Abstract

Background

Papillary thyroid carcinoma occasionally presents with concomitant hyperparathyroidism; however, the clinical significance has not been well established. This study aimed to evaluate the long-term cancer prognosis following a multimodality therapy.

Methods

We conducted a case-control study using prospectively maintained data from a medical center thyroid cancer database between 1980 and 2013. The study cohort comprised patients with concomitant papillary thyroid carcinoma and hyperparathyroidism. Patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma only were matched using the propensity score method. Therapeutic outcomes, including the non-remission rate of papillary thyroid carcinoma and patient mortality, were compared.

Results

We identified 27 study participants from 2537 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma, with 10 patients having primary hyperparathyroidism and 17 having renal hyperparathyroidism. Eighty-five percent of the cohort was found to have tumor–node–metastasis stage I disease. During a mean follow-up of 7.7 years, we identified 3 disease non-remission and 4 mortality events. The non-remission risk did not increase (hazard ratio [HR], 1.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43–6.40; p = 0.47); however, the overall mortality risk significantly increased (HR, 4.43; 95% CI, 1.11–17.75; p = 0.04). All mortality events were not thyroid cancer related, including two identified cardiovascular diseases.

Conclusions

Patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma who present with concomitant hyperparathyroidism are usually diagnosed at an early cancer stage with compatible therapeutic outcomes. However, hyperparathyroidism-related comorbidity may decrease long-term survival.

Keywords: Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Hyperparathyroidism, Therapeutic outcomes

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Papillary thyroid carcinoma is the most common endocrine malignancy, while hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcemia. Because the coexistence of these two diseases is not rare, careful preoperative evaluation helps with timely diagnosis and proper management. However, the long-term therapeutic outcome is unclear.

What this study adds to the field

Papillary thyroid carcinoma diagnosed with concomitant hyperparathyroidism usually presents in an indolent manner. Cancer recurrence could be observed after 5 years follow-up in few patients. Careful long-term surveillance should be suggested for high-risk patients. For patients with severe hyperparathyroidism at diagnosis, caregivers should consider cardiovascular risks.

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy, with an increasing incidence over recent decades [1]. Increased medical surveillance and access to healthcare services have led to the early detection of small suspicious thyroid lesions, which are most often confirmed as papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) or papillary thyroid microcarcinoma [2], [3]. Clinical practice management of patients with incidental PTC has become increasingly important. Hyperparathyroidism (HPT) is a relatively common endocrine disorder and is characterized with hypercalcemia. This metabolic abnormality potentiates the risks for osteoporosis, urolithiasis, and cardiovascular disease [4]. Parathyroidectomy is recommended for patients who are symptomatic, who have subclinical end-organ involved disease, or who have medical refractory disease [5], [6]. Additionally, the thyroid and parathyroid glands are anatomically closely located and show an association in disease development. Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated the increased risks for malignancy, including thyroid cancer, in both populations of primary HPT and renal HPT [7], [8]. Case series with coexisting thyroid cancer and parathyroid disorders have been described in several studies [9], [10], [11], [12]. However, the long-term prognosis for patients with concomitant PTC and HPT has not been specifically investigated. We conducted a study to evaluate therapeutic outcomes following a general multimodality therapy and to provide useful information concerning this particular patient population.

Material and methods

Patient enrollment and management

We enrolled study participants from 4062 consecutive patients who underwent thyroid cancer treatment, including 3267 patients with PTC, at the Chang Gung Medical Center in Linkou, Taiwan between 1980 and 2013. Patients who were lost to follow-up prior to 2014 and who had no pathological diagnoses recorded at our institute were excluded. Further grouping was conducted according to the presence of HPT. Diagnosis was based on an elevated serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) level with hypercalcemia and was confirmed with the surgical resection of an adenoma or hyperplastic glands. Patients with concomitant PTC and HPT comprised the PTC-with-HPT group. Patients with a history of non-concomitant HPT were excluded from further analysis. The remaining patients without HPT comprised the control group.

At our center, most patients with PTC having a tumor size of >1 cm underwent total thyroidectomy. Central or lateral dissection was performed for clinically enlarged lymph nodes or an extrathyroid extension. All tumors were staged after initial surgery based on the Union for International Cancer Control Tumor–Node–Metastasis (TNM) criteria (7th edition) [13]. The pathological classification of tumor tissues was performed according to the World Health Organization criteria [14]. Patients with an intermediate or high risk for recurrence were recommended for thyroid 131I remnant ablation for 4–6 weeks after initial thyroidectomy [15]. The 131I ablation dose was 1.1–3.7 GBq (30–100 mCi) for most patients. One week following 131I administration, a whole-body scan (WBS) was performed using a dual-head gamma camera (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA). Levothyroxine treatment was initiated to suppress thyroid-stimulating hormone levels without inducing clinical thyrotoxicosis. A neck ultrasonography was typically planned between 6 and 12 months following initial thyroidectomy to exclude the possibility of local recurrence. Higher 131I therapeutic doses of 3.7–7.4 GBq (100–200 mCi) may be administered to patients with locoregional or distant metastases. Patients who received doses exceeding 1.1 GBq (30 mCi) were isolated upon hospital admission according to the radiation regulations in Taiwan. During follow-up, the unstimulated or stimulated serum thyroglobulin (Tg) levels were measured using an immunoradiometric assay (CIS Bio International, Gif-sur-Yvette, France).

Outcomes definition and data collection

The therapeutic outcomes of patients with PTC were disease non-remission and mortality. We defined non-remission as an incomplete structural response to treatment. Non-remission events were categorized into residual disease and recurrent disease [16]. Residual disease was defined as initial 131I uptake extending beyond the thyroid bed, unless the result was proven to be false positive. Recurrent disease was defined as the presence of PTC 12 months following initial thyroidectomy. Diagnostic or therapeutic 131I scanning or other imaging techniques (that may or may not have been cytologically proven) indicated the non-remission status. A recurrent tumor was not included if it had been postoperatively diagnosed using a diagnostic or therapeutic 131I scan or if it was non-resectable. Mortality events were categorized into thyroid and non-thyroid cancer-related events. A composite outcome consisted of disease non-remission and mortality.

The thyroid cancer database of Chang Gung Medical Center in Linkou was established in 1995 and has been updated every 1 or 2 years [17]. Clinical data, including patient's age, sex, comorbidity, primary tumor size, surgical method, histopathological finding, and TNM staging; 4–6-week postoperative serum Tg level, therapeutic 131I scan, and 131I accumulated dose, and the clinical status for the analysis of locoregional or distant metastasis via noninvasive radiological and nuclear medical studies, treatment outcome, cause of death, and survival status were obtained for analysis. Data of concomitant HPT were collected by retrospective chart reviews. We acquired clinical data, including patient's presenting history, surgical indication, surgical method, preoperative serum intact-PTH level, and pathological findings.

Statistical analysis

To minimize the bias in the estimated effect (group difference) in this study, the PTC-with-HPT group was matched with the control group with a 1:5 ratio in terms of patient or tumor characteristics (age, sex, tumor size, surgical method with total or less than total thyroidectomy [subtotal thyroidectomy, lobectomy], presence of multifocality, presence of aggressive histology types [tall cell, insular and columnar cell], primary T [tumor] stage, presence of locoregional lymph node involvement, extrathyroid invasion, and distal metastasis) and follow-up period using the propensity score method (PSM). The PSM matching algorithm was based on the nearest-neighbor method and used the caliper radius (set as 0.2 sigma) that signifies a tolerance level for the maximum distance in the propensity score. The matching procedure was performed using R version 3.13 via PSM extension bundle in IBM SPSS software (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL USA).

Clinical characteristics between the two study groups (the PTC-with-HPT and control groups) were compared using the chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Time to the first occurrence of the predefined outcome (i.e., non-remission or death) after the date of diagnosis between the study groups was compared using Cox proportional hazard models with adjustment of the propensity score. The survival rate for the predefined period (i.e., until the date of recurrence or the last follow-up) for each study group was estimated and depicted using the Kaplan–Meier method along with the log-rank test. All data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS software version 23. This study was approved by the Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board.

Results

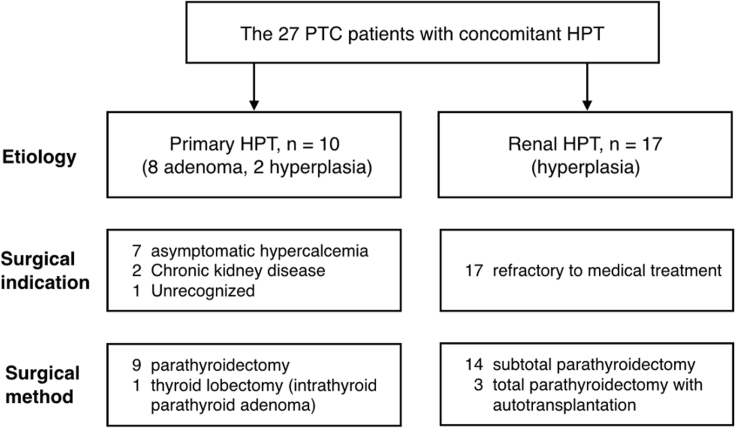

Among 2537 patients with PTC who underwent thyroidectomy and who received regular follow-up at our institute, 27 patients were diagnosed with concomitant HPT [Fig. 1]. We further identified 10 patients with primary HPT and 17 with renal HPT according to their presenting history [Fig. 2]. All participants of the PTC-with-HPT group underwent simultaneous thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy.

Fig. 1.

Enrollment of patients with PTC presenting with and without concomitant HPT.

Fig. 2.

Classification of parathyroid diseases in patients with concomitant PTC and HPT.

Characteristics of patients with concomitant PTC and HPT

Baseline characteristics of patients with PTC and primary and renal HPT were compared [Table 1]. All patients with renal HPT were initially under management for parathyroid diseases as part of chronic kidney disease care, and thyroid lesions were identified during examination. These patients had significantly elevated serum PTH levels before parathyroidectomy. In contrast, sequencing for disease detection was less homogeneous among patients with primary HPT. A relatively lower preoperative PTH level was also measured. All other characteristics showed no difference between the two subgroups. For the PTC-with-HPT group, preoperative diagnosis of thyroid neoplasm using fine needle aspiration cytology was made in only 26% of participants. Most malignant tumors were diagnosed using intraoperative frozen sections or incidentally through final pathology. Detection of abnormal lymph nodes during parathyroid exploration was the first indication of thyroid cancer in three patients. One patient underwent thyroidectomy for a single follicular neoplasm according to preoperative cytology. However, the final diagnosis was an intrathyroid parathyroid adenoma accompanied with one other incidental papillary microcarcinoma. Concomitant or incident PTC was usually found unexpectedly with a diverse presentation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the PTC patients with concomitant HPT.

| Characteristic, number (%) | Primary HPT (n = 10) | Renal HPT (n = 17) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 7 (70.0) | 11 (64.7) | 1.00 |

| Age at diagnosis (year)b | 57.3 [50.3; 67.5] | 48.7 [38.5; 60.0] | 0.13 |

| Intact-PTH level (pg/mL)b | 801.2 [170.8; 1292.8] | 1609.2 [862.5; 2248.5] | 0.03a |

| Initial approach for thyroid/parathyroid | 3/7 | 0/17 | 0.04a |

| Pre-operative cytology of thyroid neoplasm | 4 (40.0) | 3 (17.6) | 0.37 |

| Tumor size of PTC (cm)b | 1.4 [0.4; 2.4] | 1.4 [0.5; 1.7] | 0.71 |

| Classic PTC/Follicular variant PTC | 7/3 | 13/4 | 1.00 |

| Multifocality | 2 (20.0) | 4 (23.5) | 1.00 |

| Limited to thyroid gland | 9 (90.0) | 12 (70.6) | 0.36 |

| Locoregional lymph node involvement | 1 (10.0) | 4 (23.5) | 0.62 |

| Extrathyroid invasion | 1 (10.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1.00 |

| Follow-up period (year)b | 8.4 [3.7; 12.1] | 7.6 [3.1; 13.2] | 0.64 |

Statistical significance.

Presented as mean [quartiles].

Compared with patients in the control group, those in the PTC-with-HPT group were diagnosed at an older age with a smaller-sized tumor on an average [Table 2]. They underwent less advanced surgical intervention and received a lower mean accumulative dose of radioiodine ablation therapy. All other clinical characteristics showed no difference between the two groups. Furthermore, the difference in the distribution of the patient or tumor characteristics between the two groups was no longer apparent after PSM matching. Non-matching parameters, such as the one-month postoperative serum Tg level, postoperative 131I cumulative dose, and secondary primary cancer, were also balanced between the two groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the PTC patients before and after PSM matching.

| Characteristic, number (%) | Before PSM Matching |

After PSM Matching |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control (n = 2508) | PTC-with-HPT (n = 27) | p-value | control (n = 103) | PTC-with-HPT (n = 26) | p-value | |

| Sex, female | 1977 (78.8) | 18 (66.7) | 0.15 | 75 (72.8) | 18 (69.2) | 0.81 |

| Age at diagnosis (year)b | 43.6 [33; 53] | 51.9 [39; 61] | 0.002a | 47.6 [39; 58] | 50.9 [39; 60] | 0.25 |

| Tumor size (cm)b | 2.3 [1.2; 3.0] | 1.4 [0.5; 1.7] | <0.001a | 1.4 [0.5; 1.9] | 1.3 [0.5; 1.6] | 0.97 |

| Multifocality | 621 (24.8) | 6 (22.2) | 1.00 | 20 (19.4) | 6 (23.1) | 0.79 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Classic PTC | 2099 (83.7) | 20 (74.1) | 0.19 | 91 (88.3) | 19 (73.1) | 0.06 |

| Follicular variant PTC | 375 (15.0) | 7 (25.9) | 12 (11.7) | 7 (26.9) | ||

| Others | 34 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| Stage I | 1747 (69.7) | 23 (85.2) | 0.09 | 90 (87.4) | 23 (88.5) | 1.00 |

| Stage II | 233 (9.3) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (3.9) | 0 | ||

| Stage III | 194 (7.7) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (3.9) | 1 (3.8) | ||

| Stage IV | 334 (13.3) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (4.9) | 2 (7.7) | ||

| Operative method | ||||||

| Total thyroidectomy | 2173 (86.6) | 19 (70.4) | 0.02a | 72 (69.9) | 18 (69.2) | 1.00 |

| Less than total | 335 (13.4) | 8 (27.6) | 31 (30.1) | 8 (30.8) | ||

| 1M-Post-op Tg (ng/mL)b | 158.8 [0; 18.3] | 35.2 [0; 18.3] | 0.64 | 30.7 [0; 22.6] | 36.7 [1.5; 19.8] | 0.67 |

| Post-op131I dose (mCi)b | 130.8 [30; 150] | 99.3 [0; 100] | 0.04a | 94.6 [0; 105] | 103.1 [0; 108] | 0.92 |

| Secondary primary cancer | 178 (7.1) | 2 (7.4) | 0.72 | 6 (5.8) | 2 (7.7) | 0.66 |

| Follow-up period (year)b | 9.5 [3.8; 14.3] | 7.9 [3.9; 11.9] | 0.32 | 8.9 [3.5; 12.3] | 7.7 [3.5; 11.8] | 0.50 |

Abbreviations: 1M-Post-op Tg: one-month postoperative serum thyroglobulin level; Post-op 131I dose: postoperative 131I cumulative dose.

Statistical significance.

Presented as mean [quartiles].

Therapeutic outcomes analysis

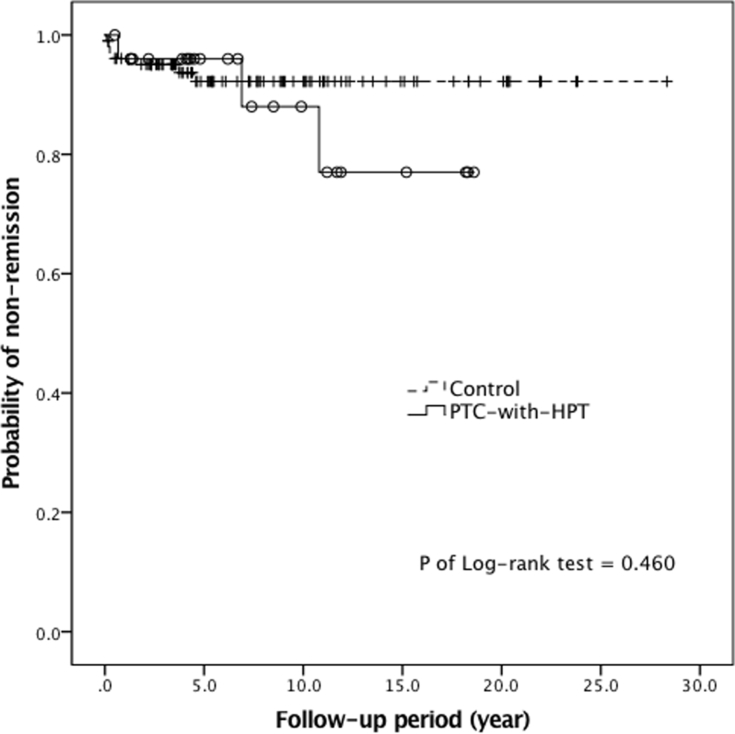

Patients in the PTC-with-HPT group had non-remission events, including one residual and two recurrent diseases during follow-up [Table 3]. Although the non-remission rate was numerically higher in the PTC-with-HPT group than in the control group, the progression-free survival in the two groups was not different [Fig. 3]. With respect to patient mortality, no thyroid cancer-related deaths occurred in the PTC-with-HPT group, although four non-thyroid cancer-related deaths occurred. The PTC-with-HPT group had a poorer overall survival compared with the control group [Fig. 4]. In summary, more than one-fourth of patients in the PTC-with-HPT group had either disease non-remission or mortality. Their event rate of composite outcome was significantly higher than the rate of the control group.

Table 3.

Therapeutic outcomes of the PTC-with-HPT group and control group.

| Outcome | Number of events (%) |

PTC-with-HPT vs. control |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTC-with-HPT | Control | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Residual disease | 1 (3.8) | 4 (3.9) | 0.96 (0.11–8.60) | 0.97 |

| Recurrent disease | 2 (7.7) | 3 (2.9) | 2.59 (0.43–15.50) | 0.30 |

| Disease non-remission | 3 (11.5) | 7 (6.8) | 1.66 (0.43–6.40) | 0.47 |

| Thyroid cancer related mortality | 0 | 1 (1.0) | NA | NA |

| Non-thyroid cancer related mortality | 4 (15.4) | 3 (2.9) | 5.93 (1.32–26.52) | 0.02a |

| Overall mortality | 4 (15.4) | 4 (3.9) | 4.43 (1.11–17.75) | 0.04a |

| Composite outcome | 7 (26.9) | 10 (9.7) | 2.79 (1.06–7.33) | 0.04a |

Abbreviations: HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; NA: not applicable.

Statistical significance.

Fig. 3.

Progression-free survivals of the PTC-with-HPT group (solid line, circle) and the control group (dash line, cross).

Fig. 4.

Overall survivals of the PTC-with-HPT group (solid line, circle) and the control group (dash line, cross).

Clinical characteristics of patients with disease non-remission or mortality were analyzed [Table 4]. The only case with residual disease involved a 53-year-old women who showed increased multiple focal uptake in the neck region after initial 131I administration with 2 mCi. Pulmonary micro-metastasis was diagnosed using WBS with 100 mCi ablation therapy. Follow-up serum Tg levels were undetectable in terms of thyroxine supplement status. A 31-year-old man and a 54-year-old man showed biochemically incomplete responses to sequential radioiodine treatment. They were finally confirmed as having locoregional recurrence more than five years after initial thyroidectomies. Concerning mortality, the identifiable causes of death involved two cardiovascular events. The first patient, a 44-year-old women with IgA nephropathy, received renal replacement therapy for 16 years at the time of PTC diagnosis. She showed cancer remission after initial therapy but died of a non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage with uncal herniation at the age of 53. The second patient, a 63-year-old women, had been undergoing hemodialysis therapy for >10 years prior to undergoing total thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy. She had remained in cancer remission status; however, at the age of 68, she was admitted to hospital with acute limb ischemia. She died a few days after an emergent below-knee amputation.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the PTC-with-HPT group: non-remission and mortality.

| Characteristic | Non-remission (n = 3) | Mortality (n = 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, sex | 53, F | 31, M | 54, M | 44, F | 65, F | 61, F | 63, F |

| Pathology of PTC | C | C | C | C | C | C | FV |

| Multifocality | no | yes | yes | no | no | no | no |

| Tumor size (cm), stage | 0.2, T1A | 1.0, T1A | 4.0, T4A | 2.4, T4A | 0.4, T1A | 1.5, T1B | 1.4, T1B |

| Lymph nodes status | N0 | N1A | N1A | N0 | N0 | N0 | N0 |

| TNM stage | SI | SI | SVIa | SI | SI | SI | SI |

| Total thyroidectomy | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes |

| 1M-Post-op Tg (ng/mL) | 13.8 | 512 | 63.6 | 2.95 | 64.2 | – | 13.7 |

| Post-op131I dose (mCi) | 100.0 | 420.0 | 490.0 | 29.8 | – | – | 30.0 |

| Time-to-event (year) | 0.7 | 10.8 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| Location or death cause | neck, lung | neck | neck | stroke | unknown | unknown | ALI |

| Second primary cancer | no | RCC, HCC | no | no | TCC | no | no |

| Etiology of HPT | primary | renal | primary | renal | renal | renal | renal |

F, female; M, male; C, classic; FV, follicular variant; 1M-Post-op Tg, one-month postoperative serum thyroglobulin level; Post-op 131I dose, postoperative 131I cumulative dose; ALI, acute limb ischemia; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TCC, transitional cell carcinoma.

Discussion

In our study, concomitant PTC and HPT occasionally occurred. The prevalence rate of concomitant HPT was 1.1% for patients with PTC. Most of the patients were diagnosed at an early cancer stage; however, disease non-remission following a multimodality therapy was observed in some patients. We showed that non-cancer-related mortality resulted in inferior survival of patients with concomitant PTC and HPT. A cardiovascular event is considered to be one of the major causes of death.

Diagnosis of patients with concomitant PTC and HPT can be categorized into parathyroid and thyroid approaches according to the sequence of disease detection. Researchers have reported that between 24.7% and 73.3% of patients who underwent parathyroidectomy also had thyroid nodules [9], [10], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. Thyroid cancer was diagnosed in 1.8%–4.9% of patients of the whole population using the parathyroid approach. Both primary HPT and renal HPT study cohorts have shown similar prevalence rates [12], [23]. In contrast, studies using the thyroid approach have shown that between 2.0% and 5.0% of patients admitted for thyroidectomy underwent simultaneous parathyroidectomy for HPT [11], [24], [25]. In our cohort of confirmed patients with PTC, the parathyroid approach was more commonly observed. One possible reason could be that concomitant thyroid lesions were usually identified during parathyroid examination. In contrast, serum PTH and calcium levels were not routinely assessed prior to thyroid surgery. Subclinical HPT tended to be underestimated. Therefore, we recommend that thyroid ultrasonography with or without fine needle aspiration is likely to provide useful information concerning patients admitted for parathyroidectomy. This procedure is likely to assist in the detection of occult malignancy and avoid unexpected changes to surgical planning [9], [20], [22], [26]. Moreover, intraoperative evaluation is important because concomitant papillary thyroid microcarcinoma or lymph node metastasis may not be detected or confirmed prior to surgery [21]. For patients undergoing thyroidectomy, preoperative evaluation of serum calcium and PTH levels is not complicated. This noninvasive procedure prevents neglecting concomitant parathyroid disorders. However, the cost–benefit effects require further evaluation [12], [25]. For accurate diagnosis and management, clinical awareness following careful evaluation should be emphasized.

The mechanism underlying the relationship between PTC and HPT remains unclear [23], [27]. Some researchers have proposed that the two diseases have a genetic association or share common environmental factors [12], [19]. High PTH levels, low 1,25-hydroxy vitamin D levels, and hypercalcemia are assumed to induce goiter or cancer cell growth [28]. These predisposing factors are commonly observed in both primary and renal HPT. A small number of cross-sectional studies or epidemiological investigations have shown supporting but limited evidence [29], [30]. Our longitudinal study provides further information in terms of cancer prognosis. Most patients with PTC and HPT can be classified as a low-risk group, with an incomplete structural response rate to treatment being <7% [16]. The current risk stratification system functioned predictively well in our cohort. All our low-risk patients had no recurrent disease. Two other patients with risk factors such as initial gross extrathyroid tumor extension and inappropriately high postoperative Tg levels showed late-onset recurrence after 8.9 years on an average. However, there was no statistical difference in non-remission rates between the PTC-with-HPT group (11.5%) and the control group (6.8%). The recurrence group difference may have been underestimated because the increased non-cancer-related mortality shortened the follow-up period in the concomitant HPT group. Hence, we recommend careful monitoring of the cancer status as well as any underlying comorbidity for the population with concomitant PTC and HPT.

HPT may be associated with cardiovascular diseases [31]. Although most patients with primary HPT presented without overt symptoms and regained normocalcemia after parathyroidectomy, increased cardiovascular mortality has been observed in populations with severe disease even after treatment [32], [33]. In contrast, patients with chronic kidney disease usually start to develop secondary HPT because their disease progresses to advanced stage, as evidenced by estimated glomerular filtration rates of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Vascular calcification and increased cardiovascular risks are well established by the time parathyroidectomy is performed for a refractory disease [34]. In previous reports of concomitant thyroid cancer and parathyroid disease, populations with renal HPT have been less often reported [12], [23], [29]. However, approximately two-thirds of patients belonged to the renal HPT in our cohort. This unique patient distribution could be explained through the high prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan [35]. An extremely elevated preoperative PTH level indicated the high disease severity of our patient group. All mortality occurred in patients with renal HPT who had chronic metabolic abnormality. We inferred that cardiovascular complications were more serious than an incidental thyroid cancer finding for patients with renal HPT, especially in an era where optimal management for refractory HPT has not yet been achieved.

Our study had limitations because it was a retrospective study with a case-control design and limited number of patient. Further large-scale prospective studies for patients with primary and renal HPT should be conducted. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study designed to evaluate the prognosis of patients and concomitant PTC and HPT. We described their long-term therapeutic outcomes, highlighted the treatment challenges in clinical practice, and provided useful information for improving patient care.

In conclusion, PTC diagnosed with concomitant HPT usually presents in an indolent manner as do other early PTCs. It is important for treatment of concomitant diseases to be individualized. Careful long-term cancer surveillance for >5 years is suggested for high-risk patients. Evaluation of cardiovascular risk may be necessary for patients with severe HPT, especially owing to renal causes. Prompt management of refractory HPT is recommended.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital [grant number: CMRPG3E1901] and by the Ministry of Science and Technology [grant number: 106-2314-B-182-042] to Jen-Der Lin.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2019.05.010.

Contributor Information

Chih-Yiu Tsai, Email: b8802016@cgmh.org.tw.

Jen-Der Lin, Email: einjd@adm.cgmh.org.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.La Vecchia C., Malvezzi M., Bosetti C., Garavello W., Bertuccio P., Levi F. Thyroid cancer mortality and incidence: a global overview. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2187–2195. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaccarella S., Dal Maso L., Laversanne M., Bray F., Plummer M., Franceschi S. The impact of diagnostic changes on the rise in thyroid cancer incidence: a population-based study in selected high-resource countries. Thyroid. 2015;25:1127–1136. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahl M., Sosa J.A., Nelson R.C., Esclamado R.M., Choudhury K.R., Hoang J.K. Trends in incidentally identified thyroid cancers over a decade: a retrospective analysis of 2,090 surgical patients. World J Surg. 2014;38:1312–1317. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griebeler M.L., Kearns A.E., Ryu E., Hathcock M.A., Melton L.J., 3rd, Wermers R.A. Secular trends in the incidence of primary hyperparathyroidism over five decades (1965–2010) Bone. 2015;73:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilezikian J.P., Brandi M.L., Eastell R., Silverberg S.J., Udelsman R., Marcocci C. Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: summary statement from the Fourth International Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3561–3569. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellorin-Font E., Ambrosoni P., Carlini R.G., Carvalho A.B., Correa-Rotter R., Cueto-Manzano A. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of mineral and bone disorders in chronic kidney disease (CKD-MBD) in adults. Nefrologia. 2013:1–28. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2013.Feb.11945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer M., Adami H.O., Krusemo U.B., Ljunghall S. Increased risk of malignant diseases after surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. A nationwide cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:1031–1040. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickard A.L., Gridley G., Mellemkjae L., Johansen C., Kofoed-Enevoldsen A., Cantor K.P. Hyperparathyroidism and subsequent cancer risk in Denmark. Cancer. 2002;95:1611–1617. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita S.Y., Somervell H., Umbricht C.B., Dackiw A.P., Zeiger M.A. Evaluation for concomitant thyroid nodules and primary hyperparathyroidism in patients undergoing parathyroidectomy or thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2008;144:862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.029. discussion 6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sloan D.A., Davenport D.L., Eldridge R.J., Lee C.Y. Surgeon-driven thyroid interrogation of patients presenting with primary hyperparathyroidism. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray S.E., Sippel R.S., Chen H. Incidence of concomitant hyperparathyroidism in patients with thyroid disease requiring surgery. J Surg Res. 2012;178:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jovanovic M.D., Zivaljevic V.R., Diklic A.D., Rovcanin B.R., Zoric G.V., Paunovic I.R. Surgical treatment of concomitant thyroid and parathyroid disorders: analysis of 4882 cases. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2017;274:997–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4303-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edge S.B., American Joint Committee on Cancer . 7th ed. Springer; New York: 2010. AJCC cancer staging manual. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLellis R.A. IARC Press; Lyon: 2004. Pathology and genetics of tumours of endocrine organs. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin J.D., Hsueh C., Chao T.C. Early recurrence of papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma predicts a worse outcome. Thyroid. 2009;19:1053–1059. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haugen B.R., Alexander E.K., Bible K.C., Doherty G.M., Mandel S.J., Nikiforov Y.E. American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liou M.J., Tsang N.M., Hsueh C., Chao T.C., Lin J.D. Therapeutic outcome of second primary malignancies in patients with well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Int J Endocrinol. 2016;2016:9570171. doi: 10.1155/2016/9570171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips D.J., Kutler D.I., Kuhel W.I. Incidental thyroid nodules in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Head Neck. 2014;36:1763–1765. doi: 10.1002/hed.23533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehwald N., Cupisti K., Krausch M., Ahrazoglu M., Raffel A., Knoefel W.T. Coincidence of primary hyperparathyroidism and nonmedullary thyroid carcinoma. Horm Metab Res. 2013;45:660–663. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa T., Kammori M., Tsuji E., Kanauchi H., Kurabayashi R., Terada K. Preoperative evaluation of thyroid pathology in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Thyroid. 2007;17:59–62. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gul K., Ozdemir D., Korukluoglu B., Ersoy P.E., Aydin R., Ugras S.N. Preoperative and postoperative evaluation of thyroid disease in patients undergoing surgical treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:7–13. doi: 10.4158/EP09138.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arciero C.A., Shiue Z.S., Gates J.D., Peoples G.E., Dackiw A.P., Tufano R.P. Preoperative thyroid ultrasound is indicated in patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. J Cancer. 2012;3:1–6. doi: 10.7150/jca.3.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seehofer D., Rayes N., Klupp J., Nussler N.C., Ulrich F., Graef K.J. Prevalence of thyroid nodules and carcinomas in patients operated on for renal hyperparathyroidism: experience with 339 consecutive patients and review of the literature. World J Surg. 2005;29:1180–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lokey J.S., Palmer R.M., Macfie J.A. Unexpected findings during thyroid surgery in a regional community hospital: a 5-year experience of 738 consecutive cases. Am Surg. 2005;71:911–913. discussion 3-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Rio P., Arcuri M.F., Bezer L., Cataldo S., Robuschi G., Sianesi M. Association between primary hyperparathyroidism and thyroid disease. Role of preoperative PTH. Ann Ital Chir. 2009;80:435–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentrem D.J., Angelos P., Talamonti M.S., Nayar R. Is preoperative investigation of the thyroid justified in patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for hyperparathyroidism? Thyroid. 2002;12:1109–1112. doi: 10.1089/105072502321085207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause U.C., Friedrich J.H., Olbricht T., Metz K. Association of primary hyperparathyroidism and non-medullary thyroid cancer. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:685–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beebeejaun M., Chinnasamy E., Wilson P., Sharma A., Beharry N., Bano G. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: is there a link? Med Hypotheses. 2017;103:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miki H., Oshimo K., Inoue H., Kawano M., Morimoto T., Monden Y. Thyroid carcinoma in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Surg Oncol. 1992;49:168–171. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930490308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin S.Y., Lin W.M., Lin C.L., Yang T.Y., Sung F.C., Wang Y.H. The relationship between secondary hyperparathyroidism and thyroid cancer in end stage renal disease: a population based cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker M.D., Silverberg S.J. Cardiovascular aspects of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Endocrinol Investig. 2008;31:925–931. doi: 10.1007/BF03346443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer M., Adami H.O., Bergstrom R., Jakobsson S., Akerstrom G., Ljunghall S. Survival and renal function in untreated hypercalcaemia. Population-based cohort study with 14 years of follow-up. Lancet. 1987;1:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91906-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clifton-Bligh P.B., Nery M.L., Supramaniam R., Reeve T.S., Delbridge L., Stiel J.N. Mortality associated with primary hyperparathyroidism. Bone. 2015;74:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L., Wang K., Yu S., Lai L., Zhang X., Yuan J. Long-term mortality after parathyroidectomy among chronic kidney disease patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2016;38:1050–1058. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1184924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang S.J., Tsai J.C., Chen H.C. Epidemiology, impact and preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.