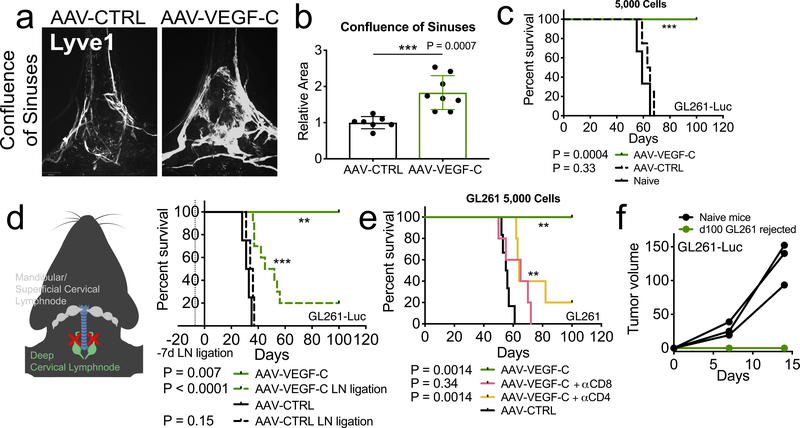

Figure 1. Increased meningeal lymphatic vasculature confers protection against intracranial glioblastoma challenge in a draining lymph node and T cell dependent manner and provides long-term protection.

a-b C57BL/6 mice received injection of AAV-CTRL or AAV-VEGF-C intra-cisternally (icm) through the cisterna magna. Six to eight weeks later, mice were euthanized and the dura was collected to image the lymphatic vasculature (LYVE1+) in the confluence of sinuses (AAV-CTRL, n = 7; AAV-VEGF-C, n = 8). c-e C57BL/6 mice injected with CTRL-AAV or AAV-VEGF-C icm two months prior were implanted with 5,000 (e) (Naïve = 3, AAV-CTRL, n = 4; AAV-VEGF-C, n = 8) GL261-Luc cells in the striatum and monitored for survival. d Six to eight weeks after AAV icm injection, the dcLNs of mice were ligated using a cauterizer. Seven days later, mice were challenged with 50,000 GL261-Luc cells in the striatum and monitored for survival (AAV-CTRL, n = 4; AAV-CTRL LN ligation, n = 4; AAV-VEGF-C, n = 4; AAV-VEGF-C LN ligation, n = 10). f Mice injected with AAV-CTRL or AAV-VEGF-C that survived over 100 days after 5,000 GL261-Luc challenge were re-challenged with 500,000 GL261-Luc in the flank. IVIS imaging of mice ten days after flank re-challenge, and measurement of tumors at day 7 and 15 (n = 3). Data are pooled from two independent experiments (b-f). Data are mean ± S.D. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P <0.001; ****P<0.0001 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, two-sided Log-rank Mantel-Cox test)