Abstract

This study explored the effect of methyl-indole on pancreatic cancer cell viability and investigated the mechanism involved. The viability of pancreatic cells showed a significant suppression on treatment with methyl-indole in dose-based manner. Treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole suppressed Capan-1 cell viability to 23%. The viability of Aspc-1 cells was reduced to 20% and those of MIApaCa-2 cells to 18% by 5 µM methyl-indole. The apoptotic proportion of Capan-1 cells was 67%, while as those of Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells increased to 72 and 77%, respectively, on treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole. The level of P13K, p-Tyr, p-Crkl and p-Akt was inhibited in the cells by methyl-indole. Moreover, methyl-indole also suppressed zinc-finger protein, X-linked mRNA and protein expression in tested cells. In summary, methyl-indole exhibits anti-proliferative effect on pancreatic cancer cells and induces apoptosis. It targeted ZFX expression and down-regulated P13K/AKT pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Therefore, methyl-indole acts as therapeutic agent for pancreatic cancer and may be studied further.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Methyl-indole, Zinc finger print protein, Apoptosis

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is responsible for 3.2% cases among newly detected carcinoma patients and accounts for 7.5% deaths linked to cancers in USA as per Cancer statistics of 2019 (Siegel et al. 2019). It has worst prognosis among all cancer types which is evident by survival rate of only 9% for pancreatic cancer patients (Siegel et al. 2019). Multiple factors like diagnosis at late stage in high proportion of people, very low response to therapies and poor prognosis are the contributing factors for low survival rate of pancreatic cancer patients (Ryan et al. 2014). The malignant cells are unable to express differentiated characteristics of normal pancreatic cells and undergo rapid invasion to the tissues in surroundings (Höhne et al. 1992). Recent studies demonstrated infiltration of the T cells into tumor environment as the prognostic factor (Carstens et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2016). Therapies involving blockade of various immune checkpoints have been used for cancer treatment but had lackluster success for the treatment of pancreatic cancer (Le et al. 2013). The chromosome-X in the mammalian genome contains a zinc-finger gene known as X-linked (ZFX) gene (Harel et al. 2012). It is a transcription regulatory gene which maintains growth of stem cells associated with embryonic as well as hematopoietic tissues (Harel et al. 2012). The tumorigenesis of many cancers like pulmonary, glioma, breast cancer and leukemia is chiefly regulated by ZFX expression (Yang et al. 2014; Weisberg et al. 2014). It is reported that elevation of ZFX expression in hepatocellular cancer cells is associated with development of resistance to drugs (Zhang et al. 2016). The ZFX has been demonstrated to be linked with the cellular proliferation and chemotherapeutic resistance in myeloid leukemia cells (Wu et al. 2016).

The indole derivatives like indolequinone have shown potent inhibitory effect on pancreatic carcinoma cell growth (Dehn et al. 2006). The NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 inhibition by indolequinone was found to be responsible for cytotoxicity in pancreatic carcinoma cells (Winski et al. 2001). Growth inhibition via NQO1 down-regulation in pancreatic carcinoma cells was also observed on treatment with dicumarol (Lewis et al. 2004). The current study explored the effect of methyl-indole on Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell viability and investigated the mechanism involved.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

The cell lines Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 were provided by the Cell Bank for culture and collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The culture of cells was carried out in RPMI-1640 medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) which contained 10% fetal bovine serum. The mixture of penicillin (100 U/ml) along with streptomycin (100 µg/ml) was added to medium and incubation was done at 37 ˚C under 95% air and 5% CO2.

Transfection

The primer sequence of ZFX was subjected to cloning in peGFP-C1 expression plasmid after amplification. Then, electroporation technique was used for transfection of empty vector or the peGFP-c1–ZFX plasmid into the cells using Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II (Bio-rad laboratories, inc.). The transfection was carried out at a voltage of 250 v and electricity capacity of 950 µFd. The cells were then re-suspended in RPMI-1640 medium and culture was performed for 48 h at 37 ˚C.

Cell proliferation assay

The methyl-indole-mediated altered viability of pancreatic cancer cells was measured by MTT assay. The cell lines in 96-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/well concentration were maintained for 24 h in RPMI-1640 medium. Treatment with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 µM methyl-indole for 48 h was followed by addition of MTT and incubation for 4 h. Medium was discarded and cells treated with DMSO to record optical density in plate reader at 490 nm wavelength.

Determination of colony formation

The methyl-indole-treated cells were subjected to culture using a double-layered soft agar system for colony formation analysis. The cellular suspension after washing with RPMI-1640 medium was put at 1 × 104 cells/ml concentration in 12-well plates. The cellular feeder layer was obtained by equilibration at a temperature of 42 ˚C. The cellular incubation was performed for 10 days followed by examination of colonies using inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Apoptotic assay

The methyl-indole-induced apoptotic changes were determined by flow cytometry of the Annexin V/FITC stained cells. The cells treated with methyl-indole (5.0 µM) for 48 h were harvested and incubated in HEPES binding buffer. Subsequently, staining was carried out using Annexin V/FITC kit and propidium iodide (5 mg/ml) for 20 min at room temperature in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Analysis of cellular samples for apoptosis was made using FACSCanto™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Cell cycle analysis

The cells in six-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well concentration were treated for 48 h with methyl-indole (5.0 µM). The cells washed were collected and then fixing was performed in 70% ethyl alcohol for overnight at 4 ˚C. Treatment of cells with tris-hydrochloric acid buffer (pH 7.3) mixed with 1% RNase A was followed by propidium iodide (5 mg/ml) dyeing. The DNA content in the cells was detected using flow cytometry.

Western blot analysis

The cells treated with methyl-indole (5.0 µM) were lysed on incubation with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Concentration of proteins was measured in lysates by bicinchoninic acid assay and then resolved on 8–10% SDS-Page. Transfer of proteins to PVDF membranes and then incubation with 5% skim milk were carried out for 2 h. The proteins were probed by incubation of membranes with anti-ZFX (Catalog number PA5-78234; dilution 1:1200; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-AKT (Catalog number SAB4500799; dilution 1:1200; Merck), anti-PI3K (catalog number GW21071; dilution 1:1200; Merck) and anti-β-actin (A1978; dilution 1:1200; Merck) antibodies at 4 ˚C for overnight. The membrane washing and subsequent incubation with secondary goat anti-mouse antibodies were carried out at room temperature for 3 h. The ECL reagent (Beyotime institute of Biotechnology) was used for blot detection and image lab software (Bio-rad laboratories, inc.) for data analysis.

Reverse transcription‑quantitative PCR

The RNA isolation from methyl-indole (5.0 µM)-treated cells was made by Trizol® (invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The FastQuant RT kit (Tiangen Biotech co., ltd.) was employed for reverse transcription of the RNA samples. The PCR was carried out with Superreal PreMix Plus (Tiangen Biotech co., ltd.) in combination with PCR detection System (roche Molecular Systems, inc.). The qPCR consisted of 5 min at 94 ˚C and then 39 cycles for 8 s at 94 ˚C, for 15 s at 63 ˚C and for 25 s at 70 ˚C. The sequences used were: ZFX, forward 5′-GGC AGT CCA CAG CAA GAA C-3′, reverse 5′-TTG GTA TCC GAG AAA GTCA GAA G-3′; β-actin, forward 5′-CTCC ATC CT GGCC TC GCT GT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCT GTC ACC TTC ACC GTT CC-3′. The average threshold cycle values were subjected to normalization with GAPDH and relative expression levels were quantified according to the 2−ΔΔCq method.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed statistically by SPSS 19.0 software (IBM corp.) and presented values are mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. The differences were statistically determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test and Student’s t test. The experiments were conducted three times independently and P < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistically significant difference (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Structure of methyl-indole

Results

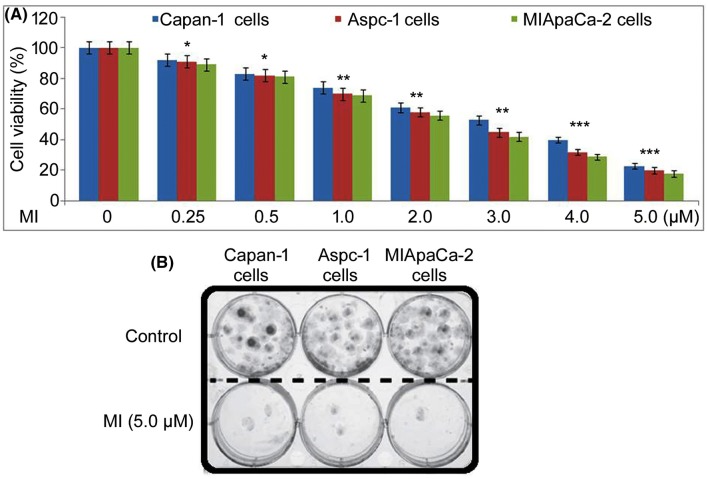

Methyl-indole suppresses Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cell viability

Methyl-indole-mediated changes in pancreatic cell viability were measured by MTT assay (Fig. 2a). Methyl-indole showed cytotoxicity for Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Treatment with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 µM methyl-indole decreased Capan-1 cell viability to 92, 83, 74, 61, 53, 40 and 23%, respectively, at 48 h. The Aspc-1 cellular viability was 91, 82, 70, 58, 45, 32 and 20%, respectively, in 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 µM methyl-indole-treated cultures. In MIApaCa-2 cells, viability was 89, 81, 69, 56, 42, 29 and 18%, respectively, on treatment with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 µM methyl-indole. In 5.0 µM methyl-indole-treated cells, colony forming ability was significantly reduced compared to control (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Effect of methyl-indole on pancreatic cell viability. a The methyl-indole treatment of Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells at 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 µM was followed by determination of viability changes using MTT assay. b Inverted microscopy was used for detection of colony formation in Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.005 vs. 0 µM methyl-indole

Methyl-indole has apoptotic effect on pancreatic cells

In pancreatic cells, methyl-indole enhanced apoptotic rate significantly relative to untreated cells (Fig. 3). The apoptotic rate in Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells was detected on treatment with 5.0 µM methyl-indole at 48 h. In Capan-1 cells apoptosis was increased to 67% on treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole relative to 2.11% in control. The apoptosis in 5 µM methyl-indole-treated Aspc-1 cells increased to 72% relative to 2.37% in control. Similarly, 5 µM methyl-indole treatment enhanced MIApaCa-2 cell apoptosis to 77% compared to 2.89% in control.

Fig. 3.

Effect of methyl-indole on apoptosis in pancreatic cells. The Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells were treated with 5 µM or 0 µM methyl-indole for 48 h. Annexin V/FITC kit and PI (5 µl) stained cells were detected for apoptosis using FACSCanto™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences)

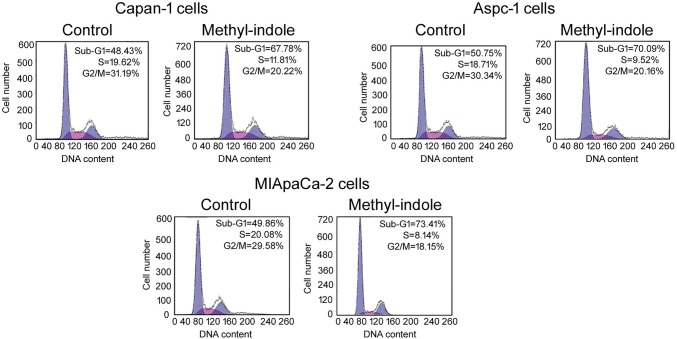

Methyl-indole inhibits cell cycle progression

Methyl-indole-mediated changes in distribution of cells in cell cycle phases were analyzed by flow cytometric assay (Fig. 4). The peak for sub-G1 cells showed significant increase in 5 µM methyl-indole-treated cells relative to untreated control. However, the peaks for S and G2/M phases were reduced by 5 µM methyl-indole in Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells. This data proved arrest of cell cycle by methyl-indole in sub-G1 in pancreatic cells.

Fig. 4.

Effect of methyl-indole on cell cycle. The Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells were treated with 5 µM or 0 µM methyl-indole for 48 h. Then, DNA content distribution in the cells was detected by flow cytometry

Methyl-indole inhibits p-Tyr and p-Crkl expression

Changes in p-Tyr and p-Crkl expression by methyl-indole in pancreatic cells were detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 5). In Capan-1 cells, methyl-indole treatment at 5 µM markedly suppressed p-Tyr and p-Crkl expression relative to control. The expression of p-Tyr and p-Crkl was also decreased in Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells on treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole.

Fig. 5.

Effect of methyl-indole on p-Tyr and p-Crkl expression. Analysis of p-Tyr and p-Crkl expression in pancreatic cells was made by flow cytometry. The 5 µM methyl-indole-treated or untreated cells were assessed for p-Tyr and p-Crkl expression. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. 0 µM methyl-indole

Methyl-indole targets PI3K and Akt activation

The changes in p-P13K and p-Akt expression by methyl-indole in pancreatic cells were assessed by western blotting (Fig. 6). Treatment with methyl-indole at 5 µM down-regulated in p-P13K and p-Akt expression in Capan-1 cells relative to control. The expression of p-P13K and p-Akt was also suppressed in Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells on treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole. The expression of total P13K and Akt showed no significant change in all three cell lines on treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole.

Fig. 6.

Effects of methyl-indole on P13K and Akt activation. The western blotting was carried out for assessment of changes in P13K and Akt phosphorylation in 5 µM methyl-indole-treated or untreated Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 pancreatic cells

Methyl-indole targets ZFX expression

The methyl-indole-induced changes in ZFX expression were assessed in pancreatic cells by RT-PCR and western blotting assays (Fig. 7). The expression of ZFX mRNA in Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells showed a significant reduction on treatment with 5 µM methyl-indole at 48 h. Moreover, ZFX protein expression was also down-regulated by methyl-indole at 5 µM dose in all three tested cell lines.

Fig. 7.

Effect of methyl-indole on ZFX expression. The 5 µM methyl-indole-treated or untreated cells were analyzed by a RT-PCR and b western blotting for expression of ZFX expression. *P < 0.02, **P < 0.01 vs. 0 µM methyl-indole

ZFX–GFP transfection induces resistance to methyl-indole

The cells were transfected with ZFX–GFP plasmid and then incubated with 5 µM methyl-indole (Fig. 8). In ZFX–GFP-transfected cells, ZFX expression was markedly elevated relative to empty GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 7a). The sensitivity of cells to methyl-indole was decreased by ZFX–GFP transfection relative to empty GFP transfection. The methyl-indole-induced suppression of Capan-1, Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cell viability was reversed significantly by ZFX–GFP transfection (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Effect of ZFX–GFP transfection on methyl-indole-induced reduction of cell viability. a The cells transfected with ZFX–GFP plasmid or empty GFP were analyzed for ZFX mRNA and protein expression. b Measurement of cellular viability in ZFX–GFP transfected cells after methyl-indole treatment or without treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. 0 µM methyl-indole

Discussion

The present study demonstrated anti-proliferative role of methyl-indole for prostate carcinoma cells and underlying mechanism. The increased p-Try protein level in carcinoma cells is indication of elevated activity of tyrosine kinase (Desplat et al. 2004). Another indicator as well as measure for activity of tyrosine kinase in cancer cells is the expression of p-crkl (La Rosée et al. 2008). The studies have found abnormally higher expression level of p-Tyr and p-crkl in carcinoma cells like leukemia cells (La Rosée et al. 2008; Hamilton et al. 2009). In the current study, changes in p-P13K and p-Akt levels in pancreatic cells by methyl-indole were explored. Methyl-indole down-regulated the levels of p-Tyr and p-Crkl markedly in tested pancreatic carcinoma cells. This suggested inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity in pancreatic cells by methyl-indole treatment. The survival of carcinoma cells depends on activation of P13K/AKT pathway; and therefore, this pathway is believed to be of therapeutic importance to in cancer treatment (Steelman et al. 2004; Burchert et al. 2005). In myeloid cells, targeting P13K/AKT pathway has been shown to activate apoptosis and regulate carcinoma growth (Wang et al. 2013; Meng et al. 2008). The present study assessed changes in p-P13K and p-Akt expression in methyl-indole-treated pancreatic cells. The data revealed methyl-indole mediated down-regulation of p-P13K and p-Akt expression in Capan-1 cells as well as Aspc-1 and MIApaCa-2 cells. The total P13K and Akt showed no significant change in all three cell lines on treatment with methyl-indole. Therefore, methyl-indole targeted P13K/Akt pathway activation in pancreatic cells to inhibit viability. Zinc-finger X-linked protein has major role in regulating several cellular processes in the carcinoma cells (Li et al. 2013; Fang et al. 2014). Down-regulation of ZFX deactivates PI3K/AKT pathway and consequently suppresses carcinoma cell growth (Zhang et al. 2016). The ZFX mediates proliferative potential of carcinoma cells and facilitates tumor development (Li et al. 2013; Fang et al. 2014). The current study analyzed ZFX mRNA and protein levels in pancreatic cells on treatment with methyl-indole. The expression of ZFX mRNA in all three tested cells showed a marked reduction on treatment with methyl-indole. Moreover, methyl-indole-treated cells also showed down-regulated levels of ZFX protein expression relative to control.

Conclusion

In summary, methyl-indole showed toxicity for prostate carcinoma cells and induced apoptotic changes. The tyrosine kinase activation was inhibited, P13K/AKT pathway down-regulated and ZFX level suppressed by methyl-indole in prostate cancer cells. Thus, methyl-indole has significance for treatment of prostate cancer and, therefore, may be studied further.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Burchert A, Wang Y, Cai D, Von Bubnoff N, Paschka P, Müller-Brüsselbach S, Ottmann OG, Duyster J, Hochhaus A, Neubauer A. compensatory Pi3-kinase/akt/mTor activation regulates imatinib resistance development. Leukemia. 2005;19:1774–1782. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens JL, et al. Spatial computation of intratumoral T cells correlates with survival of patients with pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15095. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehn DL, Siegel D, Zafar KS, Reigan P, Swann E, Moody CJ, Ross D. 5-Methoxy-1,2-dimethyl-3-[(4-nitrophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione, a mechanism-based inhibitor of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1, exhibits activity against human pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1702–1709. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplat V, Lagarde V, Belloc F, Chollet C, Leguay T, Pasquet JM, Praloran V, Mahon FX. Rapid detection of phosphotyrosine proteins by flow cytometric analysis in Bcr-Abl-positive cells. Cytometry A. 2004;62:35–45. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q, Fu WH, Yang J, Li X, Zhou ZS, Chen ZW, Pan JH. Knockdown of ZFX suppresses renal carcinoma cell growth and induces apoptosis. Cancer Genet. 2014;207:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A, Alhashimi F, Myssina S, Jorgensen HG, Holyoake TL. Optimization of methods for the detection of Bcr-aBl activity in Philadelphia-positive cells. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel S, Tu EY, Weisberg S, Esquilin M, Chambers SM, Liu B, Carson CT, Studer L, Reizis B, Tomishima MJ. ZFX controls the self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhne MW, Halatsch ME, Kahl GF, Weinel RJ. Frequent loss of expression of the potential tumor suppressor gene DCC in ductal pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2616–2619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosée P, Holm-Eriksen S, Konig H, Härtel N, Ernst T, Debatin J, Mueller MC, Erben P, Binckebanck A, Wunderle L, et al. Phospho-crKl monitoring for the assessment of Bcr-aBl activity in imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia or Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with nilotinib. Haematologica. 2008;93:765–769. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le DT, et al. Evaluation of ipilimumab in combination with allogeneic pancreatic tumor cells transfected with a GM-CSF gene in previously treated pancreatic cancer. J Immunother Hagerstown Md 1997. 2013;36:382–389. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31829fb7a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A, Ough M, Li L, Hinkhouse MM, Ritchie JM, Spitz DR, Cullen JJ. Treatment of pancreatic cancer cells with dicumarol induces cytotoxicity and oxidative stress. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4550–4558. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Zhu ZC, Liu YJ, Liu JW, Wang HT, Xiong ZQ, Shen X, Hu ZL, Zheng J. ZFX knockdown inhibits growth and migration of non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line H1299. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2460–2467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, et al. Low intratumoral regulatory T cells and high peritumoral CD8(+) T cells relate to long-term survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreatectomy. Cancer Immunol Immunother CII. 2016;65:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Yang C, Jin J, Zhou Y, Qian W. Homoharringtonine inhibits the aKT pathway and induces in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1954–1962. doi: 10.1080/10428190802320368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1039–1049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steelman LS, Pohnert SC, Shelton JG, Franklin RA, Bertrand FE, Mccubrey JA. JAK/STAT, Raf/MeK/erK, PI3K/akt and BcCR-ABl in cell cycle progression and leukemogenesis. Leukemia. 2004;18:189–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, You LS, Ni WM, Ma QL, Tong Y, Mao LP, Qian JJ, Jin J. β-catenin and aKT are promising targets for combination therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2013;37:1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg SP, Smith-raska MR, Esquilin JM, Zhang J, Arenzana TL, Lau CM, Churchill M, Pan H, Klinakis A, Dixon JE, et al. ZFX controls propagation and prevents differentiation of acute T-lymphoblastic and myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep. 2014;6:528–540. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winski SL, Faig M, Bianchet MA, Siegel D, Swann E, Fung K, Duncan MW, Moody CJ, Amzel LM, Ross D. Characterization of a mechanism-based inhibitor of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 by biochemical, X-ray crystallographic, and mass spectrometric approaches. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15135–15142. doi: 10.1021/bi011324i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Wei B, Wang Q, Ding Y, Deng Z, Lu X, Li Y. ZFX facilitates cell proliferation and imatinib resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2016;74:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s12013-016-0725-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Lu Y, Zheng Y, Yu X, Xia X, He X, Feng W, Xing L, Ling Z. Shrna-mediated silencing of ZFX attenuated the proliferation of breast cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2379-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Shu R, Yue M, Zhang S. Effect of over-expression of Zinc-finger protein (ZFX) on self-renewal and drug-resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:3025–3034. doi: 10.12659/MSM.897699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]