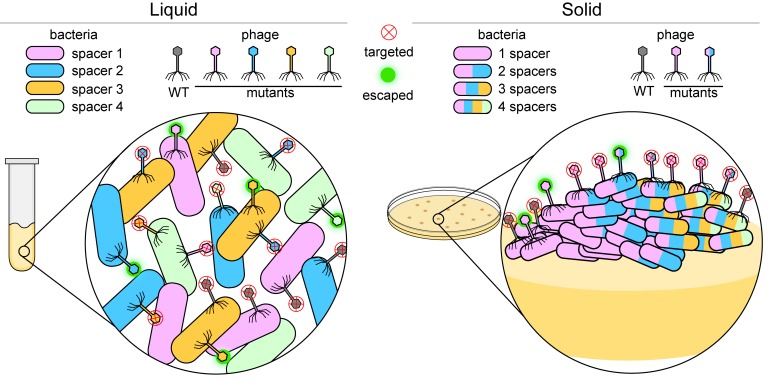

Figure 1. Bacteria versus viruses called phages.

To defend themselves against phages, bacteria (colored capsules) acquire a region of a phage genome and insert it into their own genome as a 'spacer'. When growing in a liquid environment (left), individual bacterial cells usually acquire a single spacer that targets just one region of the wild-type (WT) phage (shown in grey). In the figure, each bacterial cell has one of four different spacers (shown in blue, green, orange and pink). However, phages mutate in an effort to bypass these defenses: a mutation in the region of the phage genome corresponding to, say, a blue spacer means that the phage can attack and escape the defense of bacteria with blue spacers (fuzzy green circle), but not bacteria with green, orange or pink spacers (red X inside a circle). When growing on a solid surface (right), if an individual cell acquires, say, a pink spacer, it will go on to form a colony of phage resistant cells (inset). If a phage gains a mutation in the region targeted by the pink spacer, the phage will escape detection. In order to stay protected, some bacterial cells within the colony acquire multiple spacers (multi-colored bacterial cells) and can fight off various mutant phages.

Image credit: Dipali Sashital (CC BY 4.0)