Abstract

This paper investigates whether the inclusion of social scientists in the UK policy network that responded to the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone (2013–16) was a transformational moment in the use of interdisciplinary research. In contrast to the existing literature, that relies heavily on qualitative accounts of the epidemic and ethnography, this study tests the dynamics of the connections between critical actors with quantitative network analysis. This novel approach explores how individuals are embedded in social relationships and how this may affect the production and use of evidence. The meso-level analysis, conducted between March and June 2019, is based on the traces of individuals' engagement found in secondary sources. Source material includes policy and strategy documents, committee papers, meeting minutes and personal correspondence. Social network analysis software, UCINet, was used to analyse the data and Netdraw for the visualisation of the network. Far from being one cohesive community of experts and government officials, the network of 134 people was weakly held together by a handful of super-connectors. Social scientists’ poor connections to the government embedded biomedical community may explain why they were most successful when they framed their expertise in terms of widely accepted concepts. The whole network was geographically and racially almost entirely isolated from those affected by or directly responding to the crisis in West Africa. Nonetheless, the case was made for interdisciplinarity and the value of social science in emergency preparedness and response. The challenge now is moving from the rhetoric to action on complex infectious disease outbreaks in ways that value all perspectives equally.

Keywords: Sierra Leone, Ebola, Social network analysis, Virus, Zoonosis, Health emergency, Epistemic community, Policy network

Highlights

-

•

Unique focus on empirical social network data that explore how relationships affect evidence use.

-

•

Disputes claims that the Ebola research-policy network was interdisciplinary and transformative.

-

•

Social science sub-community weakly connected into core policy network reducing their influence.

-

•

Anthropologists were most successful when they framed their expertise in terms of widely accepted concepts.

-

•

Africans almost entirely absent from network which was dominated by UK biomedical scientists.

1. Introduction

Global health governance is increasingly focused on epidemic and pandemic health emergencies that require an interdisciplinary approach to accessing scientific knowledge to guide preparedness and crisis response. Of acute concern is Zoonotic disease, that can spread from animals to humans and easily cross borders. The “grave situation” of the Chinese Coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak seems to have justified these fears and is currently the focus of an international mobilisation of scientific and state resources (Wood, 2020). Covid-19 started in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province and has been declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The interactions currently taking place, nationally and internationally between evidence, policy and politics, are complex and relate to theories around the role of the researcher as broker or advocate and the form and function of research policy networks (Pielk, 2007) and (Ward et al., 2011) and (Georgalakis and Rose, 2019). In this paper I seek to explore these areas further through the lens of the UK's response to Ebola in West Africa. This policy context has been selected in relation to the division of the affected countries between key donors. The British Government assumed responsibility for Sierra Leone and sought guidance from health officials, academics, humanitarian agencies and clinicians.

The Ebola epidemic that struck West Africa in 2013 has been described as a “transformative moment for global health” (Kennedy and Nisbett, 2015, p.2), particularly in relation to the creation of a transdisciplinary response that was meant to take into account cultural practices and the needs of communities. The mobilisation of anthropological perspectives towards enhancing the humanitarian intervention was celebrated as an example of research impact by the UK's Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Department for International Development (DFID) (ESRC, 2016). An eminent group of social scientists called for future global emergency health interventions to learn from this critical moment of interdisciplinary cooperation and mutual understanding (S. A. Abramowitz et al., 2015). However, there has been much criticism of this narrative, ranging from the serious doubts of some anthropologists themselves about their impact (Martineau et al., 2017), to denouncements of largely European and North American anthropologists' legitimacy and the utility of their advice (Benton, 2017).

There are two questions I hope to address through a critical commentary on the events that unfolded and with social network analysis of the UK based research and policy network that emerged: i) How transformational was the UK policy response to Ebola in relation to changes in evidence use patterns and behaviours? ii) How does the form and function of the UK policy network relate to epistemic community theory? The first question will explore the degree to which social scientists and specifically anthropologists and medical anthropologists, were incorporated into the UK policy network. The second question seeks to locate the dynamics of this network in the literature on network theory and the role of epistemic communities in influencing policy during emergencies.

The paper does not attempt to evidence the impact of anthropology in the field or take sides in hotly debated issues such as support for home care. Instead, it looks at how individuals are embedded in social relationships and how this may affect the production and use of evidence (Victor et al., 2017). The emerging field of network analysis around the generation and uptake of evidence in policy, recommends this critical realist constructivist methodology. It utilises interactive theories of evidence use, the study of whole networks and the analysis of the connections between individuals in policy and research communities (Nightingale and Cromby, 2002; Oliver and Faul, 2018).

Although Ebola related academic networks have been mapped, this methodological approach has never previously been applied to the policy networks that coalesced around the international response. Hagel et al. show how research on the Ebola virus rapidly increased during the crisis in West Africa and identified a network of institutions affiliated through co-authorship. Unfortunately, their data tell us very little about the type of research being published and how it was connected into policy processes (Hagel et al., 2017). In contrast, this paper seeks to inform the ongoing movements promoting interdisciplinarity as key to addressing global health challenges. Zoonotic disease has been the subject of particular concerns around the, “connections and disconnections between social, political and ecological worlds” (Bardosh, 2016, P. 232). With the outbreak of Covid-19 in China at the end of 2019, its rapid spread overseas and predictions of more frequent and more deadly pandemics and epidemics in the future, the importance of breaking down barriers between policy actors, humanitarians, social scientists, doctors and medical scientists can only increase with time.

1.1. The policy areas and the evidence

Before we look at detailed accounts of events relating to the UK policy network, first we must consider what the key policy issues were relating to an anthropological response versus a purely clinical one. Anthropological literature exists, from previous outbreaks, documenting the cultural practices that affected the spread of Ebola (Hewlett and Hewlett, 2007). The main concerns relate to how local practices may accelerate the spread of the virus and the need to address these in order to lower infection rates. Ebola is highly contagious, particularly from contamination by bodily fluids. In West Africa, many local customs exist around burial practices that clinicians believe heighten the risk to communities. Common characteristics of these are, the washing of bodies by family members, passing clothing belonging to the deceased to family and the touching of the body (Richards, 2016). Another concern, as the crisis unfolded, was people attempting to provide home care to victims of the virus. The clinical response was to create isolation units or Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) in which to assess and treat suspected cases (West & von Saint André-von Arnim, 2014). Community based care centres were championed by the UK Government but their deployment came late and opinion was divided around their effectiveness. Clinicians regarded ETUs as an essential part of the response and wanted to educate people to discourage them from engaging in what they regarded as deeply unsafe practices, including home care (Walsh and Johnson, 2018) and (MSF, 2015).

Anthropologists with expertise in the region focused instead on engaging communities more constructively, managing stigma and understanding local behaviours and customs (Fairhead, 2014), (Richards, 2014b) and (Berghs, 2014). Anthropologist, Paul Richards, argues that agencies' and clinicians’ lack of understanding of local customs worsened the crisis (Richards, 2016) and that far from being ignorant and needing rescuing from themselves, communities had coping strategies of their own. His studies from Sierra Leone and Liberia relate how some villages isolated themselves, created their own burial teams and successfully protected those who came in contact with suspected cases with makeshift protective garments (Richards, 2014a). Anthropologists working in West Africa during the epidemic prioritised studies of social mobilisation and community engagement and worked with communities directly on Ebola transmission. Sharon Abramowitz, in her review of the anthropological response across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, provides examples from the field work of Chiekh Niang (Fleck, 2015), Sylvain Faye, Juliene Anoko, Almudena Mari Saez, Fernanda Falero, Patricia Omidian, several Medicine Sans Frontiers (MSF) anthropologists and others (S. Abramowitz, 2017). However, Abramowitz argues that learning generated by these ethnographic studies was largely ignored by the mainstream response.

However, not everyone has welcomed the intervention of the international anthropological community. Some critics have argued that social scientists in mostly European and North American universities were poorly suited to providing sound advice given their lack of familiarity with field-based operations. Adia Benton suggests that predominantly white northern anthropologists have an “inflated sense of importance” that led them to exaggerate the relevance of their research. This in turn helped reinforce concepts of “superior northern knowledge” (Benton, 2017, p. 520). This racial optic seems to contradict the portrayal of plucky anthropologists being the victims of knowledge hierarchies that favour other knowledges over their own.

1.2. How an epistemic community emerged

Our focus here, on the mobilisation of knowledge from an international community of experts, recommends that we consider how this can be understood in relation to group dynamics as well as individual relationships. Particularly relevant is Peter Haas’ theory of epistemic communities. Haas helped define epistemic communities and how they differ from other policy communities, such as interest groups and advocacy coalitions (Haas, 1992). They share common principles and analytical and normative beliefs (causal beliefs). They have an authoritative claim to policy relevant expertise in a particular domain and Haas claims that policy actors will routinely place them above other interest groups in their level of expertise. He believes that epistemic communities and smaller more temporary collaborations within them, can influence policy. He observes that in times of crisis and acute uncertainty, policy actors often turn to them for advice.

The emergence of an epistemic community focused on the UK policy response was framed by the division of the affected countries between key donors along historic colonial lines. Namely, the UK was to lead in Sierra Leone, the United States in Liberia and the French in Guinea. This seems to have focused social scientists in the UK on engaging effectively with a government and wider scientific community who seemed to want to draw on their expertise. This was a relatively close-knit community of scholars who already worked together, co-published and cited each other's work and in many cases worked in the same academic institutions. Crucially, their ranks were swelled by a small number of epidemiologists and medical anthropologists who shared their concerns.

From the time MSF first warned the international community of an unprecedented outbreak of Ebola in Guinea at the end of March 2014, it was six months before an identifiable and organised movement of social scientists emerged (MSF, 2015). Things began to happen quickly when the WHO announced in early September of that year that conventional biomedical responses to the outbreak were failing (WHO, 2014a). This acted like a siren call to social scientists incensed by the reported treatment of local communities and the way in which a narrative had emerged blaming local customs and ignorance for the rapid spread of the virus. British anthropologist, James Fairhead, hastily organised a special panel on Ebola at the African Studies Association (ASA) Annual Conference, that was taking place at the University of Sussex (UoS) on the September 10, 2014. Amongst the panellists were: Anthropologist Melissa Leach, Director of the Institute of Development Studies (IDS); Audrey Gazepo, University of Ghana, Medical anthropologist Melissa Parker from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM); Anthropologist and public health specialist, Anne Kelly from Kings College London and Stefan Elbe, UoS. Informally, after the conference, this group discussed the idea of an online repository or platform for the supply of regionally relevant social science (F. Martineau et al., 2017). This would later become the Ebola Response Anthropology Platform (ERAP). In the days and weeks that followed it was the personal and professional connections of these individuals that shaped the network engaging with the UK's intervention.

1.3. Anthropologists get a seat at the table

Just two days after the emergency panel at the ASA, Jeremy Farrar, Director of the Wellcome Trust, convened a meeting of around 30 public health specialists and researchers, including Leach, on the UK's response to the epidemic. Discussions took place on the funding and organisation of the anthropological response. The Government was already drawing on the expertise and capacity of Public Health England (PHE), the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the Department of Health (DoH), to drive its response but social scientists had no seat at the table. The Government's Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Sally Davies called a meeting of the Ebola Scientific Assessment and Response Group (ESARG), on the 19th September, focused on issues which included community transmission of Ebola. Leach's inclusion as the sole anthropologist was largely thanks to Farrar and Chris Whitty, DFID's Chief Scientific Advisor (M Leach, 2014). There was already broad acceptance of the need for the response to focus on community engagement and the WHO had been issuing guidance on how to engage and what kind of messaging to use for those living in the worst affected areas (WHO, 2014c). In their account of these events three of the central actors from the UK's anthropological community describe how momentum gathered quickly and that: “it felt as if we were pushing at an open door” (F. Martineau et al., 2017, 481).

By the following month, the UK's Coalition Government was embracing its role as the leading bilateral donor in Sierra Leone and wanted to raise awareness and funds from other governments and foundations. A high level conference: Defeating Ebola in Sierra Leone, had been quickly organised, in partnership with the Sierra Leone Government, at which an international call for assistance was issued (DFID, 2014). It was shortly after this that the CMO, at the behest of the Government's Cabinet Office Briefing Room (COBRA), formed the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies on Ebola (SAGE). By its first meeting on the October 16, 2014, British troops were on the ground along with volunteers from the UK National Health Service (NHS) (STC, 2016). Leach was pulled into this group along with most of the members of ESARG that had met the previous month. It was decided in this initial meeting to set up a social science sub-group including Whitty, Leach and the entire steering group of the newly established ERAP (SAGE, 2014a). This included not just British-based anthropologists but also Paul Richards and Esther Mokuwa from Njala University, Sierra Leone. From this point anthropologists appeared plugged into the Government's architecture for guiding their response.

1.4. The supply of social science knowledge begins

There were several modes for the interaction between social scientists and policy actors that focused on the UK led response. Firstly, there were the formal meetings of committees or other bodies that were set up to directly advise the UK Government in London. Secondly, there were the multitude of ad-hoc interactions, conversations, meetings and briefings, some of which were supported with written reports. Then, there was the distribution of briefings, reports and previously published works by ERAP which included use of the pre-existing Health, Education Advice and Resource Team (HEART) platform, which already provided bespoke services to DFID in the form of a helpdesk (HEART, 2019). ERAP was up and running by the 14th October and during the crisis the platform published around 70 open access reports which were accessed by over 16,000 users (ERAP, 2016). There were also a series of webinars and workshops and an online course (LSHTM, 2015).

According to IDS and LSHTM's application to the ESRC's Celebrating Impact Awards (M. Leach et al., 2016), the policy actors that participated in these interactions included: UK Government officials in DFID's London Head Quarters and its Sierra Leone Country Office, in the MOD and the Government's Office for Science (Go-Science). Closest of all to the Prime Minister and the Cabinet Office was SAGE. They also communicated with International non-governmental organisations (INGOs) like Help Aged International and Christian Aid who requested briefings or meetings. ERAP members advised the WHO via three core committees, as well as The United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER) and The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (UNFAO). By the end of the crisis members of ERAP had given written and oral evidence to three separate UK Parliamentary inquiries. These interactions were not entirely limited to policy audiences. ERAP members also contributed to the design of training sessions and a handbook on psychosocial impact of Ebola delivered to all the clinical volunteers from the NHS prior to their deployment from December 2014 onwards (redrUK, 2014).

The way in which anthropologists engaged in policy and practice seemed to reflect an underlying assumption that they would work remotely to the response and engage primarily with the UK Government, multilaterals and INGOs. A strength of this approach, apart from the obvious personal safety and logistical implications, was that anthropologists enjoyed a proximity to key actors in London. Face to face meetings could be held and committees joined in person (F. Martineau et al., 2017). A good example of a close working relationship that required a personal interaction were the links built with two policy analysts working in the MOD. Not even DFID staff had made this connection and it was thanks to a member of the ERAP steering committee that one of these officials was able to join the SAGE social science sub-committee and provide a valuable connection back into the Ministry (Martineau et al., 2017).

With proximity to the UK Government in London came distance from the policy professionals and humanitarians in Sierra Leone. Just 3% of ERAP's initial funding was focused on field work. Although, this later went up and comparative analysis on resistance in Guinea and Sierra Leone and between Ebola and Lassa Fever was undertaken (Wilkinson and Fairhead, 2017), as well as a review of the Disaster Emergency Committee (DEC) crisis appeal response (Oosterhoff, 2015). There was also an evaluation of the Community Care Centres and additional funding from DFID supported village-level fieldwork by ERAP researchers from Njala University, leading to advice to social mobilisation teams. Nonetheless, the network's priority was on giving advice to donors and multilaterals, albeit at a great distance from the action. This type of intervention has not escaped accusations of “armchair anthropology” (Delpla and Fassin, 2012) in (S. Abramowitz, 2017, p. 430).

1.5. Measuring interdisciplinarity with social network analysis

Rather than relying solely on this qualitative account, drawn largely from those directly involved in these events, Social Network Analysis (SNA) produces empirical data for exploring the connections between individuals and within groups (Crossley and Edwards, 2016). It is a quantitative approach rooted in graph theory and covers a range of methods which are frequently combined with qualitative methods (S. P. Borgatti et al., 2018). In this case, the network comprises of nodes who are the individuals identified as being directly involved in some of the key events just described. A second set of nodes are the events or interactions themselves. Content analysis of secondary sources linked to these events provides an unobtrusive method for identifying in some detail the actors who will have left traces of their involvement. SNA allows us to establish these actors’ ties to common nodes (they were part of the same committee or event or contributed to the same reports.) Furthermore, we can assign non-network related attributes to each of our nodes such as gender, location, role and organisation affiliation type. Not only does this approach provide a quantitative assessment of who was involved and through which channels but the mathematical foundations of SNA allow for whole network analysis of cohesion across certain groups. You may calculate levels of homophily (the tendency of individuals to associate with similar others) between genders, disciplines and organisational type and identify sub-networks and the super-connectors that bridge them (S. P. Borgatti et al., 2018).

1.6. Research method and sampling

The descriptive and statistical examination of graphs provides a means with which to test a hypothesis and associated network theory that is concerned with the entirety of the social relations in a network and how these affect the behaviour of individuals within them (Stovel and Shaw, 2012) and (Ward et al., 2011). The quantitative analysis of secondary sources was conducted between March and June 2019, utilising content analysis of artefacts which included reports, committee papers, public statements, policy documentation and correspondence. SNA software, UCINet, was used to analyse nodes and ties and Netdraw for the visualisation of the network (S. Borgatti et al., 2002) and (S. Borgatti and Everet, 2002). The source material is limited to artefacts relating to the UK Government's response to the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone from March 2014 until March 2016. Eight interactions prominent in the commentary have been selected. The criteria for selecting specific interactions was: i) Availability of archival data; ii) The apparent prominence or influence of these groups on the UK's response to the crisis, iii) The remit of these groups to focus on the social response, as opposed to the purely clinical one.

Tracing the events and policy moments which reveal how individual social scientists engaged with the Ebola crisis from mid-2014 requires one to look well beyond academic literature. Whilst some of this material is openly available, a degree of insider knowledge is required to identify who the key actors were and the modes of their engagement. This is partly a reflection of a sociological approach to policy research that treats networks, only partially visible in the public domain, as a social phenomenon (Gaventa, 2006).

1.7. Limitations, reliability and validity

The calculation of network homogeneity (how interconnected the network is), the identification of cliques or sub-networks and the centrality of particular nodes, can be mathematically stable measures of the function of the network. However, the reliability of this study mainly resides on its validity. The assignment of attributes is in some cases fairly subjective. Whereas gender and location are verifiable, the choice of whether an individual is an international policy actor or a national policy actor must be inferred from their official role during the crisis period. Sometimes this can be based on the identity of their home institution. Given DFID's central focus on overseas development assistance, its officials have been classified as internationals, rather than nationals. In some cases, individuals may be qualified clinicians or epidemiologists but their role in the crisis may have been primarily policy related and not medical or scientific. Therefore, they are classified as policy actors not scientists. Other demographic attributes could have been identified such as race and age which would have enabled more options for data analysis.

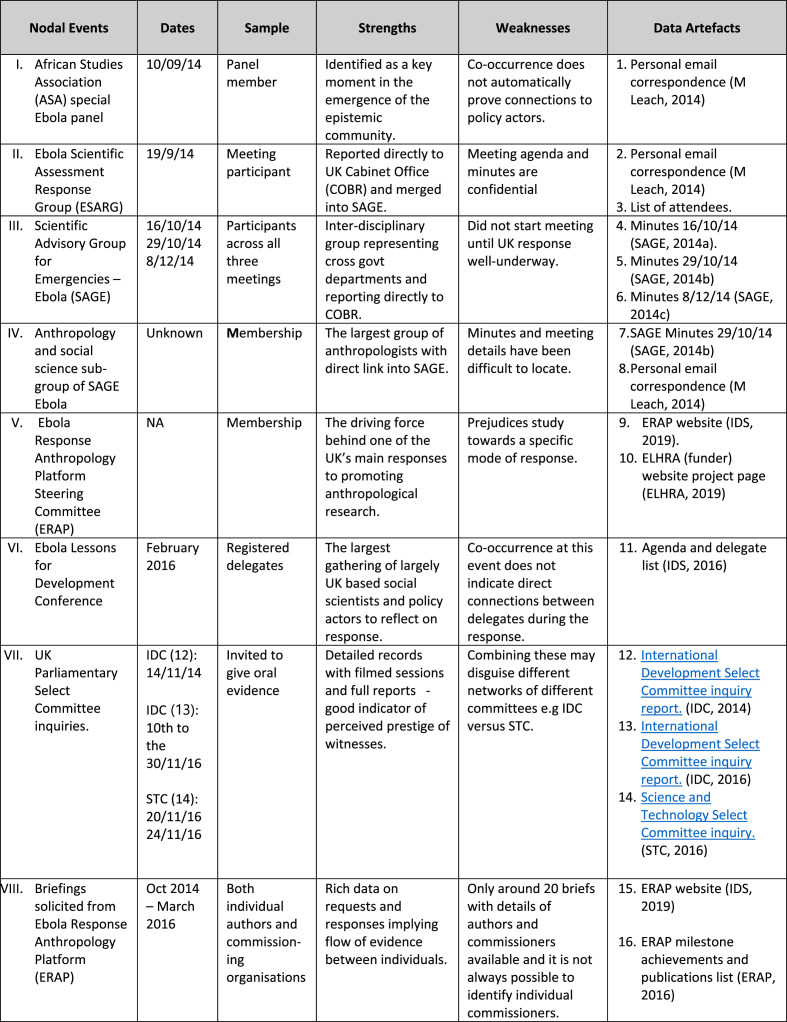

A key factor here is the use of a two mode matrix that identifies connections via people participating in the same events or forums, rather than direct social relationships such as friendship. Therefore, measurement validity is largely determined by whether connections of this type can be used to determine how knowledge and expertise flow between individuals. To mitigate the risk that this measurement fails to capture knowledge exchange toward policy processes, particular care was taken with the sampling of focal events used to generate the network. The majority of errors in SNA relate to the omission of nodes or ties. Fig. 1 sets out the advantages and disadvantages of each of the selected events and the data artefacts used to identify associated individuals.

Fig. 1.

Sampling of focal events/interactions (ELHRA, 2019, IDC, 2014, IDS, 2019, SAGE, 2014b, SAGE, 2014c).

I am aware that some critics might take exception to my choice of network. It is sometimes suggested that by focusing on Northern dominated networks or the actions of bilaterals and multilaterals, you simply reinforce coloniality and a racist framing of development and aid (Richardson et al., 2016) and (Richardson, 2019). However, there is a valid, even essential, purpose here. Only by seeking to understand the politics of knowledge and the social and political dynamics of global health and humanitarian networks can we challenge injustice and historically reinforced narratives that favour some perspectives over others.

2. Results

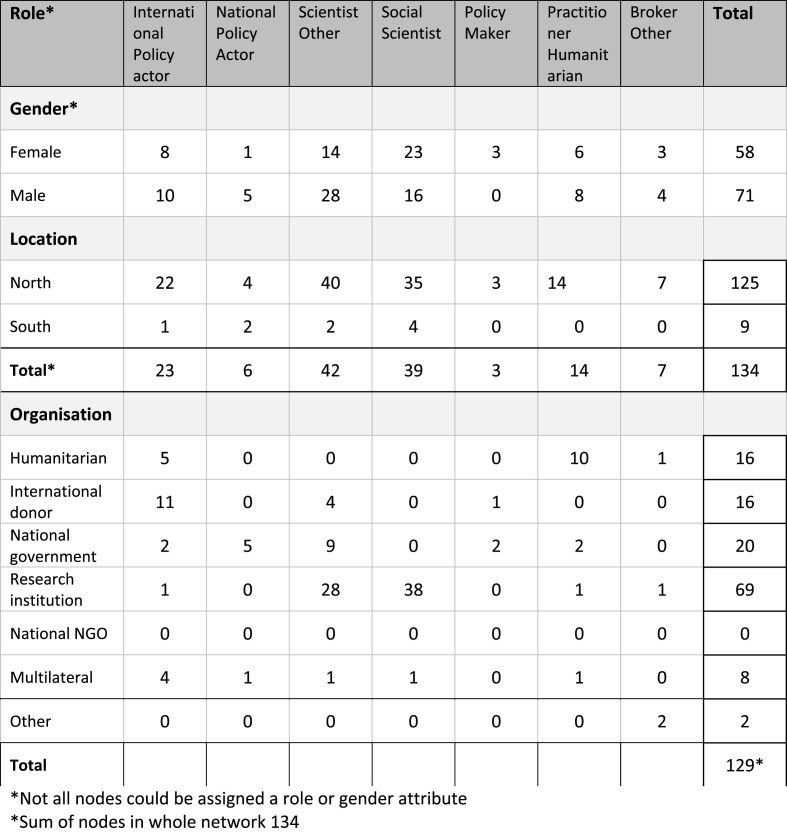

The secondary sources identify 134 unique individuals, all but five of whom can be identified by name. Four types of attribute are assigned to these nodes: gender, location (global north or south), organisation type and organisational role. Attributes have been identified through an internet search of institutional websites, LinkedIn and related online resources. Role and organisation type are recorded for the period of the crisis. The total number of nodes given at the bottom of Fig. 2 is slightly lower due to the anonymity of five individuals whose gender and role could not be established. Looking at this distribution of attributes across the whole network one can make the following observations in relation to how prominently different characteristics are represented:

-

I.

Females slightly outnumber males in the social science category but there are twice as many male ‘scientists other’ than female. They are a combination of clinicians, virologists, epidemiologists and other biomedical expertise.

-

II.

There are just nine southern based nodes out of a total of 134 and none of these are policy makers or practitioners. This is racially and geographically a northern network with just a sliver of West African perspectives. These included, Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, veteran Ebola campaigner and current Mayor of Freetown, four academics from Njala University and development professionals working in the Sierra Leone offices of agencies such as the UNFAO.

-

III.

Although ‘scientists other’ only just outnumber social scientists this is heavily skewed by one of the eight interaction nodes – the Lessons for Development Conference – which was primarily a learning event and not part of the advisory processes around the response. Many individuals who participated in this event are not active in any of the other seven interactions. If we remove these non-active nodes from the network, you get just 23 social scientists compared to 32 ‘scientist other’. The remaining core policy network of 77 individuals appears to be weighted towards the biomedical sciences.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of expertise in UK response to Ebola in Sierra Leone.

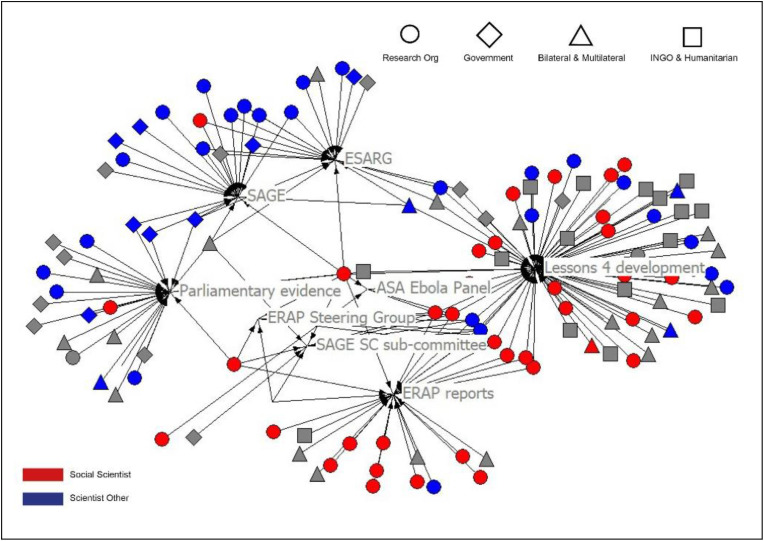

2.1. Clusters of nodes by discipline and organisational affiliation

Netdraw's standardised graph layout algorithm has been used in Fig. 3 to optimise distances between nodes which helps to visualise cohesive sub-groups or sub-networks and produces a less cluttered picture (S. Borgatti and Everet, 2002). However, it should be noted that graph layout algorithms provide aesthetic benefits at the expense of attribute based or values based accuracy. The exact length of ties between nodes and their position do not correspond exactly to the quantitative data. We can drag one of these nodes into another position to make it stand out more clearly without changing its mathematical or sociological properties (S. P. Borgatti et al., 2018).

Fig. 3.

UK research-policy interactions - Ebola Outbreak 2014-16.

We can see in this graph layout the clustering of the eight interactive nodes or focal events and observe some patterns in the attributes of the nodes closest to them. The right-hand side is heavily populated with social scientists. As mentioned above, this is influenced by the Lessons for Development event. As you move to the left side fewer social scientists are represented and they are outnumbered by other disciplines. The State owned or driven interactions such as SAGE and Parliamentary Committees appear on this left side and the anthropological epistemic community driven or owned interactions, such as ERAP reports and Lessons for Development, appear on the right side. The apparent connectors or bridges are in the centre. These bridges can be conceptualised as both focal events, including the ERAP Steering Committee, the SAGE social science sub-committee and the ASA Ebola panel, or as the key individual nodes connected to these. We know that many informal interactions between researchers, officials and humanitarians are not captured here. We are only seeing a partial picture of the network, traces of which remain preserved in documents pertaining to the eight nodal events sampled. Nonetheless, so far the quantitative data seem to correspond closely with the qualitative accounts of the crisis.

Also, of interest is the visual representation of organisation affiliation. All bar one of the 39 social scientists (in the whole network – Fig. 3) are affiliated to a research organisation, whereas one third of the members of other scientific disciplines are attached to government institutions, donors or multilaterals. These are the public health officials and virologists working in the DoH, PHE and elsewhere. They appear predominantly on the left side with much stronger proximity to government led initiatives. However, it is also clear that whilst social scientists are a small minority in the government led events, the right side of the graph includes a significant number of practitioners, policy actors and clinicians. It is this part of the network that most closely resembles an inter-epistemic community. For the centrally located bridging nodes we can see a small number of social scientists and policy actors embedded in government. As accounts of the crisis have suggested these individuals appear to have been the super-connectors.

A final point of clarification is that this is not a map showing the actual knowledge flow between actors during the crisis. Each of the spider shaped sub-networks represent co-occurrence of individuals on committees, panels and other groups. We can infer from this some likelihood of knowledge exchange but we cannot measure this. One exception to these co-occurrence types of tie between nodes are the ERAP reports (bottom right), which reveals a cluster of nodes who contributed to reports along with those who requested them. Even though this represents a knowledge flow of sorts we can still only record the interaction and make assumptions about the actual flow of knowledge.

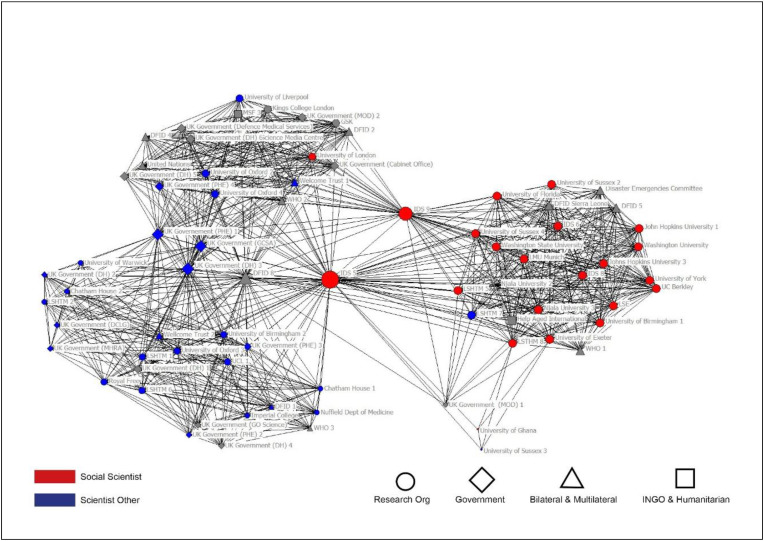

2.2. Degree centrality

A variation of degree centrality, Eigenvector Centrality, counts the number of nodes adjacent to a given node and weighs each adjacent node by its centrality. The Eigenvector equation, used by Netdraw, calculates each node's centrality proportionally to the sum of centralities of the nodes it is adjacent to (S. Borgatti and Everet, 2002). Netdraw increases the size of nodes in relation to their popularity or eigenvector value. The better connected nodes are to others who are also well connected the larger the nodes appear (S. P. Borgatti et al., 2018).

In order to focus on the key influencers or knowledge brokers in the network, we entirely remove nodes solely connected to the Lessons for Development Conference. As mentioned earlier, this event is a poor proxy for research-policy interactions and unduly over-represents social scientists who were otherwise unconnected to advisory or knowledge exchange activities. This reduces the number of individuals in the network from 134 to 77. We also utilise UCINet's Transform function to convert the two-mode incidence matrix into a one mode adjacency matrix (S. Borgatti et al., 2002). Ties between nodes are now determined by connections through co-occurrence. We no longer need to see the events and committees themselves but can visualise the whole network as a social network of connected individuals. We can now observe and mathematically calculate, how inter-connected or homogeneous this research-policy network really is.

We see in Fig. 4 a more exaggerated separation of social science and other sciences on the right and left of the graph than in Fig. 3. We can also see three distinct sub-networks emerging, bridged by six key nodes with high centrality values. The highly interconnected sub-network on the right is shaped in part by ERAP and the production of briefings and their supply to a small number of policy actors. We can see here the visualisation of slightly higher centrality scores than for the government scientific advisors on the left. By treating this as a relational network we observe that interactions like the establishment of a SAGE sub-group for social scientists increased the homophily of the right side of the network and reduced its interconnectivity with the whole network. Although, one must be cautious about assigning too much significance to the position of individual nodes in a whole network analysis, the central location of the two social scientists and a DFID official closely correspond to the accounts of the crisis. This heterogeneous brokerage demonstrates the tendency of certain types of actors to be the sole link between dissimilar nodes (Hamilton et al., 2020). Likewise, some boundary nodes or outliers, such as one of the MOD's advisors at the bottom of the network, are directly mentioned in the qualitative accounts. Just four individuals in this whole network are based in Africa, suggesting almost complete isolation from humanitarians operating on the ground and from African scholarship.

Fig. 4.

UK research-policy network: 2014-16 Sierra Leone Ebola outbreak.

2.3. A partially connected interdisciplinary response

Both the qualitative accounts of the role of anthropologists in the crisis and the whole network analysis presented here largely, correspond with Haas’ definition of epistemic communities. The international community of anthropologists and medical anthropologists that mobilised in Autumn 2014 do indeed share common principles and analytical and normative beliefs. Debates around issues, such as the level to which communities could reduce transmission rates themselves, did not prevent this group from providing a coherent response to the key policy dilemmas. This community did indeed emerge or coalesce around the demand placed on their expertise by policy makers concerned with the community engagement dimensions of the response.

In the area of burial practices, there does appear to be some indication of the knowledge of social scientists being incorporated into the response. Various interactions between anthropologists, DFID and the WHO did provide the opportunity to raise the socio-political-economic significance of funerals. For example, it was explained that the funerals of high status individuals would be much more problematic in terms of the numbers of people exposed (F. Martineau et al., 2017). Anthropologists contributed to the writing of the WHO's guidelines for safe and dignified burials (WHO, 2014b). However, their advice was only partially incorporated into these guidelines and the wider policies of the WHO at the time. The suggestion for a radical decentralised approach to formal burial response that would require the creation of community-based burial teams was ignored until much later in the crisis and never fully implemented.

As Loblova and Dunlop suggest in their critique of epistemic community theory, the extent to which anthropology could influence policy was bounded by the beliefs and understanding of policy communities themselves (Löblová, 2018) and (Dunlop, 2017). Olga Loblova argues that there is a selection bias in the tendency to look at case studies where there has been a shift in policy along the lines of the experts' knowledge. Likewise, Claire Dunlop suggests that Haas’ framework may exaggerate their influence on policy. She separates the power of experts to control the production of knowledge and engage with key policy actors from policy objectives themselves. She refers to adult education literature and its implications for what decision makers learn from epistemic communities, or to put it another way, the cognitive influence of research evidence (Dunlop, 2009). She argues that the more control that knowledge exchange processes place with the “learners” in terms of framing, content and the intended policy outcomes, the less influential epistemic communities will be (Dunlop, 2017).

Hence, in contested areas such as home care, it was the more embedded and credible clinical epistemic community that prevailed. From October 2014, anthropologists were arguing that given limited access to ETUs, which were struggling at that time, home care was an inevitability and so should be supported. Where they saw the provision of home care kits as an ethical necessity, many clinicians, humanitarians and global health professionals regarded home care as deeply unethical with the potential to lead to a two tier system of support (F. Martineau et al., 2017) and (Whitty et al., 2014). In Sierra Leone, Irish diplomat Sinead Walsh was baffled by what she saw as the blocking of the distribution of home care kits. An official from the US Centres for Disease Control and Protection (CDC) was quoted in an article in the New York Times as saying that home care was: “admitting defeat” (Nossiter, 2014) in (Walsh and Johnson, 2018). Home care was never prioritised in Sierra Leone whereas in Liberia hundreds of thousands of kits were distributed (Walsh and Johnson, 2018). In this area, clinicians, humanitarians and policy actors seemed to maintain a policy position directly opposed to anthropological based advice.

Network theory provides further evidence around why this may have been the case. In his study of UK think tanks, Jordan Tchilingirian suggests that policy think tanks operate on the periphery of more established networks and enjoy fluctuating levels of support and interest in their ideas. Ideas and knowledge do not simply flow within the network, given that dominant paradigms and political, social and cultural norms privilege better established knowledge communities (Tchilingirian, 2018). This is reminiscent of Meyer's work on the boundaries that exist between “amateurs” and “policy professionals” (Meyer, 2008). Moira Faul's research on global education policy networks proposes that far from being “flat,” networks can augment existing power relations and knowledge hierarchies (Faul, 2016). This is worth considering when one observes how ERAP's supply of research knowledge and the SAGE sub-committee for anthropologists only increased the homophily of the social science sub-community, leaving it weakly connected to the core policy network (Fig. 4.).

The positive influence of anthropological advice on the UK's response was cited by witnesses to the subsequent Parliamentary Committee inquiries in 2016. However, there is some indication of different groups or networks favouring different narratives. The International Development Select Committee (IDC) was very clear in its final report that social science had been a force for good in the response and recommended that DFID grow its internal anthropological capacity (IDC, 2016a, b). This contrasts to the report of the Science and Technology Committee (STC), which despite including evidence from at least one anthropologist, does not make a direct reference to anthropology in its report (STC, 2016). This is perhaps the public health officials in their core domain of infectious disease outbreaks reasserting their established authority. This sector has been described as the UK's “Biomedical Bubble” which benefits from much higher pubic support and funding than the social sciences (Jones and Wilsdon, 2018). Just the presence of anthropologists in an evidence session of the STC is a very rare event in contrast to the IDC which regularly reaches out to social scientists. Not everyone agrees that the threat of under-investing in social science was the primary issue. The STC's report highlights the view that there was a lack of front line clinicians represented on committees advising the UK Government, particularly from aid organisations (STC, 2016).

Regardless of assessments of how successfully anthropological knowledge influenced policy and practice during the epidemic, there has been a subsequent elevation of social science in global health preparedness and humanitarian response programmes. Writing on behalf of the Wellcome Trust in 2018, João Rangel de Almeida says: “epidemics are a social phenomenon as much as a biological one, so understanding people's behaviours and fears, their cultural norms and values, and their political and economic realities is essential too.” (Rangel de Almeida, 2018). The Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform, which involves many of the same researchers who were part of the Sierra Leone response, has subsequently been supported by UNICEF, USAID and Joint Initiative on Epidemic Preparedness (JIEP) with funding from DFID and Wellcome. Its network of social science advisers have been producing briefings to assist with the Ebola response in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (Farrar, 2019) and have mobilised in response to the Covid-19 respiratory illness epidemic.

3. Conclusions

Network theory provides a useful framework with which to explore the politics of knowledge in global health with its emphasis on individuals' social context. By analysing data pertaining to researchers' and policy professionals' participation in policy networks one can test assumptions around interdisciplinarity and identify powerful knowledge gatekeepers. Detailed qualitative accounts of policy processes needn't be available, as they were in this case, to employ this methodology. Assuming the researcher has access to meeting minutes and other records of who attended which events or who was a member of which committees and groups, similar analysis of network homophily and centrality will be possible. The greatest potential for learning, with significant policy and research implications, comes from mixed methods approaches. By combining qualitative research to populate your network with a further round of data gathering to understand it better, you can reveal the social and political dynamics truly driving evidence use and decision making (Oliver and Faul, 2018). Although this study lacked this scope, it has still successfully identified the shape of the research-policy network that emerged around the UK led response to Ebola and the clustering of actors within it.

The network was a diverse group of scientists, practitioners and policy professionals. However, it favoured the views of government scientists with their emphasis on epidemiology and the medical response. It was also almost entirely lacking in West African members. Nonetheless, it was largely thanks to a strong political demand for anthropological knowledge, in response to perceived community violence and distrust, that social scientists got a seat at the table. This was brokered by a small group of individuals from both government and research organisations, who had prior relationships to build on. The emergent inter-epistemic community was only partially connected into the policy network and we should reject the description of the whole network as trans-disciplinary. Social scientists were most successful in engaging when they framed their expertise in terms of already widely accepted concepts, such as the need for better communications with communities. They were least successful when their evidence countered strongly held beliefs in areas such as home care. Their high level of homophily as a group, or sub network, only deepened the ability of decision makers to ignore them when it suited them to do so.

The epistemic community's interactivity with UK policy did not significantly alter policy design or implementation and it did not challenge fundamentally eurocentric development knowledge hierarchies. It was transformative only in as much as it helped the epistemic community itself learn how to operate in this environment. The real achievement has been on influencing longer term evidence use behaviours. They made the case for interdisciplinarity and the value of social science in emergency preparedness and response. The challenge now is moving from the rhetoric to action on complex infectious disease outbreaks. As demonstrated by Ebola in DRC and Covid-19, every global health emergency we face will have its own unique social and political dimensions. We must remain cognisant of the learning arising from the international response to Sierra Leone's tragic Ebola epidemic. It suggests that despite the increasing demand for interdisciplinarity, social science evidence is frequently contested and policy networks have a strong tendency to leave control over its production and use in the hands of others.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

James Georgalakis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Visualization.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr Jordan Tchilingirian (University of Western Australia) for discussions and support on UCINet. I thank Professor Melissa Leach and Dr Annie Wilkinson (Institute of Development Studies) for access to archival data.

References

- Abramowitz S. Epidemics (especially Ebola) Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2017;46:421–445. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz S.A., Bardosh K.L., Leach M., Hewlett B., Nichter M., Nguyen V.-K. Social science intelligence in the global Ebola response. Lancet. 2015;385:330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardosh K. One health : science, politics and zoonotic disease in Africa. In: Bardosh K., editor. Routledge; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benton A. Ebola at a distance: a pathographic account of anthropology's relevance. Anthropol. Q. 2017;90:495–524. [Google Scholar]

- Berghs M. ERAP; 2014. Stigma and Ebola: an Anthropological Approach to Understanding and Addressing Stigma Operationally in the Ebola Response. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti S., Everet M. 2002. Netdraw. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti S., Everet M., Freeman L. Analytic Technologies; Harvard: MA: 2002. UCINET 6 for Windows. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti S.P., Everett M.G., Johnson J.C. Sage; 2018. Analyzing Social Networks. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley N., Edwards G. Cases, mechanisms and the real: the theory and methodology of mixed-method social network analysis. Socio. Res. Online. 2016;21:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Delpla I., Fassin D. La raison humanitaire. Une histoire morale du temps present. In: Fassin D., Delpla I., editors. 2012. pp. 165–167. [Google Scholar]

- DFID . 2014. INTERNATIONAL CALL FOR ASSISTANCE TO COMBAT EBOLA FROM THE GOVERNMENTS OF SIERRA LEONE AND THE UNITED KINGDOM. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop C.A. Policy transfer as learning: capturing variation in what decision-makers learn from epistemic communities. Pol. Stud. 2009;30:289–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop C.A. The irony of epistemic learning: epistemic communities, policy learning and the case of Europe's hormones saga. Policy Soc. 2017;36:215–232. [Google Scholar]

- ELHRA . 2019. Ebola Response Anthropology Platform. [Google Scholar]

- ERAP . LSTHM; 2016. ERAP Milestone Achievements up until Feb 2016. IDS. [Google Scholar]

- ESRC . ESRC; 2016. Ebola Response with Local Engagement. [Google Scholar]

- Fairhead J. HEART; 2014. Ebola- Local Beliefs and Behaviour Change. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar J. 2019. The global community must unite to intensify Ebola response in the DRC. (Linked In) [Google Scholar]

- Faul M.V. Networks and power: why networks are hierarchical not flat and what can be done about it. Global Policy. 2016;7:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck F. The human factor. World Health Organization. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015;93:72–73. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa J. Finding the spaces for change: a power analysis. IDS Bull. 2006;37:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Georgalakis J., Rose P. Introduction: identifying the qualities of research–policy partnerships in international development–A New analytical framework. IDS Bull. 2019;50:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Haas P.M. Introduction: epistemic communities and international policy coordination. Int. Organ. 1992;46:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hagel C., Weidemann F., Gauch S., Edwards S., Tinnemann P. Analysing published global Ebola Virus Disease research using social network analysis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M., Hileman J., Bodin Ö. Evaluating heterogeneous brokerage: New conceptual and methodological approaches and their application to multi-level environmental governance networks. Soc. Network. 2020;61:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- HEART . Education Advice and Resource Team; 2019. Health. [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett B.S., Hewlett B.L. Cengage Learning; 2007. Ebola, Culture and Politics: the Anthropology of an Emerging Disease. [Google Scholar]

- IDC . House of Commons; London: 2014. Responses to the Ebola Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- IDC . House of Commons; London: 2016. Ebola: Responses to a Public Health Emergency. [Google Scholar]

- IDS . 2016. Ebola Lessons for Development Conference - Agenda and Delegates. [Google Scholar]

- IDS . 2019. Ebola Response Anthropology Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R., Wilsdon J.R. University of Sheffield; 2018. The Biomedical Bubble: Why UK Research and Innovation Needs a Greater Diversity of Priorities, Politics, Places and People. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S.B., Nisbett R.A. SciELO Public Health; 2015. The Ebola epidemic: a transformative moment for global health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach, M. (2014). (Email correspondence).

- Leach M., Wilkinson A., Fairhead J., Kelly A., Richards P., Parker M. 2016. Ebola: Engaging Long-Term Social Science Research to Transform Epidemic Response. [Google Scholar]

- Löblová O. When epistemic communities fail: exploring the mechanism of policy influence. Pol. Stud. J. 2018;46:160–189. [Google Scholar]

- LSHTM . 2015. Online course: Ebola in context: understanding transmission, response and control. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau F., Wilkinson A., Parker M. Epistemologies of Ebola: reflections on the experience of the Ebola response anthropology platform. Anthropol. Q. 2017;90:475–496. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M. On the boundaries and partial connections between amateurs and professionals. Mus. Soc. 2008;6:38–53. [Google Scholar]

- MSF . MSF; 2015. Pushed to the Limit and beyond. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale D.J., Cromby J. Social constructionism as ontology: exposition and example. Theor. Psychol. 2002;12:701–713. [Google Scholar]

- Nossiter A. A City Swamped with Eobla. New York Times; 2014. A hospital from hell. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K., Faul M.V. Networks and network analysis in evidence, policy and practice. Evid. Policy A J. Res. Debate Pract. 2018;14:369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhoff P. IDS; 2015. Ebola Crisis Appeal Response Review. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel de Almeida J. Wellcome; 2018. Social Science Research: a Much-Needed Tool for Epidemic Control. [Google Scholar]

- redrUK . redrUK; 2014. Pre-Departure Ebola Response Training. [Google Scholar]

- Richards P. ERAP Briefing: ERAP; 2014. Burial/Other Cultural Practices and Risk of EVD Transmission in the Mano River Region. [Google Scholar]

- Richards P. ERAP; 2014. Burial/Other Cultural Practices and Risk of EVD Transmission in the Mano River Region. [Google Scholar]

- Richards P. Zed Books Ltd; 2016. Ebola: How a People's Science Helped End an Epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson E.T. On the coloniality of global public health. Med. Anthropol. Theor. 2019;6:101–118. doi: 10.17157/mat.6.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson E.T., Barrie M.B., Kelly J.D., Dibba Y., Koedoyoma S., Farmer P.E. Biosocial approaches to the 2013-2016 Ebola pandemic. Health Hum. Rights. 2016;18:115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAGE . 2014. Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies - Ebola Summary Minute of 1st Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- SAGE . 2014. Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies - Ebola Summary Minute of 2nd Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- SAGE . 2014. Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies - Ebola Summary Minute of 3rd Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- STC . House of Commons; 2016. Science in Emergencies: UK Lessons from Ebola. [Google Scholar]

- Stovel K., Shaw L. Brokerage. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2012;38:139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tchilingirian J.S. Producing knowledge, producing credibility: British think-tank researchers and the construction of policy reports. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 2018;31:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Victor J.N., Montgomery A.H., Lubell M. Oxford University Press; 2017. The Oxford Handbook of Political Networks. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S., Johnson O. Zed Books; 2018. Getting to Zero: A Doctor and a Diplomat on the Ebola Frontline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M., Stovel K., Sacks A. Network analysis and political science. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2011;14:245–264. [Google Scholar]

- West T.E., von Saint André-von Arnim A. Clinical presentation and management of severe Ebola virus disease. Ann. Am. Thoracic Soc. 2014;11:1341–1350. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-481PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitty C.J., Farrar J., Ferguson N., Edmunds W.J., Piot P., Leach M. Infectious disease: tough choices to reduce Ebola transmission. Nat. News. 2014;515:192. doi: 10.1038/515192a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2014. Ebola Situation in Liberia: Non-conventional Interventions Needed. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . WHO; 2014. Field Situation: How to Conduct Safe and Dignified Burial of a Patient Who Has Died from Suspected or Confirmed Ebola Virus Disease. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2014. Key Messages for Social Mobilization and Community Engagement in Intense Transmission Areas. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A., Fairhead J. Comparison of social resistance to Ebola response in Sierra Leone and Guinea suggests explanations lie in political configurations not culture. Crit. Publ. Health. 2017;27:14–27. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2016.1252034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood V. Coronavirus: China president warns spread of disease ‘accelerating’, as Canada confirms first case. The Independent. 2020 [Google Scholar]