Abstract

Multi-dimensional, multi-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become increasingly available for comprehensive and time-efficient evaluation of various pathologies, providing large amounts of data and offering new opportunities for improved image reconstructions. Recently, a cardiac phase-resolved myocardial T1 mapping method has been introduced to provide dynamic information on tissue viability. Improved spatio-temporal resolution in clinically acceptable scan times is highly desirable but requires high acceleration factors. Tensors are well-suited to describe inter-dimensional hidden structures in such multi-dimensional datasets. In this study, we sought to utilize and compare different tensor decomposition methods, without the use of auxiliary navigator data. We explored multiple processing approaches in order to enable high-resolution cardiac phase-resolved myocardial T1 mapping. Eight different low-rank tensor approximation and processing approaches were evaluated using quantitative analysis of accuracy and precision in T1 maps acquired in six healthy volunteers. All methods provided comparable T1 values. However, the precision was significantly improved using local processing, as well as a direct tensor rank approximation. Low-rank tensor approximation approaches are well-suited to enable dynamic T1 mapping at high spatio-temporal resolutions.

Index Terms—: Accelerated imaging, multi-dimensional MRI, myocardial T1 mapping, tensor processing, low-rank tensors, PARAFAC, Tucker

I. Introduction

Recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) facilitated the acquisition of large amounts of imaging data with various properties in single acquisitions, enabling multi-dimensional MRI [1–4]. In cardiac MRI, these techniques have demonstrated promise by acquiring two or three spatial dimensions in the presence of cardiac and/or respiratory motion [5–11]. Additionally, varying contrast weightings can be acquired for myocardial parametric mapping, including cardiac phase-resolved T1 mapping [7] and a recent approach called CMR multitasking [5, 11]. Such datasets are naturally n-dimensional, with n ≥ 4, and have ≥ 2 non-spatial (e.g., motion, contrast) dimensions. High acceleration factors are required to maintain clinically acceptable scan times for such multi-dimensional datasets, as the number of k-space encodings at the Nyquist rate grows exponentially with dimensionality [1].

A number of methods are available for accelerated MRI. Parallel imaging with uniform undersampling remains the most commonly used accelerated imaging approach [12, 13], even though it suffers from noise amplification at high acceleration rates. Compressed sensing, which exploits compressibility of data in transform domains and requires random under-sampling, has been extensively used with various transforms [14–20]. For MRI data consisting of an image series, low-rank matrix regularization has also been commonly utilized [21–25]. These methods exploit the correlations in the image series, by vectorizing each image in the series and utilizing the low-rank property of the resulting Casorati matrix [26–28]. The low-rank structure can be imposed either in a data-driven manner through nuclear norm minimization [21, 29] or through explicit estimation of subspace structures using an auxiliary, typically navigator-based, dataset [24, 26]. Low-rank matrix structure has also been used in conjunction with sparsity and other regularizers [21, 22]. Furthermore, these have been applied in a local manner, where patches extracted from the dataset were used to form local Casorati matrices, in order to reduce residual artifacts [28, 30]. Additionally, low-rank matrix methods have been used subsequent to parallel imaging as post processing in order to mitigate noise amplification, with the advantage of being easily compatible with clinical scan protocols [31–33].

While compressed sensing and low-rank matrix methods can also be applied to multi-dimensional MRI described earlier, such datasets may be better described with low-rank tensors [1, 34]. Tensors are able to describe multi-linear latent structures beyond the pairwise interactions captured by matrices [35]. So far, most of the tensor methods in multi-dimensional MRI have been based on a higher-order singular value decomposition for which subspaces have been explicitly estimated using auxiliary data [1, 5, 11, 36]. Furthermore, most tensor regularization methods used in MRI so far have relied on global processing of the whole multi-dimensional array [1, 5, 37–39] and the few works that have used local processing of tensors did not report advantages with respect to global processing [34]. However, as with low-rank matrix methods, global processing treats multiple tissues of different types jointly, which may lead to residual artifacts that can be ameliorated with local processing [28, 30].

In this work, we sought to utilize and compare different tensor decomposition methods, without the use of auxiliary navigator data, as well as multiple processing approaches in order to enable high-resolution cardiac phase-resolved myocardial T1 mapping. Myocardial T1 mapping has shown great clinical utility in numerous cardiomyopathies [40], but conventional sequences [41–44] have limited temporal resolution. A recently proposed technique, called temporally resolved parametric assessment of Z-magnetization recovery (TOPAZ), enables T1 mapping at high-temporal resolution [7], potentially facilitating quantification of mobile structures. However, this technique is performed in a single breath-hold which consequently brings about several limitations. The intrinsically limited scan duration requires a trade-off between signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution [45]. However, higher resolutions are highly desirable in order to better delineate the tissue borders and detect highly mobile structures. This can be achieved by further sub-sampling the acquisition, which can still be reconstructed by parallel imaging techniques, albeit at a higher noise amplification. Our aim is to use low-rank tensor methods for denoising such reconstructions in order to improve the precision of T1 maps. To this end, this paper presents the TOPAZ data model, an overview of low-rank tensor approximation (LRTA) methods for these acquisitions, followed by the different processing approaches that were studied, in Section II. Section III describes the imaging protocol, experiments, and quantitative analysis used in this study. Results are detailed in Section IV. Section V and VI provide a discussion and the conclusion.

II. Low-Rank Tensors for Dynamic T1 Mapping

A. Data Model in TOPAZ

In this study, a recently proposed MRI sequence [7] was used for cardiac phase-resolved quantification of the myocardial T1 time. The underlying imaging datasets, m(x, y, t, c), acquired with this sequence are 4-dimensional, where (x, y) are the spatial dimensions, t is the cardiac phase and c represents different T1 contrasts. The corresponding k-space acquisition is given as

| (1) |

where Et,c: is the encoding operator, including a partial Fourier matrix and the sensitivities of the receiver coil array, is measurement noise, and x, y, t, c are as described above. Data was acquired with uniform undersampling since our clinical workflow uses this type of undersampling with GRAPPA reconstructions. Subsequently, y(t, c) was used to generate via GRAPPA [13] and SENSE-1 combination of the reconstructed coil images [12, 46]. SENSE-1 combination is advantageous, as it is a linear operation, and it has been shown to reduce issues related to background noise in root-sum-squares images [46]. We note that the reconstruction noise in is typically modeled as Gaussian, since the GRAPPA reconstruction is also commonly modeled as a linear operation [47]. However, there may be factors, such as noise in the ACS data, which might introduce nonlinearities during reconstruction, although these effects are typically observed only at low SNR regimes [48]. In this study, the nonlinearities in the GRAPPA reconstruction were not considered, and the reconstruction noise was modeled as Gaussian, as is conventionally done [47]. Various tensor decompositions were applied to these image series to reduce noise amplification arising from GRAPPA.

B. PARAFAC Decomposition

PARAFAC tensor decomposition, as illustrated in Figure 1a, is a direct rank decomposition method that uniquely factorizes a tensor into a sum of rank-one tensors. Low-rank approximation based on PARAFAC in this context is given as

| (2) |

where ‖ · ‖F is the Frobenius norm, R is the rank of the low-rank tensor and ⊚ is the outer product given as

| (3) |

Fig. 1:

a) PARAFAC decomposes a tensor into sum of rank one tensors. b) Tucker decomposes a tensor into a core tensor multiplied with factor matrices along each mode. Note a 3D tensor is shown for illustration purposes.

We note that while the formulation in Equation (2) is a denoising formulation, it does not have a maximum likelihood interpretation, as the covariance matrix of the reconstructed noise in individual images is not proportional to the identity matrix. The characteristics of the covariance matrix are further discussed in Section V.

Factor matrices of rank-one components of the tensor [49] are represented as A = [a1, a2, …, aR], B = [b1, b2, …, bR], C = [c1, c2, … , cR], and D = [d1, d2, … , dR].

The tensor, m can be unfolded into a matrix representation along mode k ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4} by considering the kth mode as one dimension of a matrix and combining the other modes into the other dimension of that matrix. For the jth element in the kth mode, the corresponding elements in the tensor forms a “slab,” which is vectorized and treated as the jth column of the unfolded matrix along mode k. Applying this to the representation in Equation (3), we obtain the matrix unfolding along the first mode as

| (4) |

as well as X2 = (D ⊙ B ⊙ A)CT , X3 = (D ⊙ C ⊙ A)BT, and X4 = (D ⊙ C ⊙ B)AT as unfoldings along modes 2, 3 and 4 respectively. Here ⊙ represents the Khatri-Rao product, which corresponds to column-wise Kronecker products for two matrices with the same number of columns [49] and T denotes the transpose opearation. The use of matrix unfoldings allows restating Equation (2) as

| (5) |

This problem is a non-linear and non-convex least squares problem. However, an approximate solution can be obtained using an alternating least squares (ALS) method [49, 50]. ALS approaches the non-convex least squares problem using a sequence of linear least squares problems by fixing all matrices except one of them at every iteration. At iteration t, this leads to the following updates for each of the factor matrices

where the superscript (t) denotes the estimate at iteration t. The procedure is repeated until a stopping criterion is satisfied.

C. Tucker Decomposition

Tucker decomposition is a form of higher order singular value decomposition (SVD) method [49]. It decomposes a tensor into a core tensor with a matrix multiplied along each mode which is similar to SVD of matrices, as depicted in Figure 1b. For our problem, low-rank approximation based on Tucker decomposition for the 4-D tensor, is given as

| (6) |

where , , , are unitary factor matrices obtained through principal components along corresponding modes and is the core tensor whose elements show the level of interaction among modes. The above optimization can be posed in terms of matrix unfoldings similar to the PARAFAC case by using unfolding along any chosen mode. Without loss of generality, one can unfold the matrix along mode 1, yielding

| (7) |

where ⊗ is the Kronecker product and G1 is a matrix unfolding of the core tensor along mode 1. The above non-convex problem is solved using ALS approach which fixes all components except the one to be updated as in PARAFAC. U, V, W, Z are initialized by r1, r2, r3, r4 principal right singular vectors of the matrix unfoldings X1, X2, X3, X4, respectively. Afterwards, the ALS update is performed for each factor matrices as follows [49]

where * is the conjugate operation, H is the conjugate transpose, and keeps the k principal right singular vectors of its argument. The procedure is repeated until a convergence criterion is satisfied. As in Section II-B, the formulation in Equation (6) does not have a maximum likelihood interpretation, which is further discussed in Section V.

D. LRTA Processing Approaches

For both tensor decompositions, there are several options of processing the multi-dimensional MRI data. The processing approaches considered in this study are detailed next.

1). Global and Local LRTA:

LRTA for MRI has been studied from a global perspective, where the dataset is processed in a volumetric manner [1, 34, 37–39]. This approach processes various tissues and structures with distinct functional and T1 properties. For instance, the chest wall and back contain stationary tissue with short T1 (< 250 ms), while the myocardium moves substantially through the cardiac cycle and has a longer T1 (~ 1400 – 1500 ms at 3T) [51]. Such variation impedes capturing all the information in the volume by LRTA. Thus, as in the low-rank matrix regularization setting, it may be beneficial to process the data locally, which was explored in our earlier work for PARAFAC decomposition [52]. Local processing allows processing of small areas, which are likely to contain similar tissue types and functional properties, allowing for efficient low-rank representations. In this work, we implement this strategy for both decompositions, and perform LRTA over small patches in the spatial x-y domain. Locally low-rank processing for noisy tensor was implemented by extracting 8 × 8 × T × C patches from imaging dataset which were processed as a 4-dimensional tensor. This operation is performed by applying a patch extractor operator, Γ on the noisy tensor , i.e. , where pϕ is the extracted patch, ϕ ∈ {1, … , Φ} and Φ is the total number of patches. Then for each extracted patch pϕ, the following objective function was solved for PARAFAC decomposition via previously described ALS

while for Tucker decomposition, the objective function was

| (8) |

Overlapping patches were used with a stride of four, which were combined via averaging after processing.

2). 3D and 4D LRTA:

TOPAZ data is inherently 4D in nature, as described in Section II-A. Two of these dimensions correspond to spatial x-y coordinates. These spatial dimensions contain structures such as tissue borders, which include features such as edges and curves, which are not necessarily amenable to low-rank tensor decompositions [53]. Thus, as an alternative processing approach, we also investigated the use of vectorizing the spatial dimensions of the whole volume and patches. This approach is in-line with previous low-rank matrix regularization literature [26–28]. Vectorization yields 3D tensors, with one dimension capturing the spatial dimensions, and the other two representing cardiac phase and T1 weights. Additionally, this 3D approach was combined with global and local processing, by vectorizing the corresponding spatial dimensions. In local processing, this vectorization of the 4D 8 × 8 × T × C patches yields 64 × T × C 3D patches. More formally, following objective functions were solved using ALS for each vectorized extracted patch, for PARAFAC decomposition as

and for Tucker decomposition as

| (9) |

As in local LRTA approach, overlapping patches were combined via averaging after processing.

E. Rank Selection

Rank is an important hyperparameter for LRTA approaches. While insufficient tensor rank may bias the T1 measurements or lead to blurring artifacts, high values lead to limited noise reduction. Furthermore, the rank needs to be pre-specified before running the ALS algorithm. To date there is no standard way of selecting appropriate tensor rank. In fact, even determining the rank of the noisy tensor, , is an NP-hard problem [49]. In this study, we perform empirical rank selection for global, global-3D, local and local-3D PARAFAC LRTA. Tensor ranks of {100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600}, {5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30}, {10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 100} and {7, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30} were used in Equation (2), for the four methods, respectively. Evaluation was performed both visually and quantitatively on T1 maps. These empirically selected ranks were fixed for the remainder of the study for the respective processing approaches.

For Tucker decomposition, empirical selection of the multi-linear rank (r1, r2, r3, r4) or (r1, r2, r3) is challenging due to the high degrees of freedom arising from its multi-linear nature. Hence, in this case instead of optimizing the rank of each mode, we optimized the proportion of the sum of singular values retained by keeping the rk principal singular values of the corresponding matrix unfoldings and truncating the rest. Thus, the following ratio was used for thresholding

| (10) |

where σi is the ith largest singular value of the relevant matrix unfolding, d is the total number of singular values, and l is the rank choice. We note that the ranks for each unfolding are allowed to differ, i.e l varies with the corresponding mode. A threshold 0 < ρ < 1 was used to select the largest l such that Ψ(l) was < ρ for all matrix unfoldings. Thresholds of ρ ∈ {.60, .70, .80, .90} for local, local-3D, global and global-3D LRTA methods were empirically evaluated. Visual and quantitative evaluations of the T1 time in a sub-cohort were employed to determine ranks, which were then fixed for the remainder of the study.

III. Methods

A. In Vivo Imaging

The imaging protocol was approved by the local institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before each examination for this HIPAA-compliant study. Cardiac phase-resolved T1 maps were obtained from six healthy subjects (three males, 39±18 years). All imaging was performed at a 3T Siemens Magnetom Prisma (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using a 30-channel receiver coil-array. Imaging sequence parameters used in this study were as follows: TR/TE /flip angle = 5/2.5 ms/3°, bandwidth = 350 Hz/Px, field of view (FOV) = 300 × 225 mm2, spatial resolution = 1.3 × 1.3 mm2, slice thickness = 10mm, partial Fourier=6/8, GRAPPA factor = 3, reference lines = 24 (in plane), time between inversion pules = 5 to 6 R-R intervals (heart-rate dependent [7]), temporal resolution = 60 ms, breath-hold duration = 17–20 s. Here, temporal resolution refers to the duration of a cardiac phase. Across all subjects, on average, the sequence had 13.33 cardiac phases and 5.16 inversion times per acquisition leading to a total of 64.83 images. Images were also acquired at a lower spatial resolution of 1.9 × 1.9 mm2 and GRAPPA factor = 2, with the rest of the other acquisition parameters unchanged, to serve as the reference for estimated T1 values. All images were acquired in a single mid-ventricular short-axis slice.

B. Comparison of LRTA Approaches

Three sets of comparisons were performed in this study:

Effect of tensor decomposition (PARAFAC and Tucker)

Effect of global and local LRTA processing

Effect of 3D and 4D LRTA processing

A total of eight LRTA approaches were evaluated, namely PARAFAC and Tucker decompositions, each with global, global-3D, local and local-3D processing. All methods were implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) on a conventional desktop workstation with a 3.4-GHz central processing and 16 GB random-access memory.

C. Quantitative T1 Mapping and Statistical Analysis

Quantitative T1 maps were used to evaluate the performance of the LRTA methods. The magnetization during TOPAZ T1 mapping sequence is described with a three-parameter model,

| (11) |

where is the inversion time of the kth T1- weighted image of the jth cardiac phase, is the corresponding signal for a given pixel location, A is the steady-state gradient echo magnetization, B is the inversion efficiency, and is the apparent T1, which is a function of the T1, flip angle α, and TR [54]. Due to inhomogeneities, α varies across the imaging FOV. Thus, in order to accurately derive T1 from , a correction strategy was proposed in [7], which was also used in this study. Following this three-parameter fitting with correction, myocardial T1 times were assessed throughout the R-R interval. Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually drawn, delineating endocardial and epicardial contours for each cardiac phase. For a given cardiac phase, the estimated T1 value and T1 precision were respectively defined as the mean and standard deviation of the T1 values within the ROI. For a given subject, the overall T1 and precision were reported as the respective quantities averaged across all cardiac phases, as mean ± standard deviation.

Several statistical comparisons were performed to identify differences between the LRTA methods. Average T1 times were compared among the LRTA methods using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The lower 1.9 × 1.9 mm2 resolution acquisition as in [7] was used as the reference for the estimated T1 times. Precision values were statistically evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis tests, which was followed by pair-wise Mann-Whitney U tests in case of significant differences between the LRTA methods. Additionally intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was measured based on a mean rating, absolute-agreement and 2-way mixed effects model. ICC values ≥0.75 were considered to show good agreement between methods, while those <0.75 were deemed as an indication of significant statistical difference between compared pairs [55]. Group tests were considered significant for p-values < 0.05. Bonferroni correction was performed to account for multiple comparisons for the pairwise testing. Thus, Mann-Whitney U tests had a Bonferroni-corrected type-I error of 0.001 (0.05 divided by 36 comparisons).

IV. RESULTS

A. Effect of Tensor Rank Selection

Figure 2a depicts example T1 maps used for empirical choice of the tensor rank hyperparameter for PARAFAC approximation. A representative end-diastolic phase is shown. Spatial blurring in the blood-myocardium border was visible for the global approach for tensor ranks below 300. Higher rank reduced visual apparent blurring, albeit at an increased noise level. On the other hand, global-3D processing was robust to spatial blurring at the observed ranks. Similarly, no spatial blurring was apparent among the studied ranks for either of the local processing approaches, as the small patches contained features with similar functional or contrast properties, which were well represented by low-rank tensors. The quantitative data for T1 values and T1 precision are depicted in Figure 2b, and are in good agreement with the visual assessment. Average T1 values closely matched the reference T1 value of 1357±22 ms from the low resolution reference, at ranks for which there were no apparent blurring artifacts. A mismatch between the T1 estimates was apparent for rank values in the range of 100 to 500 and 5 to 15 in the global and global-3D PARAFAC approaches, respectively. On the other hand, local and local-3D processing approaches are in good agreement with the reference across all ranks. For all processing approaches, precision degraded with increasing rank. Based on this data, ranks of 600 and 20 were chosen as optimal for the global and global-3D PARAFAC approaches respectively, whereas ranks of 10 and 7 were chosen for the local and local-3D PARAFAC approaches respectively, which were used for the remainder of the experiments.

Fig. 2:

a) T1 maps of a representative end-diastolic cardiac phase for global, global-3D, local and local-3D PARAFAC approximation for various ranks together with reference mean low-resolution data T1 value (dashed line). Global PARAFAC exhibits blurring artifacts for low ranks, whereas global-3D and local PARAFAC approaches do not suffer from these artifacts at low ranks. The amount of noise increases as rank increases in all approaches. b) The quantitative metrics confirm the visual observations in (a), where precision degrades with increasing rank (bottom). Local PARAFAC approaches yield similar T1 values to the reference across observed ranks (top), but global PARAFAC approaches misestimate the T1 value with respect to low-resolution data for low tensor ranks.

Figure 3 illustrates the empirical rank selection for Tucker approximation for the same subject in Figure 2. The global and local Tucker LRTA approaches were adversely affected by spatial blurring for thresholds ≤.80 as apparent in the quantitative T1 maps depicted in Figure 3a. Global-3D and local-3D Tucker LRTA approaches suffered from spatial blurring for thresholds of ≤.70. Higher thresholds ameliorated these blurring artifacts, albeit at a trade-off in noise amplification, similar to the PARAFAC decomposition. Figure 3b depicts the quantitative data for average T1 times and precision. Both global Tucker approaches showed considerably increased T1 times for thresholds ≤.80 compared with the average T1 value of the low resolution data. For local and local-3D Tucker LRTA approaches, mismatch in T1 values were observed at thresholds ≤ 80 and ≤.70, respectively. Accordingly, a threshold of .90 was chosen for global, global-3D and local Tucker LRTA approaches, respectively, and a threshold of .80 was chosen for local-3D Tucker approach based on the visual and quantitative assessments.

Fig. 3:

a) T1 maps of a representative end-diastolic cardiac phase for global, global-3D, local and local-3D Tucker approximation for various thresholds. Global and local Tucker techniques display blurring artifacts for thresholds ≤.80, while global-3D and local-3D Tucker approaches also exhibit blurring artifacts at thresholds ≤.70. Blurring artifacts are eliminated for higher threshold in all approaches, albeit at a trade-off in noise in the T1 maps. b) The quantitative metrics for Tucker approximations are in agreement with the visual observations from (a). Global, global-3D and local Tucker LRTA misestimate the T1 values for thresholds ≤.80, while local-3D Tucker methods show bias for threshold ≤.70 with respect to low-resolution data. As threshold increases, average T1 estimates of Tucker LRTA methods reaches a good agreement with low-resolution data, while the precision values generally degrade.

B. Comparison of LRTA Approaches

Figure 4 depicts representative dynamic quantitative T1 maps from a healthy subject using global LRTA approaches. The GRAPPA reconstruction shows major noise variations at this high resolution, due to lower signal-to-noise in the imaging data. The average T1 and precision values assessed accross the cardiac phases were 1460±39 ms and 310±27 ms for GRAPPA, while the corresponding values for the low-resolution reference were 1452±20 ms and 126±35 ms, respectively. All global LRTA approaches achieved T1 times that are in good agreement with the low-resolution data (1461±32 ms and 1466±37 ms for global and global-3D PARAFAC; 1465±40 ms, 1463±36 ms for global and global-3D Tucker), while visibly reducing noise observed in GRAPPA. Global and global-3D PARAFAC LRTA method achieved improved precision of 191±21 ms and 198±23 ms compared with GRAPPA. However, residual artifacts remained visible, including signal contamination from blood pools in the earlier phases, mostly in the inferior and lateral segments, as well as residual inhomogeneity in the myocardium in the later cardiac phases. Comparable trends were observed for global and global-3D Tucker LRTA approaches, which led to precisions of 205±20 ms and 229±32 ms respectively, with some residual artifacts, such as visible signal inhomogeneity in later cardiac phases.

Fig. 4:

Dynamic quantitative T1 maps from a healthy subject using GRAPPA, and the global PARAFAC and Tucker LRTA processing approaches. T1 maps of six cardiac phases equally spaced across the R-R interval are shown. Global and global-3D PARAFAC and Tucker approaches mitigate noise amplification compared to GRAPPA, but residual artifacts such as signal inhomogeneity in later cardiac phases remained visible. Overall precision of the myocardial T1 values for this subject across all cardiac phases were 191±21 ms and 198±23 ms for global and global-3D PARAFAC, and were 205±20 ms and 229±32 ms for global and global-3D Tucker LRTA approaches respectively.

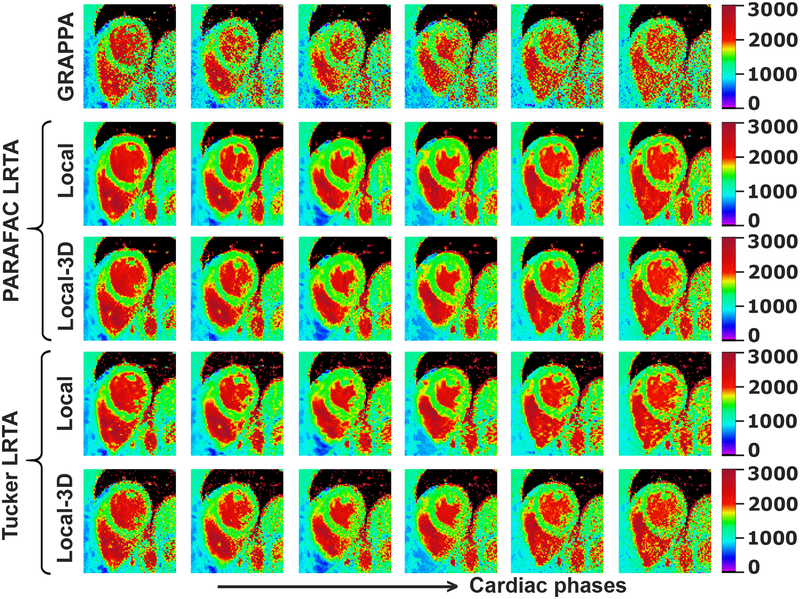

Figure 5 depicts representative dynamic quantitative T1 maps for the same subject using local LRTA approaches. As in global LRTA approaches, all local LRTA methods achieved T1 times that were in good agreement with baseline low-resolution images. These local LRTA techniques further suppressed the residual artifacts in global LRTA approaches and improved the quality of the T1 maps compared to their global LRTA counterparts. The local LRTA improvements over GRAPPA and global LRTA methods were also observed quantitatively. The precision values were 122±20 ms and 127±19 ms for local and local-3D PARAFAC LRTA and were 147±23 ms and 179±27 ms for local and local-3D Tucker LRTA approaches, respectively.

Fig. 5:

Dynamic quantitative T1 maps for the same subject in Figure 4, reconstructed using GRAPPA, and the local PARAFAC and Tucker LRTA processing approaches. T1 maps of six cardiac phases equally spaced across the R-R interval are shown. For both PARAFAC and Tucker decompositions, local LRTA methods significantly mitigate noise amplification, while eliminating residual artifacts that affect the inferior segment, especially in end diastolic phases, when using the global LRTA approaches. Overall precision of the myocardial T1 values for this subject across all cardiac phases were 122±20 ms and 127±19 ms for local and local-3D PARAFAC LRTA and were 147±23 ms and 179±27 ms for local and local-3D Tucker LRTA approaches, respectively..

Compared with PARAFAC LRTA, Tucker LRTA resulted in slightly increased noise variation, especially in the later cardiac phases. We also note that the noise performance degraded in the later cardiac phases for all methods, because of the smaller amount of magnetization changes for the T1 parameter estimation in these phases, as a result of the corresponding long effective inversion times [7].

Figure 6 depicts representative systolic cardiac phase T1 maps for all subjects, using all the LRTA techniques. In all subjects, global LRTA methods alleviated the noise amplification in GRAPPA, but residual artifacts such as blood contamination were observed. These were further ameliorated with the local LRTA approaches. Comparable trends were observed in each method among all subjects.

Fig. 6:

Representative systolic cardiac phase T1 maps for all subjects, reconstructed using GRAPPA, and PARAFAC and Tucker LRTA processing approaches. Similar improvements to those in Figures 4 and 5 were observed in each LRTA method for all subjects.

T1 values through the cardiac phases for a cross-section of the heart are depicted in Figure 7 for a representative subject. In both PARAFAC and Tucker LRTA methods, functional representation of cardiac motion did not suffer from apparent temporal blurring, indicating that functional information is preserved through the cardiac cycle. There was visible improvement in delineation of the tissue borders using the LRTA approaches over GRAPPA, which suffered from high noise amplification.

Fig. 7:

T1 times throughout cardiac phases across a cross-section of the heart for one of the subjects. GRAPPA suffers from substantial noise amplification, making it difficult to identify tissue borders. The T1 maps generated using the LRTA methods significantly decrease these noise artifacts, while not hindering identification of tissue borders.

Table I lists the average T1 time and precision across all six subjects and all cardiac phases for the reference low-resolution acquisition and the LRTA methods applied on the higher resolution data. Group analysis of the mean T1 values from LRTA methods and low-resolution reference showed no statistical difference (p = 0.62).

TABLE I:

The average T1 time and precision values across all six subjects and all cardiac phases.

| PARAFAC | Tucker | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-resolution Reference | GRAPPA(R3) | Global | Global-3D | Local | Local-3D | Global | Global-3D | Local | Local-3D | |

| Average T1 time | 1420 ± 60 ms | 1428 ±60 ms | 1434 ± 60 ms | 1435 ± 54 ms | 1424 ± 51ms | 1428 ± 53 ms | 1428 ± 55 ms | 1431 ± 55 ms | 1430 ± 58 ms | 1436 ± 53 ms |

| Precision | 137 ± 57 ms | 331 ± 69 ms | 193 ± 34 ms | 218 ± 53 ms | 124± 24 ms | 132 ± 25 ms | 204 ± 51 ms | 256 ± 73 ms | 162 ± 41 ms | 195 ± 40 ms |

Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed statistical differences in precision among the methods (p < 10−10). A box-plot showing the median and spread of the precision data is shown in Figure 8a. This visualization suggests that local and local-3D LRTA methods have similar performance for each of the PARAFAC and Tucker decompositions, while they outperform their global counterparts.

Fig. 8:

a) Box plot showing the median and spread of the precision data for each LRTA method. Kruskal-Wallis analysis showed significant differences among the methods with a p-value < 10−10. b) Results of the pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests and ICC are displayed in a graph. There are statistically significant differences among most pairs of methods, except the methods sharing the red edges. The ICC and p-values between two methods are shown next to the edge that connects them for the red edges only for improved readability.

The results of the pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests and ICC for each possible processing pair are depicted in Figure 8b using a graph representation. Edges in red indicate non-significant differences, while gray edges show statistically significant differences (p < 0.001 and ICC < 0.75). The ICC and p-values are also depicted next to the edge for non-significant differences, while they are not shown for significant differences for increased readability. Thus, the best precision performance was achieved by local PARAFAC method, which was statistically similar to local-3D PARAFAC, but statistically improved compared to global and global-3D PARAFAC methods which also showed similar statistical manner with each other. PARAFAC global-3D showed similar statistical behavior with Tucker global, global-3D and local-3D LRTA approaches, while global and local-3D Tucker approaches were the only pair within Tucker methods showing similar statistical behaviour. The remaining approaches were statistically different. In both PARAFAC and Tucker LRTA methods, local processing outperforms local-3D, while global processing outperforms global-3D. All methods improved precision compared to the GRAPPA reconstruction of the high-resolution data in a statistically significant manner.

V. Discussion

In this study, we investigated PARAFAC and Tucker low-rank tensor approximation techniques for multi-dimensional MRI datasets. These techniques were applied to high-resolution dynamic cardiac T1 mapping acquisitions [7]. For both PARAFAC and Tucker decompositions, global, global-3D, local and local-3D LRTA processing approaches were studied. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multi-dimensional MRI study that quantitatively evaluates different tensor decompositions and processing approaches for a total of 8 comparisons. Thus, as multi-dimensional MRI continues to grow rapidly, such a detailed and thorough evaluation may provide guidelines for designing low-rank tensor reconstruction and denoising algorithms for these datasets. Furthermore, the proposed tensor approximation in conjunction with the accelerated acquisition of rate 3 considered here enables dynamic myocardial T1 mapping with a spatial resolution of 1.3 × 1.3 mm2 and temporal resolution of 60 ms. Previously reported resolutions for this approach were confined to spatial resolutions of 1.9 × 1.9 mm2 [7]. Additionally, most conventional myocardial T1 methods exhibit a temporal resolution of 200–250 ms [40] for a single cardiac phase. These improvements in resolutions may facilitate better delineation of blood-myocardium border, reducing partial voluming artifacts and characterize highly mobile structures such as the papillary muscles. Thus, further clinical studies to understand additional benefits of the improved resolution are warranted.

All LRTA approaches showed significant noise reduction compared with the GRAPPA reconstruction in the high-resolution low-SNR regime. For both tensor decompositions, the local processing approaches outperformed global approaches, both visually and quantitatively. Thus, global tensor processing may not be an optimal approximation strategy for multi-dimensional MRI data, since the imaging field-of-view contains multiple structures with disparate functional and contrast properties. Local processing considers small patches that are likely to have structures with similar functional and contrast properties. This was shown to be a better fit in improving both the visual image quality and the quantitative metrics. Local processing also allows using smaller tensor ranks, since maximal rank grows proportionally with the product of the three smallest tensor dimensions. Besides the imaging improvement, local processing may have a computational advantage over global processing since the patches can be processed independently. This facilitates parallelization on multi-cores or GPU, although such gains were not explored. For the ranks used in this study, the runtimes per iteration for PARAFAC and Tucker were similar, with global processing taking approximately 30 seconds, global-3D taking approximately 1 second, and local and local-3D methods taking 10 seconds per iteration. We note that the runtimes are rank-dependent and increase with the rank, for instance as observed between global and global-3D LRTA approaches.

In local processing approaches for PARAFAC difference in terms of the visual quality and quantitative metric of local and local-3D LRTA approaches is small, and the differences were not statistically significant. This difference between local and local-3D LRTA was higher in Tucker, where results showed significant statistical differences. In both PARAFAC and Tucker approaches, local LRTA with 4D patches performed better than local LRTA with 3D patches in terms of precision. However, local-3D LRTA methods showed visually enhanced improvement in myocardium-blood boundary delineation compared to local approaches. Thus they may be preferable in cases where border sharpness is more important.

In terms of the comparisons posed in Section III-B, our findings on precision and quality of dynamic myocardial T1 maps can be summarized as follows: i) PARAFAC LRTA methods outperformed their Tucker counterparts both visually and quantitatively. Although for global-3D, the improvement was not statistically significant. ii) Local processing approaches outperformed their global processing counterparts in all cases. iii) Local (4D) approaches outperformed their local-3D counterparts in terms of quantification of precision, with a significant improvement for Tucker decomposition. However, local-3D approaches offered sharper delineation of myocardium-blood boundary in some subjects.

In this study, PARAFAC approximation methods outperformed the Tucker decomposition in terms of visual quality and quantitative metrics. One possible explanation for this difference in performance is related to the difference in the degrees of freedom. PARAFAC method is less susceptible to over-fitting issues since there is only one tensor rank parameter to be estimated. On the other hand, Tucker decomposition is a form of higher-order SVD. In SVD of matrices, the best low-rank approximation achieved with the Eckart-Young theorem is obtained by keeping few large eigenvalues and discarding the rest. Tucker decomposition follows a similar procedure with SVD by gathering slabs with highest energy from each mode and keeping them in a part of the core tensor, then truncating the rest. However, unlike SVD, Tucker does not end up with best low-rank tensor approximation since there is no equivalent form of the Eckart-Young theorem for tensors. Hence, the higher degrees of freedom in Tucker decomposition makes it susceptible to over-fitting. These differences between the two tensor decompositions are also appreciated in other fields. For instance, PARAFAC decomposition is used in latent signal estimation [56], whereas Tucker is often used for compression purposes such as face recognition [57].

Spatial variability of the myocardial T1 maps in an ROI, and the reproducibility of the mean T1 values in an ROI across multiple repeated experiments are commonly used as surrogates for precision in myocardial T1 mapping [58]. In this study, we used the spatial variability to characterize precision. The values reported here, even after the use of LRTA methods, are seemingly higher than the previously reported variation of T1 times across the cardiac cycle when using TOPAZ [7]. However, this is not a contradiction, since in clinical studies, it is common to perform analysis based on the estimated T1 values over an ROI [40]. After averaging, the differences of mean values across regions are generally smaller than the changes that needs to be detected. Lower spatial variability enables regions to be defined with fewer number of pixels, while allowing regional differences to be detected. This is important in disease populations, where different parts of the myocardium may have different T1 properties. Thus regional analysis with fewer number of pixels is often desirable, leading to our goal of improving spatial variability.

Many of the existing works that employed LRTA in MRI have focused on Tucker decomposition [1, 5, 36]. These works have so far utilized a subspace learning approach, where complementary navigator data is acquired to estimate the subspaces and their ranks for the non-spatial data dimensions. Hence, the implementation of these approaches require changes in the pulse sequence and acquisition. Therefore, these approaches were not investigated in our study, and instead a data-driven approach was used for Tucker decomposition. The use of navigator data as in [1, 5, 36] may further benefit the LRTA approaches considered here. Furthermore, these aforementioned previous works relied on global processing of the datasets. However, in our data-driven approach, significant improvement was shown using local LRTA processing. While our work focused on PARAFAC and Tucker decompositions, there are also other methods for LRTA [59, 60]. In these works, the summation of the ranks of the matrix unfoldings along each mode is considered as the objective function to minimize subject to data consistency terms, and was applied to tensor completion. However, the number of variables grows by the product of all dimensions, making it computationally expensive for large datasets. Additionally, regularizers on the tensor coefficients can be incorporated into the main objective function in order to penalize misrepresentations that may occur in some areas, such as background air region with no signal, where any non-zero tensor rank would lead to incorrect representations. As multi-dimensional MRI increasingly becomes utilized with novel acquisition approaches [1, 5, 7], a quantitative comparison of LRTA methods as in this study, may be instrumental in designing better reconstruction algorithms.

A limitation of LRTA methods relates to rank selection. Since determining the rank of a tensor is an NP-hard problem [50], empirical rank selection was used both in previous studies [1, 5, 36] and in this study. However, it is desirable to have a metric that unifies hyperparameter selection across decompositions. To this end, we have explored the normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE) of reconstructions as a possible candidate. While this provided similar ranges of thresholds across decompositions, it still required separate fine-tuning for using either local or global processing. Additionally, a threshold for this NRMSE metric still needs to be translated to rank hyperparameters in order to run the LRTA algorithms. A further complication for the Tucker model is that an NRMSE value can be achieved with different selection of ranks across modes, leading to non-uniqueness. Thus, we utilized rank-related hyperparameters for ease of algorithmic translation, even though it requires fine-tuning across different decompositions and processing techniques. In the data-driven approach considered here, a single tensor rank parameter was used for PARAFAC, whereas a single proportion involving the magnitude of the singular values of the matrix unfoldings was used for Tucker decompositions, leading to an adaptive selection of ranks. Due to the high number of degrees of freedom in Tucker decompositions, the same threshold parameter was utilized across all modes. Further gains may be possible by fine-tuning this parameter for individual modes. However, this was not explored due to the exhaustive search requirements, which would make such a selection difficult in practical scenarios.

As discussed in Sections II-B and II-C, the denoising formulations in Equations (2) and (6) do not have a maximum likelihood interpretation. While the noise in the reconstructed SENSE-1 images are Gaussian, they are not independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), i.e. the covariance matrix is not proportional to the identity matrix. While the computation of the covariance matrix is difficult, a better approximation may be possible via g-factor analysis [12, 47]. We further detail this formulation and related experiments in Appendix I, while noting that it did not lead to an improvement over the formulations stated in Equations (2) and (6) in our study. Another alternative for avoiding the non-i.i.d. Gaussian noise after GRAPPA reconstruction is to run an end-to-end inverse problem from k-space to image space. However, this comes at the cost of additional computational complexity of an iterative method and parameter tuning. This alternative is further detailed in Appendix II, although we note that this approach also did not lead to an improvement over the original formulation.

VI. Conclusion

We utilized and compared different tensor decomposition methods and multiple processing approaches to enable high-resolution cardiac phase-resolved myocardial T1 mapping. Tensor approximations were performed in a data-driven manner without auxiliary navigator data. Local tensor processing showed significant improvement over global processing, and PARAFAC decomposition led to improvements in precision over Tucker decomposition. The proposed techniques for LRTA enabled cardiac-phase resolved T1 mapping at 1.3 × 1.3 mm2 spatial and 60 ms temporal resolution, while maintaining clinical image quality and scan time.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH R00HL111410, NIH P41EB015894, NIH P41EB027061, NSF CAREER CCF-1651825 and NSF IIS-1704074.

Biographies

Burhaneddin Yaman received the B. Eng. degree from Istanbul Technical University (ITU), Istanbul, Turkey, in 2016. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. degree in Electrical Engineering at the University of Minnesota, MN, USA. His research interests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), tensor decompositions and machine learning.

Sebastian Weingärtner (M18) received the Dip.-Inform. (equivalent M.Sc. in Computer Science) from University of Wrzburg, Germany in 2010. From 2011 to 2014 he performed research at Harvard Medical School, MA, USA and Heidelberg University, Germany and obtained his Ph.D. in medical physics from Heidelberg University in 2015. He has been a post-doctoral fellow at Heidelberg University, University of Minnesota, MN, USA and Stanford University, CA, USA. He is currently an Assistant Professor, leading the Magnetic Resonance Systems (MARS) lab at Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands. His research interest includes quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging and development of MRI based imaging biomarkers. His work has received a number of recognitions.

Nikos Kargas received the Diploma and M.Sc. degrees in electronic and computer engineering from the Technical University of Crete (TUC), Greece, in 2013 and 2015, respectively. Since 2015, he has been working towards the Ph.D. degree in electrical and computer engineering at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. His research interests include signal processing, machine learning, and optimization.

Nicholas D. Sidiropoulos (F’09) received the Diploma degree in electrical engineering from Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, and the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineering from the University of Maryland-College Park, College Park, MD, USA, in 1988, 1990, and 1992, respectively. He has served on the faculty of the University of Virginia (UVA), University of Minnesota, and the Technical University of Crete, Greece, prior to his current appointment as Louis T. Rader Professor and Chair of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at UVA. His research interests are in signal processing, communications, optimization, tensor decomposition, and factor analysis, with applications in machine learning and communications. He received the NSF/CAREER award in 1998, the IEEE Signal Processing Society (SPS) Best Paper Award in 2001, 2007, and 2011, served as IEEE SPS Distinguished Lecturer (2008–2009), and currently serves as Vice President -Membership of IEEE SPS. He received the 2010 IEEE Signal Processing Society Meritorious Service Award, and the 2013 Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Maryland, Dept. of ECE. He is a Fellow of IEEE (2009) and a Fellow of EURASIP (2014).

Mehmet Akçakaya (M ‘10) received the B. Eng. degree with great distinction from McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, in 2005, and the S.M. and Ph.D. degrees from Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, in 2010. From 2010 to 2015, he was with the Harvard Medical School. He is currently a McKnight-Land Grant Assistant Professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. He holds an R00 Award from NIH and a CAREER Award from NSF. His work on accelerated MRI has received a number of international recognitions. His research interests include MRI reconstruction, cardiac MRI, machine learning, inverse problems and signal processing.

A. Appendix I

Let G be the GRAPPA operator and E* be the SENSE-1 coil combination operator. For i.i.d. acquisition noise, the noise in each of the reconstructed images in Equations (2) and (6) have covariance matrix proportional to K = E*GG*E. Calculation of this covariance matrix is not computationally straightforward. However, the square root of its diagonal entries can be approximated via g-factor analysis [12]. For the GRAPPA reconstruction used here, which involves a fully-sampled central k-space, pseudo-replica method [47] provides a method for approximating the g-factor maps.

To this end, 1000 runs of the pseudo-replica method were used to generate g-factor maps, . The g-factor maps were incorporated into objective function in Equation (2) as

| (12) |

and in Equation (6) as

| (13) |

These problems were solved for the same ranks as in the original formulations of Equations (2) and (6). The results are depicted in Figure S1, showing visually comparable results. Furthermore, there were only minor differences in T1 values and spatial variability (less than 1.5% for all methods). Due to the additional computational complexity associated with the calculation of the g-factor maps that yields minor changes, this approach was not preferred over the original denoising formulations. We also note that the g-factor approximation may further benefit from different rank choices, however this was not investigated in detail as it is beyond the scope of this study.

Fig. S1:

A representative cardiac phase is shown across different methods for original formulation and g-factor approach for approximating the reconstructed noise covariance matrices. Similar visual and quantitative improvement were observed in both approaches across the methods.

B. Appendix II

For the data acquisition model in Equation (1), an end-to-end inverse problem can be setup for reconstruction from k-space to image space. The objective function for the end-to-end inverse problem in the PARAFAC case can be written as

| (14) |

and in the Tucker case as

| (15) |

where Et,c: is as defined in Section II-A and n-rank of an N-dimensional tensor is the tuple of the rank of the matrix unfoldings along each mode, Ri =rank(Xi). This problem was solved by means of proximal gradient descent method in an iterative manner

where the proximal operator was implemented using the PARAFAC or Tucker ALS methods described in Section II. This iterative procedure was repeated until a convergence criterion was met. Figure S2 shows GRAPPA reconstruction, and PARAFAC global-3D and local-3D used in our work which are marked as PARAFAC LRTA, as well as the direct end-to-end inverse problem for PARAFAC global-3D and local-3D methods that are labeled as End-to-End Inversion. Our results indicate that both the LRTA approach used in our study and the end-to-end inverse problem solution yield similar improvement, while outperforming GRAPPA. The average precision for GRAPPA was 245±18 ms in this subject. The average T1 times were 1347±19 ms and 1349±26 ms, and precision values were 176±21 ms and 121±10 ms for PARAFAC global-3D and local-3D LRTA used in our work. In the end-to-end inversion setting, these values were 1342±17 ms and 1338±31 ms, and 187±19 ms and 124±10 ms for average T1 times and precision for PARAFAC Global-3D and local-3D, respectively. We note that end-to-end inversion may further benefit from different rank choices, however this was not investigated in detail due to the computational complexity of these methods.

Fig. S2:

Representative cardiac phases from one of the subjects used in this study for the PARAFAC LRTA formulation used in this study, as well as an end-to-end k-space-to-image inversion. Two approaches yield similar results both visually and quantitatively.

Contributor Information

Burhaneddin Yaman, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 55455..

Sebastian Weingärtner, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 55455..

Nikolaos Kargas, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 55455..

Nicholas D. Sidiropoulos, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, 22904..

Mehmet Akçakaya, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 55455..

References

- [1].He J, Liu Q, Christodoulou AG, Ma C, Lam F, and Liang ZP, “Accelerated High-Dimensional MR Imaging With Sparse Sampling Using Low-Rank Tensors,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 2119–2129, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Finn JP, Nael K, Deshpande V, Ratib O, and Laub G, “Cardiac MR imaging: state of the technology,” Radiology, vol. 241, no. 2, pp. 338–354, Nov 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, Liu K, Sunshine JL, Duerk JL, and Griswold MA, “Magnetic resonance fingerprinting,” Nature, vol. 495, no. 7440, pp. 187–192, Mar 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Descoteaux M, Deriche R, Le Bihan D, Mangin JF, and Poupon C, “Multiple q-shell diffusion propagator imaging,” Med Image Anal, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 603–621, Aug 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Christodoulou AG, Shaw JL, Nguyen C, Yang Q, Xie Y, Wang N, and Li D, “Magnetic resonance multitasking for motion-resolved quantitative cardiovascular imaging,” Nat Biomed Eng, vol. 2, pp. 215–226, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Feng L, Axel L, Chandarana H, Block KT, Sodickson DK, and Otazo R, “XD-GRASP: Golden-angle radial MRI with reconstruction of extra motion-state dimensions using compressed sensing,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 775–788, February 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weingartner S, Shenoy C, Rieger B, Schad LR, Schulz-Menger J, and Akcakaya M, “Temporally resolved parametric assessment of Z-magnetization recovery (TOPAZ): Dynamic myocardial T1 mapping using a cine steady-state look-locker approach,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 2087–2100, April 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Feng L, Coppo S, Piccini D, et al. , “5D whole-heart sparse MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 826–838, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Piccini D, Feng L, Bonanno G, et al. , “Four-dimensional respiratory motion-resolved whole heart coronary MR angiography,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 77, no. 4, pp. 1473–1484, 04 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Coppo S, Piccini D, Bonanno G, et al. , “Free-running 4D whole-heart self-navigated golden angle MRI: Initial results,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 74, pp. 1306–1316, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shaw JL, Yang Q, Zhou Z, Deng Z, Nguyen C, Li D, and Christodoulou AG, “Free-breathing, non-ECG, continuous myocardial T1 mapping with cardiovascular magnetic resonance multitasking,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 81, no. 4, pp. 2450–2463, April 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, and Boesiger P, “SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 952–962, November 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, and Haase A, “Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA),” Magn Reson Med, vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 1202–1210, June 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lustig M, Donoho D, and Pauly JM, “Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 1182–1195, December 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Akcakaya M, Nam S, Hu P, Moghari MH, Ngo LH, Tarokh V, Manning WJ, and Nezafat R, “Compressed sensing with wavelet domain dependencies for coronary MRI: a retrospective study,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1090–1099, May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Block KT, Uecker M, and Frahm J, “Undersampled radial MRI with multiple coils. Iterative image reconstruction using a total variation constraint,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1086–1098, June 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Haldar JP, Hernando D, and Liang ZP, “Compressed-sensing MRI with random encoding,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 893–903, April 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jung H, Sung K, Nayak KS, Kim EY, and Ye JC, “k-t FOCUSS: a general compressed sensing framework for high resolution dynamic MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 103–116, January 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Knoll F, Bredies K, Pock T, and Stollberger R, “Second order total generalized variation (TGV) for MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 480–491, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Akcakaya M, Basha TA, Goddu B, Goepfert LA, Kissinger K, Tarokh V, Manning WJ, and Nezafat R, “Low-dimensional-structure self-learning and thresholding: regularization beyond compressed sensing for MRI reconstruction,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 756–767, September 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lingala SG, Hu Y, DiBella E, and Jacob M, “Accelerated dynamic MRI exploiting sparsity and low-rank structure: k-t SLR,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1042–1054, May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Otazo R, Candes E, and Sodickson DK, “Low-rank plus sparse matrix decomposition for accelerated dynamic MRI with separation of background and dynamic components,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 1125–1136, March 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dong W, Shi G, Li X, Ma Y, and Huang F, “Compressive sensing via nonlocal low-rank regularization,” IEEE Trans Image Process, vol. 23, pp. 3618–3632, August 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhao B, Haldar JP, Christodoulou AG, and Liang ZP, “Image reconstruction from highly undersampled (k, t)-space data with joint partial separability and sparsity constraints,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 1809–1820, September 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Haldar JP, “Low-rank modeling of local k-space neighborhoods (LORAKS) for constrained MRI,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 668–681, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liang Z-P, “Spatiotemporal imagingwith partially separable functions,” in Proc. ISBI. IEEE, 2007, pp. 988–991. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liang Z-P, Jiang H, Hess CP, and Lauterbur PC, “Dynamic imaging by model estimation,” International journal of imaging systems and technology, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 551–557, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang T, Pauly JM, and Levesque IR, “Accelerating parameter mapping with a locally low rank constraint,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 655–661, February 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Trzasko JD and Manduca A, “Clear: Calibration-free parallel imaging using locally low-rank encouraging reconstruction,” in Proc. ISMRM, 2012, vol. 517. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Trzasko J, Manduca A, and Borisch E, “Local versus global low-rank promotion in dynamic mri series reconstruction,” in Proc. ISMRM, 2011, p. 4371. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Veraart J, Novikov DS, Christiaens D, Ades-Aron B, Sijbers J, and Fieremans E, “Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory,” Neuroimage, vol. 142, pp. 394–406, November 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Manjon JV, Coupe P, Concha L, Buades A, Collins DL, and Robles M, “Diffusion weighted image denoising using overcomplete local PCA,” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. e73021, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Moeller S, Weingartner S, and Akcakaya M, “Multi-scale locally low-rank noise reduction for high-resolution dynamic quantitative cardiac MRI,” Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, vol. 2017, pp. 1473–1476, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Trzasko J and Manduca A, “A unified tensor regression framework for calibrationless dynamic, multi-channel mri reconstruction,” in Proc. ISMRM, 2013, p. 603. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cichocki A, Mandic D, De Lathauwer L, Zhou G, Zhao Q, Caiafa C, and Phan HA, “Tensor decompositions for signal processing applications: From two-way to multiway component analysis,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 145–163, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ma C, Clifford B, Liu Y, Gu Y, Lam F, Yu X, and Liang ZP, “High-resolution dynamic 31 P-MRSI using a low-rank tensor model,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 419–428, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kargas N, Weingärtner S, Sidiropoulos ND, and Akçakaya M, “Low-rank tensor regularization for improved dynamic quantitative magnetic resonance imaging,” in SPARS, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mardani M, Ying L, and Giannakis G, “Accelerating dynamic mri via tensor subspace learning,” in Proc. ISMRM, 2015, p. 3808. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yu Y, Jin J, Liu F, and Crozier S, “Multidimensional compressed sensing MRI using tensor decomposition-based sparsifying transform,” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. e98441, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schelbert EB and Messroghli DR, “State of the Art: Clinical Applications of Cardiac T1 Mapping,” Radiology, vol. 278, no. 3, pp. 658–676, March 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S, Higgins DM, Sivananthan MU, and Ridgway JP, “Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 141–146, July 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM, Dall’Armellina E, Cochlin LE, Greiser A, Neubauer S, and Robson MD, “Shortened Modified Look-Locker Inversion recovery (ShMOLLI) for clinical myocardial T1-mapping at 1.5 and 3 T within a 9 heartbeat breathhold,” J Cardiovasc Magn Reson, vol. 12, pp. 69, November 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chow K, Flewitt JA, Green JD, Pagano JJ, Friedrich MG, and Thompson RB, “Saturation recovery single-shot acquisition (SASHA) for myocardial T(1) mapping,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 2082–2095, June 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Weingartner S, Akcakaya M, Basha T, Kissinger K, Goddu B, Berg S, Manning W, and Nezafat R, “Combined saturation/inversion recovery sequences for improved evaluation of scar and diffuse fibrosis in patients with arrhythmia or heart rate variability,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 1024–1034, March 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kale SC, Chen XJ, and Henkelman RM, “Trading off SNR and resolution in MR images,” NMR Biomed, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 488–494, June 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sotiropoulos SN, Moeller S, Jbabdi S, et al. , “Effects of image reconstruction on fiber orientation mapping from multichannel diffusion MRI: reducing the noise floor using SENSE,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 1682–1689, December 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Robson PM, Grant AK, Madhuranthakam AJ, Lattanzi R, Sodickson DK, and McKenzie CA, “Comprehensive quantification of signal-to-noise ratio and g-factor for image-based and k-space-based parallel imaging reconstructions,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 895–907, October 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Akcakaya M, Moeller S, Weingartner S, and Ugurbil K, “Scan-specific robust artificial-neural-networks for k-space interpolation (RAKI) reconstruction: Database-free deep learning for fast imaging,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 439–453, 01 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sidiropoulos ND, De Lathauwer L, Fu X, Huang K, Papalexakis EE, and Faloutsos C, “Tensor decomposition for signal processing and machine learning,” IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, vol. 65, no. 13, pp. 3551–3582, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kolda TG and Bader BW, “Tensor decompositions and applications,” SIAM review, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 455–500, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Weingartner S, Messner NM, Budjan J, Lossnitzer D, Mattler U, Papavassiliu T, Zollner FG, and Schad LR, “Myocardial T1-mapping at 3T using saturation-recovery: reference values, precision and comparison with MOLLI,” J Cardiovasc Magn Reson, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 84, November 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yaman B, Weingärtner S, Kargas N, Sidiropoulos ND, and Akcakaya M, “Locally low-rank tensor regularization for high-resolution quantitative dynamic mri,” in Proc. CAMSAP. IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhang X, Wen G, and Dai W, “A tensor decomposition-based anomaly detection algorithm for hyperspectral image,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 54, no. 10, pp. 5801–5820, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Deichmann R and Haase A, “Quantification of t1 values by snapshot-flash nmr imaging,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance, vol. 96, no. 3, pp. 608–612, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Koo TK and Li MY, “A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research,” J Chiropr Med, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 155–163, June 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bro R, “Parafac. tutorial and applications,” Chemometrics and intelligent laboratory systems, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 149–171, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vasilescu MAO and Terzopoulos D, “Multilinear analysis of image ensembles: Tensorfaces,” in European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2002, pp. 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Roujol S, Weingartner S, Foppa M, et al. , “Accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of four T1 mapping sequences: a head-to-head comparison of MOLLI, ShMOLLI, SASHA, and SAPPHIRE,” Radiology, vol. 272, no. 3, pp. 683–689, September 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gandy S, Recht B, and Yamada I, “Tensor completion and low-n-rank tensor recovery via convex optimization,” Inverse Problems, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 025010, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Liu J, Musialski P, Wonka P, and Ye J, “Tensor completion for estimating missing values in visual data,” IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 208–220, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]