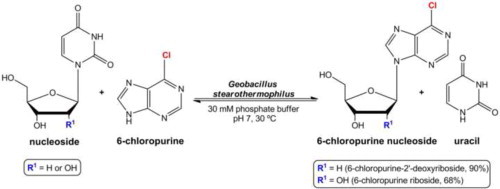

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Geobacillus stearothermophilus, Nucleoside analogues, Green chemistry, Entrapment immobilization

Abstract

This work describes the application of thermophilic microorganisms for obtaining 6-halogenated purine nucleosides. Biosynthesis of 6-chloropurine-2′-deoxyriboside and 6-chloropurine riboside was achieved by Geobacillus stearothermophilus CECT 43 with a conversion of 90% and 68%, respectively. Furthermore, the selected microorganism was satisfactorily stabilized by immobilization in an agarose matrix. This biocatalyst can be reused at least 70 times without significant loss of activity, obtaining 379 mg/L of 6-chloropurine-2′-deoxyriboside. The obtained compounds can be used as antiviral agents.

It is known that 6-halogenated purine nucleosides and their derivatives play an important role in antiviral therapies. The activity of 6-chloropurine-2′-deoxyriboside and 6-chloropurine riboside against hepatitis C virus (HCV)1 and SARS coronavirus (SARS Co-V)2 has already been demonstrated. Moreover, the antitumoral activity of 6-chloropurine riboside has been assayed on leukemic cells.3

Nucleoside analogues are principally synthesized by chemical methods. Such methods require organic solvents, multiple reaction steps and the removal of protective groups, yielding undesirable racemic mixtures,4 decreasing conversion and affecting product purification. However, biocatalysis emerged as an alternative to these drawbacks owing to its high catalytic efficiency, inherent selectivity and simple downstream processing. Biosynthesis of 6-modified purine nucleosides by transglycosylation using microorganisms was previously reported.5 These reactions can be performed stereo-selectively by nucleoside phosphorylase (NP) enzymes.6

Thermophilic microorganisms are a source of enzymes with extreme stability.7 The application of these microorganisms as biocatalysts is attractive for industrial bioprocesses.

Microorganism stabilization by immobilization techniques is a good method to carry out biotransformations because it allows high operational stability, easy upstream separation and bioprocess scale-up feasibility. Cell entrapment techniques are the most widely used for whole cell immobilization.8

The present work describes an efficient one-pot biosynthesis of 6-halogenated purine nucleosides using a smooth, cheap and environmentally friendly methodology. These compounds are used as antiviral compounds, prodrugs or antileukemic agents.

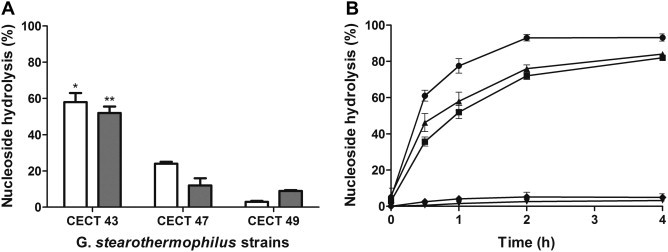

The ability of Geobacillus stearothermophilus to hydrolyze uridine (Urd) and thymidine (dThd) was evaluated in order to identify the optimal strain for 6-halogenated purine nucleoside biosynthesis (Fig. 1 A). G. stearothermophilus CECT 43 showed the highest activity for both nucleosides tested. Hydrolysis was quantitatively evaluated by HPLC analysis, which was performed on Nucleodur 100-5 C18 column (5 μm, 125 mm × 5 mm) using a UV detector (254 nm). The column was operated using isocratic mobile phase water/methanol (90:10, v/v) at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min.

Figure 1.

Selection of G. stearothermophilus strain for 6-halogenated purine nucleosides biosynthesis. Hydrolysis reactions were carried out three times using 1 × 1010 CFU (colony forming units), 2 mM nucleoside in 0.5 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7) at 55 °C and 200 rpm. The reaction medium without microorganisms was used as control. (A) Hydrolysis of dThd (white) and Urd (gray) using different G. stearothermophilus strains at 1 h of reaction. Significant differences when dThd (∗P <0.001) and Urd (∗∗P <0.001) were used. (B) Hydrolysis of different sugar donors: dThd (triangle), Urd (square), dUrd (circle), araUra (inverted triangle) and ddUrd (rhombus) using G. stearothermophilus CECT 43. Thermophilic microorganisms were kindly supplied by the ‘Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo (CECT)’, Universidad de Valencia (Spain).

When hydrolysis of other sugar donors was evaluated (Fig. 1B), G. stearothermophilus CECT 43 was able to hydrolyze 93% of 2′-deoxyuridine (dUrd) after 2 h of reaction. On the other hand, no significant activity was detected when uracil 1-β-d-arabinofuranoside (araUra) or 2′,3′-dideoxyuridine (ddUrd) were evaluated at short reaction times (2 h). Therefore, subsequent assays were performed using dUrd as nucleoside sugar donor.

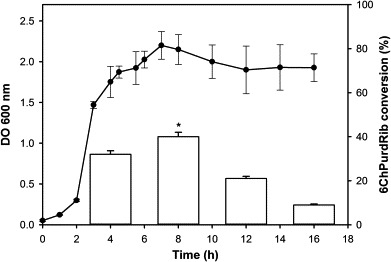

It is known that G. stearothermophilus has NPs.9 These enzymes catalyze reversible phosphorolytic cleavage of N-glycosidic bonds of nucleosides to form a free base and its respective activated pentose moiety, which is then coupled to the desired modified base to yield a nucleoside analogue. These enzymes are involved in a nucleoside salvage pathway and their expression during different growth phases may vary.6 For this reason, 6-chloropurine-2′-deoxyriboside (6ChPurdRib) biosynthesis was evaluated at different stages of microorganism growth (Fig. 2 ). All reactions were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC as described above and product characterization was performed by MS-HPLC using a LCQ-DECAXP4 Thermo Finnigan Spectrometer with the Electron Spray Ionization method (ESI) and one ion trap detector. The experimental conditions were: voltage source 5.0 kV, capillary voltage 14 V, gas flow rate (35 arbitrary units), temperature 200 °C. For 6ChPurdRib (M+: 272.6) biosynthesis, an isocratic water/methanol (0.1% acetic acid) (85:15 v/v) mobile phase was used at a flow rate of 200 μL/min.

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of 6ChPurdRib at different growth stages. G. stearothermophilus was grown at 55 °C in media contained 10 g/L meat peptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl and 4 g/L glucose at pH 7, and 1 × 1010 CFU were collected at several times. Biosynthesis was carried out during 2 h of reaction in 0.5 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7) at 55 °C and 200 rpm using 2 mM 6ChPur and 6 mM dUrd as substrates. All reactions were performed three times and conversion was calculated as: (mmol product/mmol limiting reagent) ∗ 100. Significant differences respect to the other growth times: ∗P <0.001.

The best conversion was achieved with cultures at early stationary phase (8 h). Therefore, for the following assays, we grew G. stearothermophilus strain CECT43 to this phase.

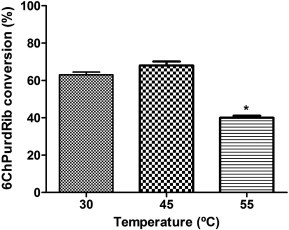

Previously, we had shown that temperature influences enzyme activity, thus its effect was evaluated on the conversion reaction.10 Therefore, 6ChPurdRib biosynthesis was performed at 30, 45 and 55 °C (Fig. 3 ). The best conversion values were obtained at temperatures lower than the optimum temperature for growth of the microorganism. Based on the obtained results, we have observed hydrolase activity on the chlorine atom when the reaction was carried out at high temperatures, decreasing 6ChPurdRib conversion. As similar yields were obtained at 30 and 45 °C and due to operational facility requirements, the selected temperature for subsequent trials was 30 °C.

Figure 3.

Biosynthesis of 6ChPurdRib at different temperatures. Reactions were carried out three times in 0.5 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7) during 2 h using 1 × 1010 CFU, 2 mM 6ChPur and 6 mM dUrd at 200 rpm. Conversion was calculated as: (mmol product/mmol limiting reagent) ∗ 100. Significant differences respect to 30 and 45 °C: ∗P <0.001.

Different reaction variables were tested in order to optimize other reaction parameters for obtaining 6-halogenated purine nucleosides. The importance of the presence of phosphate in the reaction for nucleoside phosphorolysis by NP has been previously reported.11 Preliminary tests were performed to optimize different phosphate concentrations (20, 30 and 40 mM), pH values (5, 6, 7 and 8) and stirring speed (100, 200 and 300 rpm). No significant differences were observed among several parameters (see Supplementary data). Therefore, we decided to use 30 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7 and 200 rpm as standard conditions.

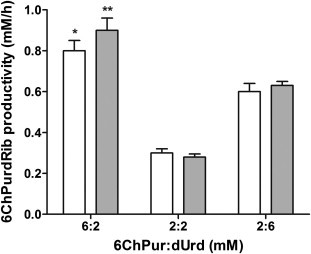

It has been widely reported that transglycosylation reactions are reversible12 and it was shown that an excess of substrates improves transglycosylation. We studied 6ChPurdRib biosynthesis in the presence of an excess of 6-halogenated base, an excess of nucleoside donor (dUrd) or equal molar quantities (Fig. 4 ). Lower yields of 6ChPurdRib productivity were obtained when equimolar quantities of substrates were used. Productivity was 0.63 mM/h when 2:6 mM ratio (6ChPur/dUrd) was evaluated. However, when an excess of 6-halogenated base was tested (6:2 mM ratio), 6ChPurdRib productivity was increased significantly (0.9 mM/h). This difference could be due to an excess of 6ChPur that shifts the equilibrium favoring 6ChPurdRib formation, since the modified base competes more effectively against natural purines within microorganisms.

Figure 4.

6ChPurdRib productivity using different initial molar ratios of substrates. Reactions were performed during 1 h (white) and 2 h (gray) with 1 × 1010 CFU at 30 °C in potassium phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7) and 200 rpm using 6ChPur and dUrd at different ratios (base/2′-deoxyriboside). All reactions were performed three times and productivity was calculated relative to the limiting reagent concentration. Significant differences at 1 h (∗P <0.001) or 2 h (∗∗P <0.001) of reaction respect to other ratios.

Once the reaction parameters were optimized, we evaluated the biosynthesis of different 6-halogenated purine ribo- and 2′-deoxyribosides using 6-chloro, 6-bromo and 6-iodopurine as starter purine bases and dUrd or Urd as sugar donors. Quantitative analysis was carried out by HPLC and product identification was performed by MS-HPLC under the above mentioned conditions. 6ChPurRib (M+: 287.5), 6IPurdRib (M+: 327.1), 6IPurRib (M+: 343.0), 6BrPurdRib (M+: 316.2) and 6BrPurRib (M+: 332.2). We were able to obtain acceptable productivity for subsequent bioprocess scale-up. However, a higher conversion was obtained when dUrd was used as sugar donor instead Urd, because 2′-deoxyriboside hydrolysis was greater. G. stearothermophilus strain CECT43 was able to synthesize 6-halogenated purine ribosides and 2′-deoxyribosides with a conversion greater than 50% in all cases (Table 1 ). The presence of two PNPs (PNPI and PNPII) in G. stearothermophilus could account for the acceptance of different purine bases.9 In conclusion, we have been able to prepare a broad spectrum of different 6-halogenated purine nucleoside analogues reaching significant productivities.

Table 1.

Biosynthesis of 6-halogenated purine nucleosides using G. stearothermophilus CECT 43 as biocatalyst

| Sugar donor | 6-Halogenated purine base | Reaction timea (h) | Conversionb (%) | Productivity (mM/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dUrd | 6ChPur | 2 | 90 | 0.90 |

| Urd | 6ChPur | 8 | 68 | 0.17 |

| dUrd | 6BrPur | 4 | 60 | 0.30 |

| Urd | 6BrPur | 8 | 50 | 0.13 |

| dUrd | 6IPur | 24 | 85 | 0.07 |

| Urd | 6IPur | 8 | 65 | 0.16 |

Reactions were performed at least three times with 1 × 1010 CFU at 30 °C in potassium phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7) and 200 rpm using 6 mM base/2 mM nucleoside ratio. 6ChPur: 6-chloropurine, 6IPur: 6-iodopurine and 6BrPur: 6-bromopurine.

The best times of reaction are shown.

Conversion (%) = .

Entrapment techniques are widely used for microorganism stabilization and allow reuse of biocatalyst. Different agarose (2%, 3%, 4% and 5%) and polyacrylamide (15%, 20% and 25%) concentrations were assayed for G. stearothermophilus immobilization as previously described by Rivero and col.13 The minimum matrix percentage for preventing microorganism release into the reaction medium was assessed, being 4% and 25% the optimum percentages for agarose and polyacrylamide immobilization, respectively. This thermophilic microorganism was successfully immobilized in agarose and polyacrylamide, obtaining 70% (at 6 h) and 61% (at 24 h) of 6ChPurdRib conversion, respectively. It was observed that the immobilized biocatalysts required longer time than free microorganisms to reach successful conversion values and it is well known that this difference is related to diffusion restrictions of these matrices.14 Finally, an agarose matrix was selected for subsequent tests.

G. stearothermophilus immobilized in agarose was stable for more than 6 months in storage conditions (4 °C) and could be reused at least 70 times without significant loss of activity (about 90% retained activity) reaching 379 mg/L of 6ChPurdRib while free microorganisms were stable at 4 °C for 10 days and lost their activity (less than 50% of initial activity) before 12 reuses (see Supplementary data).

We selected this biocatalyst to perform a preliminary test for bioprocess scale-up. These trials were conducted in a 10 ml batch reactor in the conditions previously optimized and the results were similar to those obtained at microscale.

Currently, environmental factor (E-factor) values to produce these compounds by pharmaceutical companies vary from 25 to 100.15 However, the use of safe microorganisms, the characteristics of the matrix and the simple recovery of excess substrates favor E-factor decrease more than 10-fold.

In this report, a new green bioprocess for 6-halogenated purine nucleosides production has been described by direct transglycosylation using G. stearothermophilus CETC 43 immobilized in an agarose matrix. This biocatalyst meets the requirements of high activity, stability and short reaction times needed for low cost production in a future preparative application using an environmentally friendly methodology.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica and Universidad Nacional de Quilmes. J A T, J E S and M E L are research members at CONICET; C W R and E C D are CONICET fellows, Argentina.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.045.

Supplementary data

References and notes

- 1.Ikejiri M., Ohshima T., Kato K., Toyama M., Murata T., Shimotohno K., Maruyama T. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. (Oxf). 2007:439. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrm220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikejiri M., Saijo M., Morikawa S., Fukushi S., Mizutani T., Kurane I., Maruyama T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:2470. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pankiewicz K.W., Goldstein B.M. In: Society A.C., editor. Vol. 839. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2003. p. 1. (ACS Symposium Series). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narayanasamy J., Pullagurla M.R., Sharon A., Wang J., Schinazi R.F., Chu C.K. Antiviral Res. 2007;75:198. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trelles J.A., Valino A.L., Runza V., Lewkowicz E.S., Iribarren A.M. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005;27:759. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-5628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bzowska A., Kulikowska E., Shugar D. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;88:349. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almendros M., Berenguer J., Sinisterra J.V. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:3128. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07605-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trelles J.A., Fernández-Lucas J., Condezo L.A., Sinisterra J.V. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2004;30:219. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamamoto T., Okuyama K., Noguchi T., Midorikawa Y. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997;61:272. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britos C.N., Cappa V.A., Rivero C.W., Sambeth J.E., Lozano M.E., Trelles J.A. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2012;79:49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utagawa C.Y., Sugayama S.M., Ribeiro E.M., Bertola D.R., Baba E.R., Burin M.G., Lewis E., Coelho H.C., Fensom A.H., Marques-Dias M.J., Gonzales C.H., Kim C.A., Giugliani R. Clin. Genet. 1999;55:386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pugmire M.J., Ealick S.E. Biochem J. 2002;361:1. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivero C.W., Britos C.N., Lozano M.E., Sinisterra J.V., Trelles J.A. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012;331:31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischer W., Kasche V. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:326. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheldon R. Chem. Commun. 2008:3352. doi: 10.1039/b803584a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.