Abstract

The Impella percutaneous mechanical circulatory support device is designed to augment cardiac output and reduce left ventricular wall stress and aims to improve survival in cases of cardiogenic shock. In this meta-analysis we investigated the haemodynamic effects of the Impella device in a clinical setting. We systematically searched all articles in PubMed/Medline and Embase up to July 2019. The primary outcomes were cardiac power (CP) and cardiac power index (CPI). Survival rates and other haemodynamic data were included as secondary outcomes. For the critical appraisal, we used a modified version of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services quality assessment form. The systematic review included 12 studies with a total of 596 patients. In 258 patients the CP and/or CPI could be extracted. Our meta-analysis showed an increase of 0.39 W [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24, 0.54], (p = 0.01) and 0.22 W/m2 (95% CI: 0.18, 0.26), (p < 0.01) for the CP and CPI, respectively. The overall survival rate was 56% (95% CI: 0.50, 0.62), (p = 0.09). The quality of the studies was moderate, mostly due to the presence of confounders. Our study suggests that in patients with cardiogenic shock, Impella support seems effective in augmenting CP(I). This study merely investigates the haemodynamic effectiveness of the Impella device and does not reflect the complete clinical impact for the patient.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12471-019-01351-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Impella, Haemodynamic monitoring, Cardiogenic shock, Heart failure, Left ventricular assist device

Introduction

The Impella (Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA) is a percutaneous mechanical circulatory support (MCS) device consisting of a non-pulsatile microaxial flow pump based on the Archimedes screw principle that propels blood from the left ventricle into the ascending aorta. Aside from increasing blood flow, the Impella device aims to reduce ventricular wall stress, thereby unloading the left ventricle, reducing oxygen consumption and decreasing infarct size [1]. A series of Impella devices are available for left ventricular support. The Impella 2.5 and Impella CP can provide haemodynamic support up to 2.5 and 3.7 l/min, respectively. The strongest Impella, the Impella 5.0, can deliver up to 5 l/min of haemodynamic support. However, this includes the use of a 21 Fr pump motor, making the implantation in the acute setting more challenging [2, 3].

MCS devices have been increasingly used as a key element in the management of patients with cardiogenic shock (CS) [4]. Based on the results of the USpella Registry, which showed a significant increase of cardiac output (CO) [5], the Impella received FDA approval in 2016 for the treatment of CS. Increased flow is beneficial in CS, since low CO and reduced perfusion pressure are the bases of CS syndrome [6]. However, these two factors are intertwined, and a decreased output does not necessarily indicate a decreased perfusion pressure and vice versa. The product of these combined parameters is the cardiac power (CP), and is the strongest haemodynamic predictor of mortality in the SHOCK trial registry [7]. This finding was confirmed in a more recent study, where the cardiac power index (CPI) was found to be the best haemodynamic predictor of survival in a CS population [8].

As CP and CPI are the best predictors for survival, we focused specifically on the effects of Impella on CP(I).

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the haemodynamic effects of the Impella during CS. Survival rate was a secondary outcome.

Search strategy

Medical literature databases PubMed/Medline and Embase were searched using the following keywords: (((Impella[tiab] OR (microaxial[tiab] OR axial[tiab]) AND flow[tiab] AND (pump*[tiab] OR catheter*[tiab]) OR percutaneous left ventricular assist device*[tiab])) AND (((cardiogenic shock[tiab] OR cardiac shock[tiab] OR cardiovascular shock[tiab] OR heart shock[tiab] OR acute cardiac failure[tiab] OR acute decompensated heart failure[tiab] OR acute heart insufficiency[tiab] OR acutely decompensated heart failure[tiab] OR ADHF[tiab] OR forward heart failure[tiab] OR low cardiac output[tiab] OR low output syndrome[tiab] OR systolic dysfunction[tiab])) OR (((Shock, Cardiogenic[Mesh] OR Heart Failure[Mesh:noexp] OR Heart Failure, Systolic[Mesh])) OR “Myocardial Infarction”[Mesh]))). A methodological filter was used to limit the results to adult humans. The search was last updated on 9 July 2019.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This article is in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (see Electronic Supplementary Material for checklist, online Table 1) [9]. Studies eligible for inclusion were original articles that met the following criteria: retrospective, prospective cohort studies and randomised controlled trials in CS patients, with a reported CS. We excluded letters, case reports and studies that focused on high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). No further restrictions on publication date, status or language were imposed.

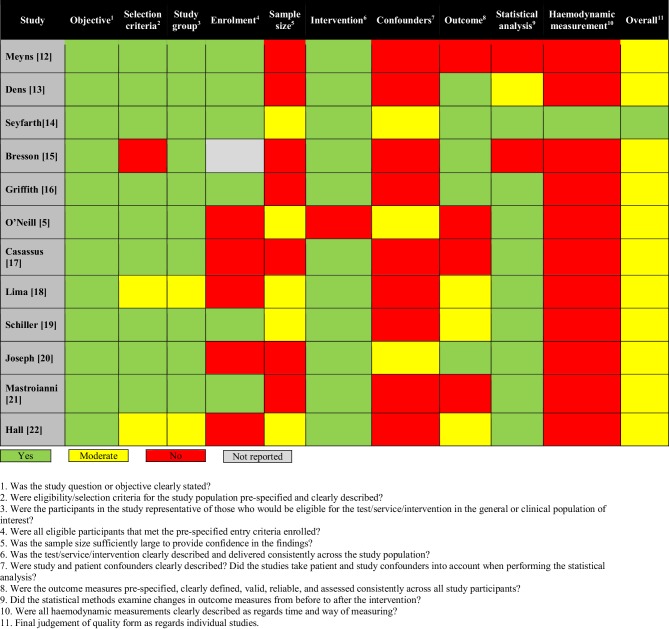

The search was then loaded into Endnote X8 and possible duplicates were deleted. The two reviewers independently reviewed all titles, abstracts and manuscripts to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Disagreement between reviewers (K.P. and D.D.) was resolved by consensus. Reference lists from eligible studies were checked to identify additional studies and citations. For the critical appraisal, we used an adapted version of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services quality assessment form (see Fig. 6; [10]).

Fig. 6.

Adapted quality assessment for individual studies according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

Both reviewers independently extracted the data from all the selected manuscripts. For haemodynamic parameters the CO, cardiac index (CI), mean arterial pressure (MAP), CP, CPI and pulmonary wedge pressure (PWP) were obtained. For non-haemodynamic parameters, type and duration of MCS, mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, gender and survival were also extracted from the individual studies.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were CP and CPI. The CP is calculated as: CO × MAP/451 [7]. The CPI was computed by substituting CO with CI in the respective formula.

Secondary outcomes included survival, type and duration of MCS, mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, gender and other haemodynamic data (CO, CI, MAP, PWP).

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using Review Manager 5.3.5 and Rstudio. Categorical variables were presented as percentages. Continuous variables were presented as range or mean ± standard deviation (SD). For continuous variables reported as median ± interquartile range, the mean and SD were estimated by using the formula as proposed by Hozo et al. [11]. Not all studies mentioned the CP or CPI directly; therefore the missing CP or CPI and accessory SD were calculated according to the appropriate formulas [11].

Heterogeneity defined as variation among the results of the individual studies was assessed with Cochrane’s Q‑statistic (pchance and I2 statistic). Random effects models were used to calculate mean pooled differences of haemodynamic data between baseline and Impella support for CP and CPI. A subgroup analysis of the Impella 2.5 and 5.0 was made. For survival rates, the overall proportion from studies reporting a single proportion was calculated. Note that since not all variables were measured in all patients and all studies, the number of patients and studies per meta-analysis is different.

Results

Study characteristics

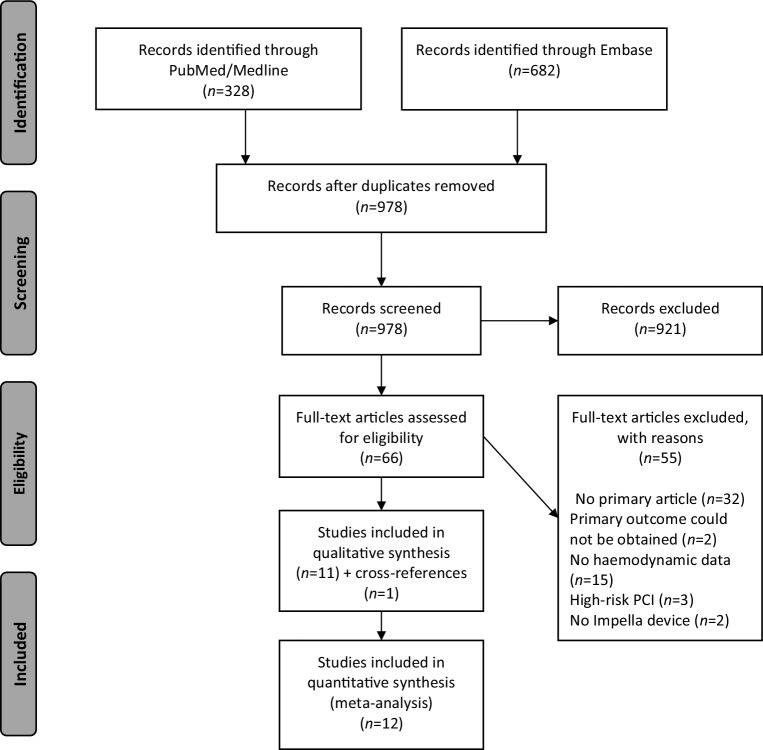

Our systematic literature search in PubMed/Medline and Embase resulted in 946 records (Fig. 1). After exclusion, 12 articles (including 1 via cross-reference) remained for qualitative and quantitative synthesis and meta-analysis [5, 12–22]. Nine of the 12 studies were observational. Two were prospective single-arm trials and one study was a randomised controlled trial. The Impella 2.5 was investigated in five studies, the Impella 5.0 in six studies and one study investigated both devices.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the included studies [9]. PCI Percutaneous coronary intervention

Patients

The systematic review included 12 studies with a total of 596 patients studied. Patient characteristics are shown in Tab. 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Year | Study type | Number of patients | Type of Impella | Indication | CS-AMI | Age (years) |

Male (%) |

MV (%) |

CPR (%) |

Support (days) | LVEF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meyns [12] | 2003 | Registry | 13 | 5.0 | CS | 6/16 | 60 ± n.a. | 69 | – | – | 4.0 ± n.a. | – |

| Dens [13] | 2006 | Prospective | 11 | 2.5 | CS-AMI | 11 | 61 ± 11 | 73 | – | – | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 29 ± 11 |

| Seyfarth [14] | 2008 | RCT | 13 | 2.5 | CS-AMI | 13 | 65 ± 10 | 62 | 92 | 85 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 27 ± n.a. |

| Bresson [15] | 2011 | Registry | 5 (9) | 5.0 | CS | 6/11 | 50 ± 14 | 83 | 100 | – | 12 ± 7.3 | – |

| Griffith [16] | 2013 | Prospective | 16 | 5.0 | CS* | 0/16 | 58 ± 9 | 81 | – | – | 3.7 ± 2.9 | 23 ± 7 |

| O’Neill [5] | 2014 | Registry | 23 (154) | 2.5 | CS-AMI | 154 | 64 ± 13 | 71 | 66 | 49 | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 26 ± 13 |

| Casassus [17] | 2015 | Registry | 9 (22) | 2.5 | CS-AMI | 22 | 58 ± 12 | 59 | 55 | 55 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 27 ± 8 |

| Lima [18] | 2016 | Registry | 21 (40) | 5.0 | ESHF | 0/40 | 55 ± 13 | 78 | 65 | – | 7 ± 5 | 12 ± 5 |

| Schiller [19] | 2016 | Registry | 66 | 2.5/5.0 | CS | 26/66 | 55 ± 2 | 65 | – | – | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 28 ± 14 |

| Joseph [20] | 2016 | Registry | 35 (180) | 2.5 | CS-AMI | 180 | 66 ± 13 | 73 | 77 | 55 | n.a. | 26 ± 12 |

| Mastroianni [21] | 2017 | Registry | 14 | 5.0 | CS* | 0/14 | 64 ± 15 | 79 | 71 | – | 8.5 ± 4.7 | – |

| Hall [22] | 2018 | Observational | 58 | 5.0 | ESHF | 0/58 | 55 ± 13 | 79 | 24 | – | 7 ± 5 | 13 ± 7 |

CS-AMI cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction; CS* cardiogenic shock post-surgery; ESHF end-stage heart failure; MV mechanical ventilation; CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; – not available

Indications for Impella implant were CS after acute myocardial infarction (CS-AMI) in 380 (64%), end-stage heart failure in 96 (16%) and post-cardiac surgery in 30 patients (5%). The remaining 88 (15%) patients had Impella implanted for various causes of CS.

During hospital admission, 55–100% of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 49–85% had cardiopulmonary resuscitation prior to Impella implantation. In all studies, patients were pharmacologically supported by inotropic and/or vasopressor agents and in 9 of the 12 studies (74% of all patients) PCI was conducted. The mean duration of support with the Impella was 0.9–12 days.

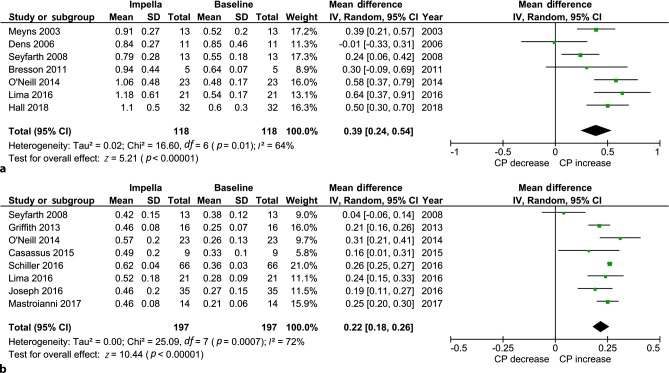

Meta-analysis

CO and/or CI were reported in 258 (43%) patients (see Tab. 1). Using a random effect model, use of the Impella led to an increase in CP of 0.39 W [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24, 0.54], (p = 0.01) and CPI 0.22 W/m2 (95% CI: 0.18, 0.26), (p < 0.01); see Tab. 2 and Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Individual study results of haemodynamic support and survival

| Study | Type of device |

CP (W) |

CPI (W/m2) |

CO (l/min) |

CI (l/min/m2) |

MAP (mm Hg) |

Survival (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Support | Baseline | Support | Baseline | Support | Baseline | Support | Baseline | Support | |||

| Meyns [12] | 5.0 | 0.52 ± 0.20 | 0.91 ± 0.27 | – | – | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | – | – | 57 ± 13 | 75 ± 13 | 46 |

| Dens [13] | 2.5 | 0.85 ± 0.46 | 0.84 ± 0.27 | – | – | 4.4 ± 1.9 | 4.8 ± 1.2 | – | – | 87 ± 25 | 79 ± 16 | 55 |

| Seyfarth [14] | 2.5 | 0.55 ± 0.18 | 0.79 ± 0.28 | 0.30 ± 0.12 | 0.42 ± 0.15 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 78 ± 16 | 87 ± 8 | 54 |

| Bresson [15] | 5.0 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.44 | – | – | 4 ± 0.55 | 5.9 ± 2.7 | – | – | – | – | 44 |

| Griffith [16] | 5.0 | – | – | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.08 | – | – | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 71 ± 13 | 83 ± 7.5 | 75 |

| O’Neill [5] | 2.5 | 0.48 ± 0.17 | 1.06 ± 0.48 | 0.26 ± 0.13 | 0.57 ± 0.20 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 63 ± 19 | 94 ± 23 | 51 |

| Casassus [17] | 2.5 | – | – | 0.33 ± 0.10 | 0.49 ± 0.20 | – | – | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 67 ± 15 | 82 ± 13 | 59 |

| Lima [18] | 5.0 | 0.54 ± 0.17 | 1.18 ± 0.61 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | 0.52 ± 0.18 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 71 ± 11 | 82 ± 20 | 68 |

| Schiller [19] | 2.5/5.0 | 0.66 ± 0.2 | – | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | – | – | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 73 ± 2 | 73 ± 2 | 58 |

| Joseph [20] | 2.5 | – | – | 0.27 ± 0.15 | 0.46 ± 0.20 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | – | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 60 ± 28 | 87 ± 27 | 44 |

| Mastroianni [21] | 5.0 | – | – | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.08 | – | – | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 60 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | 57 |

| Hall [22] | 5.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | – | – | 3.7 ± 1.9 | – | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 70 ± 11 | – | 67 |

Variables are presented as mean ± SD

CO cardiac output; CI cardiac index; MAP mean arterial pressure; CP cardiac power; CPI cardiac power index; W Watt; – not available

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of a cardiac power (CP) and b cardiac power index

Use of the Impella 2.5 showed a mean pooled increase in CP and CPI of 0.29 W (95% CI: −0.02, 0.59), (p = 0.07), +48% and 0.18 W/m2 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.29), (p < 0.01), +58%, respectively. Use of the Impella 5.0 led to a mean pooled increase in CP and CPI of 0.46 W (95% CI: 0.35, 0.58), (p < 0.01), +82% and 0.27 W/m2 (95% CI: 0.17, 0.38), (p < 0.01), +102%. See Electronic Supplementary Material, online Figs. 1 and 2.

The majority of the patients received an Impella for CS after an AMI, which comprised 63% of the total study population. When analysing the AMI-CS specifically, the CPI increase was similar to that of the whole group (n = 258). See Electronic Supplementary Material, online Fig. 3.

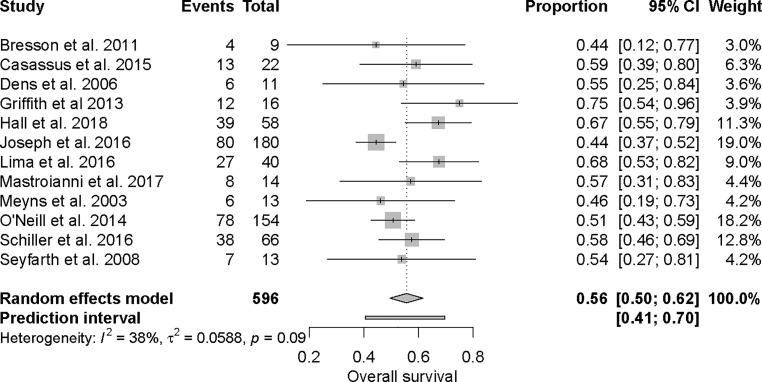

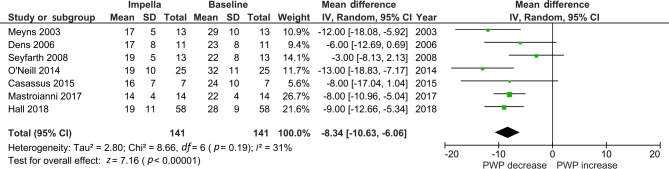

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of survival

The mean survival rate was 56% (95% CI: 0.50, 0.62), (p = 0.09), see Fig. 3. MAP increased with a pooled mean difference of 13 mm Hg (95% CI: 3.74, 22.98), (p < 0.01). PWP decreased when the Impella was used with a mean pooled difference of −8.30 mm Hg (95% CI: −10.63, −6.06), (p < 0.01). See Tab. 2, Figs. 4 and 5 and Electronic Supplementary Material.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of mean arterial pressure (MAP)

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of pulmonary wedge pressure (PWP)

Critical appraisal

One study was considered of sufficiently good quality to show that Impella support results in increased CP and CPI [14]. Overall studies were considered to be of moderate quality, mostly due to lack of description of confounders and data acquisition protocol. On the other hand, all studies were comparable in terms of outcomes, study design, study population and type of support, which allowed us to conduct a meta-analysis (see Fig. 6).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that has focused on the increase in CP and CPI during Impella support. This meta-analysis, including 258 patients from 12 studies, showed that the use of the Impella device significantly increases the CP by 0.39 W (+67%) and CPI by 0.22 W/m2 (+76%). When comparing the different Impella devices, the Impella 2.5 in general achieves a lower performance relative to the Impella 5.0 in both CP (+48% vs +82%) and CPI (+58% vs +102%).

The observed increase in CP(I) during Impella support, which has been shown to be a strong haemodynamic predictor of survival in CS [7, 8], should theoretically lead to a reduction in mortality. Extrapolating from the survival graph of Fincke et al., the increase of CP from 0.5 W to 0.9 W should decrease mortality from approximately 50% to 20% [7]. The overall percentage survival in our meta-analysis, 56%, is in line with two small randomised controlled trials [14, 23] and a propensity-matched analysis [24], which all compared the Impella CP to passive unloading with the intra-aortic balloon pump. This indicates that the relationship between (mechanical) haemodynamic improvement and survival is less evident than suggested.

In our study we focused mainly on CS after AMI (64% in our analysis). However, CS has a broad scope of aetiology. In some very specific indications, such as a biopsy-proven myocarditis, there is growing evidence of improved survival with Impella support [25]. In other indications for Impella support, such as the post-cardiotomy population (5% in our study), evidence is still limited and in need of further research. However, small registries show survival rates comparable with those of more invasive assist devices, such as surgically implantable ventricular assist devices [26]. Therefore, patient selection in terms of cause and reversibility of cause is an important determinant of survival in CS.

Within the CS-AMI group, patient selection might be an explanation for the lack of a clear survival benefit with improved haemodynamics. Patients with a relatively preserved cardiac function seem to have the best chance of survival and show a better haemodynamic improvement [27]. In patients who have no cardiac reserve, the intrinsic CP is unchanged and thus remains the Achilles’ heel of survival. Only when the affected myocardium is able to recover can the intrinsic CP increase and thereby improve outcome.

To achieve recovery of the myocardium Impella provides unloading, represented by a significant decrease of the PWP by 8 mm Hg in our meta-analysis. This clearly distinguishes mechanical support with the Impella device from medical therapy (inotropic or vasoactive agents), which increases the workload of the heart in order to improve the CPI [28]. Unloading of the left ventricle leads to reduced oxygen consumption and should thereby reduce infarct size in patients with CS-AMI. Animal studies have shown that unloading does reduce infarct size [1, 29], especially when support is started at an early stage. However, the clinical trial which investigated if unloading with Impella support would reduce the infarct size (MINI-AMI, Minimizing Infarct Size with Impella 2.5 Following PCI for Acute Myocardial Infarction, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01319760) was terminated due to a ‘change in company priority’. This raises questions as to whether the study was able to show positive results.

In terms of the timing of support, several studies suggest that early implantation of a mechanical assist device would improve survival [30–32]. Recent extensive animal studies showed that mechanical unloading of the left ventricle before coronary reperfusion limits the expression of proteolytic enzymes. This resulted in less cell decay, reduced infarction size and better haemodynamic performance [33]. A recent clinical trial also showed promising results when the Impella support was initiated before emergency PCI [34]. This is in contrast to our meta-analysis, in which support was given after almost 3 days after the onset of CS. The late initiation of support might preclude the potential benefit to survival rates. On the other hand, real-world data are refractory. In the 12-year experience of the Amsterdam Medical Centre there was no significant improvement of survival when support was initiated before PCI [35].

Clinical and future perspectives

In the critical setting of CS, the Impella device improves the haemodynamic state and relieves congestion. However, in order to significantly improve outcomes, more research is needed. Patient selection and timing of Impella support may well be the crucial denominator that decides its effectiveness. To further optimise patient selection and to overcome heterogenic outcomes in future studies on MCS, we suggest a standard data set of core outcomes and measurements.

Limitations

Eight of the 12 included studies were registries, which in general have a heterogeneous patient population, treatment and outcome. Additionally, 3 out of 12 studies are from the cVAD (catheter-based ventricular assist devices) registry, owned by Abiomed. Possible overlap cannot be excluded. When taking these studies out of the calculation, the overall results remain the same.

The key hindrance to providing an in-depth meta-regression analysis at the study level is the great disparity in the available data reported. Possible confounding factors are not always reported, including the use of vasoactive medication, clinical patient characteristics and the timing and completeness of measurements. Although the overall quality of the studies was considered moderate, all studies showed a uniform increase in CP(I). This was reflected by an acceptable heterogeneity score for the overall study group.

Furthermore, although the intrinsic CP(I) may be a strong predictor in CS-AMI, this relationship might be less strong for the CP(I) added by MCS. This distinction is crucial for adequate interpretation of our results. In addition, this meta-analysis focuses on the haemodynamic efficacy in the clinical setting, and merely reflects whether the pump is effective in increasing output. Procedure- and device-related complications (stroke, access bleeding, infection) are not included in this study, hampering the true reflection of clinical benefit for the patient.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis shows that short-term MCS with the Impella device is effective in increasing CP and CPI. Despite successfully increased CP with Impella support, the mortality seems to be in line with the survival rate without Impella use.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplemantery Fig. 1: Forest plot comparison of change in cardiac power (CP) between Impella 5.0 and 2.5.

Supplementary Fig. 2: Forest plot comparison of change in cardiac power index (CPI) between Impella 5.0 and impella 2.5.

Supplemetary Fig. 3: Forest plot of the cardiac power (index) (CP(I)) between cardiogenic shock patients based myocardial infarction (AMI-CS) and other cardiogenic shock patients (non AMI-CS).

Supplementary Table 1: PRISMA checklist used for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

D.I.M. van Dort is a shareholder of and consultant to CardiacBooster B.V. and K.R.A.H. Peij Peij is an employee of CardiacBooster B.V. O.C. Manintveld, S.E. Hoeks, W.J. Morshuis, N. van Royen, T. Ten Cate and G.S.C. Geuzebroek declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

D.I.M. van Dort and K.R.A.H. Peij contributed equally to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wei X, Li T, Hagen B, et al. Short-term mechanical unloading with left ventricular assist devices after acute myocardial infarction conserves calcium cycling and improves heart function. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.12.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burzotta F, Trani C, Doshi SN, et al. Impella ventricular support in clinical practice: collaborative viewpoint from a European expert user group. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rihal CS, Naidu SS, Givertz MM, et al. SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS clinical expert consensus statement on the use of percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices in cardiovascular care (endorsed by the American Heart Association, the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencion; affirmation of value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d’intervention) J Card Fail. 2015;2015(21):499–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stretch R, Sauer CM, Yuh DD, Bonde P. National trends in the utilization of short-term mechanical circulatory support: incidence, outcomes, and cost analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1407–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neill WW, Schreiber T, Wohns DH, et al. The current use of Impella 2.5 in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results from the USpella Registry. J Interv Cardiol. 2014;27:1–11. doi: 10.1111/joic.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: expanding the paradigm. Circulation. 2003;107:2998–3002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000075927.67673.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM, et al. Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sionis A, Rivas-Lasarte M, Mebazaa A, et al. Current use and impact on 30-day mortality of pulmonary artery catheter in cardiogenic shock patients: results from the CardShock study. J Intensive Care Med. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0885066619828959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group [available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools]. Accessed 12 January 2018.

- 11.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyns B, Dens J, Sergeant P, et al. Initial experiences with the Impella device in patients with cardiogenic shock—Impella support for cardiogenic shock. Thorac cardiovasc Surg. 2003;51:312–317. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dens J, Meyns B, Hilgers R-D, et al. First experience with the Impella Recover® LP 2.5 micro axial pump in patients with cardiogenic shock or undergoing high-risk revascularisation. EuroIntervention. 2006;2:84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I, et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1584–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bresson D, Sibellas F, Farhat F, et al. Preliminary experience with Impella Recover ® LP5.0 in nine patients with cardiogenic shock: a new circulatory support system in the intensive cardiac care unit. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;104:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith BP, Anderson MB, Samuels LE, et al. The RECOVER I: a multicenter prospective study of Impella 5.0/LD for postcardiotomy circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiov Sur. 2013;145:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casassus F, Corre J, Leroux L, et al. The use of Impella 2.5 in severe refractory cardiogenic shock complicating an acute myocardial infarction. J Interv Cardiol. 2015;28:41–50. doi: 10.1111/joic.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lima B, Kale P, Gonzalez-Stawinski GV, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the Impella 5.0 as a bridge to cardiac transplantation or durable left ventricular assist device. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiller P, Vikholm P, The Impella HL. R) Recover mechanical assist device in acute cardiogenic shock: a single-centre experience of 66 patients. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2016;22:452–458. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph SM, Brisco MA, Colvin M, et al. Women with cardiogenic shock derive greater benefit from early mechanical circulatory support: an update from the cVAD registry. J Interv Cardiol. 2016;29:248–256. doi: 10.1111/joic.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mastroianni C, Bouabdallaoui N, Leprince P, Lebreton G. Short-term mechanical circulatory support with the Impella 5.0 device for cardiogenic shock at La Pitie-Salpetriere. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;6:87–92. doi: 10.1177/2048872616633877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall SA, Uriel N, Carey SA, et al. Use of a percutaneous temporary circulatory support device as a bridge to decision during acute decompensation of advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouweneel DM, Eriksen E, Sjauw KD, et al. Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support versus intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrage B, Ibrahim K, Loehn T, et al. Impella support for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Circulation. 2019;139:1249–1258. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annamalai SK, Esposito ML, Jorde L, et al. The Impella microaxial flow catheter is safe and effective for treatment of myocarditis complicated by cardiogenic shock: an analysis from the global cVAD registry. J Card Fail. 2018;24:706–710. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engstrom AE, Granfeldt H, Seybold-Epting W, et al. Mechanical circulatory support with the Impella 5.0 device for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: a three-center experience. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2013;61:539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegenthaler MP, Brehm K, Strecker T, et al. The Impella Recover microaxial left ventricular assist device reduces mortality for postcardiotomy failure: a three-center experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:812–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nativi-Nicolau J, Selzman CH, Fang JC, Stehlik J. Pharmacologic therapies for acute cardiogenic shock. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2014;29:250–257. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshitake I, Hata M, Sezai A, et al. The effect of combined treatment with Impella((R)) and landiolol in a swine model of acute myocardial infarction. J Artif Organs. 2012;15:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s10047-012-0640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basir MB, Schreiber TL, Grines CL, et al. Effect of early initiation of mechanical circulatory support on survival in cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazkani M, Murarka S, Kobayashi A, et al. A retrospective analysis of Impella use in all-comers: 1-year outcomes. J Interv Cardiol. 2017;30:577–583. doi: 10.1111/joic.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meraj PM, Editorial DR. Stop thinking and start acting: Early Impella placement associated with improved outcomes, again! J Interv Cardiol. 2017;30:584–585. doi: 10.1111/joic.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esposito ML, Zhang Y, Qiao X, et al. Left ventricular unloading before reperfusion promotes functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:501–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basir MB, Schreiber T, Dixon S, et al. Feasibility of early mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: the Detroit cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:454–461. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouweneel DM, de Brabander J, Karami M, et al. Real-life use of left ventricular circulatory support with Impella in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction: 12 years AMC experience. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:338–349. doi: 10.1177/2048872618805486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemantery Fig. 1: Forest plot comparison of change in cardiac power (CP) between Impella 5.0 and 2.5.

Supplementary Fig. 2: Forest plot comparison of change in cardiac power index (CPI) between Impella 5.0 and impella 2.5.

Supplemetary Fig. 3: Forest plot of the cardiac power (index) (CP(I)) between cardiogenic shock patients based myocardial infarction (AMI-CS) and other cardiogenic shock patients (non AMI-CS).

Supplementary Table 1: PRISMA checklist used for this systematic review and meta-analysis.