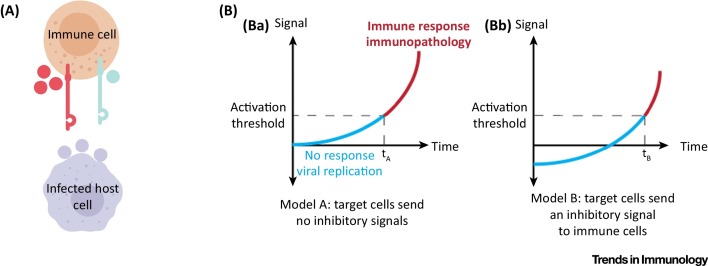

Figure 2.

Using a Shared Ligand as a Cellular Entry Receptor Is Advantageous for Pathogens. (A) Evolutionary pressure favours viruses that use the shared ligands of paired receptors as entry and/or adhesion receptors. Host cells that express a shared ligand (shown in purple) are relatively protected from immune system attack because the shared ligand sends a dominant inhibitory signal to immune cells expressing the paired inhibitory (marked in red) and coactivating (marked in black) receptors. Therefore, viruses that enter and reproduce in cells expressing a shared ligand can avoid an immune response. Virus-infected host cells that do not express a shared ligand can be killed by the immune system. (B) Invading a host cell that sends an inhibitory signal to immune cells allows pathogens more time to replicate safely. (Ba) A host cell sends no net signal to the immune system at the initiation of the pathological process (t = 0). This is true of several cell types, such as beta cells in the pancreas as well as some cells in immune privileged sites throughout the body. The time that the host cell takes to produce a signal that is sufficient to activate immune cells is termed tA. (Bb) If the host cell sends an inhibitory signal to the immune system at baseline (through its expression of a shared ligand), then the same processes that induce immune-activating signals will take longer to cross the threshold required to activate the immune system (tB > tA). This lag period (tB − tA) allows for greater viral replication and increased pathology to develop before immune intervention (blue portion of the graph). In turn, the larger viral population is more likely to survive immune attack. Onset of immunopathology is indicated by the red portion of the graph.