52 = NRRL 36386.

Notes — Fusarium elaeidis formed a highly-supported subclade in Clade III, closely related to F. callistephi, F. cugenangense and the untreated Fusarium clade. See notes under F. callistephi for distinguishing morphological features.

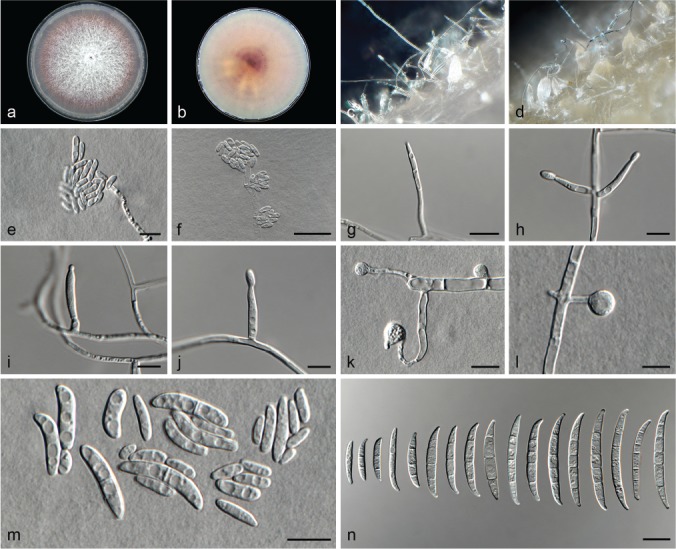

Fusarium fabacearum L. Lombard, Crous & Lampr., sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826839; Fig. 8

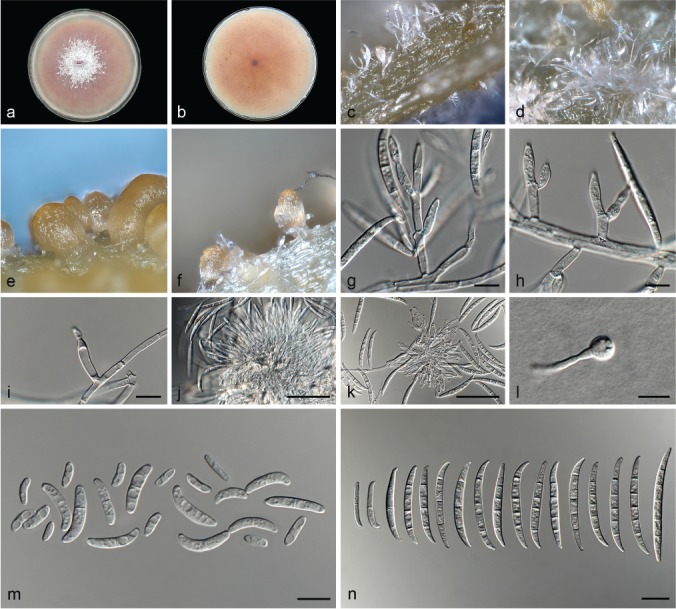

Fig. 8.

Fusarium fabacearum (ex-type culture CBS 144743). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; d. sporodochia on carnation leaves; e. false head carried on a phialide on aerial mycelium; f–h. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; i–k. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; l. chlamydospore; m. aerial conidia (microconidia); n. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: e–h, k–n = 10 μm; i–j = 50 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the plant family, Fabaceae, which includes the plant host Glycine max from which this fungus was first isolated.

Typus. South Africa, North West Province, from Glycine max, 2010, S.C. Lamprecht (holotype CBS H-23613 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 144743 = CPC 25802).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 25–50 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 11–15 × 3–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (4–)5–9(–13) × 2–3 μm (av. 7 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (12–)13–15(–16) × 3–4 μm (av. 14 × 3 μm). Sporodochia pale luteous to orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 4–7 × 3 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 7–10 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (1–)3–4(–5)-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: (15–)16–24(–25) × 3–4 μm (av. 20 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (24–)27–33(–36) × (2–)3–5 μm (av. 30 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (32–)33–37(–40) × 3–5 μm (av. 35 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: (35–)38–44 × 3–4 μm (av. 41 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally, 5–8 μm diam.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.0–4.4 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface pale vinaceous grey to vinaceous grey, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse pale vinaceous grey, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, with abundant chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale luteous to orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. South Africa, North West Province, from Glycine max, 2010, S.C. Lamprecht, CBS 144744 = CPC 25803; from Zea mays, 2008, C.M. Bezuidenhout, CBS 144742 = CPC 25801.

Notes — Fusarium fabacearum formed a highly-supported subclade in Clade III, closely related to F. carminascens and F. glycines. See notes under F. carminascens for distinguishing morphological features.

Fusarium glycines L. Lombard, Crous & Lampr., sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826840; Fig. 9

Fig. 9.

Fusarium glycines (ex-type culture CBS 144746). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e–f. sporodochia on carnation leaves; g–i. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; j–k. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; l. chlamydospore; m. aerial conidia (microconidia); n. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: g–i, l–n = 10 μm; j–k = 50 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the plant genus Glycine from which this fungus was isolated.

Typus. South Africa, North West Province, from Glycine max, 2010, S.C. Lamprecht (holotype CBS H-23614 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 144746 = CPC 25808).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 5–45 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 15–25 × 2–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: 7–11(–13) × 3–4 μm (av. 9 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (13–)14–16(–18) × 3–4 μm (av. 15 × 3 μm). Sporodochia bright orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thinwalled stipe, 4–9 × 2–4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 12–14 × 2–5 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (1–)3–5-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: 20–25 × 3–4 μm (av. 23 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: 37–43(–48) × 4–5 μm (av. 38 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: 44–46(–51) × 4–5 μm (av. 42 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: 43–49(–52) × 4–5 μm (av. 46 × 4 μm).

Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally, 4–8 μm diam.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.0–4.4 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse vinaceous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, with abundant chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant bright orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. Argentina, substrate unknown, date unknown, C.J.M. Carrera, CBS 214.49 = NRRL 36356 = LCF F-245. – Italy, from Ocimum basilicum, 1989, G. Tamiette & A. Matta, CBS 200.89. – South Africa, North West Province, from Glycine max, 2010, S.C. Lamprecht, CBS 144745 = CPC 25804. – Unknown locality, from Linum usitatissium, 1933, E.C. Stakman, CBS 176.33 = NRRL 36286.

Notes — Fusarium glycines formed a highly-supported subclade in Clade III, closely related to F. carminascens and F. fabacearum. See notes under F. carminascens for distinguishing morphological features.

Fusarium gossypinum L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826841; Fig. 10

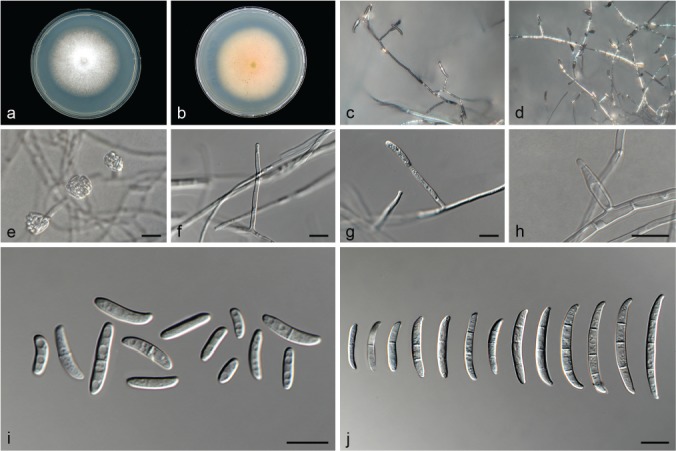

Fig. 10.

Fusarium gossypinum (ex-type culture CBS 116613). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e. false head carried on a phialide on aerial mycelium; f–h. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; i. aerial conidia (microconidia); j. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: e = 20 μm; f–j = 10 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the plant genus Gossypium from which this fungus was isolated.

Typus. Ivory Coast, Bouaké, wilted Gossypium hirsutum, Sept. 1995, K. Abo (holotype CBS H-23615 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 116613).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 35–75 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 3–30 × 2–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent. Microconidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (5–)6–8(–11) × 2–4 μm (av. 7 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (11–)12–14(–15) × 2–4 μm (av. 15 × 3 μm). Macroconidia also formed by phialides on aerial mycelium, falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (1–)3-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: 16–18 × 3 μm (av. 17 × 3 μm); 2-septate conidia: 21–23 × 3–4 μm (av. 22 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (24–)27–35(–38) × 3–4 μm (av. 31 × 4 μm). Sporodochia absent. Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 1.6–2.8 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface white to pale rosy vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse pale rosy vinaceous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, lacking chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse lacking sporodochia on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. Ivory Coast, Bouaké, wilted Gossypium hirsutum, Sept. 1995, K. Abo, CBS 116611 and CBS 116612.

Notes — Fusarium gossypinum formed a unique highly-supported subclade in Clade III. This species failed to produce any sporodochia on the carnation leaf pieces, but still produced abundant 3-septate macroconidia on the aerial mycelium. Other species included in Clade III, all readily produced sporodochia on carnation leaves.

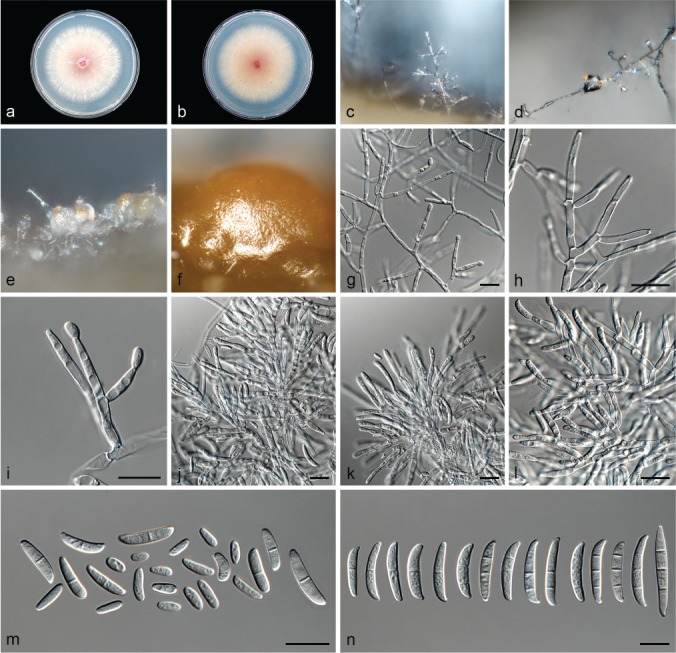

Fusarium hoodiae L. Lombard, Crous & Lampr., sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826842; Fig. 11

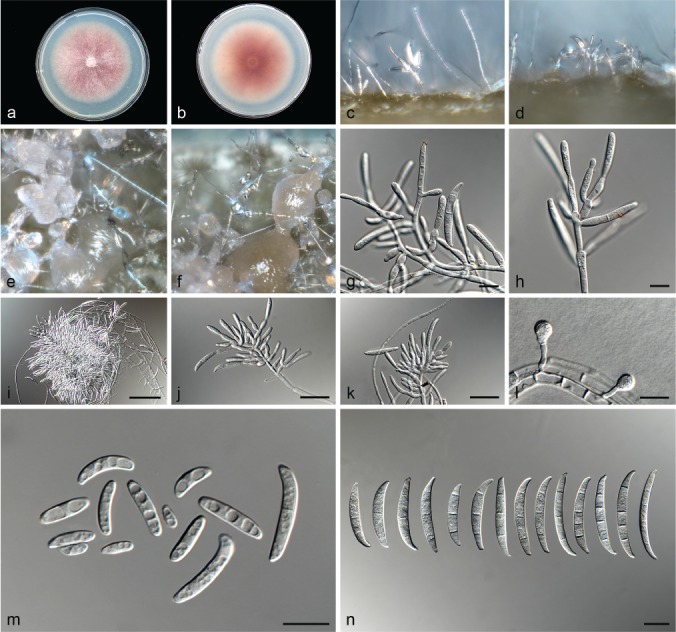

Fig. 11.

Fusarium hoodiae (ex-type culture CBS 132474). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–d. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; e–f. sporodochia on carnation leaves; g–h. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; i–k. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; l. chlamydospore; m. aerial conidia (microconidia); n. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: g–h, l–n = 10 μm; i = 50 μm; j–k = 20 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the plant genus Hoodia from which this fungus was isolated.

Typus. South Africa, Northern Cape Province, Prieska, root of Hoodia gordonii, 2002, O.A. Philippou (holotype CBS H-23616 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 132474).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 40–60 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 15–24 × 2–3 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (5–)6–10(–16) × 2–4 μm (av. 8 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (11–)12–16(–17) × 3–4 μm (av. 14 × 3 μm). Sporodochia pale vinaceous to light orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 7–11 × 3–5 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 7–13 × 2–5 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, (1–)3(–4)-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: 20–33 × 3–5 μm (av. 25 × 4 μm); 3-septate conidia: (20–)27–39(–45) × 3–5 μm (av. 33 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (35–)36–46(–51) × 4–5 μm (av. 41 × 5 μm). Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally, 4–11 μm diam.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.1–4.5 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface pale vinaceous grey to livid vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse livid purple to pale vinaceous grey, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, with abundant chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale vinaceous to light orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. South Africa, Northern Cape Province, Prieska, root of Hoodia gordonii, 2002, O.A. Philippou, CBS 132476, CBS 132477.

Notes — Fusarium hoodiae formed a weakly supported clade constituting Clade IV in this phylogenetic study. All three isolates studied here, produced pale vinaceous to pale orange sporodochia on the carnation leaf pieces, unique for all the isolates studied.

Fusarium languescens L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826843; Fig. 12

Fig. 12.

Fusarium languescens (ex-type culture CBS 645.78). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; d. sporodochia on carnation leaves; e–h. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; i–k. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; l. chlamydospore; m. aerial conidia (microconidia); n. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: e–h, l–n = 10 μm; i–k = 20 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to the wilting symptoms associated with infections of this fungus.

Typus. Morocco, Solanum lycopersicum, date and collector unknown (holo-type CBS H-23617 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 645.78 = NRRL 36531).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 25–30 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 7–22 × 2–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (4–)5–9(–12) × 2–3 μm (av. 7 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (9–)11–15 × 2–4 μm (av. 13 × 3 μm). Sporodochia light orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 5–10 × 3–4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 10–14 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, 1–3(–5)-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: (15–)18–23(–30) × 3–4 μm (av. 20 × 3 μm); 2-septate conidia: (14–)16–22(–24) × 4 μm (av. 19 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (22–)26–38(–47) × 3–5 μm (av. 32 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: 32–40 × 4–5 μm (av. 36 × 5 μm). Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally, 6–9 μm diam.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 3.1–4.5 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface flesh to rosy vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse pale luteous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, with abundant chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant light orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. Israel, Bet Dagan, Solanum lycopersicum, 1986, R. Cohn, CBS 413.90 = ATCC 66046 = NRRL 36465. – Morocco, Solanum lycopersicum, date and collector unknown, CBS 646.78 = NRRL 36532. – Netherlands, Solanum lycopersicum, 1991, D.H. Elgersma, CBS 300.91 = NRRL 36416, CBS 302.91 = NRRL 36419. – South Africa, Zea mays, date and collector unknown, CBS 119796 = MRC 8437. – Unknown locality, Solanum lycopersicum, date and collector unknown, CBS 872.95 = NRRL 36570.

Notes — Fusarium languescens forms the highly-supported Clade VI, which mostly includes strains associated with tomato wilt. This species displays morphological overlap with several species treated here. Therefore, phylogenetic inference is needed to accurately identify this species.

Fusarium libertatis L. Lombard, Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826844; Fig. 13

Fig. 13.

Fusarium libertatis (ex-type culture CBS 144749). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c–e. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; g–k. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; g–h. monophialides; i–k. polyphialides; l–n. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; n. phialides of sporodochial conidiophores; o–p. chlamydospores; q. aerial conidia (microconidia); r. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: c–r = 10 μm.

Etymology. Name refers to ‘freedom’. Fusarium libertatis was isolated from the rock surfaces in the stone quarry on Robben Island where the prisoners were forced to work. It is named in remembrance of all those who through the centuries were incarcerated on the Island for their different political beliefs.

Typus. South Africa, Western Cape Province, Robben Island, Van Riebeeck’s Quarry, from rock surfaces, May 2015, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS H-23618 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 144749 = CPC 28465).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 2–30 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily phialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 8–13 × 2–4 μm, sometimes proliferating percurrently, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (6–)7–9(–11) × 2–4 μm (av. 8 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (11–)12–14(–15) × 2–4 μm (av. 13 × 3 μm). Sporodochia bright orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 4–8 × 3–4 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 6–12 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, 1–3-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: (15–)17–21(–23) × 2–4 μm (av. 19 × 3 μm); 2-septate conidia: (18–)20–24(–25) × 2–3(–4) μm (av. 22 × 4 μm); 3-septate conidia: (24–)30–38(–40) × (2–)3–5 μm (av. 34 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally and intercalarily, carried singly, 5–9 μm diam.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA with an average radial growth rate of 2.3–4.4 mm/d at 24 °C. Colony surface vinaceous, floccose with abundant aerial mycelium; colony margins irregular, lobate, serrate or filiform. Odour absent. Reverse vinaceous, lacking diffusible pigment. On SNA, hyphae hyaline, smooth-walled, with abundant chlamydospores, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant sporulation on the medium surface. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant bright orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves.

Additional materials examined. South Africa, Western Cape Province, from Aspalathus sp., 2008, C.M. Bezuidenhout, CBS 144747 = CPC 25788, CBS 144748 = CPC 25782.

Notes — Fusarium libertatis formed a unique well-supported clade Clade (II). This species readily produced polyphialidic conidiogenous cells on its aerial mycelium and can be distinguished from the other species (F. carminascens, F. curvatum and F. elaeidis) found to produce polyphialides by only producing up to 3-septate macroconidia, whereas the other polyphialidic species produce up to 5-septate macroconidia.

Fusarium nirenbergiae L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB826845; Fig. 14

Fig. 14.

Fusarium nirenbergiae (ex-type culture CBS 840.88). a–b. Colony on PDA; a. surface of colony on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C under continuous white light; b. reverse of colony on PDA; c. conidiophores on surface of carnation leaf; d. sporodochia on carnation leaves; e. conidiophores and phialides on aerial mycelium; f–g. sporodochia and sporodochial conidiophores; h. chlamydospore; i. aerial conidia (microconidia); j. sporodochial conidia (macroconidia). — Scale bars: e, h–j = 10 μm; f–g = 50 μm.

Etymology. Named in honour of Prof. H.I. Nirenberg for her contribution to our understanding of Fusarium taxonomy.

Typus. Netherlands, Aalsmeer, from Dianthus caryophyllus, 1988, H. Rattink (holotype CBS H-23619 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 840.88).

Conidiophores carried on the aerial mycelium 18–50 μm tall, unbranched or sparingly branched, bearing terminal or intercalarily monophialides, often reduced to single phialides; aerial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 8–24 × 2–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to falcate, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (5–)6–10(–11) × 2–4 μm (av. 8 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (9–)10–14(–15) × 2–4 μm (av. 12 × 3 μm). Sporodochia bright orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Conidiophores in sporodochia verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe, 6–14 × 3–5 μm, bearing apical whorls of 2–3 monophialides or rarely as single lateral monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 8–18 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally with almost parallel sides tapering slightly towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt to foot-like basal cell, 1–5-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: 15–29(–34) × 3–4 μm (av. 22 × 4 μm); 2-septate conidia: (18–)19–31(–39) × 2–4(–5) μm (av. 25 × 3 μm); 3-septate conidia: (30–)32–40(–43) × 3–4 μm (av. 36 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (34–)36–44(–48) × 3–5 μm (av. 40 × 4 μm); 5-septate conidia: (36–)43–59(–66) × 3–5 μm (av. 51 × 4 μm). Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, formed terminally, 4–6 μm diam.