Abstract

Although human speech recognition is often experienced as relatively effortless, a number of common challenges can render the task more difficult. Such challenges may originate in talkers (e.g., unfamiliar accents, varying speech styles), the environment (e.g. noise), or in listeners themselves (e.g., hearing loss, aging, different native language backgrounds). Each of these challenges can reduce the intelligibility of spoken language, but even when intelligibility remains high, they can place greater processing demands on listeners. Noisy conditions, for example, can lead to poorer recall for speech, even when it has been correctly understood. Speech intelligibility measures, memory tasks, and subjective reports of listener difficulty all provide critical information about the effects of such challenges on speech recognition. Eye tracking and pupillometry complement these methods by providing objective physiological measures of online cognitive processing during listening. Eye tracking records the moment-to-moment direction of listeners’ visual attention, which is closely time-locked to unfolding speech signals, and pupillometry measures the moment-to-moment size of listeners’ pupils, which dilate in response to increased cognitive load. In this paper, we review the uses of these two methods for studying challenges to speech recognition.

Keywords: Speech recognition, Eye tracking, Pupillometry, Listening effort

1. Introduction

Recognizing speech requires listeners to map acoustic input onto long-term linguistic representations. This process is highly complex, even under optimal conditions, because the acoustics of a single word or speech sound vary significantly from talker to talker and from utterance to utterance. On top of that, many everyday conditions complicate the situation: we talk to each other in noisy spaces, we come from different language and dialect backgrounds, and some of us cope with the added challenges of speech, hearing, or language impairments. All of these situations can reduce the intelligibility of spoken language.

Even when intelligibility is maintained, however, such challenges can place greater processing demands on listeners (Peelle, 12018). Difficult listening conditions can, for example, differentially deplete the cognitive resources required for encoding information in memory, with noise or hearing loss leading to poorer recall for spoken material, even when it has been correctly identified (Rabbitt, 1968, 1991; Piquado et al., 2012; Suprenant, 1999, 2007; Cousins et al., 2014; Pichora-Fuller et al., 1995; McCoy et al., 2005; Heinrich and Schneider, 2011; Ng et al., 2015; Mishra et al., 2014). Similarly, challenging conditions can lead to poorer performance on secondary tasks performed while listening to speech (Picou and Ricketts, 2014; Picou et al., 2013; Sarampalis et al., 2009; Fraser et al., 2010; Gosselin and Gagne, 2011; Hicks and Tharpe, 2002). Assuming that cognitive capacity is limited and the two tasks (e.g., speech recognition and visual flash recognition) must compete for cognitive resources, such costs indicate that difficult listening conditions deplete the cognitive resources that would otherwise be available for performing other tasks.

Measures of memory and dual-task performance quantify the consequences of listening challenges after effortful listening has taken place. Methods that allow researchers to measure listeners’ responses as the speech unfolds, therefore, represent a critical complement to such measures. In this paper, we review two of these online techniques—eye tracking and pupillometry—both of which allow us to look at speech perception in real time. By recording the moment-to-moment direction of listeners’ eye gaze, eye tracking provides fine-grained temporal information about the locus of visual attention, allowing researchers to assess the time course of target word recognition and the alternative interpretations of the speech signal listeners might entertain during recognition. Pupillometry, by contrast, measures a physiological correlate of cognitive load,1,2 pupil dilation, allowing for the quantification of cognitive effort during speech recognition without depending on a behavioral response to the speech.

2. Eye tracking

Cooper (1974) first showed that people tend to “spontaneously direct their line of sight to those elements which are most closely related to the meaning of the language currently heard” (p. 84). Despite the promise of eye tracking for studying the perception of spoken language, the metho—now known as the visual world paradigm (VWP, Allopenna et al., 1998)—did not take hold in psycholinguistics until approximately twenty years later with the publication of Tanenhaus et al.’s (1995) “Integration of Visual and Linguistic Information in Spoken Language Comprehension.”

Since then, eye tracking has had broad application for research on all levels of language comprehension. It has been used extensively, for example, to study sentence processing, including studies of syntactic ambiguity resolution (e.g., Tanenhaus et al., 1995; Trueswell et al., 1999; Dahan et al., 2002; Trueswell and Gleitman, 2004; Snedeker and Trueswell, 2004; Chambers et al., 2004), adjective interpretation (Huang and Snedeker, 2013; Leffel et al., 2016), the interpretation of pronouns, demonstratives, and reflexives (e.g., Arnold, 2001; Arnold et al., 2000; Kaiser et al., 2009; Kaiser and Trueswell, 2008), and children’s interpretations of referential expressions in adult input (Arunachalam, 2016). Eye tracking has also been informative for studying the interpretation of prosody (e.g., Kurumada et al., 2014; Dahan et al., 2002; Weber et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2008; Ito and Speer, 2008), the time-course of pragmatic inferences (Breheny et al., 2013; Englehardt et al., 2006; Sedivy et al., 1999; Grodner and Sedivy, 2011; Huang and Snedeker, 2009a, b; Panizza et al., 2009; Grodner et al., 2010; Heller et al., 2008; Wolter et al., 2011; Schwarz, 2014), and the processing of disfluencies in the speech stream (Arnold et al., 2003, 2004, 2007; Bailey and Ferreira, 2007). Since the goal of this paper is to review research on speech recognition in challenging conditions, this section will focus on eye tracking studies of word and sentence recognition. For a broader review of the use of the visual world paradigm for studying language processing, see Huettig et al. (2011).

The general consensus among current models of spoken word recognition is that multiple lexical candidates are activated when a word is heard. The activation of those candidates depends on the degree of match between the input and the listener’s stored lexical representations; and activated candidates compete for recognition (see Weber and Scharenborg, 2012 for a review). Early evidence for the parallel activation of multiple candidates came from priming studies, which showed, for example, that an onset consistent with two words (e.g., “cap” for both captain and captive) facilitated recognition of semantically related words to both of the possible words (ship and guard) (Marslen-Wilson, 1987; Zwitserlood, 1989). Continuous mapping models of spoken word recognition (e.g., TRACE by McClelland and Elman, 1986 and Shortlist by Norris, 1994) predicted, further, that rhyming words should also be at least weakly activated, but evidence from offline studies was inconclusive. By allowing for the assessment of competition during the presentation of the auditory stimulus, eye tracking provided an opportunity to investigate whether the activated set of words (i.e., the competitor set) was onset-based or more global.

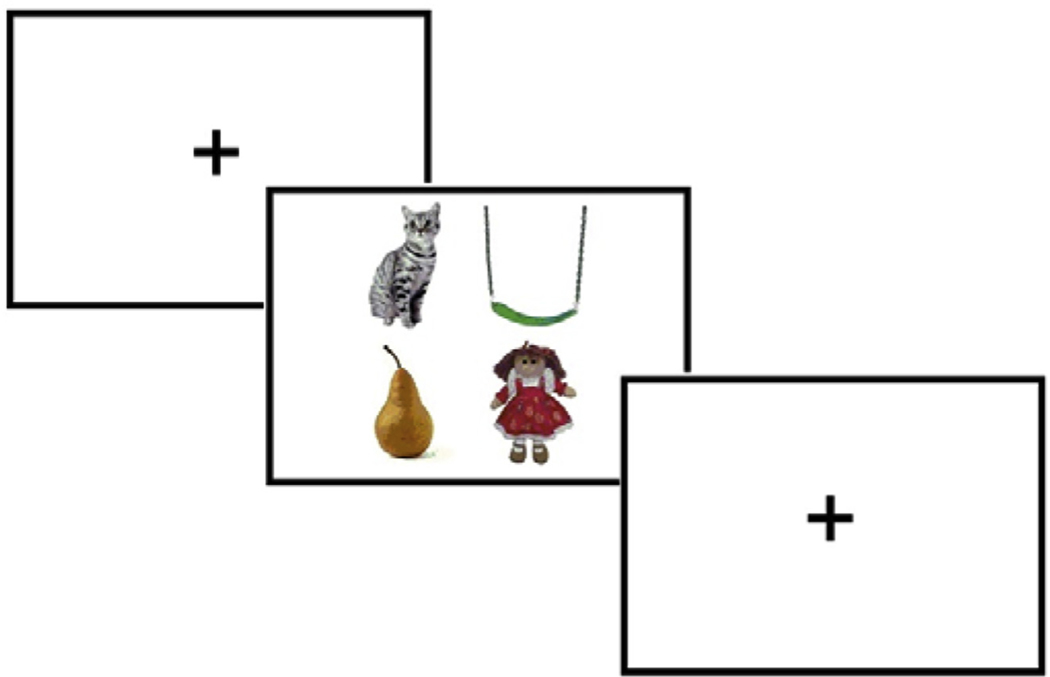

In Allopenna et al.’s now-classic 1998 paper, listeners were presented with visual arrays (see sample in Fig. 1) containing four images: one corresponded to a target word (e.g. “beaker”), one to a cohort competitor of the target (e.g., “beetle”), one to a rhyme competitor (e.g., “speaker”), and one to a phonologically and semantically unrelated item (e.g., a “carriage”). Participants’ eye movements to the four objects were monitored as they heard spoken instructions such as “Pick up the beaker; now put it below the diamond.” Like Tanenhaus et al. (1995), this study showed that eye movements occurring early during the presentation of the target were as likely to result in fixations to the cohort competitor (“beetle”) as they were to the target word (“beaker”). Critically, however, it also showed a slightly later increase in fixations to the rhyme competitor (“speaker”), which matched the latter part of the target signal. This study thus provided evidence in favor of continuous mapping models of word recognition, which predicted that the set of activated alternatives during word recognition should include words that differed in onset. It also confirmed that information at the beginning of a word is indeed generally more important for constraining lexical selection than information at the end of a word (see also McQueen and Viebahn (2007), which showed similar results using printed words in the visual array).

Fig. 1.

Sample array for the visual world paradigm.

Subsequent eye tracking studies have continued to refine our understanding of the dynamics of lexical activation and competition under optimal listening conditions. Such work has shown, for example, that lexical activation is sensitive to fine phonetic detail (e.g., McMurray et al., 2002; Salverda et al., 2003) and that acoustic cues affect word recognition as soon as they become available (McMurray et al., 2008). At the lexical level, VWP studies have also demonstrated that high-frequency words are recognized more quickly than low-frequency words (Magnuson et al., 2007; Dahan et al., 2001) and that high-frequency competitors exert greater competition on target words than low-frequency competitors (Dahan et al., 2001; Dahan and Gaskell, 2007). Furthermore, the frequency effect appears to persist beyond the time point in the speech signal where the target and competitor can be distinguished, indicating that the effects of lexical competition last longer than the temporal unfolding of the spoken word (Dahan and Gaskell, 2007). The VWP has also shown that cohort density (i.e., the number of words that begin similarly to the target) and neighborhood density (i.e., the number of words that differ from the target by a single phoneme) affect word recognition, even when there are no competitors in the visual array (Magnuson et al., 2007): words with common onsets, for example, are slower to be recognized, presumably because of increased lexical competition.

In recent years, eye tracking has increasingly been employed to examine how challenges inherent to everyday speech communication affect lexical activation and competition. In the sections that follow, we review the eye tracking literature on challenges arising from signal degradation (i.e., noise), listener factors (i.e., hearing loss, cochlear implants, aging, and language experience), and talker factors (i.e., variability, reduction, and accent).

2.1. Signal degradation

One of the unavoidable features of many of the spaces in which people communicate is the presence of noise. Whether it’s a crowded restaurant, a busy classroom, or the ambient sounds of heating and cooling systems, we rarely talk to each other in spaces as quiet as speech laboratories. Much of what is known about the effects of such noise on speech recognition is based on intelligibility measures (i.e., offline reports of what listeners can understand in noisy conditions), but eye tracking has allowed us to begin investigating how noise affects the online processes of word recognition (e.g., Ben-David et al., 2011; McQueen and Huettig, 2012; Brouwer and Bradlow, 2015; Helfer and Staub, 2014).

Generally speaking, these studies show that word recognition is slower and characterized by greater lexical competition when speech signals are degraded. Ben-David et al. (2011), for example, showed that noise delayed the time point at which listeners launched saccades away from a fixation cross and increased competition from both onset and cohort competitors. Noise can also shift the relative strength of different competitors: McQueen and Huettig (2012) used visual displays that included pictures of competitors but critically no picture corresponding to the auditory target word (Huettig and Altmann, 2005) – an approach that is particularly sensitive for assessing the relative strength of different competitors during word recognition. When target words (presented in the clear) were surrounded by sentences that were interrupted by noise, the dynamics of lexical competition shifted: listeners looked less at onset competitors and more at rhyme competitors, suggesting that noisy environments led listeners to treat the signal (and/or themselves as listeners) as less reliable, even when the word itself was presented without distortion.

Furthermore, eye tracking shows that different types of noise have different effects on the dynamics of word recognition: Brouwer and Bradlow (2015) found that rhyme competition was increased and persisted longer in broadband noise than in quiet. With a competing talker in the background, they also found that the content of the noise influenced lexical competition: onset competition was reduced when rhyme competitors were activated by words in the noise. In a comparison of steady-state noise and interfering speech, Helfer and Staub (2014) found not only that competing speech was more detrimental for accuracy on the task (i.e., choosing one of two words from a visual display), but that accurate responses were slower in competing speech conditions. Further, listeners were more likely to look at the competitor, looked at it longer, and took longer to fixate the target word when the background noise was speech. Taken together, these studies indicate that the linguistic content of background noise alters both the time course of lexical activation and the dynamics of lexical competition.

2.2. Listener-related challenges: hearing impairment, aging, and language experience

2.2.1. Hearing impairment

Although hearing impairment is another common source of auditory signal degradation during speech recognition, only a small number of studies to date have used eye tracking to investigate its effects. Wendt et al. (2015) presented sentences to listeners with and without sensorineural hearing loss in quiet, stationary speech-shaped noise, and amplitude-modulated speech-shaped noise, finding that listeners with hearing impairment (and particularly those who had not previously used hearing aids) were slower to process the sentences, even when intelligibility was high and matched with intelligibility for normal-hearing (NH) listeners.

McMurray and colleagues have begun to address lexical activation and competition in listeners with impaired hearing by comparing cochlear implant (CI) users to NH listeners (McMurray et al., 2016, 2017). In their studies, participants were presented with tokens from six b/p continua and 6 s/S continua constructed from words (i.e., ranging from “beach” to “peach” or “sip” to “ship”). Participants were asked to select the picture corresponding to the word they heard, and eye movements were monitored to investigate how strongly they considered the other member of the word pair. All listeners showed gradient responses corresponding to the acoustic variability in the signals, but across the continua, CI users looked at competitors more than listeners with normal hearing. The authors interpret this result as evidence that CI users “amplify” competitor activation to preserve their flexibility as listeners in the face of potential perceptual errors (similar to the interpretation that noise increases rhyme activation because listeners are uncertain about onset identity). McMurray et al. (2017) also compared pre-lingually deaf CI users to NH listeners. CI users showed a significant delay in fixating to objects, less competition from onset competitors, and more competition from rhyme competitors compared to NH listeners. The same pattern was observed for NH listeners when they were presented with degraded speech (i.e., noise-vocoded using four channels), suggesting—like the noise studies above-—that NH listeners also adjust the dynamics of lexical access in order to delay access until sufficient information has accumulated.

2.2.2. Aging

Although hearing loss commonly accompanies old age, the trouble older listeners experience with speech recognition is often not accounted for by hearing thresholds alone (e.g., Plomp and Mimpen, 1979; Smoorenburg, 1992). Thus, understanding the interplay of sensory and cognitive mechanisms in older adulthood is a major focus of research on speech perception in this population. Eye tracking holds significant promise as a tool for studying how sensory and cognitive declines associated with aging may shape the online processing of speech, because the saccadic motor system is not significantly slowed by aging (Pratt et al., 2006).

As such, VWP studies have been used to identify some subtle differences in the dynamics of lexical activation and competition as listeners age. Ben-David et al. (2011), for example, found that, although spoken word processes were largely similar across younger and older adults, older adults were slightly more affected by rhyme competition. Younger listeners, they argue, may resolve rhyme competition extremely quickly since the difference between the target and competitor is at the very start of the word. Onset competition requires more of the word to unfold before the target and competitor can be distinguished, perhaps giving older adults the time they need to “catch up” to younger adults when distinguishing targets from onset competitors.

In addition to this increased rhyme competition, Revill and Spieler (2012) also suggests that older adults are more reliant on lexical frequency than younger adults during word recognition: older adults were more likely to fixate high-frequency targets and high-frequency phonological competitors than were younger adults. Furthermore, degrading the auditory quality of the signals for younger adults did not produce a similar pattern.

Finally, eye tracking has shown that competing speech slows word recognition for older adults more than it does for younger adults (Helfer and Staub, 2014). Although older subjects in that study behaved very much like younger subjects in quiet and speech-shaped noise, their accuracy in competing speech was lower, their RTs for correct trials were slower, and their eye movement data showed that fixations to the target were slowed to a greater degree.

2.2.3. Language experience

To date, only a small number of studies have used the VWP to investigate how listener language experience affects online speech recognition. In one such study, Weber and Cutler (2004) found that non-native English listeners (native speakers of Dutch) showed evidence of greater lexical competition overall, and their eye movements indicated that distractors with Dutch names that were similar to the English target (e.g., deksel, ‘lid’ given the English target ‘desk’) received longer fixations than other distractors. Dutch listeners also looked longer at competitors containing vowels that are often confused by native Dutch speakers with the vowels in the target word (e.g., pencil for panda) compared to competitors with different vowels. The authors conclude not only that lexical competition is greater for non-native listeners overall, but also that first language phoneme categories “capture” second-language input.

Hanulíková and Weber (2012) similarly used the VWP to investigate the effect of listeners’ native language (L1) on second-language (L2) word recognition. They tracked eye movements to printed words while native Dutch and German listeners heard English words (produced by German- and Dutch-accented talkers) in which /th/ was replaced with /t/ (the typical Dutch replacement), /s/ (the typical German replacement), or /f/ (the most perceptually similar option). Dutch listeners tended to look to the /t/ variants while Germans tended to look to the /s/ variants and English listeners did not show a preference. Thus, non-native listeners processed the variant with which they had the most experience more quickly than one that was more similar to the target.

2.3. Talker-related challenges: variability, reduction, and accent

Even when there is no particular challenge to contend with, speech signals are highly variable. An individual talker, for example, will produce the vowel /u/ differently from utterance to utterance, depending on the phonetic context, prosodic context (e.g., “I want a boot.” vs. “I want the BOOT; not the shoe.”), speaking style (e.g., talking to a hearing-impaired friend vs. a friend with normal hearing), or their emotional state. Much of this variation goes un-noticed by listeners, but when a talker deviates significantly from a listener’s native-language norms, it can become challenging.

To begin to investigate the effect of phoneme gradience during word recognition, McMurray et al. (2002) used word pairs that differed only in the voicing of the initial consonant (e.g., “beach” and “peach”). When listeners were presented with tokens whose voice onset time (VOT) values were closer to the phoneme boundary (i.e., “peach” with a shortened VOT), more looks were elicited to the voicing competitor (i.e., “beach”), even though the word was still identified as the intended target (“peach”). That is, cross-category competition was greater when tokens were closer to the phoneme boundary. In a later study, Clayards et al. (2008) showed that listeners’ sensitivity to this kind of fine-grained acoustic detail is optimal with regard to the distribution of acoustic cues in their environments.

Speaking style represents a common source of such variation in spoken language. In casual speech, words are often highly reduced, so that individual sounds and even entire syllables are unpronounced (e.g., “computer” may be produced as “puter”). Using eye tracking, Brouwer et al. (2012) showed that competition during word recognition depended on whether the talker was producing reduced speech or fully-articulated speech. When words in the sentence surrounding a target were reduced, listeners looked equally to competitors that were similar to the canonical form and those that were similar to the reduced form. When the surrounding speech was fully articulated, listeners showed a clear preference for the canonical competitor. In a follow up study, Brouwer et al. (2013) showed, further, that supportive discourse context was more important for the recognition of reduced forms than canonical forms.

The common deviations from canonical forms that characterize casual speech, however, do not typically deviate from native-speaker norms. In fact, failing to produce native-like reduction can make a non-native talker sound more accented. Talkers with unfamiliar accents and dialects, however, may produce speech that strays enough from native norms that listeners experience noticeable difficulty in understanding it (Van Engen and Peelle, 2014). Studies assessing the intelligibility of foreign-accented speech show that listeners can adapt quite quickly to improve their recognition of accented speech (e.g., Clarke and Garrett, 2004; Bradlow and Bent, 2008), and eye tracking has shown that accent adaptation involves dynamic adjustments of lexical representations in accordance with the current talker or context: Dahan et al. (2008) exposed listeners to words produced by a speaker of an American dialect in which /ae/ is raised before /g/ but not before /k/. This exposure facilitated listeners’ recognition of words ending in /k/ because the change in vowel before /g/ reduced the competition from a word ending in /g/.

In addition to segmental adaptation, Reinisch and Weber (2012) showed that listeners display short-term, speaker-specific adaptation to suprasegmental patterns in foreign-accented speech. This study exposed native Dutch listeners to non-canonical lexical stress patterns from an unfamiliar accent (Hungarian). Using eye tracking for the test phase, they found that listeners exposed to the Hungarian-accented Dutch were better able to distinguish target-competitor pairs that had segmental overlap (but different stress patterns) than listeners who had only been exposed to canonical stress patterns.

Most recently, the VWP has been used to investigate the extent to which degree of foreign accent affects the time course of spoken word recognition, with word recognition taking longer for more strongly accented speech than for weakly accented speech (Porretta et al., 2016). That study also showed that the time-course of word recognition was shorter for listeners who had experience with the accent in question (Mandarin-accented English): it took a much stronger accent to slow down experienced listeners, whereas people with little experience were slowed by milder accents. Whether lexical factors (e.g. frequency, neighborhood density) or the dynamics of onset and rhyme competition are affected by accent remains to be seen: Porretta et al. (2016) only analyzed looks to the targets. If, as in speech-in-noise studies, listeners are generally less confident about having correctly identified onsets in accented speech, we might expect increased competition from rhyme competitors during the recognition of accented speech.

2.4. Eye tracking summary

By recording the locus of visual attention during auditory speech recognition, eye tracking has proven to be an invaluable tool for studying communication challenges. In general, these studies show that listening challenges slow the process of word recognition: noisy conditions, hearing impairment, and accented speech all lead to delays in fixations to target words. The amount of slowing, of course, depends on the details of these challenges: speech noise slows recognition more than non-speech noise (especially for older adults), and the effect of accent depends on the accent strength and the listener’s experience with the accent in question.

In addition to general slowing, eye tracking also shows that listening challenges change the dynamics of lexical competition. When signals are degraded, competitor activation is increased overall for NH listeners, listeners with hearing impairment or cochlear implants, and non-native listeners. Older adults appear to be differentially affected by lexical frequency (both in terms of target and competitor activation) and by competition from rhyme competitors (i.e., words that differ from targets at onset, but share later phonetic material), while non-native listeners’ patterns of competition are influenced by their particular language experience. In general, looks to competitors in these studies suggest that listeners treat themselves and/or the speech signal as less reliable in challenging conditions, considering competitor words to a greater extent rather than relying on initial perceptions.

The direction of listeners’ visual attention is not the only information we can get from the eyes during speech perception. In the next section, we turn to pupillometry and its contribution to the literature on speech perception in challenging situations.

3. Pupillometry

The pupil is commonly known to constrict and dilate in response to lighting (Reeves, 1920), but has also been shown to respond to physiological arousal during cognitive tasks (Beatty, 1982). For multiple cognitive functions, including memory and language processing, pupillometry has been employed as psycho-physiological index of cognitive load (Kahneman and Beaty, 1966; Beatty, 1982; Schluroff et al., 1986). In these experiments, task-evoked pupillary response (or simply pupillary response) is measured by comparing pupil dilation during an experimental task to a baseline measure of dilation immediately prior to task onset. In general, the pupils dilate as cognitive tasks become more difficult. This response has been linked to activity in the locus coeruleus (LC), which is a nucleus in the dorsal pons thought to regulate task engagement and attention, as well as other cortical and subcortical regions (Murphy et al., 2014; Alnaes, Sneve, Espeseth, van de Pavert and Laeng, 2014). Further, research on LC neurons in monkeys (Aston-Jones et al., 1999) has indicated two distinct modes of activation in the LC: tonic activity is believed to signal fatigue, while phasic activity signals cognitive or emotional processing (Granholm and Steinhauer, 2004). Phasic activity is thus of primary interest in speech recognition research, though it should be noted that the two modes of activity interact: if tonic activity is too low, subjects may be inattentive, and if tonic activity is too high, subjects may be distractible. In either case, subjects may not be able to exert large amounts of effort.

Several measures can be used to assess the pupillary response: mean dilation, peak dilation (or peak amplitude), and/or peak latency (i.e., the time between onset and peak pupil dilation). All three measures index cognitive load, although peak pupil dilation is typically used to identify the point of maximum load during an experimental trial, while mean dilation may be employed to assess how cognitive load is sustained across a given trial. Increasingly, pupillometry studies also use Growth Curve Analysis (GCA) to model the entire pupillary response curve and compare curves from different conditions. Using GCA for time course data can provide greater temporal resolution and quantify individual differences in a more meaningful way than traditional t-tests and ANOVAs (Mirman, 2014).

In the following sections, we provide an overview of studies that have used pupillometry specifically to assess cognitive load during adverse listening conditions. We focus on challenges associated with signal degradation (including the effect on cognitive load, fatigue, and attention, in respective order) and listener-related factors (including age and hearing loss). Talker-related challenges represent, to date, a virtually unexplored area in the use of pupillometry for speech recognition research.

3.1. Signal degradation

For young adults with normal hearing, pupillometry has been used to investigate how acoustic degradation of the speech signal may increase cognitive load. Zekveld et al. (2010) measured pupillary response during the perception of short, everyday phrases presented in stationary speech-shaped noise at three accuracy levels: 50%, 71%, and 84%. Results showed that peak pupil dilation, peak latency, and mean pupil dilation all systematically increased as the intelligibility of spoken sentences decreased, suggesting that reduced intelligibility imposes a greater cognitive load on listeners. Zekveld and Kramer (2014) extended these results with a larger range of performance levels and different noise conditions. Phrases were masked with a competing talker to create low-, medium-, and high-performance levels. The goal of the low-performance condition was to create a cognitive overload, for which the authors predicted listeners would give up and thus show a smaller pupillary response. The results supported this prediction, revealing decreases in peak pupil dilation as SNRs became extremely difficult. Pupillary response in the medium- and easy-performance conditions showed increasing dilation with decreasing intelligibility (as in Zekveld et al., 2010). Together, the results of these studies indicate that the relationship between intelligibility and cognitive load for speech-in-noise perception is systematic, but only within a limited range of difficulty.

An alternative method for degrading speech is to reduce spectral information using noise vocoding, which simulates the auditory quality of speech through cochlear implants (Shannon et al., 1995). Similar to Zekveld et al. (2010), in which pupillary response increased with decreasing speech intelligibility, Winn et al. (2015) found that pupillary response increased as spectral quality diminished. However, intelligibility by itself did not predict maximum pupil dilation. In fact, the effect of spectral quality was present even when the data was limited to correctly recalled trials. The authors concluded from these results that listeners may exert more or less effort during listening independent of the level of intelligibility.

Using pupillometry as a physiological index of cognitive load, therefore, can help identify processing differences even when behavioral results are similar (e.g., equivalent intelligibility levels). McGarrigle et al. (2017b) thus used pupillometry to show differences in cognitive effort for school-aged children listening to speech in an “ideal” SNR (+15 dB) and a “typical” classroom SNR (−2 dB), showing increased pupil dilation in the typical listening condition even though performance accuracy and response times did not differ across conditions.

Zekveld et al. (2014b) examined processing differences at a set intelligibility level (50%) by manipulating the similarity between target and masker. Similarity was modified in two ways: matched versus mismatched gender for target and masker, and spatial source separation. Differences in speakers’ gender and position both improved speech perception performance, but only gender affected the pupillary response, with mismatching gender resulting in lower cognitive load.

For energetic masking, competing speech, and noise-vocoding degradations, therefore, systematic relationships have been found between pupillary response and speech intelligibility or spectral quality; however, direct comparisons of these degradations also indicate variation in the cognitive load caused by each. Zekveld et al. (2014a) used pupillometry in tandem with fMRI for three difficult speech conditions: speech masked with modulated speech-shaped noise, speech masked with another talker, and noise-vocoded speech. Two intelligibility levels (50% and 84%) were presented for all speech types, along with two control conditions (silence and speech in quiet). Across conditions, increased neural activation was positively associated with peak pupil dilation, and activation was found in a number of brain areas that had previously been associated with peak pupil dilation, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. Activity in the cingulo-opercular attention network (which contains the dorsal anterior cingulate as well as the bilateral anterior frontal opercula) has been observed in other studies investigating degraded speech perception, and may be a key system for processing acoustically degraded speech (Peelle and Wingfield, 2016). Neural activity was also sensitive to degradation type, with competing speech eliciting greater activation of bilateral STG, bilateral medial temporal cortex, and the left middle temporal gyrus compared to noise-vocoded speech. Pupil data showed that speech masked by another talker elicited the greatest pupil dilation, followed first by the modulated noise masker, and then by the noise-vocoded speech. Together, the results suggest that pupillary response may be related to an increasing amount of overall neural activation. Further, the authors conclude that pupillary response may be an indirect indicator of activity in the cingulo-opercular attention network, although further research may be needed to rule out additional cortical attention networks that may respond in different experimental situations.

To begin to understand the relationship between self-reported effort and fatigue and pupillary response, McGarrigle et al. (2017a) used speech stimuli masked with multi-talker babble and a speech-picture verification task. For more difficult noise conditions (−8 dB SNR vs. +15 dB SNR), the authors predicted greater self-reported fatigue and effort, and a steeper post-peak decline in within-trial pupil size, especially for the second part of each experimental block.3 While self-reported effort ratings were significantly greater for the noisier condition, fatigue ratings were not. There was, as predicted, a steeper decrease in pupil size in the second half of difficult noise blocks compared to easy noise blocks. Thus, self-reported effort appeared to trend with pupillary response, but self-reported fatigue did not. In contrast, Wang et al. (2017) tracked pupillary response during a speech perception task with a single-talker masker, and compared peak pupil dilation to self-reported daily fatigue (as opposed to task-related fatigue, as in McGarrigle et al., 2017a). For both NH and HI listeners, self-reported daily fatigue was found to negatively predict peak pupil dilation—indicating that more fatigued individuals exerted less cognitive effort during the listening task.

In addition to noise, another factor that affects the pupillary response during speech recognition is switching attention between talkers: McCloy et al. (2017) manipulated the presence of reverberation (a cue to binaural location), the similarity between the target and competing talkers’ voices (i.e., either the same male talker or a female talker), and mid-trial attention switching (i.e., switch to a different talker or stay with the same talker). The trials in which participants switched their attention showed significantly greater pupillary response than those in which they maintained attention, but the manipulations of reverberation and talker type did not cause differences in pupillary response.

Pupillometry has also been employed to investigate factors that might reduce cognitive load during challenging speech perception. When speech is masked with competing speech, for example, cues to speaker location can assist the listener in identifying the target speech stream and improve recall performance (Kitterick et al., 2010). In a series of experiments, Koelewijn et al. (2015) thus manipulated talker location, speech onset, and target talker uncertainty to test their effects on pupillary response. The location of the two talkers (one male, one female) in modulated noise was either fixed or randomized between ears, and participants were instructed to recall the sentence of one or both of the talkers. Results showed a significant effect of location uncertainty on both peak pupil dilation and recall, but neither onset uncertainty nor talker uncertainty influenced pupillary response.

The findings from pupillometry studies on young adult listeners with normal hearing indicate that the pupillary response to linguistic stimuli is affected both by speech quality and by attentional cues. Moderate degradation of the speech signal caused by noise, competing talkers, and noise vocoding appears to systematically increase cognitive load; however, severe degradation elicits a smaller pupillary response, possibly due to individuals ‘giving up’ when overloaded by the cognitive demand of speech processing. Additionally, differences in pupillary response can occur independent of intelligibility depending on the type of speech degradation (e.g., energetic vs. informational masking). Lastly, switching attention between interlocutors and uncertainty about a target talker’s location both increase pupillary response.

3.2. Listener-related challenges: hearing impairment and aging

Using pupillometry in older adults can be problematic due to physiological changes, such as smaller pupil size and reduced range of dilation. To address this, Piquado et al. (2010) conducted two experiments with recall tasks to examine the effectiveness of pupillometry as a measure for younger and older adults with normal hearing. In the first experiment, participants listened to digit lists of varied lengths, and in the second experiment participants listened to sentences of manipulated lengths and syntactic complexities. Pupil size was normalized for each participant based on their personal pupil dilation range. Results showed that, for both younger and older adults, pupil size increased incrementally as the list items were presented. During the retention interval (i.e., the time between list presentation and recall), pupil sizes were significantly larger for longer lists, and older adults had an overall larger normalized pupil size than the young adults. In the second experiment, the younger adult group showed a significant effect of both sentence length and syntactic complexity, but the older adult group showed only an effect of sentence length. Together, the experiments provided evidence of an increase in cognitive load for both age groups as the length of input increased, but also indicated that syntactic challenge may only impose a differential cognitive load for younger adults.

To examine the effect of speech intelligibility on the pupillary response for older listeners, Zekveld et al. (2011) extended their 2010 methods to a middle-aged population with and without hearing loss. Mean pupil dilation, peak dilation, and peak latency decreased with increasing intelligibility level for both groups, but this decline was smaller for the hearing loss group than it was for the normal hearing group, suggesting that hearing impairment may lead to cognitive overload at higher SNRs (i.e., HI listeners max out at easier SNRs than NH listeners). Overall, listeners’ vocabulary was associated with greater pupillary response at the 50% and 84% intelligibility levels, suggesting that individuals with more cognitive resources may also utilize more resources during adverse listening conditions, thus resulting in greater pupil dilation.

Kuchinsky et al. (2013) examined the effect of orthographic lexical competition and noise masking on word identification, reaction time, and pupillary response in older adults with hearing loss. Participants were presented speech-in-noise stimuli at three SNRs: baseline (−2 to 0 dB, depending on the participant), easier (+2 dB from baseline), and harder (−2 dB from baseline). After hearing each item, participants made a forced-choice response from a visual array. In the competitor condition, the array included the target word, an onset or rhyme competitor, and two filler words; in the no-competitor condition, the array included the target and three filler words. Pupillary response was sensitive to both lexical competition and SNR: like the younger adults in Zekveld et al. (2010), older adults’ average pupil size was larger for the more difficult SNR, and the presence of lexical competition (as opposed to no lexical competition) resulted in greater average pupil size for the difficult SNR condition. Lexical competition was also found to adversely affect the ability to correctly identify words, and for correctly identified trials, reaction time was shown to be longer for the more difficult SNR.

The effect of speech perception training on pupil response for older adults with hearing loss was then assessed in Kuchinsky et al. (2014). Training took place over 8.5 weeks and involved listening to words in noise followed by auditory and visual feedback. Pupillary response, reaction time, and word recognition were all measured again, along with a number of cognitive skills (e.g., IQ, working memory, and vocabulary). For the training group, word recognition improved, post-training pupillary response peaked more rapidly, and average pupil size was larger. The authors concluded that trained participants may have been able to more rapidly discriminate speech-in-noise than control participants. Additionally, smaller vocabulary and greater hearing loss were associated with smaller peak pupil dilation. Similar to Zekveld et al. (2011), these results suggest that individuals with greater cognitive capacity may achieve better performance by exerting more cognitive effort.

For young adults, Zekveld et al. (2014a) found that speech masked by speech elicited greater pupillary response than speech masked with noise. Koelewijn et al. (2012) included age in an examination of this same effect. Using stationary noise, fluctuating noise, and a single-talker masker at two intelligibility levels (50% and 84%), they asked young and middle-aged adults to listen to sentence stimuli and repeat what they heard aloud. Again, the single-talker masker conditions elicited greater peak pupil dilation than the other two conditions (which did not significantly differ from one another), but no effect of age on pupillary response was found–supporting the conclusion that the effect of masker type on cognitive load is not dependent on age. Other studies, however have shown differences in cognitive load between NH and HI participants during adverse listening tasks (Koelewijn et al., 2014; Ohlenforst et al., 2017). Koelewijn et al. (2014), for example, examined the effects of hearing loss and masker type in middle-aged adults. They predicted that individuals with higher performance on cognitive skill measures (working memory capacity and inhibition) would have larger peak pupil dilations. This expectation was borne out, but only for the single-talker masker condition. Additionally, intelligibility and masker type affected peak pupil dilation, with single-talker masker eliciting larger pupillary response than a fluctuating noise masker. The authors concluded that informational masking may incur greater processing costs for listeners with hearing loss than it does for listeners with normal hearing.

Recently, pupillometry has also been used alongside other physiological measures of stress during speech recognition tasks. In a pilot study, Kramer et al. (2016) examined chromogranin A and cortisol saliva excretions (indices of psychological stress), which they predicted would pattern with pupillary response during speech-in-noise perception for adults with normal hearing and hearing loss. Two conditions were examined: speech-in-quiet (targeting 100% intelligibility), and speech-in-noise (targeting 50% intelligibility). Saliva samples were collected pre- and post-test as well as after each of the two blocks. Greater peak pupil dilation was found for the speech-in-noise condition than the speech-in-quiet condition for both groups, but this difference was significantly larger for the adults with normal hearing than for the adults with hearing loss, contrary to expectations. The authors noted that the participants with hearing loss rated the speech-in-noise as more effortful than the participants with normal hearing, indicating that a third factor, such as cognitive ability, may have impacted the results. Importantly, the three physiological measures—pupillometry, chromagranin A, and cortisol—were not similarly affected by either speech condition or hearing status.

3.3. Pupillometry summary

Like younger adults, older adults and populations with hearing loss appear to experience greater cognitive load as speech becomes less intelligible. Additional factors that have been posited to predict cognitive load include lexical competition, syntactic complexity, sentence length, and psychological stress. While lexical competition and sentence length have been shown to predict pupillary response in both younger and older adults, syntactic complexity appears to only predict pupillary response in younger adults so far. Additionally, measures of chromogranin A and cortisol do not appear to be predictive of pupillary response.

Notably, multiple studies indicate that individuals with better cognitive abilities exhibit a larger pupillary response during adverse listening conditions. The Framework for Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL) (Pichora-Fuller et al., 2016), which integrates the influences of motivation, attention, and fatigue on measures of listening effort (including pupil dilation) holds that individual listeners’ motivation and capacity for specific cognitive tasks is related the amount of cognitive effort expended during a task. Thus, a possible explanation for the abovementioned findings is that listeners with access to more cognitive resources take greater advantage of those resources, thereby increasing cognitive effort.

4. Looking forward

This article has reviewed the uses of eye tracking and pupillometry for studying challenges to speech recognition — challenges which can originate in signals, talkers, and listeners. Although both technologies have been used to address the online processing of speech in many difficult situations, there are also a number of everyday communication obstacles that have yet to be fully addressed with these methods: our lab, for example, is now assessing the efficacy of using pupillometry to investigate cognitive effort in the face of talker-related challenges such as unfamiliar accents.

Other researchers are beginning to combine these eye measurements with other physiological and neurophysiological measures. As described above, for example, Zekveld et al. (2014a) combined pupillometry with fMRI to investigate the neural correlates of listening effort, and Kramer et al. (2016) used it in conjunction with other physiological measures of stress. While eye tracking has also been combined with fMRI for word recognition in optimal listening conditions (Righi et al., 2010), the combination of eye tracking with neurophysiological measures has yet to be applied to speech recognition in the face of the challenges discussed in this paper. Such an approach would allow us to link the challenge-induced shifts in lexical activation and competition that have been observed in behavioral studies with the neural mechanisms underlying those processing changes.

In order to simultaneously investigate the direction of listeners’ attention and the cognitive load they experience during speech processing, some recent studies have also attempted to combine eye tracking and pupillometry. Ayasse et al. (2017) used both techniques in tandem to show that, although older adults’ eye movements to targets were just as fast as the younger adults’, this fast processing came at the cost of greater cognitive effort (i.e., a larger pupillary response). Wagner et al. (2016) also used the two methodologies together, showing with eye tracking that signal degradation slowed the disambiguation of phonologically similar words and delayed the use of semantic information, but also that early semantic integration could reduce the cognitive load associated with such disambiguation.

While combining eye tracking with pupillometry may provide insight into the relationship between cognitive effort and shifts in the dynamics of lexical activation and competition, a number of methodological challenges must be overcome to meaningfully combine the two methods. First, the VWP is used to study eye movements, but those movements are also problematic for making accurate pupil diameter measures. Thus, methods that can account for eye movement in pupil dilation measurement will be required before eye tracking and pupillometry can be used reliably together. Second, since the pupillary response is highly sensitive to changes in luminance (much more sensitive, in fact, than it is to changes in cognitive load), using it with visual tasks can be problematic, since any change in a visual array involves luminance shifts. One approach to this problem is to use simple, static visual displays along with baselining and normalization procedures. In Ayasse et al. (2017), for example, each participant’s minimum and maximum dilation were measured with white and black screens, and all subsequent measures were normalized according to their pupil size range (this was also intended to normalize across younger and older adult listeners, who differ in the dynamic range of the pupillary response). Then, by presenting the visual display for a period of time (e.g., 2s) before the onset of the auditory stimulus, researchers obtain a baseline dilation measure for a particular visual display and scale responses to auditory stimuli accordingly. The reliability of these normalization procedures, however, remains untested, and methods for scaling pupillary response data are inconsistent across studies. For studies that combine pupillometry with visual tasks and studies which use pupillometry alone, an important future step is to validate and standardize normalization and baseline correction methods.

Speech intelligibility measures, memory tasks, and subjective reports of listeners’ difficulty all provide critical information about the effects of various challenges on speech recognition. Eye tracking and pupillometry complement these offline methods by providing objective physiological measures of online cognitive processing during listening. They have provided evidence that cognitive effort can vary under different listening conditions even when speech is 100% intelligible, that lexical activation is slowed by challenging listening situations, and that the field of lexical competitors can change and be strengthened by difficult listening conditions. As we continue to refine these methods and their use in combination with other online measures, we will be better able to understand the challenges that listeners face and the mechanisms that allow them to overcome them.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant R01DC014281 from the National Institutes of Health/NIDCD.

Footnotes

Pupil dilation also changes in response to lighting (Reeves, 1920), stress (such as that caused by lying; Duñabeitia and Costa, 2015), and arousal (Hess and Polt, 1960).

For the purposes of this review, cognitive load is defined as “the extent to which the demands imposed by the task at a given moment consume the resources available to maintain successful task execution” (Pichora-Fuller et al., 2016, p. 12S).

Analysis of post-peak slope is less common in speech perception research (much more common are measures of mean dilation, peak dilation, and peak latency). McGarrigle et al. (2017a) argue that the steeper negative slope following peak pupil dilation is an indicator of greater listening-related fatigue. Their argument is in part based on the results of Hopstaken, van der Linden, Bakker, and Kompier (2015), which showed that overall pupillary response decreased across trial blocks for a mentally fatiguing 2-h study, and the assumption that a reduced state of arousal is reflective of fatigue.

References

- Allopenna PD, Magnuson JS, Tanenhaus MK, 1998. Tracking the time course of spoken word recognition using eye movements: evidence for continuous mapping models. J. Mem. Lang 38 (4), 419–439. 10.1006/jmla.1997.2558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alnaes D, Sneve MH, Espeseth T, van de Pavert SHP, Laeng B, 2014. Pupil size signals mental effort deployed during multiple object tracking and predicts brain activity in the dorsal attention network and locus coeruleus. J. Vis 14, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JE, Eisenband JG, Brown-Schmidt S, Trueswell JC, 2000. The rapid use of gender information: evidence of the time course of pronoun resolution from eye tracking. Cognition 76 (1), B13–B26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JE, Novick JM, Brown-Schmidt S, Eisenband JG, Trueswell J, 2001. Knowing the difference between girls and boys: the use of gender during online pronoun comprehension in young children. In: Proceedings of the 25th Annual boston university Conference on Language Development, pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JE, Fagnano M, Tanenhaus MK, 2003. Disfluencies signal theee, um, new information. J. Psycholinguist. Res 32 (1), 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JE, Tanenhaus MK, Altmann RJ, Fagnano M, 2004. The old and thee, uh, new: disfluency and reference resolution. Psychol. Sci 15 (9), 578–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JE, Kam CLH, Tanenhaus MK, 2007. If you say thee uh you are describing something hard: the on-line attribution of disfluency during reference comprehension. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cognit 33 (5), 914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam S, 2016. A new experimental paradigm to study children’s processing of their parent’s unscripted language input. J. Mem. Lang 88, 104–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Cohen J, 1999. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biol. psychiatry 46 (9), 1309–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayasse ND, Lash A, Wingfield A, 2017. Effort not speed characterizes comprehension of spoken sentences by older adults with mild hearing impairment. Front. aging Neurosci 8, 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KG, Ferreira F, 2007. The Processing of Filled Pause Disfluencies in the Visual World. Eye Movements: a Window on Mind and Brain, pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty J, 1982. Task-evoked pupillary responses, processing load, and the structure of processing resources. Psychol. Bull 91 (2), 276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David BM, Chambers CG, Daneman M, Pichora-Fuller MK, Reingold EM, Schneider BA, 2011. Effects of aging and noise on real-time spoken word recognition: evidence from eye movements. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res 54 (1), 243–262. 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0233). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow AR, Bent T, 2008. Perceptual adaptation to non-native speech. Cognition 106 (2), 707–729. 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breheny R, Ferguson HJ, Katsos N, 2013. Investigating the timecourse of accessing conversational implicatures during incremental sentence interpretation. Lang. Cognit Process 28 (4), 443–467. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer S, Bradlow AR, 2016. The temporal dynamics of spoken word recognition in adverse listening conditions. J. Psycholinguist. Res 45 (5), 1151–1160. 10.1007/s10936-015-9396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer S, Mitterer H, Huettig F, 2012. Speech reductions change the dynamics of competition during spoken word recognition. Lang. Cognit Process 27 (4), 539–571. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer S, Mitterer H, Huettig F, 2013. Discourse context and the recognition of reduced and canonical spoken words. Appl. Psycholinguist 34 (3), 519–539. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CG, Tanenhaus MK, Magnuson JS, 2004. Actions and affordances in syntactic ambiguity resolution. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cognit 30 (3), 687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CM, Garrett MF, 2004. Rapid adaptation to foreign-accented English. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 116 (6), 3647–3658. 10.1121/1.1815131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayards M, Tanenhaus MK, Aslin RN, Jacobs RA, 2008. Perception of speech reflects optimal use of probabilistic speech cues. Cognition 108 (3), 804–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RM, 1974. The control of eye fixation by the meaning of spoken language: a new methodology for the real-time investigation of speech perception, memory, and language processing. Cogn. Psychol 6 (1), 84–107. 10.1016/0010-0285(74)90005-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins K,A,Q, Dar H, Wingfield A, Miller P, 2014. Acoustic masking disrupts time-dependent mechanisms of memory encoding in word-list recall. Mem. Cognit 42, 622–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan D, Gaskell MG, 2007. The temporal dynamics of ambiguity resolution: evidence from spoken-word recognition. J. Mem. Lang 57 (4), 483–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan D, Magnuson JS, Tanenhaus MK, 2001. Time course of frequency effects in spoken-word recognition: evidence from eye movements. Cogn. Psychol 42 (4), 317–367. 10.1006/cogp.2001.0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan D, Tanenhaus MK, Chambers CG, 2002. Accent and reference resolution in spoken-language comprehension. J. Mem. Lang 47 (2), 292–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan D, Drucker SJ, Scarborough RA, 2008. Talker adaptation in speech perception: adjusting the signal or the representations? Cognition 108 (3), 710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duñabeitia JA, Costa A, 2015. Lying in a native and foreign language. Psychon Bull. Rev 22 (4), 1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt PE, Bailey KG, Ferreira F, 2006. Do speakers and listeners observe the gricean maxim of quantity? J. Mem. Lang 54 (4), 554–573. [Google Scholar]

- Van Engen KJ, Peelle JE, 2014. Listening effort and accented speech. Front. Hum. Neurosci 8, 577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, Gagne J-P, Alepins M, Dubois P, 2010. Evaluating the effort expended to understand speech in noise using a dual-task paradigm: the effects of providing visual speech cues. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res 53 (1), 18–33. 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0140). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin PA, Gagne J-P, 2011. Older adults expend more listening effort than young adults recognizing speech in noise. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res 54 (3), 944–958. 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0069). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Steinhauer SR, 2004. Pupillometric measures of cognitive and emotional processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol 52 (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodner D, Sedivy JC, 2011. The effect of speaker-specific information on pragmatic inferences. In: The Processing and Acquisition of Reference, vol. 239, p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Grodner DJ, Klein NM, Carbary KM, Tanenhaus MK, 2010. “Some,” and possibly all, scalar inferences are not delayed: evidence for immediate pragmatic enrichment. Cognition 116 (1), 42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanulíková A, Weber A, 2012. Sink positive: linguistic experience with th sub-stitutions influences nonnative word recognition. Atten. Percept. Psychophys 74 (3), 613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich A, Schneider BA, 2011. Elucidating the effects of ageing on remembering perceptually distorted word pairs. Q. J. Exp. Psychol 64, 186–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer KS, Staub A, 2014. Competing speech perception in older and younger adults. Ear Hear. 35 (2), 161–170. 10.1097/aud.0b013e3182a830cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller D, Grodner D, Tanenhaus MK, 2008. The role of perspective in identifying domains of reference. Cognition 108 (3), 831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess EH, Polt JM, 1960. Pupil size as related to interest value of visual stimuli. Science 132 (3423), 349–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks CB, Tharpe AM, 2002. Listening effort and fatigue in school-age children with and without hearing loss. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res 45 (3), 573–584. 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/046). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopstaken JF, van der Linden D, Bakker AB, Kompier MA, 2015. The window of my eyes: task disengagement and mental fatigue covary with pupil dynamics. Biol. Psychol 110, 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Snedeker J, 2009a. Semantic meaning and pragmatic interpretation in 5-year-olds: evidence from real-time spoken language comprehension. Dev. Psychol 45 (6), 1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Snedeker J, 2009b. Online interpretation of scalar quantifiers: insight into the semantics–pragmatics interface. Cogn. Psychol 58 (3), 376–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Snedeker J, 2013. The use of lexical and referential cues in children’s online interpretation of adjectives. Dev. Psychol 49 (6), 1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettig F, Altmann GTM, 2005. Word meaning and the control of eye fixation: semantic competitor effects and the visual world paradigm. Cognition 96 (1), B23–B32. 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettig F, Rommers J, Meyer AS, 2011. Using the visual world paradigm to study language processing: a review and critical evaluation. Acta Psychol. 137 (2), 151–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Speer SR, 2008. Anticipatory effects of intonation: eye movements during instructed visual search. J. Mem. Lang 58 (2), 541–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Beatty J, 1966. Pupil diameter and load on memory. Science 154 (3756), 1583–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Trueswell JC, 2008. Interpreting pronouns and demonstratives in Finnish: evidence for a form-specific approach to reference resolution. Lang. Cognit Process 23 (5), 709–748. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Runner JT, Sussman RS, Tanenhaus MK, 2009. Structural and semantic constraints on the resolution of pronouns and reflexives. Cognition 112 (1), 55–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitterick PT, Bailey PJ, Summerfield AQ, 2010. Benefits of knowing who, where, and when in multi-talker listening. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 127, 2498–2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelewijn T, Zekveld AA, Festen JM, Kramer SE, 2012. Pupil dilation uncovers extra listening effort in the presence of a single-talker masker. Ear Hear. 33 (2), 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelewijn T, Zekveld AA, Festen JM, Kramer SE, 2014. The influence of informational masking on speech perception and pupil response in adults with hearing impairment. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 135 (3), 1596–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelewijn T, de Kluiver H, Shinn-Cunningham BG, Zekveld AA, Kramer SE, 2015. The pupil response reveals increased listening effort when it is difficult to focus attention. Hear. Res 323, 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer SE, Teunissen CE, Zekveld AA, 2016. Cortisol, chromogranin A, and pupillary responses evoked by speech recognition tasks in normally hearing and hard-of-hearing listeners: a pilot study. Ear Hear. 37, 126S–135S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinsky SE, Ahlstrom JB, Vaden KI, Cute SL, Humes LE, Dubno JR, Eckert MA, 2013. Pupil size varies with word listening and response selection difficulty in older adults with hearing loss. Psychophysiology 50 (1), 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinsky SE, Ahlstrom JB, Cute SL, Humes LE, Dubno JR, Eckert MA, 2014. Speech-perception training for older adults with hearing loss impacts word recognition and effort. Psychophysiology 51 (10), 1046–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurumada C, Brown M, Bibyk S, Pontillo DF, Tanenhaus MK, 2014. Is it or isn’t it: listeners make rapid use of prosody to infer speaker meanings. Cognition 133 (2), 335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffel T, Xiang M, Kennedy C, 2016. Imprecision is pragmatic: evidence from referential processing. In: Semantics and Linguistic Theory, vol. 26, pp. 836–854. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson JS, Dixon JA, Tanenhaus MK, Aslin RN, 2007. The dynamics of lexical competition during spoken word recognition. Cognit Sci. 31 (1), 133–156. 10.1080/03640210709336987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marslen-Wilson WD, 1987. Functional parallelism in spoken word-recognition. Cognition 25 (1), 71–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland JL, Elman JL, 1986. The TRACE model of speech perception. Cogn. Psychol 18 (1), 1–86. 10.1016/0010-0285(86)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloy DR, Lau BK, Larson E, Pratt KA, Lee AK, 2017. Pupillometry shows the effort of auditory attention switching a. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 141 (4), 2440–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SL, Tun PA, Cox LC, Colangelo M, Stewart R, Wingfield A, 2005. Hearing loss and perceptual effort: downstream effects on older adults’ memory for speech. Q. J. Exp. Psychol 58, 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarrigle R, Dawes P, Stewart AJ, Kuchinsky SE, Munro KJ, 2017a. Pupillometry reveals changes in physiological arousal during a sustained listening task. Psychophysiology 54 (2), 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarrigle R, Dawes P, Stewart AJ, Kuchinsky SE, Munro KJ, 2017b. Measuring listening-related effort and fatigue in school-aged children using pupillometry. J. Exp. Child Psychol 161, 95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Tanenhaus MK, Aslin RN, 2002. Gradient effects of within-category phonetic variation on lexical access. Cognition 86, B33–B42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Clayards MA, Tanenhaus MK, Aslin RN, 2008. Tracking the time course of phonetic cue integration during spoken word recognition. Psychon Bull. Rev 15 (6), 1064–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Farris-Trimble A, Seedorff M, Rigler H, 2016. The effect of residual acoustic hearing and adaptation to uncertainty on speech perception in cochlear implant users: evidence from eye tracking. Ear Hear. 37 (1), e37–e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Farris-Trimble A, Rigler H, 2017. Waiting for lexical access: cochlear implants or severely degraded input lead listeners to process speech less incrementally. Cognition 169, 147–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen JM, Huettig F, 2012. Changing only the probability that spoken words will be distorted changes how they are recognized. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 131 (1), 509–517. 10.1121/1.3664087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen JM, Viebahn MC, 2007. Tracking recognition of spoken words by tracking looks to printed words. Q. J. Exp. Psychol 60 (5), 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirman D, 2014. Growth Curve Analysis and Visualization Using R: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Stenfelt S, Lunner T, Rönnberg J, Rudner M, 2014. Cognitive spare capacity in older adults with hearing loss. Front. Aging Neurosci 6, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PR, O’Connell RG, O’Sullivan M, Robertson IH, Balsters JH, 2014. Pupil diameter covaries with BOLD activity in human locus coeruleus. Hum. Brain Mapp 35, 4140–4154. 10.1002/hbm.22466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng EHN, Rudner M, Lunner T, Pedersen MS, Rönnberg J, 2013. Effects of noise and working memory capacity on memory processing of speech for hearing-aid users. Int. J. Audiol 52 (7), 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris D, 1994. Shortlist: a connectionist model of continuous speech recognition. Cognition 52 (3), 189–234. 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90043-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlenforst B, Zekveld AA, Lunner T, Wendt D, Naylor G, Wang Y, Kramer SE, 2017. Impact of stimulus-related factors and hearing impairment on listening effort as indicated by pupil dilation. Hear. Res 351, 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizza D, Huang YT, Chierchia G, Snedeker J, 2009, September Relevance of polarity for the online interpretation of scalar terms. In: Semantics and Linguistic Theory, vol. 19, pp. 360–378. [Google Scholar]

- Peelle JE, 2018. Listening effort: how the cognitive consequences of acoustic challenges are reflected in brain and behavior. Ear Hear. 39 (2), 204–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelle JE, Wingfield A, 2016. The neural consequences of age-related hearing loss. Trends Neurosci. 39 (7), 486–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichora-Fuller MK, Kramer SE, Eckert MA, Edwards B, Hornsby BW, Humes LE, Naylor G, 2016. Hearing impairment and cognitive energy: the framework for understanding effortful listening (FUEL). Ear Hear. 37, 5S–27S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picou EM, Ricketts TA, 2014. The effect of changing the secondary task in dual-task paradigms for measuring listening effort. Ear Hear. 35 (6), 611–622. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picou EM, Ricketts TA, Hornsby BWY, 2013. How hearing aids, background noise, and visual cues influence objective listening effort. Ear Hear. 34 (5), e52–e64. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31827f0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquado T, Isaacowitz D, Wingfield A, 2010. Pupillometry as a measure of cognitive effort in younger and older adults. Psychophysiology 47 (3), 560–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquado T, Benichov JI, Brownell H, Wingfield A, 2012. The hidden effect of hearing acuity on speech recall, and compensatory effects of self-paced listening. Int. J. Audiol 51, 576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp R, Mimpen AM, 1979. Improving the reliability of testing the speech reception threshold for sentences. Audiology 18 (1), 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porretta V, Tucker BV, Järvikivi J, 2016. The influence of gradient foreign accentedness and listener experience on word recognition. J. Phon 58, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt J, Dodd M, Welsh T, 2006. Growing older does not always mean moving slower: examining aging and the saccadic motor system. J. Mot. Behav 38, 373–382. 10.3200/JMBR.38.5.373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt PMA, 1968. Channel capacity, intelligibility and immediate memory. Q. J. Exp. Psychol 20, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt P, 1991. Mild hearing loss can cause apparent memory failures which increase with age and reduce with IQ. Acta oto-laryngologica 111 (Suppl. 476), 167e–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves P, 1920. The response of the average pupil to various intensities of light. JOSA 4 (2), 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch E, Weber A, 2012. Adapting to suprasegmental lexical stress errors in foreign-accented speech. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 132 (2), 1165–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revill KP, Spieler DH, 2012. The effect of lexical frequency on spoken word recognition in young and older listeners. Psychol. Aging 27 (1), 80–87. 10.1037/a0024113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righi G, Blumstein SE, Mertus J, Worden MS, 2010. Neural systems underlying lexical competition: an eye tracking and fMRI study. J. Cognit Neurosci 22 (2), 213–224. 10.1162/jocn.2009.21200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salverda AP, Dahan D, McQueen JM, 2003. The role of prosodic boundaries in the resolution of lexical embedding in speech comprehension. Cognition 90 (1), 51–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarampalis A, Kalluri S, Edwards B, Hafter E, 2009. Objective measures of listening effort: effects of background noise and noise reduction. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res 52 (5), 1230–1240. 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0111). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluroff M, Zimmermann TE, Freeman RB, Hofmeister K, Lorscheid T, Weber A, 1986. Pupillary responses to syntactic ambiguity of sentences. Brain Lang. 27 (2), 322–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz F, 2014. Presuppositions are fast, whether hard or soft-evidence from the visual world. In: Semantics and Linguistic Theory, vol. 24, pp. 1e–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sedivy JC, Tanenhaus MK, Chambers CG, Carlson GN, 1999. Achieving incremental semantic interpretation through contextual representation. Cognition 71 (2), 109–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV, Zeng F, Kamath V, Wygonski J, Ekelid M, 1995. Speech recognition with primarily temporal cues. Science 270, 303–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoorenburg GF, 1992. Speech reception in quiet and noisy conditions by individuals with noise-induced hearing loss in relation to their tone audiogram. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 91, 421–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedeker J, Trueswell JC, 2004. The developing constraints on parsing decisions: the role of lexical-biases and referential scenes in child and adult sentence processing. Cogn. Psychol 49 (3), 238–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant AM, 1999. The effect of noise on memory for spoken syllables. Int. J. Psychol 34 (5–6), 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant AM, 2007. Effects of noise on identification and serial recall of nonsense syllables in older and younger adults. Aging, Neuropsychol, Cognit 14 (2), 126–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Spivey-Knowlton MJ, Eberhard KM, Sedivy JC, 1995. Integration of visual and linguistic information in spoken language comprehension. Science 1632–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueswell J, Gleitman L, 2004. Children’s eye movements during listening: developmental evidence for a constraint-based theory of sentence processing. In: The Interface of Language, Vision, and Action: Eye Movements and the Visual World, pp. 319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Trueswell JC, Sekerina I, Hill NM, Logrip ML, 1999. The kindergarten-path effect: studying on-line sentence processing in young children. Cognition 73 (2), 89–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A, Pals C, de Blecourt CM, Sarampalis A, Baskent D, 2016. Does signal degradation affect topedown processing of speech? In: Physiology, Psychoacoustics and Cognition in Normal and Impaired Hearing. Springer, Cham, pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Naylor G, Kramer SE, Zekveld AA, Wendt D, Ohlenforst B, Lunner T, 2018. Relations between self-reported daily-life fatigue, hearing status, and pupil dilation during a speech perception in noise task. Ear Hear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DG, Tanenhaus MK, Gunlogson CA, 2008. Interpreting pitch accents in online comprehension: H* vs. Lþ H. Cognit Sci. 32 (7), 1232–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Cutler A, 2004. Lexical competition in non-native spoken-word recognition. J. Mem. Lang 50 (1), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Scharenborg O, 2012. Models of spoken-word recognition. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cognit Sci 3 (3), 387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Grice M, Crocker MW, 2006. The role of prosody in the interpretation of structural ambiguities: a study of anticipatory eye movements. Cognition 99 (2), B63–B72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MB, Edwards JR, Litovsky RY, 2015. The impact of auditory spectral resolution on listening effort revealed by pupil dilation. Ear Hear. 36 (4), e153–e165. 10.1097/aud.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter L, Gorman KS, Tanenhaus MK, 2011. Scalar reference, contrast and discourse: separating effects of linguistic discourse from availability of the referent. J. Mem. Lang 65 (3), 299–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zekveld AA, Kramer SE, 2014. Cognitive processing load across a wide range of listening conditions: insights from pupillometry. Psychophysiology 51 (3), 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zekveld AA, Kramer SE, Festen JM, 2010. Pupil response as an indication of effortful listening: the influence of sentence intelligibility. Ear Hear. 31 (4), 480–490. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181d4f251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]