Letter to the Editor

We read with interest the recent systematic review of Momattin et al. [1], which clearly reflects that although there have been concerns about emerging pathogenic coronaviruses, still there is a lack of enough research on many of their clinical, epidemiological, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Then, we would like to discuss how much has been investigated about coronaviruses (Cov), based on a bibliometric analysis in three bibliographic databases.

Coronaviruses cause respiratory and intestinal infections in animals and humans. They were not considered to be highly pathogenic to humans until the outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 and 2003 in Guangdong province, China; 10 years later with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Middle Eastern countries; and more recently in December 2019–January 2020 of a novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The coronaviruses that circulated before that time in humans mostly caused mild infections in immunocompetent people [2].

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) held its annual review of the Blueprint list of priority diseases, where coronaviruses were considered and included. These diseases, given their potential to cause public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC) and the absence of efficacious drugs and vaccines, are considered to need accelerated research and development [3].

We conducted a bibliometric analysis using available information from major biomedical journals-indexing databases in order to assess the current state of CoV-related literature worldwide. We used Science Citation Index (SCI), Scopus, and PubMed. Our search strategy involved collected data in indexed articles from the databases using the term “Coronavirus” as main operator, from January 1951–January 2020.

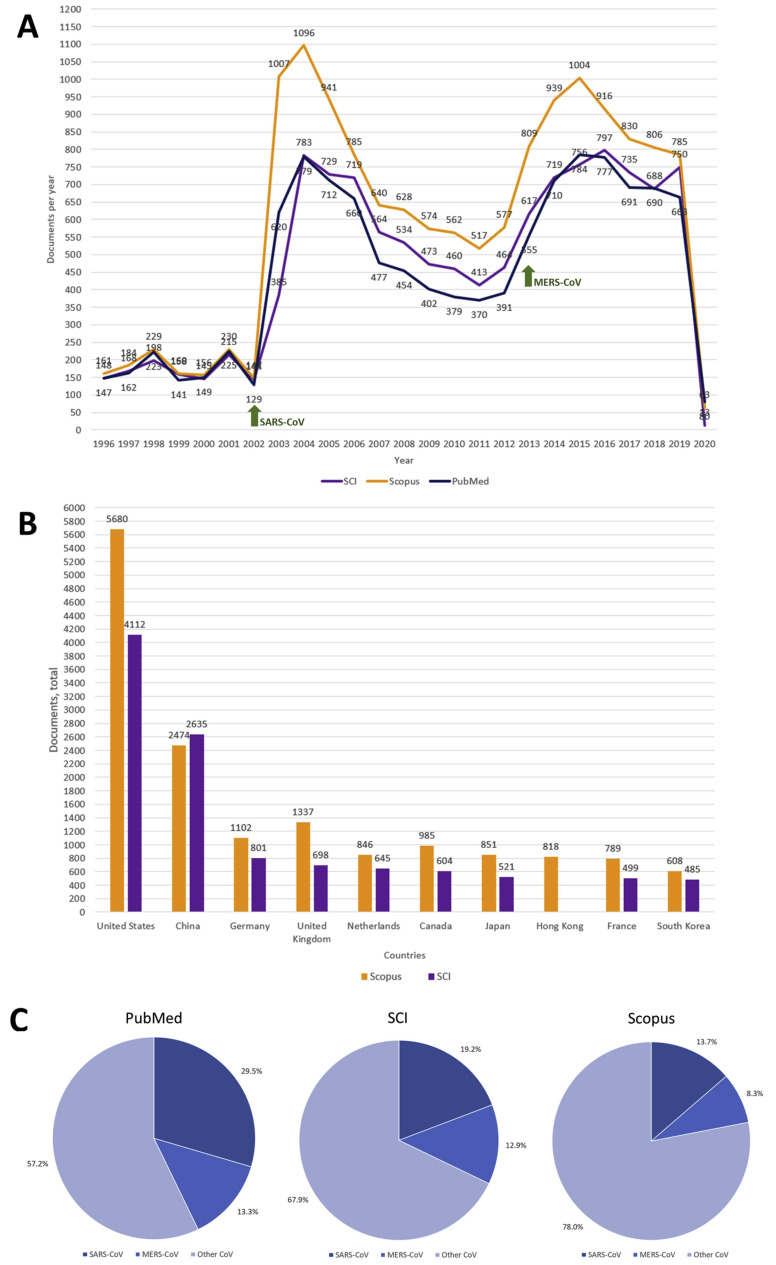

The Scopus search identified 18,158 articles (31.3% from USA, China 13.6% and United Kingdom 7.4%) followed by PubMed with 14,455 (20.1% USA, China 18.6% and Germany 4.2%), and SCI with 11,775 articles (34.9% from USA, 22.4% China and 6.8% Germany) (Fig. 1 ). In addition, 75.0%, 71.4% and 91.2% of the articles respectively were published after January 2002 (Fig. 1). From the total, 13.7%, 29.5%, 19.2%, respectively corresponded to SARS-CoV, and 8.3%, 13.3% and 12.9% to MERS-CoV, in such databases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scientific production on CoV. A. Trends in time, January 1996–January 2020 (SCI, Scopus and PubMed). B. Top ten countries in number of CoV-publications (SCI and Scopus). C. Distribution by different CoV research (SCI, Scopus and PubMed).

The results of this study show that USA and China have primary roles in CoV research, with USA leading the scientific production with nearly a third of the articles (Fig. 1). From the directly affected countries only China has significant article production with 22% of the total articles from SCI. In Asia, Hong Kong and South Korea are among the top ten, and they have been also affected by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [4,5]. In the case of countries in the Middle East, affected by MERS-CoV, such as Saudi Arabia, this area only contributed 3.6% of the publications in SCI and 2.5% at Scopus. With more than 7700 cases and 170 deaths, up to Jan. 30th, 2020, in 20 countries (14 of which are in Asia), research from Asia can be expected to increase significantly due to the current spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak [6], but also from countries in other continents, especially where already cases have been confirmed, as is the case of Australia (7), USA (5), Canada (3), France (5), Germany (4) and Finland (1), among others.

There are still no licensed vaccines for the prevention of any CoV and the treatment options are limited. As Momattin et al., indicated, there are a few promising therapeutic agents on the horizon for infections such as MERS-CoV, including the combination of lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon-beta-1β, and ribavirin and interferon [1]. Thus, most preventive measures are aimed to reduce the risk of infection. However, it must be noted that the 2019-2020 epidemic has set an unprecedented milestone in virology research by the way open science is tackling with exceptional speediness this outbreak. The availability of genome sequences, phylogenetic tracing analysis, and development of predictive models to better understand the biology of this virus has been generated almost in real-time, allowing a more rapid monitoring and response when compared to previous coronavirus outbreaks.

In conclusion, it is time to translate research findings into more effective measures, as with other priority diseases [7], such as a vaccine or effective therapeutic options, aimed at controlling viruses with clear epidemic potential, and to prioritize those interventions, to reduce and control the negative impact of diseases such as those caused by CoV, including the new emerging 2019-nCoV.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

D. Katterine Bonilla-Aldana: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Keidenis Quintero-Rada: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Juan Pablo Montoya-Posada: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Sebastian Ramírez-Ocampo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Alberto Paniz-Mondolfi: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Ali A. Rabaan: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Ranjit Sah: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Alfonso J. Rodríguez-Morales: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Methodology.

Declaration of competing interest

Alfonso J. Rodríguez-Morales attended as Expert Participant in The 2018 Annual Review of the WHO R&D Blueprint Priority List of Diseases, WHO HQ Avenue Appia 20, 1211 Geneva, 6th and 7th February 2018.

Footnotes

Contents were presented in part at the IV Latin American Congress of Virology and VIII Colombian Symposium of Virology, Bogota, Colombia, October 2–4, 2019, Oral Presentation.

References

- 1.Momattin H., Al-Ali A.Y., Al-Tawfiq J.A. A systematic review of therapeutic agents for the treatment of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Trav Med Infect Dis. 2019;30:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization List of Blueprint priority diseases. 2018. https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-diseases-for-research-and-development-in-emergency-contexts URL:

- 4.Leung G.M., Chung P.H., Tsang T., Lim W., Chan S.K., Chau P. SARS-CoV antibody prevalence in all Hong Kong patient contacts. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1653–1656. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan A., Farooqui A., Guan Y., Kelvin D.J. Lessons to learn from MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:543–546. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med. 2019 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Ramirez-Jaramillo V., Patino-Barbosa A.M., Bedoya-Arias H.A., Henao-SanMartin V., Murillo-Garcia D.R. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome - a bibliometric analysis of an emerging priority disease. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2018;23:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]