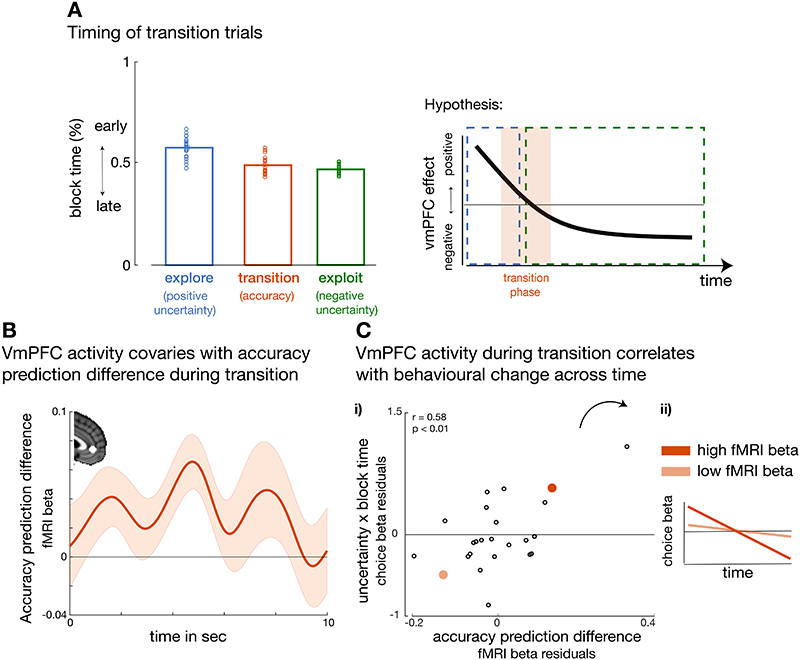

Figure 7. Accuracy processing mediates uncertainty polarity change from exploration to exploitation.

(A)Transition trials (Supplementary Figure 9A) occurred later than exploratory selections and earlier than exploitative selections (left panel) (explore vs transition: t(23)=6, p<0.001, d=1.2, 95%confidence interval= [0.056 0.12]; transition vs exploit: t(23)=-2.8, p=0.01, d=-0.57, 95%confidence interval= [-0.04 -0.006]). We hypothesized activation in vmPFC to be correlated with positive uncertainty, accuracy and negative uncertainty prediction differences between predictors, but at different times during the experiment (see illustration, right panel). (B) During transition trials, activation in vmPFC covaried with the difference in the accuracy between the chosen and unchosen predictor, i.e. accuracy prediction difference (t(23) = 3.5, p= 0.002, d=0.71,95% confidence interval=[0.03 0.1]. (C-i) Participants who showed a stronger vmPFC accuracy prediction difference during the transition period (variability around time course peak from panel b), also integrated more drastically the uncertainty between predictors across time into their choice behaviour (uncertainty × block time from Figure 3A; r= 0.58, p= 0.007, 95% confidence interval=[0.23 0.8]). (ii) For illustration, this means that participants with stronger accuracy-related vmPFC activation had a stronger change in integrating uncertainty across time, i.e. a stronger slope in the uncertainty × block time effect. The illustration depicts two example participants, dark orange indicates a subject with both a strong vmPFC accuracy activation and pronounced behavioural change in how uncertainty was used to drive choice behaviour. By contrast, the participant indicated in light orange shows a weak vmPFC BOLD accuracy effect and only a small change in how uncertainty was used over time. These findings support the idea that the transition between positive uncertainty-driven exploration to negative uncertainty-driven exploitation is mediated by representing the accuracy between predictors. (n = 24; error bars are SEM across participants).