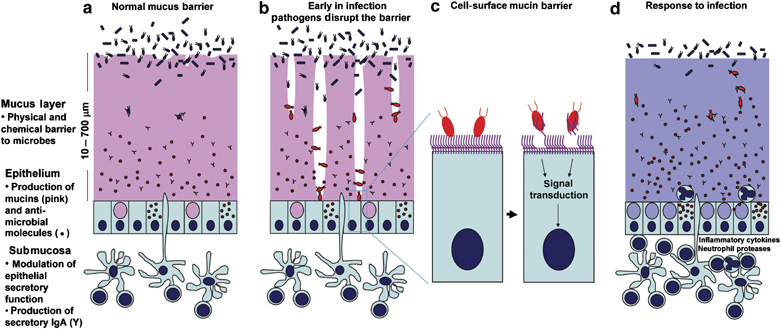

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. (a) The normal mucosa is covered with a continuously replenished thick mucus layer retaining host-defensive molecules. Commensal and environmental microbes may live in the outer mucus layer but the layer ensures that contact of microbes with epithelial cells is rare. (b) Early in infection, many pathogens actively disrupt the mucus layer and thereby gain access to the epithelial cell surface. In addition, this alters the environment for commensal and environmental microbes and opportunistic pathogenesis may occur. (c) Pathogens that break the secreted mucus barrier reach the apical membrane surface, which is decorated with a dense network of large cell-surface mucins. Pathogens bind the cell-surface mucins via lectin interactions and the mucin extracellular domains are shed as releasable decoy molecules. Consequent to contact with microbes and shedding of the extracellular domain, signal transduction by the cytoplasmic domains of the cell-surface mucins modulates cellular response to the presence of microbes. (d) In response to infection, there are alterations in mucins that are driven directly by epithelial cells and in response to signals from underlying innate and adaptive immunity. These alterations include goblet cell hyperplasia and increased mucin secretion and altered mucin glycosylation (depicted by the color change) affecting microbial adhesion and the ability of microbes to degrade mucus. These changes in mucins work in concert with other arms of immunity to clear the infection.