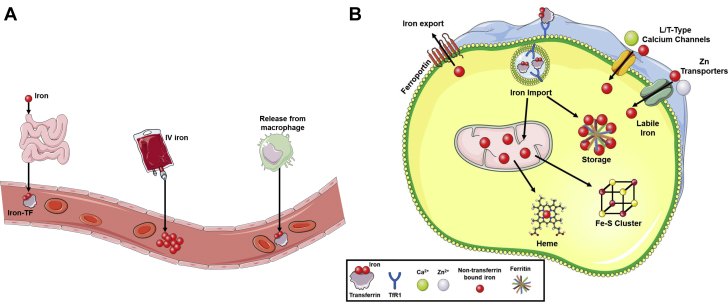

Figure 2.

Cellular Iron Regulation and Systemic Transport

(A) A graphic depicting different forms of iron transport through blood vessels. Under normal physiologic conditions, iron is absorbed from the small intestine or recycled through macrophages and released as Tf-bound iron. However, clinical use of intravenous (IV) iron in patients with iron deficiency introduces a large bolus of non–transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) into the vessel. Although the IV iron can be in colloids based on small spheroidal iron-carbohydrate particles, NTBI is redox active and can form reactive oxygen species, damaging endothelial cells. (B) A graphic depicting the import and fate of cellular iron. The uptake of transferrin (Tf)-bound iron is mediated through binding to transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) and subsequent internalization by endocytosis. The acidic environment of the lysosome liberates iron from the Tf-TfR1 complex, and iron is transported into the cytosol, whereas the Tf-TfR1 complex is recycled to the cell surface. Upon entry into the cytosol, the majority of iron is bound by the storage molecule ferritin, and a small amount remains as labile iron. Non–Tf-mediated iron uptake can also occur through L/T-type calcium channels and zinc transporters. Once in the cell, iron can be transported into the mitochondria for the synthesis of heme or Fe/S clusters. The only mechanism capable of removing iron from the cell is via export through ferroportin.