Abstract

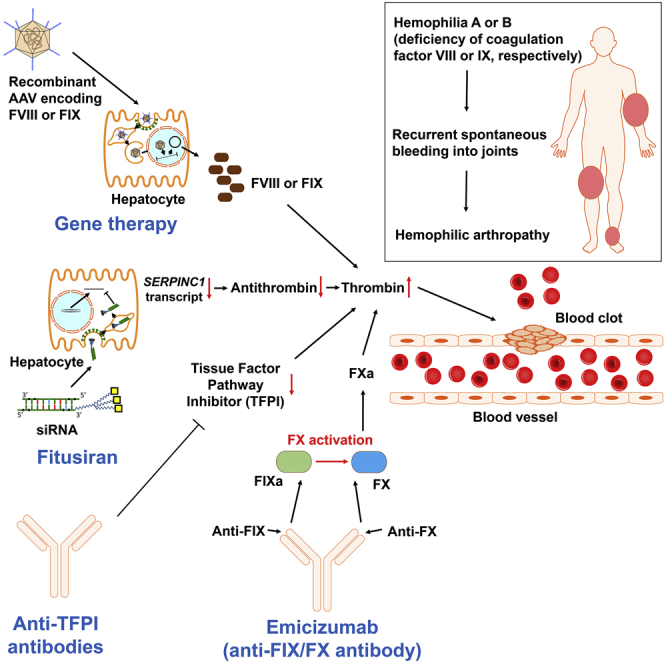

For decades, the monogenetic bleeding disorders hemophilia A and B (coagulation factor VIII and IX deficiency) have been treated with systemic protein replacement therapy. Now, diverse molecular medicines, ranging from antibody to gene to RNA therapy, are transforming treatment. Traditional replacement therapy requires twice to thrice weekly intravenous infusions of factor. While extended half-life products may reduce the frequency of injections, patients continue to face a lifelong burden of the therapy, suboptimal protection from bleeding and joint damage, and potential development of neutralizing anti-drug antibodies (inhibitors) that require less efficacious bypassing agents and further reduce quality of life. Novel non-replacement and gene therapies aim to address these remaining issues. A recently approved factor VIII-mimetic antibody accomplishes hemostatic correction in patients both with and without inhibitors. Antibodies against tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and antithrombin-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) target natural anticoagulant pathways to rebalance hemostasis. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy provides lasting clotting factor replacement and can also be used to induce immune tolerance. Multiple gene-editing techniques are under clinical or preclinical investigation. Here, we provide a comprehensive overview of these approaches, explain how they differ from standard therapies, and predict how the hemophilia treatment landscape will be reshaped.

Graphical Abstract

Hemophilia is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by mutations in factor VIII or IX and that is traditionally treated by intravenous protein replacement therapy. Butterfield et al. review how molecular therapies are dramatically transforming treatment through development of gene, monoclonal/bispecific antibody, and siRNA therapy.

Introduction

Therapy for hemophilia is being completely transformed by diverse, disruptive molecular therapies. Congenital hemophilia A and B are X-linked bleeding disorders caused by mutations of the F8 gene (one in 5,000 male births) or F9 gene (one in 30,000 male births), which lead to deficiencies of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) or IX (FIX), respectively.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 While deficiencies of other clotting factors exist, one of which (FXI deficiency) has been called hemophilia C, they show different clinical pictures.1,6 Hemophilia is characterized by painful and often spontaneous hemorrhages into joints and soft tissues that are life-threatening if intracranial, gastrointestinal, or in the neck/throat.2 Hemarthrosis accounts for 70%–80% of all bleeding episodes, and leads to hemophilic arthropathy.2,7, 8, 9 FVIII or FIX level (normal range is 50–150 IU/dL) typically correlates with bleeding severity: <1 IU/dL of normal is classified as severe hemophilia, 1–5 IU/dL as moderate, and 5–50 IU/dL as mild.2 The treatment of choice for management of acute bleeding is a recombinant or plasma-derived concentrate of FVIII or FIX.2 Those with severe hemophilia (approximately 45% of patients)10 require prophylactic replacement therapy to maintain trough FVIII or FIX levels of at least 1 IU/dL or higher, which reduces spontaneous bleeds and joint damage.2,11,12 Prophylaxis requires life-long intravenous infusions two to three times per week due to the short half-lives of the clotting factors (endogenous/standard-acting FVIII and FIX half-lives are 8–12 and 18–24 h, respectively).2,5 Despite remarkably improved outcomes, prophylaxis fails to completely prevent bleeds and joint damage.13,14

Development of FVIII- or FIX-neutralizing alloinhibitory antibodies (inhibitors) is currently the most serious complication of treatment, as it makes replacement therapy ineffective and occurs in approximately 30% and 5% of patients with severe hemophilia A and B, respectively.15 Clinical management and burden of therapy are more challenging in inhibitor patients, especially in those with hemophilia B, up to 50% of whom develop severe allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, following administration of FIX.16,17 Patients with high-titer inhibitors (>5 Bethesda units [BU]/mL, where 1 BU/mL reduces clotting factor activity by 50%) require bypassing agents, such as recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) or activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC). These are less efficacious and require more frequent infusions than factor concentrates in non-inhibitor patients.2,18 Immune tolerance induction (ITI) therapy may be given to eradicate high-titer inhibitors, which entails many months or years of intensive, up to twice daily factor treatment and is only effective in approximately 70% and 30% of hemophilia A and B patients, respectively.19, 20, 21

Several extended half-life factor products (EHLs) have been launched in recent years, which permit maintaining higher trough levels or reducing the frequency of infusions.13 Modifications to increase factor half-life include its conjugation to polyethylene glycol (PEG),22 fusion to the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (IgG)23 or to albumin,24 and development of single-chain FVIII,25,26 which extend half-lives 1.2- to 2-fold for FVIII and 4- to 6-fold for FIX.22,23,27, 28, 29 Yet, in many settings treatment expenditures are significantly higher in patients who switch to EHLs, which often prohibits using them despite their ability to increase trough levels and thus optimize protection from bleeding.30, 31, 32

The limitations of standard therapies for patients with hemophilia, all of which are based on the same paradigm of replacing the missing protein, necessitate the search for better treatment options. This need is even more urgent in the case of patients with inhibitors, whose outcomes plummet upon development of alloinhibitory neutralizing antibodies. Many novel molecular therapies are currently being developed that promise to transform hemophilia care and patients’ quality of life. Gene therapy aims to provide sustained factor levels with a single treatment (Figure 1), while non-replacement therapies mimic procoagulant activity of the missing clotting factor or enhance coagulation by inhibiting physiological anticoagulants (Figure 2). Here, we summarize available data on these approaches, discuss their advantages and potential limitations, and forecast their impact on the management of hemophilia.

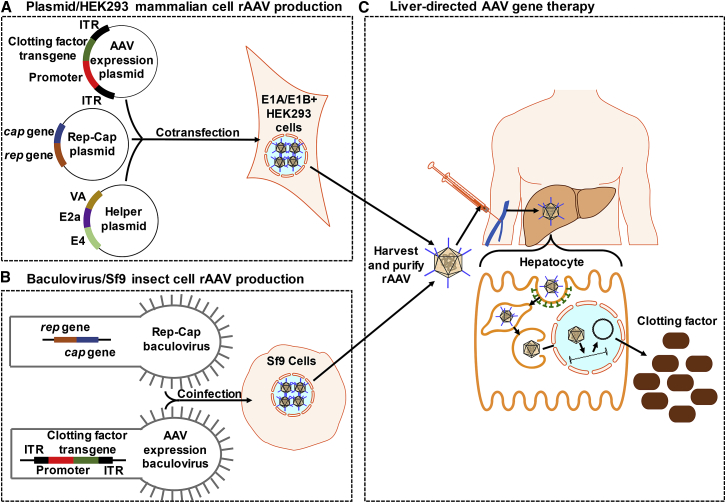

Figure 1.

AAV Gene Therapy

(A) Plasmid/HEK293 mammalian cell rAAV production: HEK293 cells are cotransfected with (1) AAV expression plasmid containing the clotting factor transgene and tissue-specific promoter, flanked by ITRs, (2) plasmid containing the rep and cap genes, and (3) helper plasmid containing adenovirus genes. (B) Baculovirus/Sf9 insect cell rAAV production: Sf9 cells are coinfected with (1) AAV expression baculovirus containing the clotting factor transgene and tissue-specific promoter, flanked by ITRs, and (2) baculovirus containing the rep and cap genes. (C) Liver-directed AAV gene therapy: rAAV is harvested by freeze-thawing transfected/infected cells, purified, and then injected intravenously. The transgene expression is targeted to hepatocytes using a liver-specific promoter and capsid with strong liver tropism. rAAV binds to a serotype-specific host cell receptor and is internalized by a clathrin-coated dynamin-dependent pathway into the endosomal compartment.33, 34, 35, 36 The rAAV is quickly transported using microtubules to the perinuclear region and undergoes conformational changes that expose regions of its capsid to allow for escape from the endosome and nuclear localization signals for trafficking into the nucleus.36, 37, 38 The clotting factor is expressed after AAV uncoats its capsid and converts to a circular double-stranded DNA episome by annealing of plus and minus strands delivered to the same cell or second-strand synthesis using host polymerase.39,40 rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus; ITR, inverted terminal repeat.

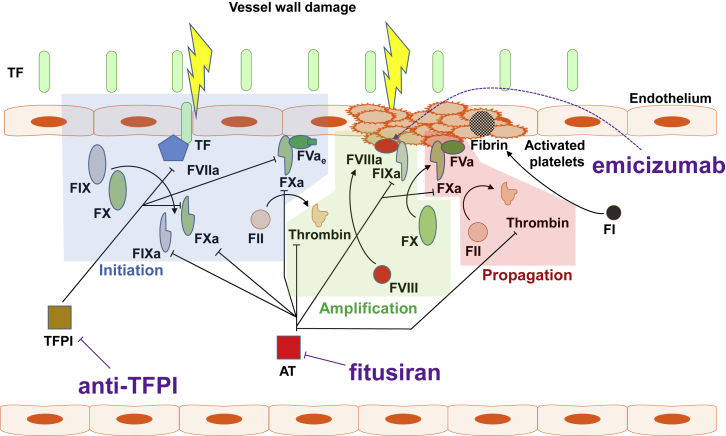

Figure 2.

Key Events and Physiologic Inhibitors of Secondary Hemostasis Targeted by Non-replacement Hemophilia Therapies

Upon vessel wall injury, normally subendothelial tissue factor (TF) is exposed to blood and binds to activated FVII (FVIIa), thus enhancing its catalytic activity. The TF-FVIIa complex generates small amounts of FIXa and FXa. FXa and early (partially activated) forms of FV (FVae) associate on negatively charged phospholipids (via calcium ions) exposed on damaged endothelial cells and activated platelets, where they form an early prothrombinase complex, which generates minute amounts of thrombin (initiation phase) by cleavage of FII (prothrombin). In the amplification phase, thrombin activates multiple coagulation factors, including cell surface-bound FVIII, FV, and FXI. FVIIIa enhances the catalytic activity of FIXa, which activates FX. FXa and thrombin-activated FV generated during the amplification phase now propel a thrombin burst on the surface of activated platelets (propagation phase), leading to cleavage of FI (fibrinogen) and formation of the fibrin clot.41,42, 43, 44

Emicizumab: FVIIIa in Disguise of an Antibody

Emicizumab is a subcutaneous humanized bispecific IgG4 monoclonal antibody that mimics a key function of activated FVIII (FVIIIa): bridging FIXa and the FX zymogen to accelerate activation of the latter. To that end, the antibody recognizes FIX/IXa with one Fab arm and FX/Xa with the other (Figure 3). Emicizumab is not recognized by FVIII-neutralizing alloinhibitory antibodies, so it remains effective in their presence and is now licensed for bleed prophylaxis in hemophilia A patients, both with and without FVIII inhibitors.45,46

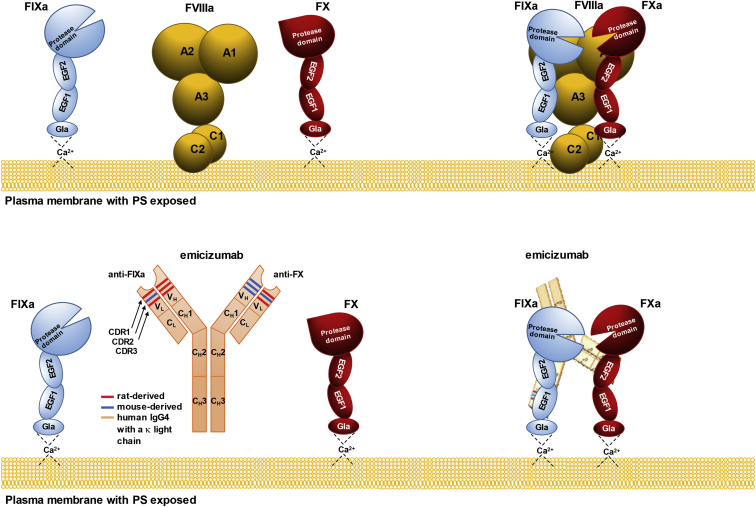

Figure 3.

Structure and Activity of FVIIIa and Emicizumab

FVIIIa forms a complex with activated FIX (FIXa, a serine protease) and FX (the zymogen), so that FIXa can activate the latter. In this reaction, FVIIIa functions as a molecular scaffold for FIXa, whose protease activity toward FX is otherwise 105- to 106-fold lower and insufficient to drive the thrombin burst and, ultimately, optimal blood coagulation. Emicizumab is an asymmetric humanized bispecific anti-FIXa/anti-FX antibody with mouse and rat complementarity determining regions (CDRs) grafted on a human immunoglobulin (IgG4) with a kappa light chain. While FVIIIa binds multiple sites on FIXa and FX, emicizumab recognizes single epitopes within epidermal growth factor-like domain 1 (EGF1) of FIXa and EGF2 of FX. Unlike FVIIIa, emicizumab does not bind negatively charged phospholipids (e.g., PS [phosphatidylserine]), but their presence is necessary for its procoagulant activity, which suggests that bridging FIXa and FX in proper orientation requires that they sit on the cell surface.47,48

Despite being able to mimic FVIIIa, emicizumab differs from it in several important ways that have implications for its efficacy, safety, and laboratory monitoring (Table 1). Unlike FVIII, which circulates inactive in the absence of bleeding, emicizumab does not require activation (it is always “on”).49 As a result, activated plasma thromboplastin time (aPTT, a clotting-based assay routinely used to monitor response to standard therapies) overestimates coagulation in patients on emicizumab, because its constant on state skips the time normally needed to generate FVIIIa.50 Other clotting-based assays also suffer from this problem, such as underestimation of FVIII inhibitor titers during Bethesda assays, which are further complicated by emicizumab retaining its activity despite the presence of FVIII inhibitors.51 Additionally, in contrast to FVIIIa, which loses activity upon spontaneous dissociation of non-covalently-bound A2 domain or cleavage by activated protein C, emicizumab is never inactivated.49 Emicizumab lacks phospholipid-binding sites, but its procoagulant activity still depends on negatively charged phospholipids. This probably limits its activity to the sites of blood vessel injury, where exposure of phosphatidylserine on the outer side of plasma membrane recruits coagulation factors with Gla domains (including FIX and FX).47,52 Emicizumab binds FIX/IXa and FX/Xa more weakly than FVIIIa binds FIXa and FX, which keeps emicizumab from sequestering FIX and FX zymogens and facilitates the release of FXa for its downstream reaction (thrombin generation).53 Despite emicizumab’s insusceptibility to activated protein C, inhibition of FVa therewith as well as inhibitory activities of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and antithrombin seem to regulate the procoagulant activity of emicizumab well enough.54,55

Table 1.

Differences between FVIII and Emicizumab

| Molecule Name | Structure | Sites of Interaction with Substrate (FIXa and FX) | Affinity | Binding Specificity | Role of Phospholipids | Activation and Inactivation | Route of Administration | Immunogenicity | Half-Life (days) | Relationship between Dose and Activity | Relative Procoagulant Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emicizumab | asymmetric bispecific humanized mAb; consists of a rat anti-FIX VH, a mouse anti-FX VH, and a common rat-mouse hybrid VL grafted on the human IgG4 framework with a κ light chain53,56 | binds single sites with each Fab arm within the EGF-like domain 1 of FIX/IXa and EGF-like domain 2 of FX/Xa48 | low (KD = 1.85 μM for FX and 1.52 μM for FIXa)48 | binds both zymogens (FIX and FX) and activated FIX and FX (FIXa and FXa)48 | does not bind phospholipids but its procoagulant activity still requires presence of phospholipids47 | activation not required (always “on”); not susceptible to inactivation by dissociation, cleavage, or by alloinhibitory FVIII-neutralizing antibodies47 | s.c. (86% bioavailability)53 | in clinical trials, 14/398 (3.5%) trial participants developed neutralizing anti-drug antibodies, 3 of whom showed decline in response to therapy and 1 of whom discontinued emicizumab and resumed pre-study treatment due to a loss of efficacy47 | 2147 | bell-shaped (peak at 265 μg/mL, >5-fold the plasma concentration on prophylaxis with emicizumab)47 |

50 μg/mL maintained in patients on prophylaxis is equivalent to ~15 IU/dL FVIII (1 IU FVIII activity per ~333 μg of emicizumab but the relationship is non-linear)47,48 |

| Factor VIII | heterodimeric glycoprotein consisting of metal ion-linked heavy (A1-A2-B domains) and light (A3-C1-C2 domains) chain49 | binds FIXa and FX at multiple sites across several domains | high (KD = 165 nM for FX and 7.3 nM for FIXa)57,58 | binds FIXa and FX (zymogen) only | binds negatively charged phospholipids via the light chain (C1 and C2 domain)49 | activated upon the onset of bleeding; inactivated by activated protein C, spontaneous dissociation of A2 domain, or by alloinhibitory FVIII-neutralizing antibodies | i.v. | 30% of patients with hemophilia A develop alloinhibitory FVIII-neutralizing antibodies (inhibitors) | 0.5 | linear | 1 IU of FVIII activity per ~0.2 μg of FVIII protein |

VH, heavy chain variable region; VL, light chain variable region; Ig, immunoglobulin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PK, pharmacokinetics; PD, pharmacodynamics; EGF, epidermal growth factor; s.c., subcutaneous(ly); i.v., intravenous(ly).

In clinical trials, emicizumab was administered prophylactically once a week, every other week, or every 4 weeks, and these three regimens have been used after licensure (G. Young et al., 2018, Am. Soc. Hematol., conference).45,46,59,60 In HAVEN 1 and 3 studies, the drug reduced bleeding rates in persons with hemophilia A with and without FVIII inhibitors by 79% and 68% compared to pre-emicizumab prophylaxis with standard bypassing agents (aPCC and rFVIIa) and FVIII, respectively.45,46 Management of breakthrough bleeds on emicizumab still requires standard therapies. While administration of FVIII concentrates in patients on emicizumab seems to be safe, several individuals with inhibitors developed thromboses or thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) after treatment with a higher dose of aPCC.45,46 FVIII probably outcompetes emicizumab for their common substrates (FIXa and FX) due to the lower affinity of the latter, thereby producing no synergistic effects. In contrast, aPCC contains several coagulation factors (FII, FVII, FIX, FX, and activated FVII), two of which are the substrates of emicizumab, and one of which (FIX) drives the synergistic effect of aPCC and emicizumab on thrombin generation.61 This is because in normal hemostasis the generation of FVIIIa is the limiting step in formation of the FVIIIa/FIXa/FX complex, while in FVIII-deficient plasma containing emicizumab, which is active en bloc and thereby available in excess immediately when bleeding occurs, the limiting step of the emicizumab/FIXa/FX complex formation is the generation of FIXa.47,51 The immunogenicity profile of emicizumab seems favorable and similar to other humanized therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (Table 1).62, 63, 64

The dosing regimens of emicizumab aim to maintain plasma concentration close to 50 μg/mL, which provide hemostatic activity equivalent to ∼15 IU/dL FVIII, estimated by comparing emicizumab with FVIII in thrombin generation assays. This is a major departure from 1 IU/dL FVIII trough levels (traditionally aimed for with standard FVIII concentrate prophylaxis), which likely translates into further reduced bleeding rates (G. Young et al., 2018, Am. Soc. Hematol., conference).47,65

Targeting Physiological Anticoagulants

Individuals with hemophilia who co-inherit prothrombotic mutations may show milder bleeding phenotypes. This observation prompted attempts to correct the bleeding phenotype in hemophilia by downregulating natural anticoagulants, thereby rebalancing hemostasis.66,67 Several approaches are currently under study in patients with hemophilia A and B, two of which are at the clinical stage: blocking TFPI using monoclonal antibodies, and knocking down antithrombin through RNA interference (RNAi). Potentially, anti-TFPI antibodies and fitusiran could be used to treat von Willebrand disease and some rare bleeding disorders (e.g., FVII deficiency), but available data are limited to in silico and in vitro studies.68, 69, 70

Anti-TFPI Antibodies

Several TFPI-targeting molecules have been investigated over the years, four of which (concizumab, BAY 1093884, marstacimab, and MG1113) are subcutaneous anti-TFPI antibodies that entered clinical trials including both hemophilia A and B patients with and without inhibitors. A phase 2 BAY 1093884 trial has now been terminated due to serious adverse events. TFPI brakes the initiation phase of coagulation by inactivating FXa (with its Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor domain 2, or K2) and the FVIIa-tissue factor (TF) complex (via the K1 domain). These two events proceed stepwise: the binding of FXa enables the inhibition of FVIIa-TF.41,71 Therefore, TFPI operates in a negative feedback loop that regulates the generation of FXa. Interestingly, partial TFPI deficiency is not a strong risk factor for thrombosis, but it may ameliorate the bleeding phenotype when co-inherited with hemophilia.66,67,72

The four antibodies that entered the clinic target K2 or both K1 and K2 domains of TFPI (Table 2). Since TFPI requires FXa to effectively modulate FVIIa, blocking the K2 domain unleashes both factors. This extends the initiation phase of coagulation, which thus generates more FXa (Figure 4). In hemophilic plasma, this may compensate for the insufficient FXa (and so thrombin) generation caused by deficiencies of FVIII or FIX. In the ongoing phase 2 trials, once daily prophylaxis with concizumab reduced annualized bleeding rates (ABRs) in patients with hemophilia A or B with inhibitors compared to on-demand treatment with rFVIIa.73

Table 2.

Anti-TFPI Antibodies that Entered Clinical Trials

| Anti-TFPI Antibody (Company) | Characteristics | Bioavailability (for s.c. Administration) | Ongoing Clinical Trials | Completed Clinical Trials | Frequency, Route, and Dose in Active Trials | Mean ABR | Immunogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concizumab, mAb 2021 (Novo Nordisk) | murine mAb, humanized (IgG4); epitope within the K2 domain of TFPI | 93%74,75 | phase 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03196297): efficacy and safety of once daily prophylaxis in patients with severe hemophilia A without inhibitors phase 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03196284):efficacy of once daily prophylaxis in hemophilia A and B patients with inhibitors |

phase 1 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02490787): multiple dose, safety, PK, and PD of concizumab in hemophilia A subjects | once daily s.c., loading dose 0.5 mg/kg followed by 0.15 mg/kg (with potential stepwise dose escalation to 0.25 mg/kg) | 7 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03196297, hemophilia A without inhibitors) 4.5 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03196284, hemophilia A and B with inhibitors) |

ADAs detected in 6/53 (3 NAbs) participants of ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03196297 and NCT03196284 studies, none of which caused a loss of efficacy73 |

| Marstacimab, PF-06741086 (Pfizer) | fully human (IgG1) mAb, selected from a phage display library of scFvs derived from non-immunized human donors and converted to IgG1; epitope within the K2 domain of TFPI | 100% (in cynomolgus)76 | phase 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03363321): safety, tolerability, and efficacy of long-term treatment in subjects with severe hemophilia A and B with or without inhibitors | phase 1 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02531815): safety, tolerability, PK, and PD of single ascending dose in healthy subjects only; phase 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02974855): safety, tolerability, PK, and PD multiple doses in subjects with severe hemophilia A and B, with or without inhibitors |

once weekly s.c., 3 doses tested: 150 mg (after the first loading dose of 300 mg), 300 mg (no loading dose), and 450 mg (no loading dose) | – | ADAs detected in 15/32 (3 NAbs) participants of ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02531815 study; all NAbs (3) detected 42 days after administration, when the drug effects had already dissipated, so impact on PK and PD unknown77 |

| BAY 1093884 (Bayer) | fully human (IgG2) mAb, selected from a phage display library of scFvs derived from non-immunized human donors and converted to IgG2; epitope encompasses K1 and K2 domains of TFPI78 | 52% or 61% depending on the assay (in cynomolgus)79 | none (phase 2 ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03597022 study has just been terminated due to serious adverse events) | phase 1 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02571569): safety, tolerability, and PK of increasing single doses and multiple doses in subjects with severe hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors phase 1 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03481946): PK and PD in patients with severe hemophilia A and B, with or without inhibitors |

– | – | no data |

| MG1113 (Green Cross) | murine mAb, humanized (IgG4)80 | no data | phase 1 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03855696): safety and tolerability of a single ascending dose in hemophilia A and B patients without inhibitors and healthy subjects | N/A | single dose s.c. and i.v., six doses: 0.5 mg/kg (s.c.), 1.7 mg/kg (s.c.), 3.3 mg/kg (s.c. and i.v.), 6.6 mg/kg (i.v.) in healthy subjects; 3.3 mg/kg (s.c.), 6.6 mg/kg, and 13.3 mg/kg (i.v.) in hemophilia subjects | – | N/A |

ABR, annualized bleeding rate; mAb, monoclonal antibody; s.c., subcutaneous(ly); Ig, immunoglobulin; scFv, single-chain variable fragment; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; PK, pharmacokinetics; PD, pharmacodynamics; NAb, neutralizing antibody, ADA, anti-drug antibody; N/A, not applicable.

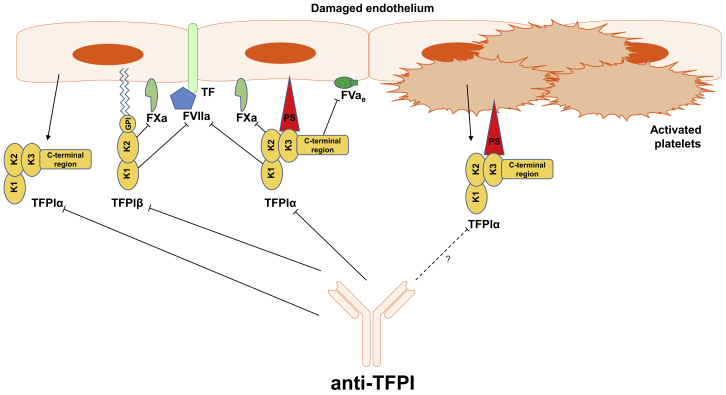

Figure 4.

Key Isoforms of Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor and Their Activities

Two predominant isoforms, tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI)α and TFPIβ, emerge through alternative splicing and so differ in structure and localization. TFPIα is the full-length isoform consisting of three Kunitz-type domains, one of which (K3) shows no inhibitory function, but it binds protein S (PS), which localizes the circulating TFPIα to cell membrane surfaces upon blood vessel injury. TFPIβ is a truncated form of TFPIα, missing part of the C terminus including the K3 domain, but instead it contains a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor, which moors it to the cell membrane. Both isoforms block FXa and the TF-FVIIa complex with K2 and K1 domains, respectively, but TFPIα displays one more mode of FXa inhibition, which is by blocking its association with early (partially activated) forms of FVa (FVae), and it operates in different mise-en-scènes. Endothelial cells and megakaryocytes are the main sites of TFPI expression. Megakaryocytes express TFPIα only, while endothelial cells produce both TFPIα and TFPIβ, so the GPI-anchored pool of TFPI resides on the endothelium. The plasma pool of TFPIα also comes from the endothelium, because the TFPIα synthesized by megakaryocytes is stored in platelets, which only release it upon activation. Although TFPIα is altogether the more abundant isoform, TFPIβ represents most of the TFPI that is readily available.41 Anti-TFPI antibodies currently evaluated in clinical trials block K2 or both K1 and K2 domains of TFPI.

Several issues common for all of these anti-TFPI antibodies transpire from the available data. They all exhibit target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD, whereby pharmacokinetics are affected by the drug’s high binding affinity).76,79,81,82 The key implication is the necessity for more frequent infusions than could be otherwise expected from an antibody, given their long half-lives. Consequently, the ongoing phase 2/3 trials administer anti-TFPI antibodies as often as once daily.74 Also, TMDD and compartmentalization of various TFPI isoforms complicate the search for a safe therapeutic window. For example, the highest dose (0.8 mg/kg) of concizumab used in a phase 1 multiple-dose trial, which normalized thrombin generation, also caused elevation of D-dimer and prothrombin F1+2 (prothrombotic markers) levels above the normal range, although the relevance of these markers in individuals with hemophilia is unknown and no evidence of thromboses was seen.74,75,83

Treatment of breakthrough bleeds will require standard therapies, because TFPI primarily acts on the initiation phase of coagulation, which is already shut down at the time of intervention in a typical acute bleeding scenario (Figure 1). Potential synergistic effects of anti-TFPI antibodies with standard therapies await elucidation. Recent in vitro and in vivo studies on interactions between concizumab and rFVIIa yielded conflicting results. While concizumab and rFVIIa showed synergistic effect on thrombin generation in vitro, no such effect emerged in hemophilic rabbits or cynomolguses.84 The authors propose that rFVIIa at pharmacological doses activates FX independent from TF on the surface of activated platelets in the propagation phase of coagulation, while TFPI only acts in the initiation phase.85 However, upon activation, platelets release their intracellular pool of TFPI, part of which remains on the platelet surface and may be blocked by anti-TFPI antibodies (Figure 4).86, 87, 88 Indeed, in hemophilic mice, platelet-derived TFPI seems to be a major regulator of bleeding.89 Alternatively, free rFVIIa may be less susceptible to inhibition by TFPI than in complex with TF.90

Fitusiran

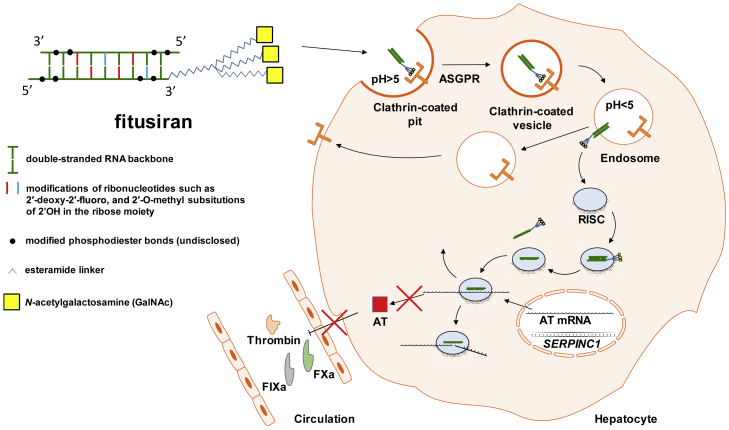

Fitusiran (ALN-AT3) is a subcutaneous double-stranded small interfering RNA (siRNA) that targets the transcript of the SERPINC1 gene, leading to its degradation by RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and thus preventing translation (Figure 5).91 SERPINC1 encodes antithrombin, a serine protease inhibitor (serpin) produced by hepatocytes, which irreversibly inactivates thrombin, FXa, and, to a lesser extent, FIXa, FXIa, FXIIa, kallikrein, and plasmin.92

Figure 5.

Antithrombin Knockdown by Fitusiran

Fitusiran is a double-stranded small interfering RNA (siRNA) with multiple chemical modifications, which protect it from degradation by nucleases and prevent innate immune sensing. The triantennary GalNAc moiety targets fitusiran to hepatocytes through asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR, also known as Ashwell-Morell receptor) and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Upon a drop in pH, the siRNA departs from ASGPR and exits the endosome. The cytosolic RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) captures the molecule and ejects one strand, leaving the antisense strand to bind to antithrombin (AT) mRNA and induce its sequence-specific cleavage and degradation. This thwarts translation of the AT transcript, leading to a drop in blood AT levels.93,94,95

Fitusiran targets a 23-nt region of the SERPINC1 mRNA (NM_000488.2 positions 815–837).96 The RNA backbone of fitusiran contains chemical modifications (including 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro and 2′-O-methyl substitutions in ribonucleotides and undisclosed replacements of phosphodiester linkages between them) that prevent its degradation by nucleases and recognition by Toll-like receptor (TLR)3 and TLR7, which are innate immune receptors sensing double-stranded RNAs.93,94,96,97 Also, the siRNA is conjugated to triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), which mediates its uptake by hepatocytes through asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), abundantly expressed in the liver.95,96 The antisense strands of siRNAs are stable within the RISC for weeks, so the same siRNA molecule may target multiple transcripts, which produces a durable knockdown, and so therapeutic effect (fitusiran is dosed once monthly in the ongoing trials). A few hundred siRNAs per cell are enough for efficient and sustained knockdown.95

Phase 3 trials of fitusiran are ongoing (Table 3). Data reported so far demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in thrombin generation, inversely correlating with reduction of antithrombin. A reduction in the antithrombin level of more than 75% from baseline elevated thrombin generation to non-hemophilic levels.98 In a phase 2 trial, which included patients with hemophilia A and B with and without inhibitors, such a drop in antithrombin levels reduced the overall median ABR to 1, with 48% of patients remaining bleed-free throughout the study. Breakthrough bleeds were treated with clotting factor concentrates or bypassing agents. The most serious adverse event was a fatal cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, which prompted suspension of all trials. The fatal case occurred after repeated infusions of high FVIII concentrate doses over more than 24 hours, which was contraindicated for trial participants. Importantly, the patient’s FVIII levels were never above the normal range during the intensive FVIII treatment. The trials resumed in December 2017.91 During the period of dosing suspension, AT levels recovered and rose to more than 60% of baseline after 5 months while thrombin generation decreased and ABR increased to 6.99

Table 3.

Fitusiran Trials

| Trial | Status | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Frequency, Route, and Dose | AT Reduction (%) | Mean (median) ABR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1, single-ascending and multiple-ascending dose, safety, tolerability, and PK in patients with moderate or severe hemophilia A and B | completed | NCT02035605 | once weekly 0.015–0.075 mg/kg s.c. or monthly 0.225–1.8 mg/kg s.c. | 70–89 | – |

| Phase 1/2, long-term safety and tolerability in patients with moderate or severe hemophilia A and B with or without inhibitors | ongoing | NCT02554773 | once monthly s.c., fixed dose 50 or 80 mg | 78–88 | 1.7 (1) |

| Phase 3 (ATLAS-INH): efficacy (ABR, HRQOL) of fitusiran relative to prior on-demand treatment with standard BPA in patients with hemophilia A and B with inhibitors | ongoing | NCT03417102 | once monthly s.c., fixed dose 80 mg | – | – |

| Phase 3 (ATLAS-A/B): efficacy (ABR, HRQOL) of fitusiran relative to prior on-demand treatment with CFC in patients with hemophilia A and B without inhibitors | ongoing | NCT03417245 | once monthly s.c., fixed dose 80 mg | – | – |

| Phase 3 (ATLAS-PPX): ABR and HRQOL relative to prior prophylaxis with CFC or standard BPA in patients with severe hemophilia A and B with or without inhibitors | ongoing | NCT03549871 | once monthly s.c., fixed dose 80 mg | – | – |

ABR, annualized bleeding rates; s.c., subcutaneous(ly); PK, pharmacokinetics; BPA, bypassing agent; ABR, annualized bleeding rate; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; CFC, clotting factor concentrate.

Gene Therapy

AAV Gene Therapy for Hemophilia B

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a non-pathogenic single-stranded DNA parvovirus that is naturally replication deficient in the absence of helper virus co-infection. Recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors lack sequences encoding Rep, Cap, and AAP (for replication, capsid structure, and promoting capsid assembly, respectively) and generally elicit only mild and transient innate immune responses compared to other viral vectors.100, 101, 102, 103, 104 Also, AAV integration into the host genome occurs inefficiently in the absence of the rep gene,105, 106, 107 reducing risks of genotoxicity. Efficient in vivo gene transfer, various viral capsids with strong tropism for the liver, and the ability to confer long-term gene expression in hepatocytes has made AAV the vector of choice for most hemophilia gene therapy clinical trials.108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114 Currently, AAV vectors are produced using two vastly different manufacturing platforms: HEK293 cells (Figure 1A) or Sf9 insect cell-based baculovirus expression vector system (Figure 1B). The vector in all current clinical trials is given intravenously, and the transgene is expressed from a liver-specific promoter (Figure 1C). This approach has resulted in therapeutic expression for more than a decade in large animal studies, and similarly in long-term expression of ∼5% of normal FIX levels in patients enrolled in early trials. Hurdles for the approach include pre-existing neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against some capsids that exclude some patients from receiving a specific vector product. Mild liver toxicity and CD8+ T cell responses to viral capsid during the first few months after vector administration have prompted the prophylactic or acute use of glucocorticoids upon a systemic rise in liver enzyme levels.

Results of early clinical trials prompted many refinements, such as codon-optimization for enhanced expression and elimination of potentially immune stimulatory CpG motifs from expression cassettes. Transgenes encoding wild-type FIX have been replaced by FIX variants with higher activity such as the Padua variant, which contains p.R338L single amino acid substitution and shows 8-fold higher activity.113, 114, 115, 116, 117 A 2015 phase 1/2 clinical trial (Spark/Pfizer; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02484092) infused 15 hemophilia B patients with low-dose AAV-Spark100 vector expressing FIX-Padua (SPK-9001, PF-06838435, fidanacogene elaparvovec) (Table 4).110,118 Patients typically reached levels of 30% of normal or greater at a reported dose of 5e11 vector genomes (vg)/kg and therefore no longer required factor infusions. Only two patients received glucocorticoids to stymie AAV capsid-specific cellular immune responses.110 A phase 3 study of SPK-9001 (Pfizer; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03861273) has begun and will test 55 additional patients. Similar levels of FIX activity have now been obtained using an AAV5 vector expressing FIX-Padua; although reported doses were substantially higher (2e13 vg/kg), no sustained AAV5 capsid-specific T cell response was detected (Uniqure; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03489291).109 This vector has now also entered phase 3 study (Uniqure; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03569891).

Table 4.

Current and Planned Gene Therapy Clinical Trials for Hemophilia B

| Sponsor | Treatment | Capsid Serotype | Promoter | Transgene Product | Dose (vg/kg) | Phase | Estimated Enrollment | Status | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freeline | FLT180a | synthetic | liver-specific | FIX-Padua | 6e11–2e12 | 1 | 18 | recruiting | NCT03369444 |

| LTFU | 2, 3 | 50 | recruiting | NCT03641703 | |||||

| Pfizer | fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001/PF-06838435) | Spark100 | ApoE/hAAT | FIX-Padua | 5e11 | 2 | 15 | active, not recruiting | NCT02484092 |

| n.d. | 3 | 55 | recruiting | NCT03861273 | |||||

| Sangamo | SB-FIX: integration of corrective FIX transgene into albumin locus by AAV6-delivered ZFN | AAV6 | – | – | n.d. | 1 | 12 | active, not recruiting | NCT02695160 |

| SGIMI | YUVA-GT-F901: autologous HSC/MSC, modified with lentivirus encoding FIX | – | – | – | – | 1 | 10 | not yet recruiting | NCT03961243 |

| Takeda | TAK-748 (SHP648/AskBio009/BAX 335) | scAAV8 | TTR | FIX-Padua | 2e11–3e12 | 1, 2 | 30 | active, not recruiting | NCT01687608 |

| SJCRH | scAAV2/8-LP1-FIX | scAAV2/8 | LP1 | FIX | 2e11–2e12 | 1 | 14 | active, not recruiting | NCT0979238 |

| UniQure | AMT-060 | AAV5 | liver-specific | FIX | 5e12–2e13 | 1, 2 | 10 | active, not recruiting | NCT02396342 |

| AMT-061 | liver-specific | FIX-Padua | 2e13 | 2 | 3 | recruiting | NCT03489291 | ||

| 3 | 56 | recruiting | NCT03569891 |

FIX, clotting factor IX; LTFU, long-term follow-up; n.d., not disclosed; AAV, adeno-associated virus; SGIMI, Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medial Institute; TTR, transthyretin; ApoE/hAAT, apolipoprotein E enhancer/human alpha 1-antitrypsin promoter; ZFN, zinc finger nuclease; SJCRH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

AAV Gene Therapy for Hemophilia A

AAV vectors with genomes exceeding the ∼5-kb capsid packaging limit are truncated and have substantially reduced efficiencies, which has made the ∼7-kb length of FVIII coding sequence a significant challenge in the pursuit of gene therapy for hemophilia A.119 A 2015 phase 1/2 trial (BioMarin; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02576795) tested first-in-human AAV-mediated FVIII gene transfer (BMN 270, valoctocogene roxaparvovec) in nine severe hemophilia A patients (Table 5).108 They used a B-domain deleted FVIII (BDD-FVIII) that leaves 14 codons in the B-domain for proteolytic cleavage/activation of FVIII (“FVIII-SQ”), retaining the potency of wild-type FVIII at only ∼4.4 kb.120, 121, 122 To further reduce size, a small hybrid liver-specific promoter (HLP) was constructed by combining the core enhancer from apolipoprotein E hepatic control region and three human alpha-1 antitrypsin promoter regulatory domains (ApoE/hAAT).123 AAV5 capsid was chosen in part because NAbs to AAV5 are less prevalent in humans than to AAV2 or AAV8.124,125 Vector doses of 6e13 vg/kg and 4e13 vg/kg normalized or nearly normalized FVIII levels at week 52 to a median of 88.6 and 31.7 IU/dL (measured by aPTT), respectively.108,126 For both cohorts, ABRs dropped and remained at a median of 0 bleeds/year (mean 0.7 bleeds/year) between year 2 and 3 after therapy, while FVIII usage decreased by >95%.108,126,127 Intriguingly, in both cohorts FVIII levels declined to a median of 45.7 IU/dL (6e13 vg/kg) and 23.5 IU/dL (4e13 vg/kg) during the second year of follow-up and continued to decline, albeit at the slower rates of 5.72 and 1.56 IU/dL per year, respectively, suggesting that durability of transgene expression may inversely correlate with vector dose. This is in contrast to the earliest successful hemophilia B trials, participants of which continue to show steady FIX levels 9 years after therapy. Also, hemophilia A dogs showed stable FVIII expression over a decade after gene therapy (P. Batty et al., 2019, Int. Soc. Thromb. Haemost., conference). These observations point to potential overarching principles underlying the FVIII decline in the BioMarin trials. FVIII is naturally synthesized in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), not in hepatocytes.128 Also, AAVs may transduce a smaller percentage of hepatocytes in humans compared to nearly complete transduction observed for vectors that are most optimal in murine and non-human primate (NHP) models.129 Perhaps uptake of the bulk of a large number of viral particles or ectopic overexpression of FVIII, which is known to have a potential for inducing ER stress responses, causes cellular stress due to unfolded protein response or other mechanisms. Alternative explanations would be a partial loss of vector genomes or transgene expression over time.130 Also, the latest trial updates drew more attention to discrepancies between FVIII activity assays, with aPTT (the most widely used assay in monitoring standard therapies) showing ∼1.6-fold higher FVIII activities in the trial participants than a chromogenic substrate assay (CSA).108,127 This aroused the expectation that all companies report CSA along with aPTT results. Animal studies suggest that CSAs are more reliable in measuring transgenic FVIII activity, but conclusive evidence has yet to be produced.131, 132, 133 This issue is germane to an ongoing debate over using factor level as the primary efficacy endpoint.134 BioMarin also initiated two studies in 2018, including a phase 3 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03392974) and a phase 1/2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03520712) evaluating patients with preexisting anti-AAV5 NAbs.

Table 5.

Current and Planned Gene Therapy Clinical Trials for Hemophilia A

| Sponsor | Treatment | Capsid Serotype | Promoter | Transgene Product | Dose (vg/kg) | Phase | Estimated Enrollment | Status | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayer | BAY2599023 (DTX201) | hu37 | liver-specific | BDD-FVIII | n.d. | 1, 2 | 30 | recruiting | NCT03588299 |

| BioMarin | valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN 270) | AAV5 | HLP | BDD-FVIII | 6e12–6e13 | 1, 2 | 15 | active, not recruiting | NCT02576795 |

| 6e13 | 3 | 130 | recruiting | NCT03370913 | |||||

| 4e13 | 3 | 40 | recruiting | NCT03392974 | |||||

| valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN 270) in patients with AAV5 antibodies | 6e13 | 1, 2 | 10 | enrolling by invitation | NCT03520712 | ||||

| MCW | autologous CD34 + PBSC, modified with lentivirus encoding BDD-FVIII | – | – | – | – | 1 | 5 | not yet recruiting | NCT03818763 |

| Sangamo | SB-525 | AAV2/6 | liver-specific | BDD-FVIII | 9e11–3e13 | 1, 2 | 20 | recruiting | NCT03061201 |

| SGIMI | YUVA-GT-F801: autologous HSC/MSC modified with lentivirus encoding FVIII | – | – | – | – | 1 | 10 | not yet recruiting | NCT03217032 |

| Takeda | TAK-755 (formerly BAX 888/SHP654) | AAV8 | TTR | BDD-FVIII | n.d. | 1, 2 | 10 | recruiting | NCT03370172 |

| Spark | SPK-8011 | Spark200 | liver-specific | BDD-FVIII | 5e11–2e12 | 1, 2 | 30 | recruiting | NCT03003533 |

| SPK-8016 in patients with FVIII inhibitors | n.d. | BDD-FVIII | dose-finding | 1, 2 | 30 | recruiting | NCT03734588 | ||

| UCL/St. Jude | AAV2/8-HLP-FVIII-V3 | AAV2/8 | HLP | FVIII-V3 | 6e11–6e12 | 1 | 18 | recruiting | NCT03001830 |

BDD-FVIII, B-domain deleted clotting factor VIII; n.d., not disclosed; AAV, adeno-associated virus; HLP, hybrid liver-specific promoter; MCW, Medical College of Wisconsin; SGIMI, Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medial Institute; TTR, transthyretin; UCL, University College London; FIX, clotting factor IX; ApoE/hAAT, apolipoprotein E enhancer/human alpha 1-antitrypsin promoter; ZFN, zinc finger nuclease.

Several additional hemophilia A trials have been initiated by other entities (Table 5). A 2016 trial (Spark; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03003533) administered a bioengineered AAV8-expressing BDD-FVIII to 12 patients with hemophilia A at 5e11–2e12 vg/kg. Low and middle doses of vector resulted in mean FVIII levels of 13 IU/dL at 66 weeks and 15 IU/dL at 46 weeks, respectively, and >97% reduction in ABRs and FVIII usage.135 A 2017 phase 1/2 trial (University College London and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03001830) administered two doses of AAV2/8 expressing a codon-optimized FVIII transgene under an HLP promoter, into three severe hemophilia A patients.123,136 Their unique BDD-FVIII transgene contains a 17-aa peptide with six N-glycosylation sites (FVIII-V3), which improved FVIII expression 3-fold in mice compared to the FVIII-SQ.136 In 2017, Sangamo began a phase 1/2 study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03061201) infusing SB-525, an AAV2/6-expressing BDD-FVIII under a liver-specific promoter, into patients with severe hemophilia A. The two higher doses (1e13 and 3e13 vg/kg) increased FVIII levels to mild hemophilia and normal levels (when measured by aPTT), respectively, and found the same discrepancies between aPTT and CSA as in the BioMarin studies.137,138

In preclinical studies, uniQure is developing an AAV5-mediated gene therapy using a FIX variant with three amino acid substitutions (p.V181I, p.K265A, p.I383V), which corrects the hemophilia A phenotype by allowing FIX to function independently of FVIII (FIX-FIAV), and potentially could be used in patients with FVIII inhibitors.139 FIX-FIAV has ∼30% activity of FVIII and is well tolerated in NHPs, with sustained expression beyond 14 weeks. In hemophilia A mice, clotting activity was ∼5% normal by the fifth week after vector administration.

In Vivo Gene Editing Therapies for Hemophilia

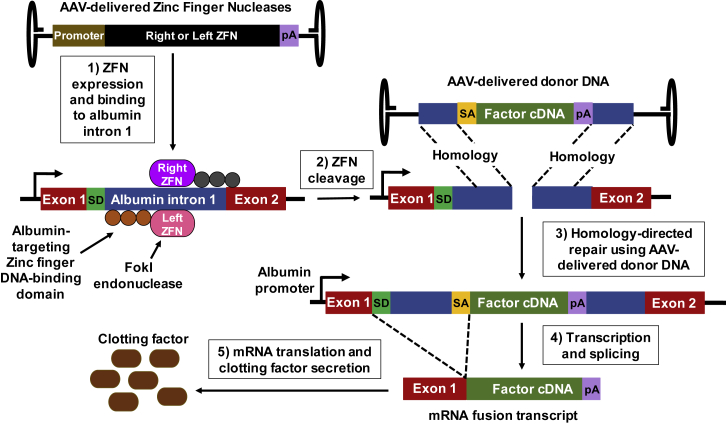

A 2018 phase 1 trial (Sangamo; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02695160) infused SB-FIX, a hemophilia B gene therapy consisting of three liver-tropic AAV2/6 vectors, each delivering one of the three components: a right or left zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) or normal F9 transgene. The ZFNs are designed to place the normal copy of the clotting factor gene within the albumin intron 1, under control of the endogenous albumin locus promoter (Figure 6). Preclinical studies showed that co-delivering AAV8 containing a ZFN pair targeting murine albumin (intron 1) with AAV8 containing a splice acceptor signal, promoterless F9 transgene (exons 2–8), and poly(A) sequence flanked by arms homologous to intron 1 can increase FIX levels proportionally to vector dose.140, 141, 142 Even when only 0.5% of the murine transcripts were mutated, high levels of FIX were sustained for more than a year, with no change in plasma albumin.

Figure 6.

Gene Editing by AAV-Delivered ZFN and Donor DNA Template

The zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) are designed to place the normal copy of the clotting factor gene within the albumin intron 1, under control of the endogenous albumin locus promoter. Three adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors are delivered, each providing one of the three components: a right or left ZFN or clotting factor cDNA donor template.140,141,143 (1) The AAV-expressed ZFN fuses a DNA-cleavage domain (FokI endonuclease) to a zinc finger DNA-binding domain. (2) The ZFN binding domain targets a specific sequence and then the cleavage domain induces a double-strand break. (3) The double-strand break can be repaired by homologous recombination if a DNA donor template is present with flanking arms homologous to the DNA at the ZFN cleavage site. (4) Flanking the clotting factor cDNA is a poly(A) sequence (pA) and a splice acceptor signal (SA), which splices the transcribed clotting factor RNA to the splice donor (SD) of albumin exon 1 RNA to produce an mRNA fusion transcript. (5) The mRNA fusion transcript is translated into secreted clotting factor protein.

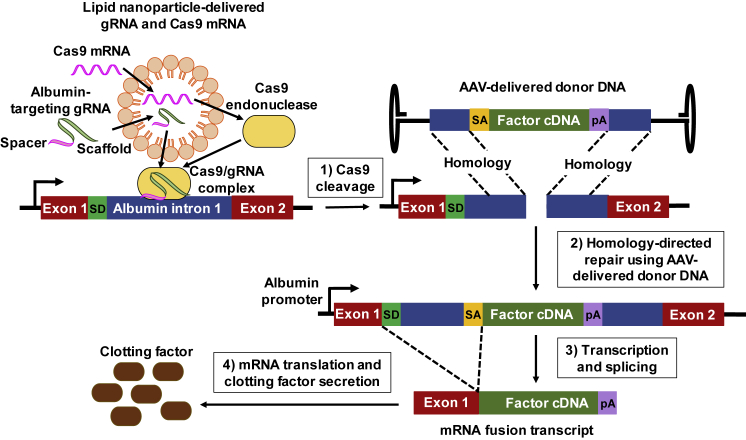

While ZFNs are the only in vivo gene editing system in hemophilia clinical trials currently, others such as CRISPR/Cas9 are being investigated in preclinical studies. The CRISPR/Cas9 system consists of a guide RNA (gRNA), which is a combination of two single-stranded RNAs, CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and transactivating crRNA (tracrRNA), and a nuclease (Cas9) that form the Cas9-gRNA complex.144 The gRNA scans the genome to look for a complementary sequence known as the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) and then Cas9 cleaves if the adjacent DNA sequence also matches the remaining gRNA. The double-strand break can be repaired by homologous recombination if a DNA donor template is present that has flanking arms homologous to the DNA at the Cas9 cleavage site (Figure 7). A dual AAV approach codelivering the Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 and FIX-encoding transgenes has been used to correct hemophilia B in mice.145 In this approach, the F9 transgene was targeted to exon 2 of the endogenous F9 locus. Intellia Therapeutics is testing codelivery of lipid-nanoparticle-encapsulated CRISPR/Cas9 components and an AAV containing a F9 transgene cDNA donor template in NHPs.146 They have achieved therapeutic levels of FIX after targeting the DNA into intron 1 of the albumin locus. Applied StemCell is also using the same strategy to correct hemophilia A in NHP and humanized-liver mouse models (H. Chen et al., 2019, Am. Soc. Gene Cell Ther., conference).147

Figure 7.

Gene Editing by Lipid Nanoparticle-Delivered CRISPR/Cas9 and AAV-Delivered Donor DNA

The CRISPR/Cas9 system consists of guide RNA (gRNA), which is a combination of two single-stranded RNAs, CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and transactivating crRNA (tracrRNA), and a nuclease (Cas9) that form the Cas9-gRNA complex.144 The CRISPR/Cas9 components can be delivered by lipid nanoparticle in RNA form.146 (1) The gRNA scans the genome for a complementary sequence known as the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site, and cleavage by Cas9 occurs if the adjacent DNA sequence also matches the remaining gRNA.144 (2) The double-strand break can be repaired by homologous recombination if a DNA donor template, delivered by adeno-associated virus (AAV), is present with flanking arms homologous to the DNA at the Cas9 cleavage site. (3) Flanking the clotting factor cDNA is a poly(A) sequence (pA) and a splice acceptor signal (SA), which splices the transcribed clotting factor RNA to the splice donor (SD) of albumin exon 1 RNA to produce an mRNA fusion transcript. (4) The mRNA fusion transcript is translated into secreted clotting factor protein.

Both Cas9- and ZFN-based gene-editing systems prompt additional safety considerations related to at least transient and potentially constitutive expression of prokaryotic nucleases along with the therapeutic transgene. Also, both systems pose an unclear risk of off-target DNA mutagenesis.148,149

Immune Tolerance Induction by Liver Gene Transfer

Studies in both canine and murine models of hemophilia show that liver-directed gene therapy can induce tolerance against FVIII or FIX, through regulatory T cell induction.150, 151, 152, 153 Hepatic gene transfer with AAV2/8-expressing FIX was shown to reverse preexisting anti-FIX NAbs and desensitize anaphylaxis-prone hemophilia B mice.154 These findings are further supported by the lack of reported inhibitors in any of the liver-directed AAV clinical trials in hemophilia patients.108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114

Ex Vivo Gene Therapies for Hemophilia

Many gene therapy studies employ lentiviral vectors, which integrate into host genomes. These have several advantages over AAV, including avoidance of gene dilution as the transgene is replicated with the host genome, lower prevalence of preexisting anti-vector NAbs, and increased packaging limits (∼8–10 kb).119,155 However, integration is a concern if it occurs near a transcription start site and transactivates a proto-oncogene.156, 157, 158 However, lentiviruses preferentially integrate within transcription units and thus are less likely to be genotoxic,159 and multiple clinical trials involving lentiviral-mediated gene therapy for other diseases have not observed insertional mutagenesis.160, 161, 162

While in animal models lentiviruses can generate stable FIX expression when targeted to hepatocytes,163 lentiviral clinical trials have focused on ex vivo transduction.160,161,164,165 A phase 1 trial in 2019 (Medical College of Wisconsin; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03818763) plans to use a lentiviral vector to deliver the FVIII gene, under a platelet-specific promoter, into autologous hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) ex vivo, and then infuse these cells into hemophilia A patients.166, 167, 168 Platelets are a site for synthesis/storage of von Willebrand factor (VWF), which forms a complex with FVIII and might help retain FVIII intracellularly until it is needed.168 In mice, this strategy was shown to protect FVIII from inactivation by inhibitors.169

Future Directions in Hemophilia Treatment

After decades of stagnation, hemophilia care has become an extremely fertile environment spurring a myriad of new technologies, many of which have reached the clinic. Emicizumab, now licensed for bleed prophylaxis in hemophilia A with and without inhibitors, was the first to break the paradigm of frequent intravenous infusions and seesaw PK. This creates unique opportunities to improve outcomes, including in very young children, which has been unfeasible with standard therapies.170,171 Inhibitors of natural anticoagulants, including fitusiran and anti-TFPI antibodies, are far along in clinical trials, and, if licensed, will greatly facilitate prophylaxis in hemophilia A and B in general, and patients with inhibitors in particular.172 Hemophilia B patients with inhibitors, who have been clinically the most underserved subpopulation, may benefit the most.

Historically, gene therapy has been the holy grail of hemophilia care, and its curative potential became tangible with several approaches producing normal levels of FVIII or FIX in hemophilia patients. The field has made great strides since its underwhelming beginnings and continues to evolve with still much room for improvement. AAV vectors have become the workhorse for both gene addition and correction, and future research will focus on perfecting capsid, transgene, and promoter designs in pursuit of better transduction efficiencies, immunological inertness, and predictability of therapeutic effect. Compared to almost 100% transduction efficiencies in animal models, the estimated few percent of hepatocytes transduced in humans leaves a lot to be desired in terms of achieving high protein expression without risking protein overload cellular stress.129 Also, while all of the ongoing clinical trials for hemophilia A and B target hepatocytes, FVIII is naturally expressed in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells,173,174 which will drive attempts to retarget AAVs for hemophilia A to the liver endothelium. Cancer gene therapy has made remarkable progress in vector engineering to target otherwise non-permissive cells, which may inform such efforts in hemophilia.175

Future treatment options may include prophylactic immune tolerance induction to prevent development of FVIII and FIX inhibitors. Oral tolerance induction using transplastomic lettuce expressing FVIII or FIX fused to a transmucosal carrier is at the forefront of research in this area.176 Such bioencapsulated factors can be ingested, cross the intestinal epithelium, and induce regulatory T cells within the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT).177,178 Murine and canine studies show that this strategy can reduce or prevent inhibitor formation, making it a likely candidate for clinical trials.

With this expanding tool chest, clinicians and patients are looking at a promising future but also entering an uncharted territory. Safety will need to remain a top priority with the legacy of medical disasters that plagued the hemophilia community in the past.179 Nevertheless, a new revolution in hemophilia treatment is now in full gear.

Author Contributions

J.S.S.B., K.M.H., R.W.H., and R.K. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

R.W.H. serves on the scientific advisory boards of Applied Genetic Technologies Corporation (AGTC) and Ally Therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R01 AI51390 (to R.W.H.), NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL131093, R01 HL133191, R01 HL097088, and U54 HL142012 (to R.W.H.), and a Bayer Hemophilia Award to R.K.

Contributor Information

Roland W. Herzog, Email: rwherzog@iu.edu.

Radoslaw Kaczmarek, Email: rkaczmar@iu.edu.

References

- 1.World Federation of Hemophilia . World Federation of Hemophilia; 2017. Report of the Annual Global Survey 2016.http://www1.wfh.org/publications/files/pdf-1690.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava A., Brewer A.K., Mauser-Bunschoten E.P., Key N.S., Kitchen S., Llinas A., Ludlam C.A., Mahlangu J.N., Mulder K., Poon M.C., Street A., Treatment Guidelines Working Group on Behalf of the World Federation of Hemophilia Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19:e1–e47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannucci P.M., Tuddenham E.G.D. The hemophilias—from royal genes to gene therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1773–1779. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stonebraker J.S., Bolton-Maggs P.H.B., Soucie J.M., Walker I., Brooker M. A study of variations in the reported haemophilia A prevalence around the world. Haemophilia. 2010;16:20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrijvers L.H., Schuurmans M.J., Fischer K. Promoting self-management and adherence during prophylaxis: evidence-based recommendations for haemophilia professionals. Haemophilia. 2016;22:499–506. doi: 10.1111/hae.12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyvandi F., Asselta R., Mannucci P.M. Autosomal recessive deficiencies of coagulation factors. Rev. Clin. Exp. Hematol. 2001;5:369–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-0734.2001.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roosendaal G., Lafeber F.P. Pathogenesis of haemophilic arthropathy. Haemophilia. 2006;12(Suppl 3):117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melchiorre D., Manetti M., Matucci-Cerinic M. Pathophysiology of hemophilic arthropathy. J. Clin. Med. 2017;6:E63. doi: 10.3390/jcm6070063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris C.J., Blake D.R., Wainwright A.C., Steven M.M. Relationship between iron deposits and tissue damage in the synovium: an ultrastructural study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1986;45:21–26. doi: 10.1136/ard.45.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouw S.C., van den Berg H.M., Oldenburg J., Astermark J., de Groot P.G., Margaglione M., Thompson A.R., van Heerde W., Boekhorst J., Miller C.H. F8 gene mutation type and inhibitor development in patients with severe hemophilia A: systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2012;119:2922–2934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aledort L.M., Haschmeyer R.H., Pettersson H., The Orthopaedic Outcome Study Group A longitudinal study of orthopaedic outcomes for severe factor-VIII-deficient haemophiliacs. J. Intern. Med. 1994;236:391–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astermark J., Petrini P., Tengborn L., Schulman S., Ljung R., Berntorp E. Primary prophylaxis in severe haemophilia should be started at an early age but can be individualized. Br. J. Haematol. 1999;105:1109–1113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Mackensen S., Kalnins W., Krucker J., Weiss J., Miesbach W., Albisetti M., Pabinger I., Oldenburg J. Haemophilia patients’ unmet needs and their expectations of the new extended half-life factor concentrates. Haemophilia. 2017;23:566–574. doi: 10.1111/hae.13221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miesbach W., O’Mahony B., Key N.S., Makris M. How to discuss gene therapy for haemophilia? A patient and physician perspective. Haemophilia. 2019;25:545–557. doi: 10.1111/hae.13769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Key N.S. Inhibitors in congenital coagulation disorders. Br. J. Haematol. 2004;127:379–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bon A., Morfini M., Dini A., Mori F., Barni S., Gianluca S., de Martino M., Novembre E. Desensitization and immune tolerance induction in children with severe factor IX deficiency; inhibitors and adverse reactions to replacement therapy: a case-report and literature review. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2015;41:12. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibata M., Shima M., Misu H., Okimoto Y., Giddings J.C., Yoshioka A. Management of haemophilia B inhibitor patients with anaphylactic reactions to FIX concentrates. Haemophilia. 2003;9:269–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witmer C., Young G. Factor VIII inhibitors in hemophilia A: rationale and latest evidence. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2013;4:59–72. doi: 10.1177/2040620712464509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruse-Jarres R. Current controversies in the formation and treatment of alloantibodies to factor VIII in congenital hemophilia A. Hematology (Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program) 2011;2011:407–412. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wight J., Paisley S., Knight C. Immune tolerance induction in patients with haemophilia A with inhibitors: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2003;9:436–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kempton C.L., Meeks S.L. Toward optimal therapy for inhibitors in hemophilia. Blood. 2014;124:3365–3372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konkle B.A., Stasyshyn O., Chowdary P., Bevan D.H., Mant T., Shima M., Engl W., Dyck-Jones J., Fuerlinger M., Patrone L. Pegylated, full-length, recombinant factor VIII for prophylactic and on-demand treatment of severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2015;126:1078–1085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-630897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahlangu J., Powell J.S., Ragni M.V., Chowdary P., Josephson N.C., Pabinger I., Hanabusa H., Gupta N., Kulkarni R., Fogarty P., A-LONG Investigators Phase 3 study of recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein in severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2014;123:317–325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-529974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santagostino E., Martinowitz U., Lissitchkov T., Pan-Petesch B., Hanabusa H., Oldenburg J., Boggio L., Negrier C., Pabinger I., von Depka Prondzinski M., PROLONG-9FP Investigators Study Group Long-acting recombinant coagulation factor IX albumin fusion protein (rIX-FP) in hemophilia B: results of a phase 3 trial. Blood. 2016;127:1761–1769. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-669234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zollner S.B., Raquet E., Müller-Cohrs J., Metzner H.J., Weimer T., Pragst I., Dickneite G., Schulte S. Preclinical efficacy and safety of rVIII-SingleChain (CSL627), a novel recombinant single-chain factor VIII. Thromb. Res. 2013;132:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahlangu J., Kuliczkowski K., Karim F.A., Stasyshyn O., Kosinova M.V., Lepatan L.M., Skotnicki A., Boggio L.N., Klamroth R., Oldenburg J., AFFINITY Investigators Efficacy and safety of rVIII-SingleChain: results of a phase 1/3 multicenter clinical trial in severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2016;128:630–637. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-687434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell J.S., Pasi K.J., Ragni M.V., Ozelo M.C., Valentino L.A., Mahlangu J.N., Josephson N.C., Perry D., Manco-Johnson M.J., Apte S., B-LONG Investigators Phase 3 study of recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein in hemophilia B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2313–2323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graf L. Extended half-life factor VIII and factor IX preparations. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2018;45:86–91. doi: 10.1159/000488060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klamroth R., Simpson M., von Depka-Prondzinski M., Gill J.C., Morfini M., Powell J.S., Santagostino E., Davis J., Huth-Kühne A., Leissinger C. Comparative pharmacokinetics of rVIII-SingleChain and octocog alfa (Advate®) in patients with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2016;22:730–738. doi: 10.1111/hae.12985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Z.-Y., Koerper M.A., Johnson K.A., Riske B., Baker J.R., Ullman M., Curtis R.G., Poon J.-L., Lou M., Nichol M.B. Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 2015;18:457–465. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2015.1016228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson K.A., Zhou Z.-Y. Costs of care in hemophilia and possible implications of health care reform. Hematology (Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program) 2011;2011:413–418. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tortella B.J., Alvir J., McDonald M., Spurden D., Fogarty P.F., Chhabra A., Pleil A.M. Real-world analysis of dispensed IUs of coagulation factor IX and resultant expenditures in hemophilia B patients receiving standard half-life versus extended half-life products and those switching from standard half-life to extended half-life products. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2018;24:643–653. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.17212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akache B., Grimm D., Pandey K., Yant S.R., Xu H., Kay M.A. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J. Virol. 2006;80:9831–9836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartlett J.S., Wilcher R., Samulski R.J. Infectious entry pathway of adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 2000;74:2777–2785. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2777-2785.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan D., Li Q., Kao A.W., Yue Y., Pessin J.E., Engelhardt J.F. Dynamin is required for recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J. Virol. 1999;73:10371–10376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10371-10376.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao P.-J., Samulski R.J. Cytoplasmic trafficking, endosomal escape, and perinuclear accumulation of adeno-associated virus type 2 particles are facilitated by microtubule network. J. Virol. 2012;86:10462–10473. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00935-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y., Joo K.I., Wang P. Endocytic processing of adeno-associated virus type 8 vectors for transduction of target cells. Gene Ther. 2013;20:308–317. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonntag F., Bleker S., Leuchs B., Fischer R., Kleinschmidt J.A. Adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids with externalized VP1/VP2 trafficking domains are generated prior to passage through the cytoplasm and are maintained until uncoating occurs in the nucleus. J. Virol. 2006;80:11040–11054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01056-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nonnenmacher M., Weber T. Intracellular transport of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Gene Ther. 2012;19:649–658. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou X., Zeng X., Fan Z., Li C., McCown T., Samulski R.J., Xiao X. Adeno-associated virus of a single-polarity DNA genome is capable of transduction in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:494–499. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood J.P., Ellery P.E.R., Maroney S.A., Mast A.E. Biology of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Blood. 2014;123:2934–2943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-512764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mackman N., Tilley R.E., Key N.S. Role of the extrinsic pathway of blood coagulation in hemostasis and thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:1687–1693. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolberg A.S., Campbell R.A. Thrombin generation, fibrin clot formation and hemostasis. Transfus. Apheresis Sci. 2008;38:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orfeo T., Brummel-Ziedins K.E., Gissel M., Butenas S., Mann K.G. The nature of the stable blood clot procoagulant activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9776–9786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707435200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahlangu J., Oldenburg J., Paz-Priel I., Negrier C., Niggli M., Mancuso M.E., Schmitt C., Jiménez-Yuste V., Kempton C., Dhalluin C. Emicizumab prophylaxis in patients who have hemophilia A without inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:811–822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oldenburg J., Mahlangu J.N., Kim B., Schmitt C., Callaghan M.U., Young G., Santagostino E., Kruse-Jarres R., Negrier C., Kessler C. Emicizumab prophylaxis in hemophilia A with inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:809–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kitazawa T., Shima M. Emicizumab, a humanized bispecific antibody to coagulation factors IXa and X with a factor VIIIa-cofactor activity. Int. J. Hematol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12185-018-2545-9. Published online October 22, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitazawa T., Esaki K., Tachibana T., Ishii S., Soeda T., Muto A., Kawabe Y., Igawa T., Tsunoda H., Nogami K. Factor VIIIa-mimetic cofactor activity of a bispecific antibody to factors IX/IXa and X/Xa, emicizumab, depends on its ability to bridge the antigens. Thromb. Haemost. 2017;117:1348–1357. doi: 10.1160/TH17-01-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lenting P.J., Denis C.V., Christophe O.D. Emicizumab, a bispecific antibody recognizing coagulation factors IX and X: how does it actually compare to factor VIII? Blood. 2017;130:2463–2468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-801662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nogami K., Soeda T., Matsumoto T., Kawabe Y., Kitazawa T., Shima M. Routine measurements of factor VIII activity and inhibitor titer in the presence of emicizumab utilizing anti-idiotype monoclonal antibodies. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018;16:1383–1390. doi: 10.1111/jth.14135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knight T., Callaghan M.U. The role of emicizumab, a bispecific factor IXa- and factor X-directed antibody, for the prevention of bleeding episodes in patients with hemophilia A. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2018;9:319–334. doi: 10.1177/2040620718799997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tavoosi N., Davis-Harrison R.L., Pogorelov T.V., Ohkubo Y.Z., Arcario M.J., Clay M.C., Rienstra C.M., Tajkhorshid E., Morrissey J.H. Molecular determinants of phospholipid synergy in blood clotting. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23247–23253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sampei Z., Igawa T., Soeda T., Okuyama-Nishida Y., Moriyama C., Wakabayashi T., Tanaka E., Muto A., Kojima T., Kitazawa T. Identification and multidimensional optimization of an asymmetric bispecific IgG antibody mimicking the function of factor VIII cofactor activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noguchi-Sasaki M., Soeda T., Ueyama A., Muto A., Hirata M., Kitamura H., Fujimoto-Ouchi K., Kawabe Y., Nogami K., Shima M., Kitazawa T. Emicizumab, a bispecific antibody to factors IX/IXa and X/Xa, does not interfere with antithrombin or TFPI activity in vitro. TH Open. 2018;2:e96–e103. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1636538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yada K., Nogami K., Shinozawa K., Kitazawa T., Hattori K., Amano K., Fukutake K., Shima M. Emicizumab-mediated haemostatic function in patients with haemophilia A is down-regulated by activated protein C through inactivation of activated factor V. Br. J. Haematol. 2018;183:257–266. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitazawa T., Igawa T., Sampei Z., Muto A., Kojima T., Soeda T., Yoshihashi K., Okuyama-Nishida Y., Saito H., Tsunoda H. A bispecific antibody to factors IXa and X restores factor VIII hemostatic activity in a hemophilia A model. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1570–1574. doi: 10.1038/nm.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeyama M., Wakabayashi H., Fay P.J. Factor VIII light chain contains a binding site for factor X that contributes to the catalytic efficiency of factor Xase. Biochemistry. 2012;51:820–828. doi: 10.1021/bi201731p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffiths A.E., Rydkin I., Fay P.J. Factor VIIIa A2 subunit shows a high affinity interaction with factor IXa: contribution of A2 subunit residues 707-714 to the interaction with factor IXa. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:15057–15064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.456467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jimenez-Yuste V., Shima M., Fukutake K., Lehle M., Chebon S., Retout S., Portron A., Levy G.G. Emicizumab subcutaneous dosing every 4 weeks for the management of hemophilia A: preliminary data from the pharmacokinetic run-in cohort of a multicenter, open-label, phase 3 study (HAVEN 4) Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):86. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pipe S., Jiménez‐Yuste V., Shapiro A., Key N., Podolak‐Dawidziak M., Hermans C., Peerlinck K., Lehle M., Chebon S., Portron A. Emicizumab subcutaneous dosing every 4 weeks is safe and efficacious in the control of bleeding in persons with hemophilia A (PwHA) with and without inhibitors: results from phase 3 HAVEN 4 study. Haemophilia. 2008;24(Suppl 5):212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hartmann R., Feenstra T., Valentino L., Dockal M., Scheiflinger F. In vitro studies show synergistic effects of a procoagulant bispecific antibody and bypassing agents. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018;16:1580–1591. doi: 10.1111/jth.14203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baker M.P., Reynolds H.M., Lumicisi B., Bryson C.J. Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics: the key causes, consequences and challenges. Self Nonself. 2010;1:314–322. doi: 10.4161/self.1.4.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bloem K., Hernández-Breijo B., Martínez-Feito A., Rispens T. Immunogenicity of therapeutic antibodies: monitoring antidrug antibodies in a clinical context. Ther. Drug Monit. 2017;39:327–332. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paz-Priel I., Chang T., Asikanius E., Chebon S., Emrich T., Fernandez E., Kuebler P., Schmitt C. Immunogenicity of Emicizumab in people with hemophilia A (PwHA): results from the HAVEN 1–4 studies. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):633. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoneyama K., Schmitt C., Kotani N., Levy G.G., Kasai R., Iida S., Shima M., Kawanishi T. A pharmacometric approach to substitute for a conventional dose-finding study in rare diseases: example of phase III dose selection for emicizumab in hemophilia A. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018;57:1123–1134. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0616-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franchini M., Montagnana M., Targher G., Veneri D., Zaffanello M., Salvagno G.L., Manzato F., Lippi G. Interpatient phenotypic inconsistency in severe congenital hemophilia: a systematic review of the role of inherited thrombophilia. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2009;35:307–312. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1222609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Franchini M., Mannucci P.M. Modifiers of clinical phenotype in severe congenital hemophilia. Thromb. Res. 2017;156:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sridharan G., Liu J., Qian K., Goel V., Huang S., Akinc A. In silico modeling of the Impact of antithrombin lowering on thrombin generation in rare bleeding disorders. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):3659. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu J., Qian K., Huang S., Colberg T. Effect of antithrombin lowering on thrombin generation in rare bleeding disorder patient plasma. Haemophilia. 2018;24(Suppl 5) TP-121. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rakhe S., Patel-Hett S.R., Bowley S., Murphy J., Pittman D.D. The tissue factor pathway inhibitor antibody, PF-06741086, increases thrombin generation in rare bleeding disorder and von Willebrand factor deficient plasmas. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):2462. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ott I., Miyagi Y., Miyazaki K., Heeb M.J., Mueller B.M., Rao L.V.M., Ruf W. Reversible regulation of tissue factor-induced coagulation by glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000;20:874–882. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zakai N.A., Lutsey P.L., Folsom A.R., Heckbert S.R., Cushman M. Total tissue factor pathway inhibitor and venous thrombosis. The longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;104:207–212. doi: 10.1160/TH09-10-0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shapiro A.D., Angchaisuksiri P., Astermark J., Benson G., Castaman G., Chowdary P., Eichler H., Jiménez-Yuste V., Kavakli K., Matsushita, et al Subcutaneous concizumab prophylaxis in hemophilia A and hemophilia A/B with inhibitors: phase 2 trial results. Blood. 2019 doi: 10.1182/blood.2019001542. Published online August 23, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eichler H., Angchaisuksiri P., Kavakli K., Knoebl P., Windyga J., Jiménez-Yuste V., Harder Delff P., Chowdary P. Concizumab restores thrombin generation potential in patients with haemophilia: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling results of concizumab phase 1/1b data. Haemophilia. 2019;25:60–66. doi: 10.1111/hae.13627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eichler H., Angchaisuksiri P., Kavakli K., Knoebl P., Windyga J., Jiménez-Yuste V., Hyseni A., Friedrich U., Chowdary P. A randomized trial of safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of concizumab in people with hemophilia A. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018;16:2184–2195. doi: 10.1111/jth.14272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parng C., Singh P., Pittman D.D., Wright K., Leary B., Patel-Hett S., Rakhe S., Stejskal J., Peraza M., Dufield D. Translational Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Characterization and Target-Mediated Drug Disposition Modeling of an Anti-Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor Antibody, PF-06741086. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018;107:1995–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cardinal M., Kantaridis C., Zhu T., Sun P., Pittman D.D., Murphy J.E., Arkin S. A first-in-human study of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of PF-06741086, an anti-tissue factor pathway inhibitor mAb, in healthy volunteers. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018;16:1722–1731. doi: 10.1111/jth.14207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Frenzel A., Schirrmann T., Hust M. Phage display-derived human antibodies in clinical development and therapy. MAbs. 2016;8:1177–1194. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1212149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gu J.-M., Zhao X.-Y., Schwarz T., Schuhmacher J., Baumann A., Ho E., Subramanyan B., Tran K., Myles T., Patel C., Koellnberger M. Mechanistic modeling of the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic relationship of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-neutralizing antibody (BAY 1093884) in cynomolgus monkeys. AAPS J. 2017;19:1186–1195. doi: 10.1208/s12248-017-0086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]