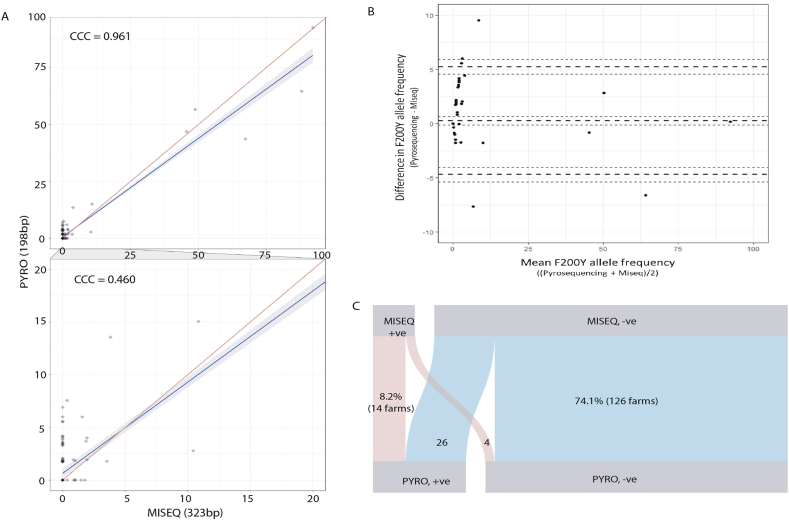

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the two different assays, pyrosequencing populations of individual egg/larvae and deep amplicon sequencing of bulk egg/larval DNA preparations to estimate frequency of resistant mutations in the N. battus β-tubulin isotype-1 gene.

Panel A. Scatter-plot of frequencies of resistant mutation at codon 200 generated from deep amplicon sequencing and pyrosequencing. Frequencies generated from sequencing on the x-axis and frequencies generated from pyrosequencing on the y-axis. Lin's Agreement analysis shows (0.961) that overall there is very little difference between the results generated from the two different assays except at the lower frequencies (<20%) when Lins' Agreement estimate drops to 0.460.

Panel B. Bland-Altman plot comparing F200Y allele frequency results obtained from pyrosequencing vs. deep amplicon sequencing. The mean F200Y allele frequency (x-axis) was plotted against the difference in F200Y allele frequency between the two technologies (y-axis) to explore the variation observed. The dashed lines represent the mean difference and standard deviations with the respective 95% confidence intervals of each indicated by dotted lines.

Panel C. Parallel-sets plot displaying the relative proportions of samples that are either positive i.e. the resistant mutation (200Y) is present on a farm or negative i.e. the resistant mutation is absent on that farm, at a threshold of 1%. The cross-over regions represent the relative proportion of samples that disagree between the assays and were categorised as suspected resistant farms (where one technology identified the F200Y mutation and the other did not). Suspect resistant alleles were more commonly identified by pyrosequencing than deep sequencing.