Summary

Background

In patients with hematological malignancies, febrile neutropenia (FEN) is the most frequent complication and the most important cause of mortality. Various risk factors have been identified for severe infection in neutropenic patients. However, to the best of our knowledge, it is not defined whether there is a change in the risk of febrile neutropenia according to seasons. The first aim of study was to determine the difference in frequency of febrile neutropenic episodes (FNEs) according to months and seasons. The second aim was to document isolated pathogens, as well as demographical and clinical characteristics of patients.

Methods

In the study, 194 FNEs of 105 patients who have been followed with hematological malignancies between June 2013 and May 2014 were evaluated retrospectively.

Results

Although the number of FNEs increased in autumn, there was no significant difference in frequency of FNEs between months (p = 0.564) and seasons (p = 0.345). There was no isolated pathogen in 54.6% of FNEs. In 45.4% of 194 FNEs, pathogens were isolated. Of all pathogens, 50.4% were gram negative bacteria, 29.2% were gram positive bacteria, 13.3% were viruses, 5.3% were fungi, and 1.8% were parasites.

Conclusıons

The frequency of FEN does not change according to months or seasons. Also, the relative proportions of different pathogens in the cause of FEN do not vary according to seasons.

Keywords: Neutropenia, Fever, Seasons, Months, Hematological

Introduction

Febrile neutropenia (FEN) is the most common complication requiring hospitalization and causing mortality in patients with hematological cancer. Also, febrile episodes prolong the duration of hospitalization in neutropenic patients [1].

Clinically documented infections occur in 20–30% of febrile episodes [2, 3]. Most of the infections documented in patients with FEN are caused by endogenous flora [4]. Among these, circulatory and respiratory system infections are the most common. While gram negative bacteria were the most frequently detected infectious agents up until the 1980s, gram positive bacteria became the most common factors in the following years, due to increased use of vascular catheters, prophylactic antibiotic applications, and toxic intestinal chemotherapy applications. However, in recent years, the rate of gram negative bacteria has increased again [5–9]. Commonly seen gram positive bacteria are S. aureus, coagulase negative Staphylococcus (CNS), and Streptococcus species; gram negative bacteria include E. coli, Klebsiella species, and P. aeruginosa [10]. Fungal agents, most commonly Candida and Aspergillus, can also be identified as causes of FEN.

Severe neutropenia, prolonged neutropenia, presence of mucositis, type of cancer (such as acute leukemia, high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome), uncontrolled or progressive cancer, induction therapy or application of intensive chemotherapy such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, presence of comorbid disorders requiring hospitalization, use of central venous catheter, use of monoclonal antibody, poor performance status, and advanced age are some of the risk factors defined for FEN development [11].

To the best of our knowledge, seasons or months have not been defined as risk factors for FEN in hematological cancer patients. The primary aim of the study was to investigate whether there is a relationship between the frequency of febrile neutropenic episodes (FNEs) and seasons in hematological cancer patients. The second aim of the study was to determine the type and frequency of pathogens detected in FNEs.

Materials and methods

In this study, 194 FNEs of 105 patients with hematological malignancies who had been followed at a multidisciplinary hospital (Akdeniz University School of Medicine Hospital) between June 2013 and May 2014 were evaluated. Patients with allogeneic stem cell transplants were not included in the study. The available medical files and biological results of all 105 patients were retrospectively reviewed.

According to the ASCO guidelines, fever was defined as a single oral temperature measurement of >38.3 °C (101 °F) or a temperature of >38.0 °C (100.4 °F) sustained over a one hour period. We defined neutropenia as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <500 cells/mm3 or an ANC that was expected to decrease to <500 cells/mm3 during the next 48 h [12].

Clinical and demographic data of the patients and the months and seasons of FNEs were noted. In addition, neutrophil count, C‑reactive protein (CRP) level, length of hospitalization, culture results of blood and other body specimens, isolated pathogens, detected foci of infection, and antibacterial, antiviral, or antifungal treatments were reviewed. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Akdeniz University School of Medicine Hospital and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization. In addition to descriptive statistical methods (mean, median, and standard deviation), the χ2 test was used to compare qualitative data, and the Student’s t‑test was used for quantitative two-group comparisons of the parameters with normal distribution. The results were evaluated with a confidence interval of 95% and a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

There were 69 (65.7%) male and 36 (34.3%) female patients. The median length of hospital stay was 26.5 days (3–82). Demographic characteristics of the cases are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients

| Sex a | |

| Female | 36 (34%) |

| Male | 69 (66%) |

| Age b | |

| All | 60 (21–89) |

| Female | 58 (21–88) |

| Male | 61 (22–89) |

| Malignancy a | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 20 (10.3%) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 80 (41.2%) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 5 (2.6%) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 2 (1%) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 4 (2.1%) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 49 (25.3%) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 21 (10.8%) |

| Multiple myeloma | 10 (5.2%) |

| Hairy cell leukemia | 2 (1%) |

| Plasma cell leukemia | 1 (0.5%) |

| ECOG performance status a | |

| 1 | 88 (45.4%) |

| 2 | 66 (34%) |

| 3 | 36 (18.5%) |

| 4 | 4 (2.1%) |

| Status of malignancy a | |

| Newly diagnosed | 65 (33.5%) |

| Remission | 53 (27.3%) |

| Relapsed-refractory | 72 (37.1%) |

| Stable disease or partial response | 4 (2.1%) |

an (%)

bMedian (min–max); ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

The FNEs occurring during a given period of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia were 90% of all FNEs, and the chemotherapy regimens included 18 different protocols. Ten percent of FNEs were not related to chemotherapy. The mean number of FNEs was 1.78 ± 0.91 in females, 1.86 ± 1.16 in males, and 1.83 ± 1.08 in all patients. There was no difference in the number of FNEs according to gender (p = 0.748). The median neutrophil count was 80 (0–990)/mm3 and the median CRP level was 6 mg/dl (0.2–32; normal range: 0–0.5). No pathogen was detected in 54.6% of FNEs. In 76 of the FNEs, only one microorganism was isolated, while in 12 FNEs, more than one microorganism was isolated. Isolated microorganisms are presented in Table 2. Of the isolated bacterial microorganisms, 63.3% were gram negative bacteria and 36.7% were gram positive bacteria. Among gram negative bacteria, the most commonly isolated bacterium was E. coli. The most frequently isolated bacterium among gram positive bacteria was CNS.

Table 2.

Microorganisms isolated in episodes of febrile neutropenia

| (n: 113) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 90 | 79.6 |

| Gram negative | 57 | 50.4 |

| Escherichia coli | 24 | 21.1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 9 | 8 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 7 | 6.2 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 | 4.4 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 4 | 3.5 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3 | 2.7 |

| Citrobacter koseri | 2 | 1.8 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 | 0.9 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | 0.9 |

| Pantoea | 1 | 0.9 |

| Gram positive | 33 | 29.2 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 16 | 14.2 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 14 | 12.3 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | 0.9 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 | 0.9 |

| Corynebacterium jeikeium | 1 | 0.9 |

| Virus | 15 | 13.3 |

| İnfluenza virus | 6 | 5.3 |

| Herpes virus | 4 | 3.5 |

| Human rhinovirus | 2 | 1.8 |

| Coronavirus | 1 | 0.9 |

| Rinosinsitial virus | 1 | 0.9 |

| Parainfluenza virus | 1 | 0.9 |

| Fungal | 6 | 5.3 |

| Candida albicans | 2 | 1.8 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 4 | 3.5 |

| Parasite | 2 | 1.8 |

| Amoeba | 2 | 1.8 |

In 64 (32.9%) FNEs, no clinical focus of infection was detected, while in 130 (67.1%) FNEs, a total of 175 possible clinical foci of infection were detected. Of these, a single focus was detected in 97 FNEs and multiple foci were detected in 33 FNEs. The clinical foci of infection in FNEs are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Infection foci in FEN episodes

| (n: 175) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Respiratory Path | 60 | 34.3 |

| Blood | 23 | 13.1 |

| Upper Respiratory Path | 19 | 10.9 |

| Gastrointestinal System | 17 | 9.7 |

| Catheter | 17 | 9.7 |

| Skin—Soft Tissue | 17 | 9.7 |

| Urinary | 11 | 6.3 |

| Paranasal Sinus | 8 | 4.6 |

| Dental | 3 | 1.7 |

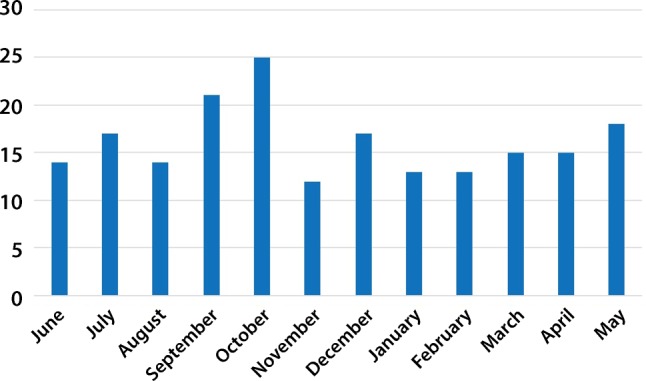

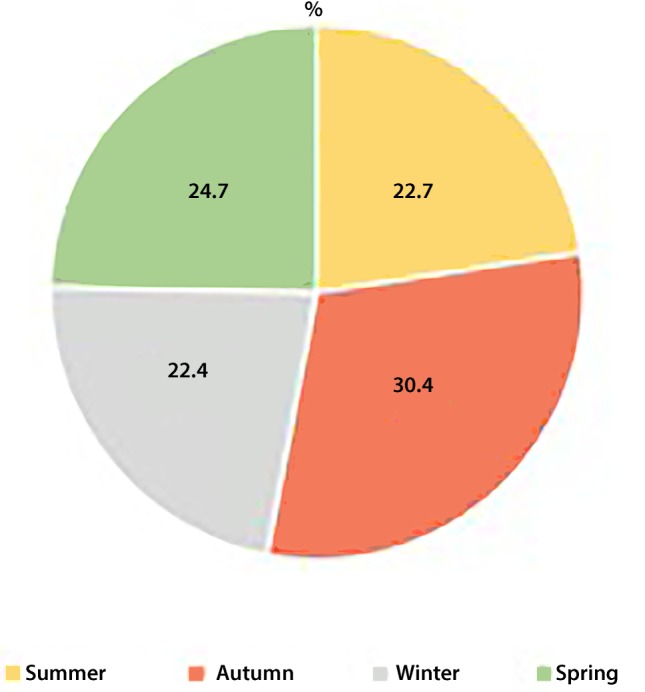

Although the number of FNEs increased in autumn, there was no significant difference in frequency of FNEs between months (p = 0.564) and seasons (p = 0.345) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Number of febrile neutropenia attacks by months

Fig. 2.

Rate of febrile neutropenia attacks by seasons

It was observed that 78 (40.2%) FNEs were treated with single antibacterial therapy and 116 (59.8%) FNEs were treated with combined antibacterial treatment. Antifungal treatment was added to antibacterial treatment in 76 (39.1%) FNEs, and antiviral treatment was applied in 15 (7.7%) FNEs. The management did not differ according to particular seasons.

Twenty-seven (13.9%) of the 194 FNEs resulted in death. The main causes of death were sepsis (74.1%), intracranial bleeding (14.8%), and acute respiratory distress (11.1%).

Discussion

Today, various cytotoxic antineoplastic therapies are widely used in hematological cancers. However, there is an increase in the frequency of infections due to myelosuppression and immunosuppression caused by the disease itself and current treatments. Studies show that life-threatening infection occurs in 48–60% of FEN patients [13]. Seasonal patterns of infection can be observed for some of the viruses that cause the common cold. In temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, the frequency of respiratory infections increases rapidly in autumn, remains fairly high throughout winter, and decreases again in spring. In tropical areas, most colds arise during the rainy season [14, 15]. Based on the presence of seasonal viral infection patterns, this study investigated whether there was a similar seasonal change in FNEs. It was found that there was no difference in frequency of FNEs according to months and seasons. The probable reason why there is no difference according to months and seasons is that the pathogens are largely caused by endogenous flora.

The second aim of the study was to determine the type and frequency of pathogens detected in FNEs in patients with hematologic cancer. The proportion of gram negative bacteria was significantly higher (approximately twice as much) than the ratio of gram positive bacteria. Among all pathogens, E. coli was the most common (21.2%). Also, these pathogens did not show any change according to seasons. Therefore, empirical antimicrobial therapy does not require a change according to the seasons. FEN is a medical emergency and empirical treatment should be started as soon as possible. The aim of empirical therapy is to cover the most likely and most virulent pathogens that may rapidly cause life-threatening infections. Therefore, clinicians need to be aware of the current microbiology surveillance data from their own institution, which can vary widely from center to center. This allows for better management of the process with selection of more appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy.

The limitation of the study was that the follow-up period of the participants was not sufficient. A study with a longer follow-up period is needed to more thoroughly investigate seasonal frequency in febrile neutropenia. A more wide view of the whole world practice is needed.

It would be nice to know the frequencies of admissions for febrile episodes per month and per season also for non-cancer patients in order to evaluate if the seasonal variations of infections which have been reported elsewhere can be also observed in our region. Although there is no reported study in our region, it can be said that viral infections are more common in autumn and winter months. If a more comprehensive study is to be carried out, the presence of a non-cancer control group will provide clearer information.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all treating physicians in our center for collaboration and data collection.

Conflict of interest

S.K. Özdemir, U. Iltar, O. Salim, O.K. Yücel, R. Erdem, Ö. Turhan, and L. Undar declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106(10):2258–2266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of Americaa. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):427–431. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pizzo PA. Management of fever in patients with cancer and treatment-induced neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(18):1323–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schimpff SC, Young VM, Greene WH, et al. Origin of infection in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Significance of hospital acquisition of potential pathogens. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77(5):707–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-5-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodey GP, Jadeja L, Elting L. Pseudomonas bacteremia. Retrospective analysis of 410 episodes. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(9):1621–1629. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360090089015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, et al. 2002 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(6):730–751. doi: 10.1086/339215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, et al. Current trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients with hematological malignancies and solid neoplasms in hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(9):1103–1110. doi: 10.1086/374339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland T, Fowler VG, Jr, Shelburne SA., 3rd Invasive gram-positive bacterial infection in cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(Suppl 5):S331–S334. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viscoli C, Castagnola E. Treatment of febrile neutropenia: what is new? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002;15(4):377–382. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sipsas NV, Bodey GP, Kontoyiannis DP. Perspectives for the management of febrile neutropenic patients with cancer in the 21st century. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1103–1113. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyman GH, Abella E, Pettengell R. Risk factors for febrile neutropenia among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;90(3):190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flowers CR, Seidenfeld J, Bow EJ, et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis and outpatient management of fever and neutropenia in adults treated for malignancy: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;20;31(6):794–810. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.8661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruciani M, Rampazzo R, Malena M, et al. Prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones for bacterial infections in neutropenic patients: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(4):795–805. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick GL. The common cold. Prim Care. 1996;23(4):657–675. doi: 10.1016/S0095-4543(05)70355-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heikkinen T, Järvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]