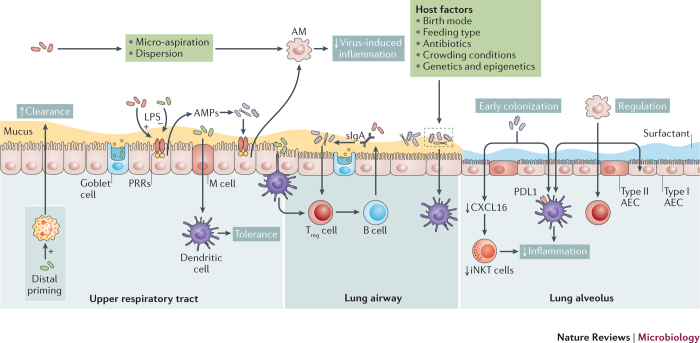

Figure 3. Host–microbiota interactions in the respiratory tract.

Host–microbiota interactions in the respiratory tract occur mostly at the mucosal surface. Resident microorganisms prime immune cells either locally or systemically; these include epithelial cells, neutrophils and dendritic cells, which all contribute to the clearance of pathogens. Moreover, microbial signalling is necessary for the recruitment and activation of regulatory cells, such as anti-inflammatory alveolar macrophages (AMs) and regulatory T cells (Treg cells). Locally, the host will respond to microbial colonization through the release of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA). Sensing of the microbiota involves microfold (M) cells that activate tolerogenic dendritic cells. In addition, alveolar dendritic cells can directly sample luminal microorganisms. Together, these pathways lead to the regulation of inflammation and the induction of tolerance, which, in turn, shape resident bacterial communities. It is also plausible that early bacterial colonization is key to long-term immune regulation, which is illustrated by the microbiota-induced decrease in hypermethylation of the CXC-motif chemokine ligand 16 (Cxcl16) gene, which prevents the accumulation of inducible natural killer T cells (iNKT cells), and by the programmed death ligand 1 (PDL1)-mediated induction of tolerogenic dendritic cells (Box 3). This tolerant milieu, in turn, contributes to the normal development and maintenance of resident bacterial communities, which are also influenced by host and environmental factors (Fig. 1). AEC, alveolar epithelial cell; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; PRR: pattern recognition receptor; URT, upper respiratory tract.