Abstract

The pineal gland is a neuroendocrine organ responsible for production of the nocturnal hormone melatonin. A specific set of homeobox gene-encoded transcription factors govern pineal development, and some are expressed in adulthood. The brain-specific homeobox gene (Bsx) falls into both categories. We here examined regulation and function of Bsx in the mature pineal gland of the rat. We report that Bsx is expressed from prenatal stages into adulthood, where Bsx transcripts are localized in the melatonin-synthesizing pinealocytes, as revealed by RNAscope in situ hybridization. Bsx transcripts were also detected in the adult human pineal gland. In the rat pineal gland, Bsx was found to exhibit a 10-fold circadian rhythm with a peak at night. By combining in vivo adrenergic stimulation and surgical denervation of the gland in the rat with in vitro stimulation and transcriptional inhibition in cultured pinealocytes, we show that rhythmic expression of Bsx is controlled at the transcriptional level by the sympathetic neural input to the gland acting via adrenergic stimulation with cyclic AMP as a second messenger. siRNA-mediated knockdown (>80% reduction) in pinealocyte cultures revealed Bsx to be a negative regulator of other pineal homeobox genes, including paired box 4 (Pax4), but no effect on genes encoding melatonin-synthesizing enzymes was detected. RNA sequencing analysis performed on siRNA-treated pinealocytes further revealed that downstream target genes of Bsx are mainly involved in developmental processes. Thus, rhythmic Bsx expression seems to govern other developmental regulators in the mature pineal gland.

Keywords: Bsx, pineal gland, rat, human, circadian, homeobox, siRNA, RNA sequencing, RNAscope

Introduction

The mammalian pineal gland secretes the nocturnal hormone melatonin, which is synthesized from tryptophan by the action of the pineal enzymes tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT), and acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (ASMT)1. Rhythmic melatonin synthesis in the pineal gland is controlled by the circadian clock of the hypothalamus, i.e. the suprachiasmatic nucleus, via sympathetic nerve fibers originating from the superior cervical ganglia (SCG) which release norepinephrine (NE) in the gland at night2. This rhythmic adrenergic input induces transcription and activation of AANAT resulting in nocturnal melatonin synthesis1,3.

Development of the pineal gland is controlled by a specific set of homeobox gene-encoded transcription factors4–6. However, as a special feature of the pineal gland, a number of homeobox genes continue to be expressed into adulthood or are even restricted to the postnatal gland4,5,7–9. To this end, we have shown that certain pineal homeobox genes are involved in transcriptional regulation of the enzymes of the melatonin synthesis pathway and that rhythmic expression of these transcription factors is also controlled by the adrenergic input to the gland10–12.

The brain-specific homeobox gene (Bsx) is expressed in the developing pineal gland at early stages and is essential for proper pineal morphogenesis in both mice, frogs (Xenopus) and zebrafish13–16. In the postnatal rodent brain, Bsx is specifically expressed in the pineal gland and the hypothalamus14. Large screening efforts have previously identified Bsx as being expressed in the mature rat pineal gland with high levels during nighttime and regulated by sympathetic adrenergic signaling17; in addition, RNA sequencing studies have detected adult pineal expression of Bsx in zebrafish, chicken, and several mammals (https://snengs.nichd.nih.gov). However, circadian and developmental expression patterns, cellular localization, and regulatory functions of Bsx in the postnatal mammalian pineal gland remain to be established. In this study, we employed histological and molecular biological techniques to identify the role of Bsx in the adult pineal gland.

Materials and methods

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats (timed-pregnant mothers or 180 to 220g adult males) obtained from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany) or from Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) were housed under a 12h light: 12h dark (12L:12D) schedule. Euthanasia was performed at indicated Zeitgeber times (ZT) or circadian times (CT) by anesthesia with CO2 followed by decapitation; during dark conditions, euthanasia was carried out under dim red light. For the developmental series, heads (embryonic day 15 (E15) to postnatal day 2 (P2)) or whole brains (P10 to P30) were removed, immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 days at 4°C, cryoprotected in 25% sucrose, and frozen on crushed solid CO2. For qRT-PCR and in situ hybridization on adult tissue, whole brains, brain parts and peripheral tissues were dissected and immediately frozen on crushed solid CO2. For circadian experiments, animals were transferred to constant darkness (DD) two days prior to euthanasia. Superior cervical ganglionectomy (SCGx) and decentralization of the superior cervical ganglia (SCGdcn) were performed as previously described18. Injection (i.p.) of isoprenaline (10 mg/kg in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)) or PBS was done at ZT5 followed by euthanasia at ZT8. For pineal gland cell cultures, pineal glands dissected from adult male rats (n=12–22, ZT3–5) were pooled and kept in cold high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) until pineal cell isolation. All animal experiments were in accordance with the guidelines of EU directive 2010/63/EU and approved by the Danish Council for Animal Experiments (authorization number 2017–15-0201–01190) and the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen (authorization number P17–311).

Human tissue

Human adult brain sections were obtained from the Human Brain Tissue Bank of Semmelweis University (Budapest, Hungary): #233, pineal gland, male, age 54, time of death 4.25 AM, heart failure; #249, pineal gland, male, age 22, time of death 23.10 PM, suicide; #273, hypothalamus, male, age 64, time of death unknown, stroke. Procedures were approved by the Regional and Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics of Scientific Council of Health (34/2002/TUKEB-13716/2013/EHR, Budapest, Hungary) and the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Radiochemical in situ hybridization

Cryostat brain sections (adult rats, 12 µm; developmental series, 14 µm; human tissue, 18 µm) were hybridized with [35S]dATP-labelled antisense DNA probes specific for human or rat Bsx mRNA (Table 2), as previously described19. Hybridized sections were washed, exposed to an X-ray film for 16 to 21 days, and developed. The X-ray films were digitized; optical densities were quantified using Scion Image Beta 4.0.2 (Scion, Frederick, MD, USA) and converted to dpm/mg tissue by using simultaneously exposed 14C-standards. Sections were counter-stained in cresyl violet.

Table 2.

Radiochemical and RNAscope in situ hybridization probes.

| Transcript | Species | Genbank acc. # | Technique | Position | Probe type / sequence (5´−3´) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bsx | Rat | NM_001191995.1 | Radiochemical | 76-42 | GATGGAGAGGGGAAGTGAAGTTGAGATTCATCTTG |

| RNAscope | 2-856 | 18ZZ probe set | |||

| Human | NM_001098169.1 | Radiochemical | 254-220 | GTGAGGAAATAAGGATGATGGTGGTCTCCCTTATG | |

| Aanat | Rat | NM_012818.2 | RNAscope | 23-1176 | 20ZZ probe set |

RNAscope in situ hybridization

Fresh frozen cryostat brain sections (adult rats, 12 µm) were pretreated and hybridized in accord with the manufacturer’s instructions (ACDBio, Newark, CA; protocols #320513 and #320293). RNAscope in situ hybridization20 was performed by use of the RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit (ACDBio) with probe sets specific for Bsx and Aanat mRNA (Table 2). Sections were photographed in a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam 506 mono camera.

Brightness and contrast were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems Software, San Jose, CA).

Quantitative real-time Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) followed by DNase I treatment (Invitrogen, Taastrup, Denmark). cDNA was synthesized following the Superscript III protocol (Invitrogen) using 500 ng (from tissues) or 250 ng (from cell cultures) of total RNA as starting material. PCR reactions were run in a Lightcycler 96 (Roche Diagnostics, Hvidovre, Denmark) at volumes of 10 µl containing Faststart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche), 0.2 µl cDNA, and 0.5µM transcript-specific primers (Table 1), using the following program: 95°C for 10 minutes; 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds, 63°C for 10 seconds, 72°C for 15 seconds. Product specificity was initially confirmed by melting curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. 10-fold serial dilutions of pUC57 plasmids (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) containing the target sequence were used to generate standard curves. Copy numbers were normalized against those of the housekeeping transcript Gapdh or geometric means of Gapdh and Actb copy numbers.

Table 1.

qRT-PCR primer sequences.

| Transcript | Genbank acc. # | Position | Forward primer sequence (5´−3´) | Reverse primer sequence (5´−3´) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aanat | NM_012818.2 | 525-682 | TGCTGTGGCGATACCTTCACCA | CAGCTCAGTGAAGGTGAGAGAT |

| Actb | NM_031144.3 | 26-184 | ACAACCTTCTTGCAGCTCCTC | CCACGATGGAGGGGAAGAC |

| Asmt | NM_144759.2 | 696-860 | GCAAGACCCAGTGTGAGGTT | CAGTAGTGCACCACCTGGC |

| Bsx | NM_001191995.1 | 231-416 | CACCCTCCTCACCCCTCACAC | CCGGAGAGCTGCGAGTCAGAA |

| Crx | NM_021855.1 | 76-204 | ATGCACCAGGCTGTCCCATA | TGCATACACATCCGGGTACTG |

| Gapdh | NM_017008.4 | 77-386 | TGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGAT | TCCATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGTA |

| Otx2 | NM_001100566.1 | 630-761 | ACCCAGACATCTTCATGCGG | TCTGACCTCCGTTCTGTTGC |

| Pax4 | NM_031799.1 | 674-808 | TGCCTGAAGACACAGTGAGG | TGATCCCTGGAGAATCTTTTGGT |

| Rax | NM_053678.1 | 461-581 | GTGCCTTTGAGAAGTCCCACT | CGTCTCCACTTGGCTCGAC |

| Tph1 | NM_001100634.2 | 702-814 | CAGAAACCTTCCTCTGCTCTCA | CAGGACGGATGGAAAACCCT |

Pineal cell cultures and siRNA-mediated knockdown

Primary pineal cell cultures were prepared as previously described 10 and incubated in aliquots of 100,000 cells per sample. For knockdown experiments, pinealocytes were transfected with siRNA specifically targeting Bsx mRNA (siBsx) (40 nM; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Stealth RNAi Bsx siRNA, catalogue #1330001, targeting position 182–206 on NM_001191995.1) or non-targeting siRNA (siNT) (40 nM; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Stealth RNAi siRNA negative control, catalogue #12935300) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). On the second day, the medium was changed. On the third day, norepinephrine (NE) (3 µM; Sigma-Aldrich, Søborg, Denmark) or dibutyryl-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (DBcAMP) (500 µM; Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the cell media for the indicated durations. For transcriptional inhibition, pineal cell cultures were pretreated with Actinomycin D (30 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1h prior to DBcAMP stimulation. Harvested cells were immediately frozen on crushed solid CO2 and stored at −80°C.

Statistical analyses

Quantitative data analysis of qRT-PCR and in situ hybridization data was performed in Graphpad Prism 8.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni-corrected multiple individual t-tests for the relevant comparisons; individual t-tests were performed as unpaired Student’s or Welch’s t-tests depending on whether the variances of two compared groups could be presumed equal, as determined by F-tests.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA from pineal cell cultures was isolated using TRIzol (Life Technologies) followed by purification and DNase I treatment using a Qiagen RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RNA amount and integrity were assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (RIN > 8) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA); total input was 3.4 ng. cDNA libraries were prepared with Takara SMARTer Stranded Total RNAseq Pico Input Mammalian Kit v2 with unique barcode adapters for each of the six libraries according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara Bio, Mountain View, CA). Sequencing was performed on a single FlowCell on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA), resulting in an average of 68 million 2x100 bp reads per sample. The number of reads per transcript was normalized to the total number of reads; reads were aligned to the rat genome (RefSeq rn6) using the RNA STAR algorithm21. Differential expression analysis was performed in DESeq2 software using Wald tests with Benjamini-Hochberg corrections for False Discovery Rate22. Confidently differentially expressed genes were included in an analysis for transcript overrepresentation using the DAVID gene-annotation enrichment tool where we examined the GOterm Biological Processes at level 5 output after filtering for the following parameters: P<0.001, ≥±25% relative change, base mean ≥100 reads23,24.

Results

Bsx is expressed in the developing rat pineal gland into adulthood

To examine the ontogenetic expression patterns of Bsx, in situ hybridization was performed on coronal brain sections from rats sacrificed at daytime (ZT6) and at nighttime (ZT18) during pre- and postnatal stages ranging from E15 to P30 (Fig. 1). Bsx was detected in the pineal gland at all ages, as reported in other species13,15,16, but was undetectable in other brain regions present in the same coronal plane. Both developmental age and ZT exerted significant effects on Bsx expression in the pineal gland (P<0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Ontogenetic expression of Bsx in the rat brain.

Representative X-ray images of coronal brain sections hybridized for detection of Bsx transcripts at daytime (ZT6, middle) or nighttime (ZT18, right) at the indicated developmental ages. Images of cresyl violet-counterstained brains at ZT6 (left) are shown for comparison. Scale bar, 1 mm. E, embryonic day; P, postnatal day; ZT, Zeitgeber time.

Figure 2. Quantification of Bsx expression in sections of the developing rat brain.

Densitometric analysis of radiochemical in situ hybridization for detection of Bsx transcripts in the developing pineal gland of rats at daytime (ZT6, dashed line) or nighttime (ZT18, solid line) at the indicated ages. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of both developmental age (P<0.0001) and time of day (P<0.00001) on expression of Bsx in the pineal gland. Values on the graph represent mean ± SEM; n=4. ZT, Zeitgeber time.

Bsx is expressed in melatonin-producing pinealocytes of the adult rat pineal gland and exhibits a circadian rhythm

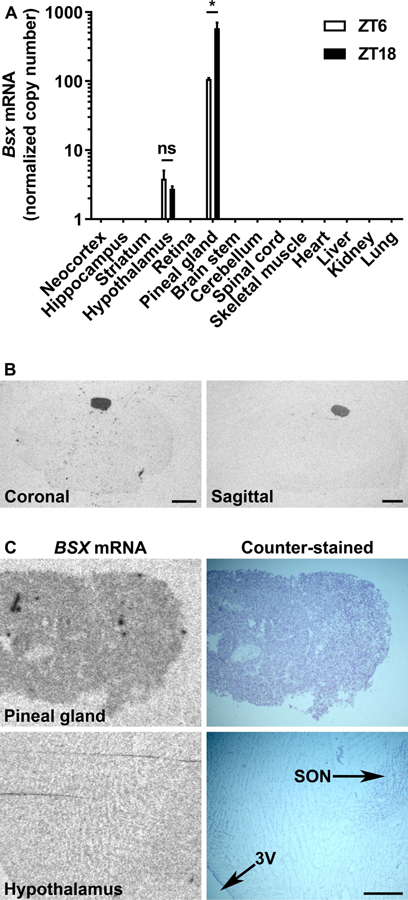

To determine the tissue distribution of Bsx transcripts, qRT-PCR was performed on samples from the central nervous system and peripheral tissues obtained from adult rats sacrificed at ZT6 and ZT18 (Fig. 3A). Bsx mRNA was detectable in the pineal gland and the hypothalamus13,14,25–27; significantly lower levels were detected in the hypothalamus (P<0.001). Pineal Bsx mRNA showed a significant day-night difference with higher levels at ZT18 compared to ZT6 (P<0.05), as previously indicated by RNA sequencing studies17. A day-night difference in hypothalamic Bsx expression was not detected (P>0.05). In situ hybridization on adult rat brain sections confirmed tissue-specific expression in the pineal gland (Fig. 3B). BSX mRNA was further detected in sections of the human pineal gland with a positive signal in the parenchyma; a signal above background was not detected in sections of the hypothalamus containing the supraoptic nucleus, which was used as negative control (Fig. 3C)13,14. Cellular distribution of Bsx in the rat pineal gland was examined by RNAscope in situ hybridization; cells expressing Bsx were present in all parts of the gland and the Bsx signal colocalized with the Aanat signal, showing that Bsx is expressed in melatonin-producing pinealocytes (Fig. 4)

Figure 3. Tissue-specific expression of Bsx in the adult rat and human pineal gland.

A) Quantitative analysis of Bsx transcript levels as determined by qRT-PCR in adult rat tissues obtained at daytime (ZT6) or nighttime (ZT18). Bsx copy numbers were normalized against geometric means of the copy numbers of the housekeeping genes Gapdh and Actb, which were detected in all examined tissues. Values on the Y-axis are shown on a logarithmic scale. Values on the graph represent mean ± SEM; n=3, except for the pineal gland, where n=6 (ZT6) and n=5 (ZT18). Tissue distribution (P<0.001) and ZT (P<0.0001) both exerted significant effects on Bsx mRNA levels in the tissues where it was detected as determined by two-way ANOVA. P-values determined by Bonferroni-corrected Welch’s t-tests: ns, not significant; *, P<0.05. B) Radiochemical in situ hybridization on coronal (left) and sagittal (right) sections for detection of Bsx transcripts in the rat brain. Animals were sacrificed at ZT18. Scale bars, 1 mm. C) Radiochemical in situ hybridization for detection of BSX expression in coronal sections of the human pineal gland (left, top) and the hypothalamus (left, bottom). Images of the same sections counterstained with cresyl violet are shown for comparison (right). Sections shown are from #249 (pineal gland) and #273 (hypothalamus). Scale bar, 1 mm. 3V, third ventricle; SON, supraoptic nucleus; ZT, Zeitgeber time.

Figure 4. Cell-specific Bsx expression in the adult rat pineal gland.

RNAscope in situ hybridization for detection of Bsx (red) and Aanat (orange) transcripts in coronal sections of the pineal gland of rats sacrificed at Zeitgeber time 18. Sections were also stained in DAPI for comparison. Arrow heads indicate the same cell photographed with different filter settings. Scale bars, 100 µm (left) and 20 µm (right).

Radiochemical in situ hybridization on sections from brains obtained throughout the day showed a significant 10-fold diurnal rhythm in Bsx mRNA levels of the pineal gland in 12L:12D (P<0.01) (Fig. 5A,C). A similar rhythmic expression was detected in DD (P<0.0001), showing that pineal Bsx expression is circadian in nature (Fig. 5B,C). Under both lighting conditions, pineal Bsx expression reached a peak in the middle of the night (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Rhythmic expression of Bsx in the adult rat pineal gland.

A, B) Radiochemical in situ hybridization for detection of Bsx transcripts in the pineal glands of rats sacrificed at the indicated time points under a 12h light:12h dark schedule (12L:12D) (A) and in constant darkness (DD) (B). Scale bars, 1 mm. C) Densitometric quantification of radiochemical in situ hybridization corresponding to A and B. One-way ANOVA detected significant effects of time on Bsx transcript levels in both 12L:12D (P<0.01) and DD (P<0.0001). Fold changes (ratios between highest and lowest measured transcript levels) were 10.0 ± 6.5 for Zeitgeber time (ZT) 15:ZT3 and 11.3 ± 1.2 for circadian time (CT) 15:CT6, while cosinor analysis estimated the times of peak expression at ZT18.8 ± 2.1 in 12L:12D and CT17.5 ± 2.0 in DD. Shaded areas indicate dark conditions; breaks in the light/dark bar indicate that sampling was performed separately for LD and DD. Values on the graph represent mean ± SEM; n=3, except for ZT3 (n=4), ZT12 (n=4), and ZT15 (n=2). CT, circadian time; ZT, Zeitgeber time.

Pineal Bsx expression is driven by sympathetic adrenergic signaling acting at the transcriptional level

The nocturnal expression of Bsx and previous large-scale RNA sequencing analyses indicate that pineal Bsx is regulated by the sympathetic adrenergic input to the gland via the second messenger cAMP17. The neural pathway connecting the suprachiasmatic nucleus with the pineal gland was lesioned by either decentralizing the SCG (SCGdcn), i.e. cutting the preganglionic fibers in the sympathetic trunk leading to the SCG, or removing the ganglia (SCGx). In situ hybridization on the pineal gland showed that these surgical procedures significantly affected pineal Bsx expression (P<0.0001). Bsx mRNA levels were significantly higher at ZT18 in control rats (P<0.05), while no differences in Bsx mRNA levels were detected between day and night in neither SCGx nor SCGdcn rats (P>0.05), showing that an intact neural pathway is necessary for maintaining daily changes in pineal Bsx expression (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Regulation of pineal Bsx expression by the sympathetic adrenergic input to the gland.

A) Radiochemical in situ hybridization for detection of Bsx transcripts in the pineal gland of rats with superior cervical ganglionectomy (SCGx), decentralized superior cervical ganglia (SCGdcn), and corresponding controls. Two-way ANOVA detected significant effects of both ZT (P<0.001) and surgical procedures (P<0.0001) on Bsx transcript levels. n=4, except for SCGdcn at ZT18, where n=3. Scale bar, 1 mm. B) Radiochemical in situ hybridization for detection of Bsx transcripts in the pineal gland of rats injected with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or isoprenaline (ISO) during daytime. PBS, n=5; ISO, n=7. Scale bar, 1 mm. C) Bsx transcript levels in rat pineal cell cultures treated with norepinephrine (NE) or dibutyryl-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (DBcAMP) for 6h or 12h as determined by qRT-PCR. Two-way ANOVA detected significant effects of both stimulation type and duration (P<0.0001) on Bsx transcript levels. n=4. D) Bsx transcript levels in rat pineal cell cultures treated with actinomycin and/or stimulated with DBcAMP as determined by qRT-PCR. Two-way ANOVA detected significant effects of both actinomycin-treatment and DBcAMP-stimulation (P<0.0001) on Bsx transcript levels. n=3. Values on the graphs represent mean ± SEM. P-values determined by Welch’s or Student’s t-tests with Bonferroni corrections (A, C, D) or uncorrected Welch’s t-test (B): ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001. ZT, Zeitgeber time.

To investigate if the Bsx rhythm in the pineal gland is driven by adrenergic signaling, rats were injected with isoprenaline during daytime, thus mimicking the nocturnal release of norepinephrine in the gland (Fig. 6B). Isoprenaline significantly increased Bsx mRNA levels (P<0.05), indicating that pineal Bsx expression is directly under the influence of adrenergic signaling (Fig. 6B).

To further delineate the regulatory roles of adrenergic stimulation and the second messenger cAMP, Bsx mRNA levels in pinealocyte cultures were assessed by use of qRT-PCR following stimulation with NE or DBcAMP (Fig. 6C). These treatments exerted significant effects on Bsx expression (P<0.0001); Bsx transcript levels were significantly increased in NE- and DBcAMP-treated cultures after both 6h (P<0.0001) and 12h of stimulation (NE, P<0.001; DBcAMP, P<0.01).

To clarify if cAMP-stimulation of Bsx expression occurs at the transcriptional level, the effect of DBcAMP on Bsx expression was analyzed in pinealocyte cultures pretreated with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (Fig. 6D). Actinomycin D significantly affected Bsx expression dynamics (P<0.0001) and the DBcAMP-induced increase of Bsx mRNA levels was not detected in actinomycin D-pretreated pinealocytes (P>0.05), indicating that upregulation of Bsx via cAMP requires de novo synthesis of Bsx mRNA.

Bsx is a negative regulator of the homeobox genes Pax4 and Otx2, but does not affect the expression of other important pineal homeobox genes or genes encoding melatonin-synthesizing enzymes

Since the pineal gland does not develop fully in Bsx knockouts14, we applied in vitro siRNA-mediated Bsx knockdown in pineal cell cultures to study the role of Bsx in the adult pineal gland. Bsx was knocked down in cultured cells treated with siRNA targeting Bsx (siBsx) and stimulated with NE to mimic the nocturnal situation in the gland (Fig. 7). The knockdown was verified by use of qRT-PCR: siBsx significantly reduced Bsx mRNA levels (P<0.0001) by approximately 80% (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. The effects of siRNA-mediated Bsx knockdown on expression of genes encoding melatonin-synthesizing enzymes and homeodomain proteins in cultured pineal cells.

Analyses of Bsx (A), Tph1 (B), Aanat (C), Asmt (D), Pax4 (E), Rax (F), Otx2 (G), and Crx (H) transcript levels in rat pineal cell cultures treated with non-targeting siRNA (siNT) or siRNA targeting Bsx (siBsx) and stimulated with norepinephrine (NE) for 6h or 12h; transcript levels determined by qRT-PCR. The knockdown of Bsx by siBsx corresponded to 83%, 85%, and 71% reductions at 0h, 6h, and 12h, respectively. Two-way ANOVA detected significant effects of NE on transcript levels of Bsx (P<0.0001), Tph1 (P<0.05), Aanat (P<0.0001), Rax (P<0.0001), Crx (P<0.0001), Pax4 (P<0.0001), and Otx2 (P<0.01), and significant effects of siRNA on transcript levels of Bsx (P<0.0001), Pax4 (P<0.0001), and Otx2 (P<0.01). Values on the graphs represent mean ± SEM, n=6. P-values determined by Welch’s or Student’s t-tests with Bonferroni corrections: ns, not significant; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

To investigate the possible role of Bsx in regulation of melatonin synthesis, transcript levels of the genes encoding the enzymes responsible for this process were analyzed. As expected, NE stimulation increased the levels of Aanat (P<0.0001)3, but significant effects of siBsx on expression of Tph1, Aanat or Asmt at specific time-points after NE-stimulation were not detectable (P>0.05) (Fig. 7B–D).

The possible role of Bsx in regulation of other pineal homeobox genes was investigated by determining the effect of Bsx knockdown on expression of the paired box 4 (Pax4), retinal and anterior neural fold (Rax), orthodenticle 2 (Otx2), and cone-rod (Crx) homeobox genes (Fig. 7E–H). NE stimulation exerted a significant effect on all four homeobox genes (Otx2, P<0.01; Pax4, Rax, Crx, P<0.0001) in agreement with their rhythmic nature in vivo4. Differences in transcript levels between siNT- and siBsx-treated pinealocyte cultures were not detectable for Rax and Crx (P>0.05) (Fig. 7F,H). However, siBsx-treatment exerted significant effects on Pax4 (P<0.0001) with increased levels at all three time points (0h and 6h, P<0.001; 12h, P<0.0001), suggesting that Bsx is a negative regulator of Pax4 (Fig. 7E). Knockdown of Bsx affected Otx2 positively (P<0.01), indicating that Bsx may also negatively regulate Otx2, but significantly higher levels of Otx2 transcripts were only detected after 12 h of NE stimulation (P<0.0001) (Fig. 7G).

RNA sequencing identifies Bsx as a regulator of the adult rat pineal transcriptome

The global effects of Bsx on the rat pineal transcriptome were investigated using RNA sequencing of pineal cell cultures treated with siBsx or siNT and stimulated with DBcAMP for 6h to mimic nighttime. A PCA plot showed separate clustering for the two treatments (Supporting Information, Fig. S1). The siBsx-mediated knockdown of Bsx was confirmed (P<0.0001, 79% decrease) (Fig. 8). Minor differences, though significant with the statistical approach used here, were detected for the genes encoding key pineal homeodomain proteins and melatonin pathway enzymes (P-values < 0.05); however, only Pax4 and Rax showed changes in relative expression greater than 25% (P<0.01; 143% and 39% increase in siBsx-cultures, respectively) (Fig. 8). After filtering, a total of 801 differentially expressed genes, 372 upregulated and 427 downregulated in siBsx-treated cultures, were included in a DAVID analysis. Examining output for the GOterm Biological Processes at level 5 revealed a significant overrepresentation of genes involved in five types of developmental processes (Bonferroni-corrected P-values < 0.01), reflecting the role of Bsx as a developmental regulator (Table 3; Supporting Information, Table S1).

Figure 8. The effects of siRNA-mediated Bsx knockdown on expression of genes encoding melatonin-synthesizing enzymes and homeodomain proteins in cultured pineal cells as determined by RNA sequencing.

Changes in expression of genes encoding homeodomain proteins and melatonin-synthesizing enzymes in pineal cell cultures treated with siRNA targeting Bsx (siBsx) and stimulated with DBcAMP for 6 hours as determined by RNA sequencing. Values on the Y-axis are given as percentagewise relative expression compared to controls treated with non-targeting siRNA (siNT). P-values determined by Wald tests with Benjamini-Hochberg corrections: *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Table 3. The effects of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Bsx on the rat pinealocyte transcriptome determined by RNA sequencing.

DAVID output for the GOterm Biological Processes at level 5 with significant overrepresentation in siBsx-treated pineal cell cultures compared to siNT-treated cultures as determined by RNA sequencing.

| Gene function | % of filtered genes mapped to gene function | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| Animal organ development | 26.34% | **** |

| Nervous system development | 17.60% | ** |

| Cell development | 17.47% | *** |

| Neuron development | 10.43% | *** |

| Sensory organ development | 6.65% | ** |

Bonferroni-corrected P-values below 0.01 were considered statistically significant

, P<0.0001

, P<0.001

, P<0.01.

Discussion

Current knowledge establishes a role of Bsx in development of the pineal gland in several vertebrate species13–16; in addition, genome-wide large-scale screening efforts suggest rhythmic expression of Bsx in the mature pineal gland of the rat17. The present study expands upon this knowledge by exploring persistent ontogenetic expression, cellular localization, regulation, and molecular role of Bsx in the rat pineal gland, as well as anatomical distribution of BSX transcripts in the human pineal gland.

Development of the pineal gland in mammals is guided by a number of homeobox gene-encoded transcription factors4. Bsx is required for proper development of the murine pineal gland along with Lhx9, Pax6, and Otx25,6,14,28, while other pineal homeobox genes, such as Rax, Crx, and Pax47–9, seem to exert their function at postnatal stages. Bsx and Otx27 fall into both categories by being continuously expressed from development into adulthood in the rat pineal gland. The essential role for Bsx in rodent pineal gland development represents a challenge in loss-of-function experiments on the mature pineal gland14. To circumvent the hypoplastic pineal gland of the Bsx knockout model, we here utilized an siRNA-based method for in vitro gene silencing. Although this approach does not fully attenuate Bsx expression levels, it represents an advantage over knockout models by allowing tissue-specific knockdown in pinealocytes from a melatonin-proficient mature gland.

By employing siRNA-mediated knockdown in cultured rat pinealocytes, we have previously shown that Otx2 and Crx are required for obtaining high expression of all three genes encoding the melatonin-synthesizing enzymes, namely Tph1, Aanat, and Asmt12, and studies in a conditional knockout mouse suggest that Rax controls expression of pineal Aanat11. However, in the current study we saw no effect on mRNA levels of the enzymes in the melatonin synthesis pathway following siRNA-mediated knockdown of Bsx in pinealocyte cultures. Therefore, as opposed to other pineal homeobox genes, there is no evidence that Bsx play a role as a central regulator of melatonin production in the adult, despite prominent nocturnal expression in melatonin-proficient pinealocytes. However, this does not exclude the possibility that it might act at early stages of development to irreversibly influence the expression of one or more of these genes.

On the other hand, in a search for targets among other pineal homeobox genes expressed in adults, we found Bsx to be a negative regulator of Pax4. As previously reported, homeobox genes and Aanat exhibit circadian expression profiles with a distinct sequential pattern in times of peak mRNA levels in the mature pineal gland, in the order of Pax4 (mid-to-late day), Rax (day-night transition), Otx2 (early-to-mid night), Crx (mid night), and Aanat (mid-to-late night)4. The role of Bsx as a negative regulator of Pax4 presented in this study fits into this model, as the rhythm of Bsx expression with a peak in the middle of the night is anti-phasic to that of Pax4, which peaks during the day. Similarly, previous studies have described mutual regulation of Crx and Otx2, as knockdown of Otx2 decreased Crx mRNA levels, while knockdown of Crx resulted in increased mRNA levels of Otx25,12. In our RNAseq analyses, Bsx knockdown influenced a number of pineal homeobox genes, while, in addition to Pax4, qPCR analyses only confirmed an effect on Otx2 after 12h of NE stimulation. These apparent discrepancies probably reflect different statistical approaches and cutoff criteria. The fact that homeobox genes, including both Bsx itself and its downstream targets, would normally guide development of various cell types is reflected in the results of the DAVID analysis of our RNAseq data indicating that Bsx influences a number of developmental processes. However, in addition to regulation of developmental processes and melatonin synthesis, our data suggest the presence of an internal regulatory interplay between pineal homeobox genes, which might also explain the differences in circadian expression profiles despite the genes being under control of the same adrenergic input to the gland.

Our data show that Bsx expression is circadian in nature and driven by norepinephrine released from sympathetic nerve endings acting via cAMP as a second messenger to induce nocturnal transcription of Bsx. The same signaling mechanism drives the nocturnal increase in Aanat mRNA levels and other transcripts in the rat pineal transcriptome1,17,29, including pineal homeobox genes as described above. However, unlike other pineal homeobox genes governed by the same regulatory mechanisms, Bsx expression was not detected in the retina. Otx2, Crx, Rax, Pax6, and Pax4 are highly expressed in both tissues at various developmental stages in the rat9,30,31, reflecting the close evolutionary relationship between the pinealocyte and the retinal photoreceptor cell32. Bsx may be a determining factor required for obtaining and maintaining the pinealocyte phenotype; the underlying transcriptional network may otherwise be similar to that of the retinal photoreceptor. This would imply mammalian Bsx to be a potential determining factor for pineal cell fate during development, as has been suggested in studies on non-mammalian vertebrates, including Xenopus and zebrafish15,16,33. In contrast to mammals, the pineal gland of non-mammalian vertebrates is a photoreceptive organ with pineal photoreceptors sharing common ancestry with the mammalian pinealocyte34,35. In both Xenopus and zebrafish, Bsx homologs were shown to control specification of photoreceptive pinealocytes15,16,33,35. Expression of BSX in the human pineal gland, as reported here, is consistent with a view of a conserved role for pineal Bsx across species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the Lundbeck Foundation (grant number R249-2017-931 to MBC and MFR), the Independent Research Fund Denmark (grant number 8020-00037B to MFR), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant numbers NNF15OC0015988 and NNF17OC0026938 to MFR), and the Carlsberg Foundation (grant numbers CF15-0515 and CF17-0070 to MFR). We wish to thank Rikke Lundorf for expert histological assistance and the Molecular Genomics Core (NICHD, NIH) for technical support on RNA sequencing. We further wish to thank Prof. Éva Dobolyine Renner and Prof. Miklós Palkovits, Human Brain Tissue Bank, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary, for providing human brain tissue, supported by NAP 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00002.

Abbreviations

- Aanat

arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase

- Actb

actin beta

- Asmt

acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase

- Bsx

brain-specific homeobox gene

- Crx

cone-rod homeobox

- CT

circadian time

- DBcAMP

dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- DD

constant darkness

- E

embryonic day

- 12L:12D

12 h light:12 h dark schedule

- Gapdh

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- NE

norepinephrine

- Otx2

orthodenticle homeobox 2

- P

postnatal day

- Pax4

paired box 4

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- Rax

retinal and anterior neural fold homeobox

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- SCGdcn

decentralization of the superior cervical ganglia

- SCGx

superior cervical ganglionectomy

- Tph1

tryptophan hydroxylase 1

- ZT

Zeitgeber time

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Klein DC. Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase: “the Timezyme”. J Biol Chem 2007;282(7):4233–4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Møller M, Baeres FM. The anatomy and innervation of the mammalian pineal gland. Cell Tissue Res 2002;309(1):139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roseboom PH, Coon SL, Baler R, McCune SK, Weller JL, Klein DC. Melatonin synthesis: analysis of the more than 150-fold nocturnal increase in serotonin N-acetyltransferase messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat pineal gland. Endocrinology. 1996;137(7):3033–3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rath MF, Rohde K, Klein DC, Møller M. Homeobox genes in the rodent pineal gland: roles in development and phenotype maintenance. Neurochem Res 2013;38(6):1100–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishida A, Furukawa A, Koike C, et al. Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nat Neurosci 2003;6(12):1255–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamazaki F, Møller M, Fu C, et al. The Lhx9 homeobox gene controls pineal gland development and prevents postnatal hydrocephalus. Brain Struct Funct 2015;220(3):1497–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rath MF, Munoz E, Ganguly S, et al. Expression of the Otx2 homeobox gene in the developing mammalian brain: embryonic and adult expression in the pineal gland. J Neurochem 2006;97(2):556–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rath MF, Bailey MJ, Kim JS, et al. Developmental and diurnal dynamics of Pax4 expression in the mammalian pineal gland: nocturnal down-regulation is mediated by adrenergic-cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate signaling. Endocrinology. 2009;150(2):803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohde K, Klein DC, Møller M, Rath MF. Rax : developmental and daily expression patterns in the rat pineal gland and retina. J Neurochem 2011;118(6):999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohde K, Rovsing L, Ho AK, Møller M, Rath MF. Circadian dynamics of the cone-rod homeobox (CRX) transcription factor in the rat pineal gland and its role in regulation of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT). Endocrinology. 2014;155(8):2966–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohde K, Bering T, Furukawa T, Rath MF. A modulatory role of the Rax homeobox gene in mature pineal gland function: Investigating the photoneuroendocrine circadian system of a Rax conditional knockout mouse. J Neurochem 2017;143(1):100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohde K, Hertz H, Rath MF. Homeobox genes in melatonin-producing pinealocytes: Otx2 and Crx act to promote hormone synthesis in the mature rat pineal gland. J Pineal Res 2019:e12567. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cremona M, Colombo E, Andreazzoli M, Cossu G, Broccoli V. Bsx, an evolutionary conserved Brain Specific homeoboX gene expressed in the septum, epiphysis, mammillary bodies and arcuate nucleus. Gene Expr Patterns 2004;4(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McArthur T, Ohtoshi A. A brain-specific homeobox gene, Bsx, is essential for proper postnatal growth and nursing. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27(14):5120–5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Autilia S, Broccoli V, Barsacchi G, Andreazzoli M. Xenopus Bsx links daily cell cycle rhythms and pineal photoreceptor fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(14):6352–6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schredelseker T, Driever W. Bsx controls pineal complex development. Development. 2018;145(13). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartley SW, Coon SL, Savastano LE, et al. Neurotranscriptomics: The Effects of Neonatal Stimulus Deprivation on the Rat Pineal Transcriptome. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savastano LE, Castro AE, Fitt MR, Rath MF, Romeo HE, Munoz EM. A standardized surgical technique for rat superior cervical ganglionectomy. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;192(1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klitten LL, Rath MF, Coon SL, Kim JS, Klein DC, Møller M. Localization and regulation of dopamine receptor D4 expression in the adult and developing rat retina. Exp Eye Res 2008;87(5):471–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, Flanagan J, Su N, et al. RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J Mol Diagn 2012;14(1):22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4(1):44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu HY, Ohtoshi A. Cloning and functional analysis of hypothalamic homeobox gene Bsx1a and its isoform, Bsx1b. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27(10):3743–3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakkou M, Wiedmer P, Anlag K, et al. A role for brain-specific homeobox factor Bsx in the control of hyperphagia and locomotory behavior. Cell Metab 2007;5(6):450–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nogueiras R, Lopez M, Lage R, et al. Bsx, a novel hypothalamic factor linking feeding with locomotor activity, is regulated by energy availability. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):3009–3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Estivill-Torrus G, Vitalis T, Fernandez-Llebrez P, Price DJ. The transcription factor Pax6 is required for development of the diencephalic dorsal midline secretory radial glia that form the subcommissural organ. Mech Dev 2001;109(2):215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bustos DM, Bailey MJ, Sugden D, et al. Global daily dynamics of the pineal transcriptome. Cell Tissue Res 2011;344(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rath MF, Morin F, Shi Q, Klein DC, Møller M. Ontogenetic expression of the Otx2 and Crx homeobox genes in the retina of the rat. Exp Eye Res 2007;85(1):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rath MF, Bailey MJ, Kim JS, Coon SL, Klein DC, Møller M. Developmental and daily expression of the Pax4 and Pax6 homeobox genes in the rat retina: localization of Pax4 in photoreceptor cells. J Neurochem 2009;108(1):285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein DC. The 2004 Aschoff/Pittendrigh lecture: Theory of the origin of the pineal gland--a tale of conflict and resolution. J Biol Rhythms 2004;19(4):264–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mano H, Asaoka Y, Kojima D, Fukada Y. Brain-specific homeobox Bsx specifies identity of pineal gland between serially homologous photoreceptive organs in zebrafish. Commun Biol 2019;2:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekström P, Meissl H. Evolution of photosensory pineal organs in new light: the fate of neuroendocrine photoreceptors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2003;358(1438):1679–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mano H, Fukada Y. A median third eye: pineal gland retraces evolution of vertebrate photoreceptive organs. Photochem Photobiol 2007;83(1):11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.