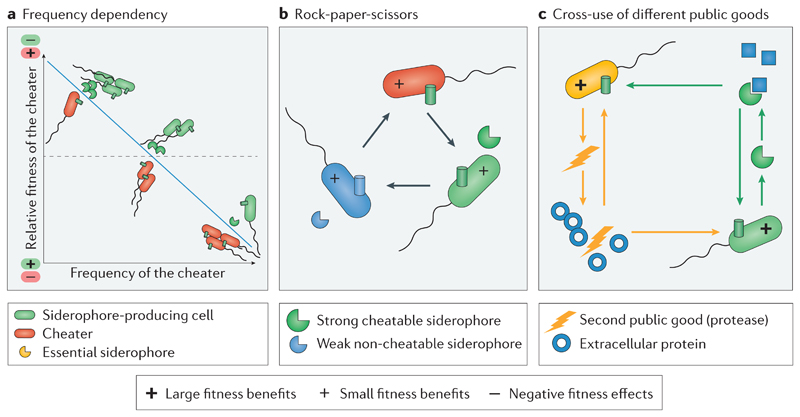

Figure 5. Siderophores induce eco-evolutionary dynamics in bacterial communities.

a | If siderophores (yellow partial circles) are essential for growth, siderophore producers (green cells) and non-producing cheaters (red cells) can co-exist in a community through negative frequency-dependent selection. b | Strains or species with different siderophore strategies can engage in non-transitive community dynamics, and thereby co-exist and foster biodiversity. The example depicts interactions between a cheater (red) outcompeting the siderophore producer, which secretes a compatible siderophore (green). This siderophore producer in turn outcompetes the second siderophore producer (blue), secreting a less potent siderophore. This weaker siderophore producer, however, outcompetes the non-producer because it produces a siderophore for which the non-producer lacks the matching receptor. This scenario leads to a rock-paper-scissors dynamic, in which strains chase each other in circles with no overall winner. c | When, in addition to siderophores (green partial circles), a second public good is important for growth (yellow flash, for example, proteases required for extra-cellular protein degradation), specialization could evolve, leading to each strain or species producing only one public good and exchange at the community level. Emojis inside cells depict the relative fitness consequences for the interacting partners.