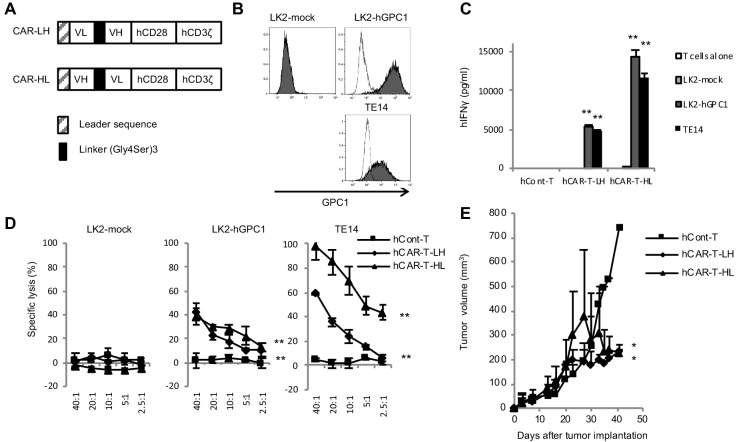

Figure 2. GPC1-specific human hCAR-T cells specifically recognized hGPC1-positive tumor cells and inhibited tumor growth in xenograft mouse model.

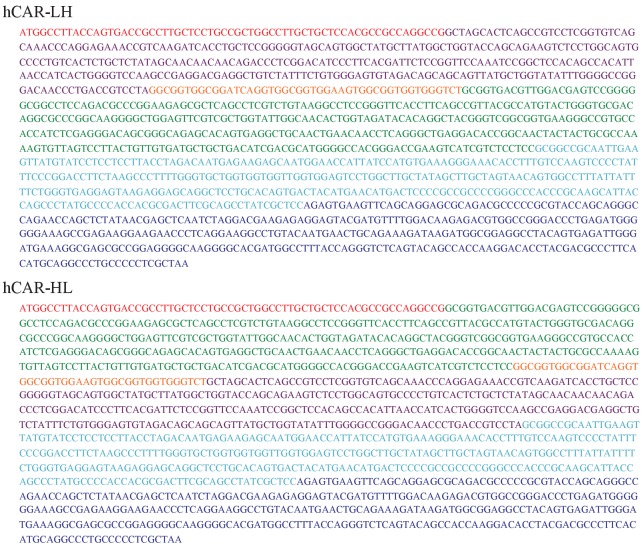

(A) Diagrams of GPC1-specific human hCAR; scFv frgments derived from light chain (VL) and heavy chain (VH) of anti-GPC1 mAb (clone: 1–12) were fused to human CD28 and human CD3ζ signal domains. The positions of VL and VH were switched to generate two forms of CAR gene, LH and HL. (B) LK2-hGPC1, LK2-mock, and endogenous hGPC1-expressing TE14 were stained by anti-GPC1 mAb (clone: 1–12) (shaded histogram) or isotype control (open histogram). (C) GPC1-specific IFNγ secretion of hCAR-T cells (LH or HL form) or hCont-T cells co-cultured with LK2-mock, LK2-hGPC1, or TE14. (D) Antigen-specific in vitro cytotoxicity of hCAR-T cells (LH or HL form) or hCont-T cells against LK2-hGPC1, LK2-mock, or TE14 was evaluated by using standard Cr51 releasing assay. (E) hCAR-T cells (LH or HL form) or hCont-T cells (2 × 107 cells/mouse) were injected into TE14-bearing NOG mice on day 9. Results are representative of two or three experiments. Error bars indicate SD.