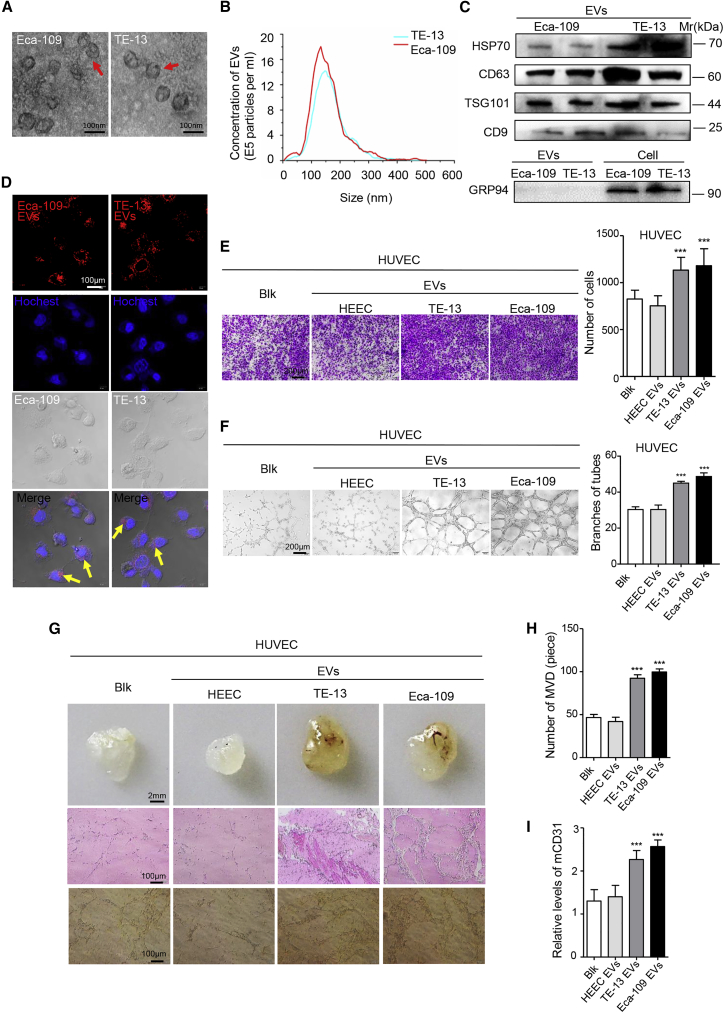

Figure 1.

EVs Secreted from ESCC Cells Contribute to Angiogenesis In Vitro and In Vivo

(A) EVs released by Eca-109 and TE-13 cells were observed by electron microscopy. Scale bars, 100 nm. (B) The concentration of EVs was detected by NanoSight particle tracking analysis. (C) Indicated proteins in EVs were detected by western blot. (D) The delivery of PKH26-labeled (red) EVs to Hoechst-labeled HUVECs (blue) was shown by confocal imaging. Yellow arrows represented delivered EVs, and representative images were presented. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Migration assays of HUVECs treated with equal quantities of EVs derived from HEEC and ESCC cell lines or blank control. Migrated cells were counted, and representative images were shown. Scale bar, 200 μm. (F) Tube formation assays of HUVECs treated with equal quantities of EVs derived from HEEC and ESCC cell lines or blank control. Branches of tubes were counted, and representative images were shown. Scale bar, 200 μm. (G) Matrigel mixed with ESCC-derived EVs or PBS was subcutaneously injected into nude mice (n = 5). After 14 days, the Matrigel plugs were harvested and performed by hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry for CD31. Representative micrographs were shown. Scale bars, 2 mm (top panels); 100 μm (middle and bottom panels). (H) The number of microvessel density (MVD) significantly increased in the Matrigel plugs containing ESCC-derived EVs. (I) The expression of mouse CD31 was significantly increased in the Matrigel plugs containing ESCC-derived EVs. Experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and results are shown as mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used to analyze the data. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.