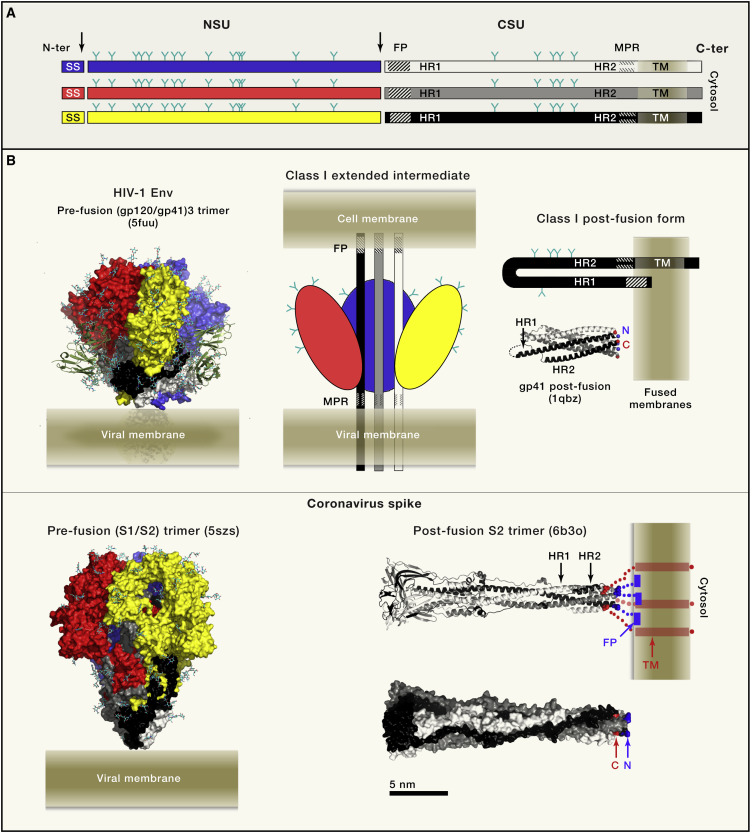

Figure 1.

Class I Viral Fusion Proteins

(A) Linear diagram illustrating the organization of the class I fusion protein polypeptide chain. A precursor glycoprotein is co-translationally translocated into the ER of the infected cell, where it is co- and post-translationally modified by glycosylation (Y symbols) and formation of disulfide bonds (not shown). An ER-resident signal peptidase generates the N terminus of the precursor upon cleavage (left vertical arrow) of the signal sequence (SS), while the precursor remains membrane-anchored through a C-terminal trans-membrane (TM) segment. The precursor folds as a trimer (represented by the three horizontal bars), which undergoes a subsequent proteolytic step (vertical arrow at the center) that generates two mature subunits NSU (N-terminal subunit, blue, red or yellow bars; the colors match the 3D diagrams in (B) and CSU (C-terminal subunit, white, gray or black bars). The two subunits remain associated in the mature trimer, which becomes metastable and primed for the irreversible conformational change that drives membrane fusion for infection of a new cell. The NSU is usually the receptor binding subunit, although in some viruses a separate protein carries this function. The CSU is the viral fusion protein, with a fusion peptide at its N-terminal end (symbolized by a dashed region) and an external membrane-proximal region (MPR) near the TM domain (symbolized by short dashes).

(B) Two representative class I fusion proteins in their prefusion conformation shown in surface representation (left panels), with NSU and CSU colored according to panel A. The glycan chains are shown as sticks with carbon atoms cyan and oxygen atoms red. The viral membrane is diagrammed to scale, with the aliphatic moiety in dark beige at the center, dingfa out as it enters the hydrophilic lipid head-group moiety. Left, top panel, structure of a fully-glycosylated, clade B native HIV Env trimer determined by cryo-EM to 4.4Å resolution (Lee et al., 2016) in the presence of the TM segment (empty arrow) and in complex with bnAb PGT151, which is displayed with the variable domains as green ribbons. The MPR segment and TM region appeared mostly disordered. The bottom left panel shows the cryo-EM structure of the NL63 α-coronavirus NL63 spike protein ectodomain, determined to 3.4Å resolution, and displaying clear density for many of the N-linked glycans (Walls et al., 2016b). The prefusion forms display the NSU subunit (S1 in coronaviruses and gp120 in HIV) making a crown (red/yellow/blue) around a spring-loaded CSU (black/gray/white; S2 in coronaviruses and gp41 in HIV). Interactions with the target cell trigger the release of the NSU crown, allowing the CSU to undergo a fusogenic conformational change going through an extended intermediate that bridges the two membranes (represented in the top-middle panel). The hairpin conformation adopted by the CSU (diagrammed at the top right) has the fusion peptide inserted into the membrane next to its TM region. A schematic fused membrane is shown to scale. Immediately below the hairpin is a ribbon representation of the postfusion CSU from SIV (gp41), forming a 6-helix bundle (Yang et al., 1999). The N and C-terminal ends of the gp41 subunit in black are marked. The two lower panels show a representative structure of the coronavirus postfusion CSU trimers displayed as ribbons (middle) and as surface representation (bottom) (Walls et al., 2017) with the N-and C-terminal ends visible in the structure of the ectodomain indicated in blue and red, respectively. A schematic on the ribbon diagram shows the expected location of the missing segments in the intact postfusion protein on membranes (not present in the structure; blue at the N-terminal end, connecting to the fusion peptide inserted superficially on the outer lipid leaflet of the fused membranes, represented as a full blue rectangle) and the C-terminal end in red, connecting to the TM helices and the cytosolic tail.