Abstract

Several studies have reported the detection of herpesviruses (HVs) in bats. However, the prevalence and phylogenetic characteristics of HVs in bats are still poorly understood. To elucidate the epidemiological characteristics of bat HVs in southern China, 520 fecal samples from eight bat species were collected in four geographic regions of southern China. Of these samples, 73 (14.0 %) tested positive for HVs using nested polymerase chain reaction assay. Phylogenetic analysis revealed a high degree of molecular diversity of HVs in bats of different species from different geographic regions. Our study provides evidence for co-evolution of bats and HVs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00705-015-2614-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Herpesviruses, Bat, Phylogeny, Diversity, Southern China

It is known that bats harbor a variety of viruses. Recently, the number and diversity of viruses identified in bats has been increasing [1]. Although most viruses that have been isolated from or detected in bats are unlikely to infect humans, some can spill over to humans and cause deadly emerging diseases, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome and diseases caused by Ebola virus, Nipah virus, lyssaviruses, Japanese encephalitis virus, coronaviruses and Hendra virus [2–5], indicating that bats are a significant potential source of emerging zoonotic diseases. Understanding the spectrum and characteristics of viruses that bats carry may help prevent and control potential emerging bat-borne diseases.

Herpesviruses (HVs) are large, enveloped, double-strand DNA viruses that infect the skin, mucosal membrane, lymphatic system and nervous system of animals, disseminating in various vertebrate hosts, including humans [6]. The family Herpesviridae is divided into three subfamilies: Alphaherpesvirinae, Betaherpesvirinae and Gammaherpesvirinae. In 2007, Wibbelt and co-workers first confirmed the presence of HVs in bats [7]. Recently, several studies have documented the high prevalence of HVs with diverse genetic characteristics in bats originating from the Philippines, Madagascar, Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, Germany, and Hungary [8–12]. In 2012, four new HVs, two betaherpesviruses and two gammaherpesviruses, were identified in bats in China, using sequence-independent PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing technology, targeting the concatenated glycoprotein B (gB) and DNA-directed DNA polymerase (DPOL) genes of HVs [13]. However, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding the prevalence and phylogenetic characteristics of bat-derived HVs in mainland China. Furthermore, little is known about the tissue distribution and the route of viral shedding of bat herpesviruses.

In this study, we report the prevalence of HVs in fecal samples collected from different bat species in four geographic regions of Guangdong and Hainan provinces in southern China. We also report the phylogenetic characteristics of the identified HVs in different bat species.

Fecal sample collection from bats was performed in Hainan (Haikou city) and Guangdong province (Huizhou, Guangzhou and Yunfu city), southern China. The sampling method has been described previously [14]. Bat species identification was confirmed by amplification and sequencing of the cytochrome B (cytB) gene, which is a commonly used technique in archeology [15].

For initial detection of HVs, nested PCR targeting the highly conserved amino acid motifs in the DPOL gene of HVs was performed using the consensus primer sets ILK, DFA, TGV, KG1 and IYG [16]. Because the high level of sequence diversity within the subfamily Betaherpesvirinae constituted major challenges for designing degenerate primers, and because Gammaherpesvirinae was the predominant subfamily in our study, we specifically tested representative gammaherpesvirus-positive samples with the deg/dI nested-primer set RH-gB [7], which targets glycoprotein B (gB) gene of the Gammaherpesvirinae subfamily members (approximately 450 bp in length, without primer-binding sites). A positive sample (human herpesvirus 6) and a negative control (sterile water) were included in each reaction system.

Sequence editing and identity calculations were conducted using BioEdit, version 7.0.4. Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were compared with sequences in the GenBank database using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and aligned using Clustal W [17]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using Clustal W version 2.0 and MEGA 6 [18] by the neighbor-joining algorithm and the maximum-likelihood method. Bootstrap values of the constructed phylogenetic trees were generated by conducting 1,000 replicates.

The GenBank accession numbers for the nucleotide sequences of the partial DPOL and gB genes of bat HVs detected in the present study are KR261841-KR261921. For comparative genetic analysis, other HVs genomes were retrieved from GenBank, including alcelaphine herpesviruses (AlHV-1, NC_002531; AlHV-2, NC_024382), bat rhadinovirus 1 (DQ788628), Bat simplexvirus 1 (ACJ02393), bovine herpesviruses (BoHV-4, AF318573; BoHV-6, NC_024303), canine herpesvirus (CaHV-1, AY949827), cercopithecine herpesvirus (CeHV-5, NC_012783), feline herpesvirus (FeHV-1, AJ224971), equid herpesvirus (EH-2, HQ247788), Egyptian fruit bat betaherpesvirus (Egyptian FBBV, FJ797654), Egyptian fruit bat gammaherpesvirus (Egyptian FBGV, ACY82599), human herpesviruses (HHV-3, X04370; HHV-4, EF187849; HHV-6, CZ258588; HHV-7, CN950643; HHV-8, U93872), macacine herpesvirus (MaHV-4, NC_006146), murine herpesvirus (MurHV-72, AFM85236), Myotis ricketti herpesvirus 2 (MrHV-2, JN692430), mustelid herpesvirus 1 (MuHV-1, AF376034) and ovine herpesvirus 2 (Ovine-2, DQ198083).

Between 2011 and 2014, 520 fecal specimens from eight bat species (four families) were initially tested for a 170-bp region of the DPOL gene of HVs. A total of 73 (14.04 %) of 520 samples tested positive for HVs in all bat species, including Hipposideros pomona (11.11 %, 1/9), Hipposideros larvatus (6.67 %, 1/15), Myotis ricketti (28.57 %, 2/7), Miniopterus schreibersi (3.47 %, 5/144), Scotophilus kuhlii (20.90 %, 37/177), Emballonuroidea (33.33 %, 1/3), Rhinolophus blythi (16.50 %, 17/103) and Cynopterus sphinx (15.0 %, 9/60) (Table 1 and E-Figure 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of bat herpesviruses in this study by geography and bat species

| Bat species | Specimen collection site | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huizhou (Aug 2011) | Hainan (Oct 2011) | Haikou (Jul 2013) | Guangzhou (Sep 2012) | Guangzhou (Nov 2014) | Yunfu (Dec 2013) | |||

| No. (+) | No. (+) | No. (+) | No. (+) | No. (+) | No. (+) | No. (+) | Positive % | |

| Hipposideridae | ||||||||

| Hipposideros larvatus | 10 (0) | 2 (1) | 3 (0) | – | – | – | 15 (1) | 6.7 |

| Hipposideros pomona | 1 (0) | 5 (1) | 3 (0) | – | – | – | 9 (1) | 11.1 |

| Vespertilionidae | ||||||||

| Myotis ricketti | 2 (0) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | – | – | – | 7 (2) | 28.6 |

| Miniopterus schreibersi | – | 105 (4) | 39 (1) | – | – | – | 144 (5) | 3.5 |

| Scotophilus kuhlii | 13 (3) | – | 1 (0) | – | – | 163 (34) | 177 (37) | 20.9 |

| Emballonuroidea | 3 (1) | – | – | – | – | – | 3 (1) | 33.3 |

| Rhinolophidae | ||||||||

| Rhinolophus blythi | – | – | 20 (1) | – | – | 83 (16) | 103 (17) | 16.5 |

| Cynopterus sphinx | – | – | 30 (1) | 4 (1) | 26 (7) | – | 60 (9) | 15.0 |

| Total | 29 (4) | 114 (7) | 100 (4) | 4 (1) | 26 (7) | 247 (50) | 520 (73) | 14.0 |

No., the number of bats collected; (+), the number of bats that were positive for herpesviruses; positive%, the positive detection rate of herpesviruses in different bat species

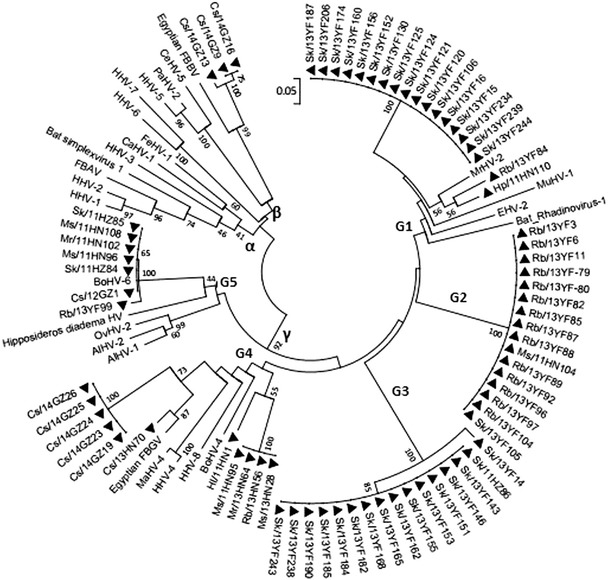

Phylogenetic analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences of the partial DPOL revealed that bat HVs were clustered into two subfamilies: Betaherpesvirinae (4 isolates) and Gammaherpesvirinae (69 isolates). No members of the Alphaherpesvirinae were detected in the present study.

The members of the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae can be divided into five subgroups: G1 includes members of the genus Percavirus detected in mustelids and equids; G4 includes members of the genera Rhadinovirus and Lymphocryptovirus detected in humans, bovines and maccines; G5 includes members of the genus Macavirus detected in ovines and alcelaphines; and G2 and G3 constitute the ‘bat-only’ group. In G1, G4, and G5, ‘bat clades’ were prominent and separated from other originally proposed clades. In G1 (the genus Percavirus), 33 HVs branched together to form a ‘bat-only’ group. Within this cluster, two subgroups of viruses were identified. One subgroup consisted of HVs detected in Scotophilus kuhlii, and the other subgroup comprised the majority of the viruses detected in Rhinolophus blythi. Interestingly, seven isolates in G5 from bats in Huizhou, Guangzhou and Yunfu city branched together with a bovine herpesvirus, BOHV6, sharing 97.0-98.5 % sequence identity. Within this clade, HVs isolates from multiple bat species detected in different habitats could be found, including SK/11HZ85/84, MS/11HN108/96, HP/11HN102 and CS/12GZ1. This indicated potential interspecies transmission (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis based on a 51-amino-acid portion of the deduced amino acid sequence of the DNA-directed DNA polymerase (DPOL) of herpesviruses from bats in southern China. The tree was generated by using the neighbor-joining method with the p-distance model. A bootstrap test was replicated 1000 times. Numbers above the branches indicate NJ bootstrap values. Bold triangles indicate herpesviruses detected in the present study. CS, Cynopterus sphinx; HL, Hipposideros larvatus; HP, Hipposideros pomona; MR, Myotis ricketti; MS, Miniopterus schreibersi; RB, Rhinolophus blythi; SK, Scotophilus kuhlii; EM, Emballonuroide; YF, Yunfu; HN, Hainan province; GZ, Guangzhou; HZ, Huizhou

A comparison of DPOL amino acid sequences of HVs from bats collected in this study revealed considerable divergence, with sequence identity ranging from 22.4 to 100.0 %. Individual bats from a single species in the same habitat might harbor different herpesviruses, as pairwise comparison of the partial DPOL amino acid sequences ranged from 27.8 % to 100 %, and viruses from Cynopterus sphinx in Guangzhou, Rhinolophus blythi and Scotophilus kuhlii in Yunfu had a mean similarity of 71.1 %, 37.9 % and 40.5 %, respectively. Branched with the BOHV6, seven bat isolates in G5 shared higher amino acid similarities, ranging from 98.3 to 100.0 %, compared with other bat HVs found in this study (28.8-55.1 %). The identities of the DPOL amino acid sequences between the bat HVs and other original HVs are shown in E-Table 1.

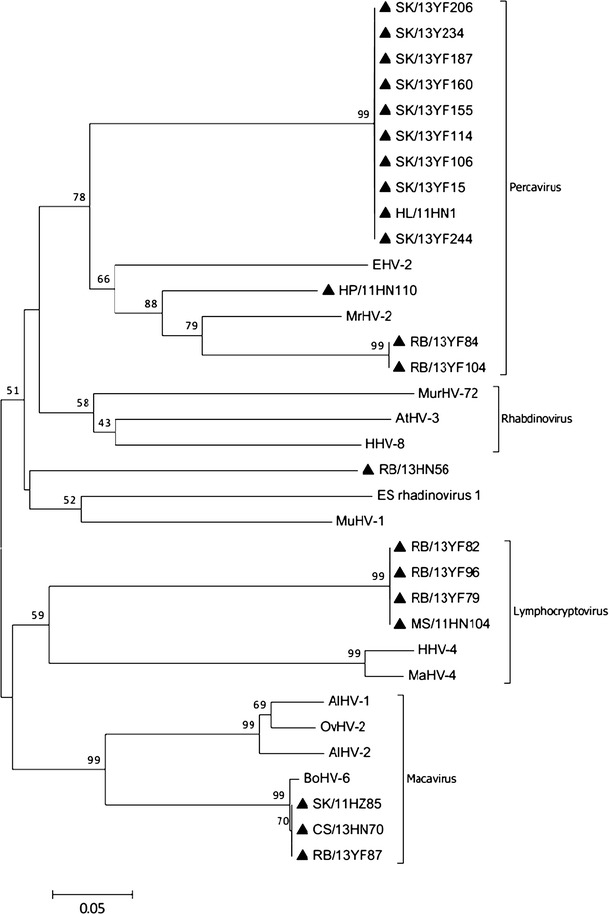

We further analyzed the phylogeny of members of the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae. Twenty-one bat virus lineages from Yunfu and Haikou city were identified within the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae, clustering into four genera to form ‘bat-only’ clades. Most genus classifications were consistent with the previously published phylogenetic tree of the DPOL gene. Twelve bat HVs (SK/13YF206/234/187/160/155/114/106/15/244, RB/13YF84/104 and HP/11HN110) clustered together with MrHV-2 and EHV-2, the members of genus Percavirus. One bat HV (Rb/13HN56) was phylogenetically related to members of the genus Rhadinovirus, despite lower bootstrap support. Three bat HVs (SK/11HZ85, CS/13HN70 and RB/13YF87) clustered together with BoHV-6, OvHV-2, AlHV-1 and AlHV-2, which collectively constitute the genus Percavirus. The remaining viruses branched together with HHV-4 and MaHV-4 to form the genus Lymphocryptovirus. We also noted that the BOHV6, from the genus Macavirus, fell within the bat HVs (SK/11HZ85, CS/13HN70 and RB/13YF87), sharing similarities of greater than 90 % with bat HVs, again suggesting potential interspecies transmissions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis based on a 151-amino-acid portion of the deduced amino acid sequence of glycoprotein B (gB) of herpesviruses from bats in southern China. The tree was generated by using the neighbor-joining method with the p-distance model. A bootstrap test was replicated 1000 times. Numbers above the branches indicate NJ bootstrap values. Bold triangles indicate herpesviruses detected in the present study. CS, Cynopterus sphinx; HL, Hipposideros larvatus; HP, Hipposideros pomona; MR, Myotis ricketti; MS, Miniopterus schreibersi; RB, Rhinolophus blythi; SK, Scotophilus kuhlii; YF, Yunfu; HN, Hainan province; HZ, Huizhou

The deduced amino acid sequences of the gB genes of bat HVs had less than 80 % identity to those of HVs from other host species, with the exception of the isolates 13YF87, 11HN70, 11HZ85 and 11HZ76 (see E-supplement 3). Deduced amino acid sequence identities of the gBs of bat HVs in this study ranged from 50.0 % to 100 %, with 65.5 % of the similarities being less than 90.0 %. BoHV-6 shared 100.0 % amino acid sequence similarity with bat HVs of the same clade, compared with only 56.2-66.4 % similarity to other bat HVs in the present study. The percentages of sequence identity to known HVs of the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae, including HVs from bats, bovines, humans, ovines, alcelaphines, murines, are shown in E-Table 2.

Viruses detected from the same sampling, within a single habitat, could be genetically diverse. For instance, the isolates SK/13YF206/187/234/155/114/106/15/244, SK/13YF104/82/96/79 and SK/13YF87 were found to belong to different genera within the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae (Percavirus, Macavirus, and Lymphocryptovirus, respectively) (Fig. 2, E-Table 2).

The prevalence of HVs of the three subfamilies in many bat species was found in previous studies to be high [7–11]. Eight bat species, with prevalence rates of 3.47-33.33 %, were sampled from four areas of southern China in this study. Of these Scotophilus kuhlii, Hipposideros larvatus, Emballonuroidea and Cynopterus sphinx were tested for HVs for the first time. These results expanded the taxonomic range of bats that can serve as hosts for HVs. Despite the high positive rate for HVs in all eight bat species, bats infected with these viruses appeared to display no overt signs of disease. The high prevalence rate, coupled with the low virulence and high diversity of HVs in bats, raises questions about whether there is co-evolution between bats and HVs.

In our study, the DPOL genes of members of the subfamilies Gammaherpesvirinae and Betaherpesvirinae shared only 25.4-35.5 % amino acid sequence identity with those of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae reported by Sasaki et al. [11] and Razafindratsimandresy et al. [9]. When compared with viruses of the same subfamily with previously reported sequences, only 39.2-71.3 % and 50.3-81.0 % sequence identity was observed in the DPOL and gB gene region, respectively. This indicated that although the HVs identified in our study could be classified in the same genus with other published bat HVs, their relationship might be phylogenetically distinct.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that 73 isolates of bat HVs, based on DPOL amino acid analysis, belonged to the subfamilies Betaherpesvirinae or Gammaherpesvirinae. No viruses of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae were found in our study. This might be due to low prevalence or viral loads of Alphaherpesvirinae members in fecal samples of bats. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue.

The diversity of Gammaherpesvirinae members found in bats is considerable. Viruses from different Gammaherpesvirinae genera appear to be circulating in all bat species. No significant phylogenetic clustering of viruses could be found on any single sampling occasion. In addition, viruses detected in the same bat species at the same time were still be genetically diverse, since HVs detected in Scotophilus kuhlii in Yunfu belonged to different genera of the Gammaherpesvirinae, namely, Percavirus, Lymphocryptovirus and Macavirus. Moreover, low DPOL amino acid pairwise similarities of HVs were found within a single bat species (i.e., Cynopterus sphinx in Guangzhou and Rhinolophus blythi and Scotophilus kuhlii in Yunfu), ranging from 27.8 % to 100.0 %, with an average of 71.1 %, 37.9 % and 40.5 %, respectively, which was consistently lower than 90 %.

HVs are generally species specific; however, in rare cases, interspecies transmission has been reported [19]. BOHV6 from the genus Macavirus was found to be related to bat HVs SK/11HZ85, CS/13HN70 and RB/13YF87, with 98.3-100 % sequence identity in the DPOL region and 100 % in the gB region, suggesting potential interspecies transmissions and a broad host range of bovine HVs. However, it would be challenging to determine the transmission route between two different animal species from remote geographic regions. Further studies of bovine-HVs and bat-HV from the same region are needed to test this hypothesis.

The mode of transmission of HVs in bats is unclear. Previous studies showed that HVs could be detected in fecal samples and anal swabs [10, 13]. Our results revealed that eight species of bats could harbor HVs in the digestive tract or shed viruses into their feces, with detection rates of 3.47 % to 33.33 %. These results suggest that the oral-fecal route is important for transmission of HVs in bats.

Based on the results of previous reports and the present study, we speculate that co-evolution has occurred between HVs and bats. This is based on the following evidence: 1) High prevalence rates of HVs were found in a variety of bat species from different geographic regions. 2) The bats carrying HVs seemed to show no overt signs of disease. 3) HVs showed significant genetic diversity among different bat species. Further studies that include more-detailed genomic sequence information of HVs from bats, coupled with sufficient epidemiological evidence, might offer greater insights into the role of HVs in bats.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

E-supplement 1: E-Figure 1. Geographical distribution of bats sampled in southern China. Triangles indicate the sampling locations. (JPEG 66 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wei-jie Guan (State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Disease) and Jin-ming Li (Department of Bioinformatics, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Southern Medical University) for their linguistic consideration and insightful suggestions. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30972525).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Shi Z. Bat and virus. Protein Cell. 2010;1(2):109–114. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calisher CH, Childs JE, Field HE, Holmes KV, Schountz T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miia JV, Tiina N, Tarja S, Olli V, Liisa S, Anita H. Evolutionary trends of European bat lyssavirus type 2 including genetic characterization of Finnish strains of human and bat origin 24 years apart. Arch Virol. 2015;160(6):1489–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2424-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Li X, Chen Z, Chen Z, Zhang Q, Liao Y, et al. Comparison of genomic and amino acid sequences of eight Japanese encephalitis virus isolates from bats. Arch Virol. 2013;158(12):2543–2552. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anindita PD, Sasaki M, Setiyono A, Handharyani E, Orba Y, Kobayashi S, et al. Arch Virol. 2015;160(4):1113–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehlers B. Discovery of herpesviruses. In: Mahy B, Van Regenmortel M, editors. Encyclopedia of virology. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wibbelt G, Kurth A, Yasmum N, Bannert M, Nagel S, Nitsche A, et al. Discovery of herpesviruses in bats. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2651–2655. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sano K, Okazaki S, Taniguchi S, Masangkay JS, Puentespina R, Jr, Eres E. Detection of a novel herpesvirus from bats in the Philippines. Virus Genes: DOI; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razafindratsimandresy R, Jeanmaire EM, Counor D, Vasconcelos PF, Sall AA, Reynes JM. Partial molecular characterization of alphaherpesviruses isolated from tropical bats. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:44–47. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.006825-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janoska M, Vidovszky M, Molnár V, Liptovszky M, Harrach B, Benko M. Novel adenoviruses and herpesviruses detected in bats. Vet J. 2011;189:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasaki M, Setiyono A, Handharyani E, Kobayashi S, Rahmadani I, Taha S, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel alphaherpesvirus in fruit bats. J Virol. 2014;88:9819–9829. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01277-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe S, Maeda K, Suzuki K, Ueda N, Iha K, Taniguchi S, et al. Novel betaherpesvirus in bats. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:986–988. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.091567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, Ren X, Yang L, Hu Y, Yang J, He G, et al. Virome analysis for identification of novel mammalian viruses in bat species from Chinese provinces. J Virol. 2012;86:10999–11012. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poon LL, Chu DK, Chan KH, Wong OK, Ellis TM, Leung YH, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in bats. J Virol. 2005;79:2001–2009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2001-2009.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linacre A, Lee JC. Species determination: the role and use of the cytochrome b gene. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;297:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Devanter DR, Warrener P, Bennett L, Schultz ER, Coulter S, Garber RL, Rose TM. Detection and analysis of diverse herpesviral species by consensus primer PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1666–1671. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1666-1671.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wozniakowski G, Samorek-Salamonowicz E. Animal herpesviruses and their zoonotic potential for cross-species infection. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22(2):191–194. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1152063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

E-supplement 1: E-Figure 1. Geographical distribution of bats sampled in southern China. Triangles indicate the sampling locations. (JPEG 66 kb)