Abstract

Objective

Characterize current practices for pediatric intensive care unit (PICU)-based rehabilitation, and physician perceptions and attitudes, barriers, resources, and outcome assessment in contemporary PICU settings.

Design

International, self-administered, quantitative, cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Online survey distributed March to April 2017.

Patients/Subjects

Pediatric critical care physicians who subscribed to email distribution lists of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators, the Pediatric Neurocritical Care Research Group, or the Prevalence of Acute Critical Neurological Disease in Children: A Global Epidemiological Assessment study group, and visitors to the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies website.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Of the 170 subjects who began the survey, 148 completed it. Of those who completed the optional respondent information, most reported working in an academic medical setting and were located in the United States. The main findings were: (1) a large majority of PICU physicians reported working in institutions with no guidelines for PICU-based rehabilitation, but expressed interest in developing and implementing such guidelines; (2) despite this lack of guidelines, an overwhelming majority of respondents reported that their current practices would involve consultation of multiple rehabilitation services for each case example provided; (3) PICU-physicians believed that additional research evidence is needed to determine efficacy and optimal implementation of PICU-based rehabilitation; (4) PICU-physicians reported significant barriers to implementation of PICU-based rehabilitation across centers; and (5) low routine assessment of long-term functional outcomes of PICU patients, although some centers have developed multidisciplinary follow-up programs.

Conclusions

Physicians lack PICU-based rehabilitation guidelines despite great interest and current practices involving a high degree of PICU-based rehabilitation consultation. Data are needed to identify best practices and necessary resources in the delivery of ICU-based multidisciplinary rehabilitation and long-term functional outcomes assessment to optimize recovery of children and families affected by critical illness.

Keywords: Critical care, Pediatric, Rehabilitation, Outcome, Mobility, Survey, Family-centered

Introduction

Approximately 230,000 children are admitted to pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) at a cost of $8 billion annually in the United States (US) alone.1,2 With the decline in mortality, health systems are recognizing that morbidities affecting physical, emotional, and cognitive health and health-related quality of life are common and need to be addressed to ensure optimal long-term recovery.3–7 Historically, the typical approach to patient activity in the PICU has been bedrest, which is now recognized as an important risk factor for new morbidity.8 Similarly, rehabilitation interventions were typically pursued when the patient was past the critical phase of their illness. Delayed rehabilitation assessment and treatment, however, impedes recovery.9 Recognizing the value of focusing on functioning, PICU-based, multidisciplinary rehabilitation has gained interest as an intervention aimed at improving patient and family functioning.10 The rehabilitation team most often includes physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and speech/language therapy (SLT), but can also include respiratory therapy (RT), behavioral health services, social work, and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians. Recent trials and quality improvement studies in adults with critical illness found that, compared to usual care, early, ICU-based rehabilitative programs improved patient centered outcomes, such as earlier return to independence with activities of daily living, without compromising safety.11

In pediatrics, despite growing clinician and family awareness and interest in PICU-based rehabilitation, there is a paucity of evidence to inform guidelines for patient eligibility, which services to include in a PICU rehabilitation team, optimal timing to initiate rehabilitation, feasibility, safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of such programs. In addition, unlike the call for longitudinal developmental assessment and treatment recommended for premature neonates and infants with congenital heart disease12, there is no such call for assessment of long-term functional outcomes in PICU patients despite research studies highlighting the frequency of often multi-domain, critical illness associated disability.8

Prior to embarking on multi-center PICU-based rehabilitation trials, developing a greater understanding of current PICU-based rehabilitation and outcomes assessment perspectives, usual care practices, and resources in PICUs is essential.13,14 Thus, the aim of the present study was to characterize institutional guidelines and current practices for PICU-based rehabilitation, as well as physician perceptions and attitudes, barriers, resources, and functional outcome assessment in contemporary PICU settings.

Material and Methods

Design

We conducted an international self-administered survey study of pediatric critical care physicians. We used four sources to identify potential respondents: the membership lists of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI; 90 institutions), the Pediatric Neurocritical Care Research Group (PNCRG; 60 institutions across 9 countries), and the Prevalence of Acute Critical Neurological Disease in Children: A Global Epidemiological Assessment study (PANGEA) study group (116 individuals), as well as visitors to the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies (WFPICCS) website (number of visitors unknown). This study was approved as an exempt protocol by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Survey Development

A team of faculty, who represent multiple disciplines that provide care for children with critical illness (e.g., pediatric critical care medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, neuropsychology), used evidence and consensus-based data to develop survey items.15 Two Pediatric Critical Care Medicine faculty at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh who were not involved in the study assessed the comprehensiveness, clarity, and face validity of the survey as well as the administrative ease, flow, and salience of the questions. The survey was then revised based on feedback. We designed clinical case examples representative of patients with common PICU conditions with increased risk of disability to assess current practices for PICU-based rehabilitation consultation and timing of service initiation. The complete survey is provided in the Appendix.

Survey Administration

We emailed an invitation to participate in the survey to the PALISI, PNCRG, and PANGEA email distribution lists in March 2017 with a reminder email in April 2017. The survey was posted on the WFPICCS website during the same period. We used REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Pittsburgh to collect survey responses. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. All responses were anonymous as respondents were identified only by code. As an incentive, we donated 5 US Dollars for each survey completed to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Analyses

We present descriptive statistics as frequencies and percentages, with means (standard deviation [SD]) and 95% confidence intervals where appropriate. For all descriptive analyses, we used the actual number of respondents in the denominator for each item. We collapsed response options where appropriate, to meaningfully summarize responses.

Results

Respondent Data

Of the 170 subjects who began the survey, 148 completed it. Of those who completed the optional respondent information section, 92.6% (50 of 54) reported working in an academic medical setting. Fifty-nine percent (59.3%; 32 of 54) reported working in a free-standing children’s hospital and 79.6% (42 of 54) reported working in the United States. Fifty-three percent (53.3%; 61 of 114) reported providing clinical service within a PICU only, 1.8% (2 of 114) provide clinical service within a pediatric cardiac ICU only, and 44.7% (51 of 114) provide clinical services within both.

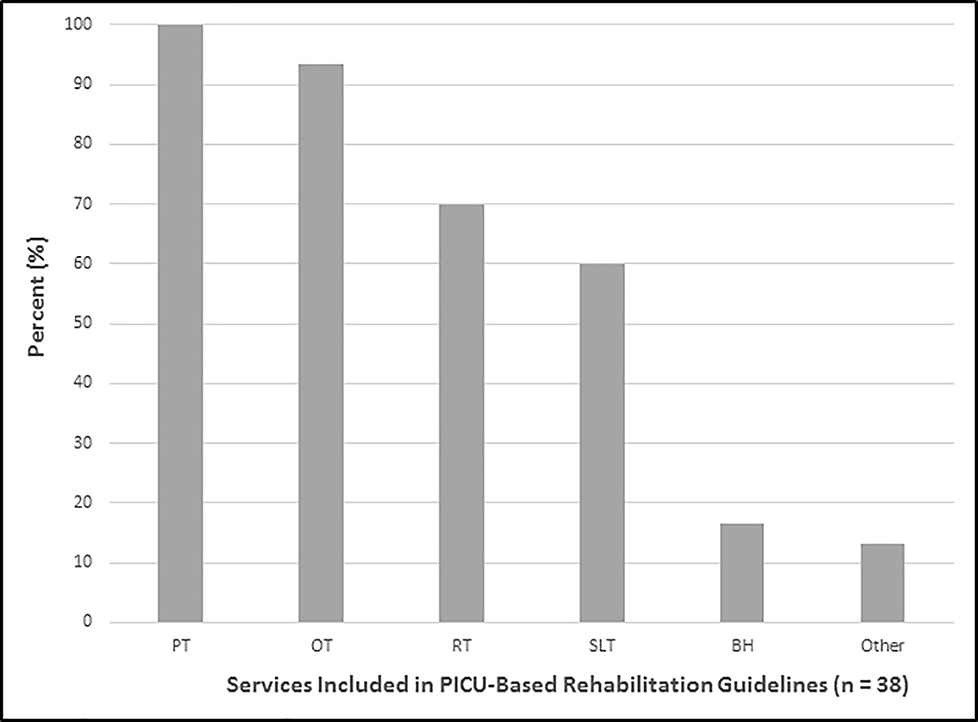

Institutional Guidelines

Seventy-four percent (74.3%; 110/148) of physicians reported that their PICU has no guidelines in place for PICU-based rehabilitation services. Of those with guidelines, 73.7% (28 of 38) reported that guidelines applied to all patients regardless of diagnosis, but 26.3% (10 of 38) reported that the guidelines applied only for specific diagnoses, which included traumatic brain injury (TBI), general trauma, post-operative cardiac surgery, burns, delirium, and other. Figure 1 displays which services are included in the guidelines reported, showing that PT and OT were included in all or almost all guidelines, RT and SLT in the majority, but behavioral health in only 16.7% and other services in 13.3%. Thirty of these 38respondents with guidelines also completed questions about service initiation, with PICU-based rehabilitation service initiation as follows: 13 of 30 within 72 hours of PICU admission; 10 at admission; 3 when the patient was able to cooperate; 2 when the patient was off inotropy-vasopressor support; 1 when the patient was extubated; and 1 when the patient was no longer critically ill and ready for transfer out of PICU. In addition, 6 of 30 respondents reported that their guidelines contained no instructions for initiation of therapies. Regarding mechanism of service initiation of those with guidelines, 20 of 30 required a physician order, 12 an automated computer admission order set, 9 occurred via bedside nurse request, 8 occurred via patient or family request, 1 was automated by unit policy, and 1 occurred via some other mechanism of service initiation.

Figure 1.

Services included in existing PICU-based rehabilitation guidelines. BH = behavioral health; OT = occupational therapy; PT = physical therapy; RT = respiratory therapy; SLT = speech/language therapy

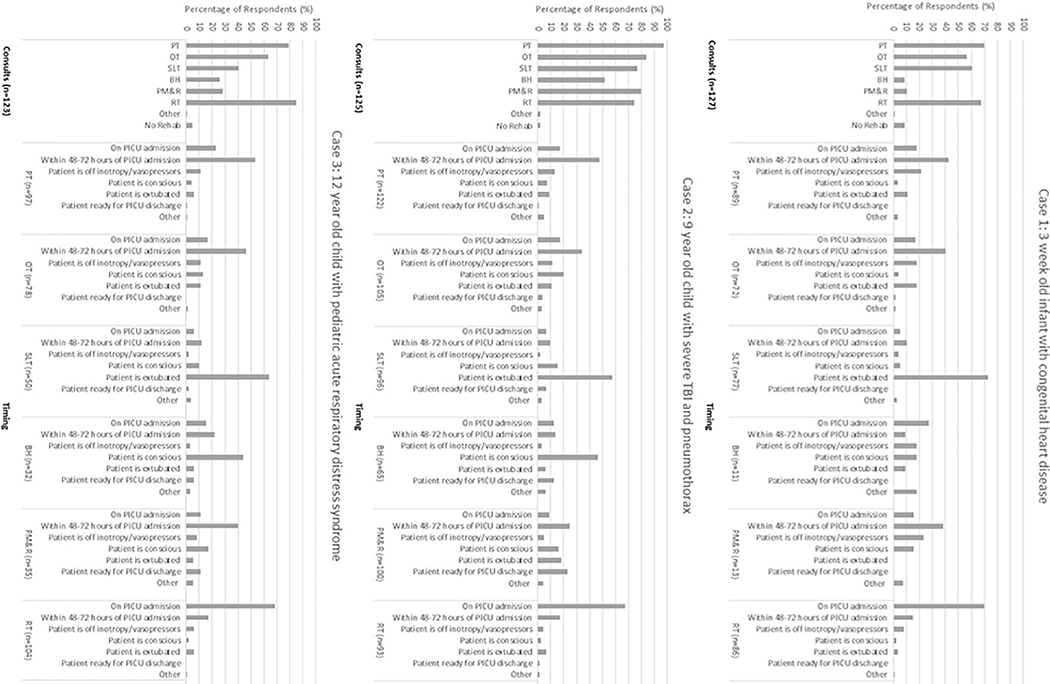

Current Practices for PICU-Based Rehabilitation and Timing of Service Initiation

To evaluate current practices, respondents were asked which PICU-based rehabilitation services they would consult and the timing of initiation recommended in each of three case examples: (Case 1) a 3 week old infant with congenital heart disease; (Case 2) a 9 year old child with severe TBI and pneumothorax; and (Case 3) a 12 year old child with pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS). As shown in Figure 2, an overwhelming majority of respondents reported that their current practices would involve consultation of multiple rehabilitation services in each case, with only 1.6–8.7% of respondents reporting they would not consult any rehabilitation services. PT, OT, and RT were reported as the most consistently consulted rehabilitation services across case examples followed closely by SLT and a lower proportion consulting behavioral health, and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians. Consultation was generally highest across rehabilitation services for the child with TBI and lowest for the infant with congenital heart disease. Regarding timing of consultation initiation, PT and OT consultation was most often initiated within 48–72 hours of PICU admission and SLT consultation was most often initiated once the patient is extubated. Initiation of behavioral health consultation was variable for the infant with congenital heart disease and most often initiated once the patient is conscious for the severe TBI and PARDS cases. Physical medicine and rehabilitation physician consultation was most often initiated within 48–72 hours for the infant with congenital heart disease and the child with PARDS, but more variable for the child with severe TBI. RT consultation was most often initiated at PICU admission across cases.

Figure 2.

PICU-based rehabilitation services consultation and timing of initiation in case examples

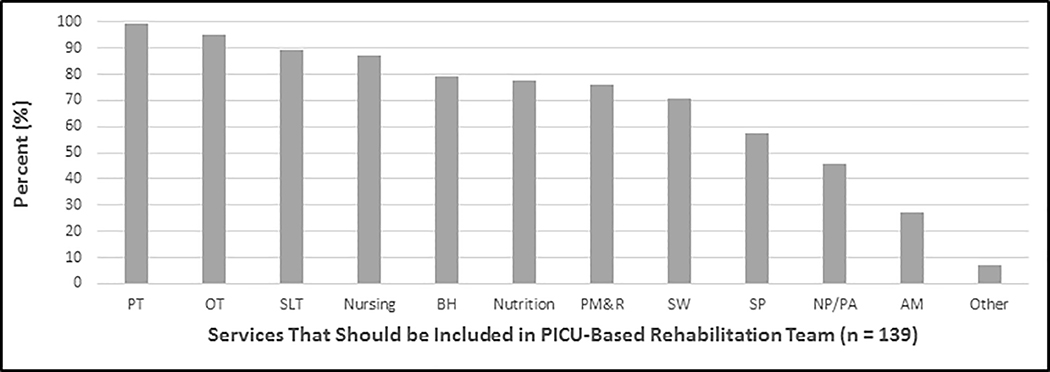

Perceptions and Attitudes

Most respondents believed there is currently “little evidence” (47%; 62 of 132) or “moderate evidence” (37.1%; 49 of 132) to support development of PICU-based rehabilitation guidelines. Most respondents believed it is “very important” (44.7%; 59 of 132) or “important” (34.8%; 46 of 132) to generate evidence using prospective research studies to support evidence-based PICU-based rehabilitation guidelines. Of respondents whose institutions do not currently have PICU-based rehabilitation guidelines, 91.7% (99 of 108) expressed interest in developing and implementing such guidelines. On a Likert scale of 1 “not at all important” to 5 “very important”, respondents (n = 139) believed it was “important” to “very important” to offer the following PICU-based rehabilitation services: PT (4.9); RT (4.7); OT (4.5); SLT (4.4); physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians (4.2); and behavioral health (4.0). Figure 3 shows which services the respondents believed should “ideally make up a PICU rehabilitation team” (n = 131).

Figure 3.

Services respondents believed should ideally make up an PICU-based rehabilitation team. AM = alternative medicine; BH = behavioral health; NP/PA = nurse practitioner/physician assistant; OT = occupational therapy; PM&R = physical medicine & rehabilitation physician; PT = physical therapy; RT = respiratory therapy; SLT = speech/language therapy; SP = supportive/palliative service

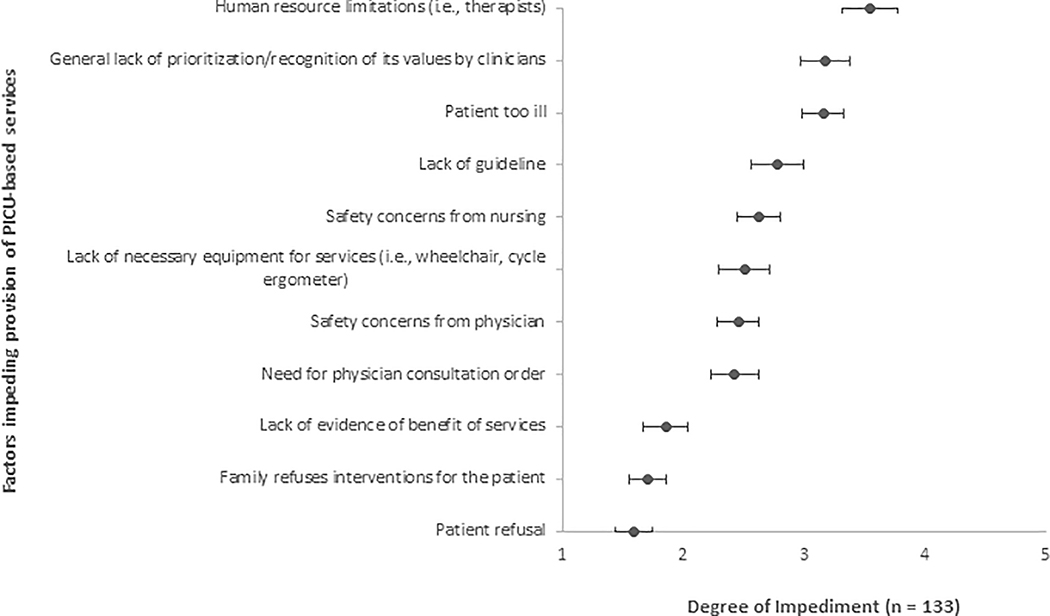

Barriers to Implementation of ICU-Rehabilitation

Figure 4 shows that respondents (n = 133) reported varied factors that impede provision of PICU-based rehabilitation services, with the most commonly reported “significant” to “very significant” barriers including human resource limitations, lack of prioritization by clinicians, patient being too ill, and lack of guidelines.

Figure 4.

Factors impeding provision of PICU-based rehabilitation services.

Rehabilitation Resources Post-Hospital Discharge

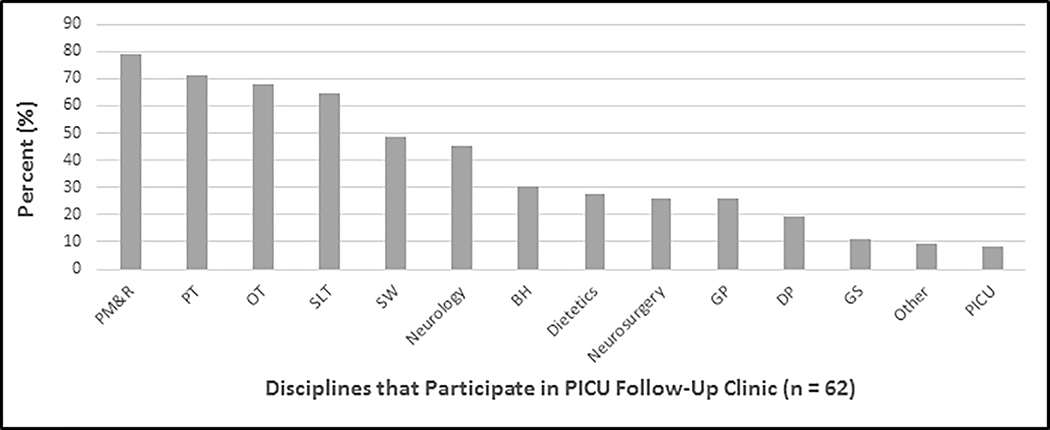

Seventy-three percent (73.3%; 85 of 116) of respondents’ institutions had patient access to a pediatric-specific acute inpatient rehabilitation unit or facility. Of those, 55.3% (47 of 85) of these units/facilities were located in respondents’ hospitals, 42.4% (36 of 85) were located in the local community (within 30 miles), 9.4% (8 of 85) were located in respondents’ referral region but >30 miles, and 4.7% (4 of 85) were located in other areas. A slight majority (53.4%; 62 of 116) of respondents reported that patients from their institution had access to a pediatric-specific outpatient follow-up clinic for the purposes of rehabilitation following PICU discharge. Figure 5 shows that respondents’ (n= 62) follow-up clinics for PICU patients were multidisciplinary, with the majority involving physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, PT, OT, and SLT. Many clinics also involved social work, neurology, behavioral health, dietetics, and general pediatrics.

Figure 5.

Disciplines that participate in PICU Follow-up Clinics. BH = behavioral health; DP = developmental pediatrics; GP = general pediatrics; GS = general surgery; OT = occupational therapy; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; PM&R = physical medicine & rehabilitation physician; PT = physical therapy; RT = respiratory therapy; SLT = speech/language therapy; SW = social work

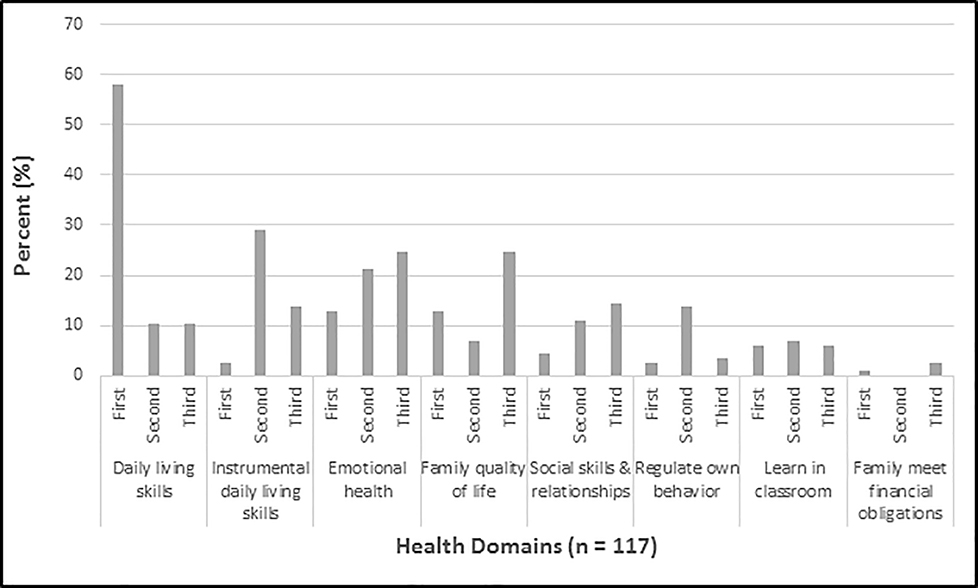

Functional Outcome Assessment

Twenty-two percent (22.8%; 28 of 123) of respondents reported that their PICU performs routine assessment of physical function outcomes. Nine percent (8.9%; 11 of 123) reported routine assessment of quality of life outcomes. Despite the low rates of routine functional outcome assessment, Figure 6 shows the health domains that respondents believed “should be universally assessed and treated to optimize recovery from critical illness, assuming patient survival” (n = 117). The highest-ranking domain was the child’s ability to perform age-appropriate daily living skills (e.g. eating, grooming, dressing). The second highest ranking domain was the child’s ability to manage age-appropriate instrumental daily living skills (e.g. using a phone, making a meal, planning for school activities). Tied for the “third-most important” domain were the child’s emotional health (e.g. anxiety, mood problems, conduct problems) and the family’s quality of life together.

Figure 6.

Health domains that respondents rated as first, second, or third importance that should be universally assessed and treated to optimize recovery from critical illness, assuming patient survival.

Discussion

We performed an international survey of pediatric critical care physicians to characterize current practices and institutional guidelines for PICU-based rehabilitation, perceptions and attitudes, barriers to care, resources, and functional outcome assessment in contemporary PICU settings. The main findings were as follows: (1) a large majority of PICU physicians reported working in institutions with no guidelines for PICU-based rehabilitation, but expressed interest in developing and implementing such guidelines; (2) despite this lack of guidelines, an overwhelming majority of respondents reported that their current practices would involve consultation of multiple rehabilitation services for each case example provided; (3) PICU-physicians believed that additional research evidence is needed to determine efficacy and optimal implementation of PICU-based rehabilitation; (4) PICU-physicians reported significant barriers to implementation of PICU-based rehabilitation across centers; and (5) there is low routine assessment of long-term functional outcomes of PICU patients, although some centers have developed multidisciplinary follow-up programs.

Children with critical illness and their families need innovations to improve functional recovery in addition to traditional organ-based critical care support in the PICU. Contemporary PICU’s have seen dramatic decline in mortality rates with paralleled increased recognition of PICU-related child and family disabilities. Our results demonstrate that our field is at a tipping point at which there is great need and interest among PICU physicians in PICU-based rehabilitation and the development of guidelines for these interventions, yet a similarly great paucity of evidence to inform such guidelines.10 Interestingly, although a large majority of PICU physicians reported working in institutions with no guidelines for PICU-based rehabilitation, an overwhelming majority of respondents reported that their current practices would involve consultation of multiple rehabilitation services for each case example. These findings suggest that PICU-based rehabilitation is already common among current practices but that the evidence and guidelines supporting its use are significantly lagging behind. Our data support a vital need for PICU-based clinical and research programs to support the development of preventative and treatment-based guidelines16 and testing of novel effective therapies to change the status quo from the current predominant focus on survival to a proactive, multiple stakeholder engaged vision of maximizing recovery of the sick child and his or her family. Supporting the ability to investigate and/or implement these approaches, three recent pilot studies have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of PICU-based rehabilitation, with two focused on mobilization therapies and the other on earlier assessment and treatment in neurointensive care patients.17–19

Key perceived barriers to PICU-based rehabilitation identified by our survey included human and equipment resource limitations, lack of prioritization by clinicians, patients being too ill to participate, and lack of guidelines to support clinical practice. These findings, especially those of resource limitations, are consistent with the findings of the feasibility study of Choong and colleagues’17 in which one third of therapy sessions were missed due to limited availability of staff. These findings mirror the reports of adult-based physical therapists.20 These results highlight the “catch 22” of administrators requiring efficacy data to support increasing resources while insufficient resources can hinder research efforts to produce such data. Hopkins et al.21 and Houtrow14 have discussed culture changes and advocacy efforts needed in PICUs to champion the development of PICU-based rehabilitation.

Choong and colleagues22 also reported key institutional barriers, including lack of practice guidelines and the need for physician orders to initiate therapy, as well as conflicting perceptions regarding the clinical thresholds for, and safety of, early mobilization. In our study, institutional guidelines for PICU-based rehabilitation were reported by one quarter of survey respondents and, of those with guidelines, they applied to only selected patient populations. Studies are needed to develop and validate screening criteria to determine which patients and families would benefit from which PICU-based rehabilitative therapies to inform resource needs as it is likely that guideline implementation will increase the stress on resources. Efficacy and safety data and curricula targeted towards PICU providers and caregivers may help overcome cultural and safety concerns to help facilitate delivery of care.21 Finally, most respondents reported that service initiation required a physician order. This is a challenging barrier as physicians are often focused on immediate medical needs rather than longer-term functional outcomes. Some centers reported addressing this issue with an electronic health record trigger for consultation (e.g., > 72 hours after PICU admission). This approach should be studied and/or considered in the context of available resources, as this was a common barrier noted by respondents. For rehabilitation services that are not well resourced or have little evidence-based guideline support in the PICU (e.g. behavioral health, speech and language therapy), development of guidelines to trigger their early involvement may prevent their need from being overlooked by physicians. A lack of consensus regarding both the method and timing of PICU-based rehabilitation service initiation was demonstrated here, with 20% of guidelines lacking any timing specifications. While more data are needed in children, the majority of PICU-rehabilitation studies report no differences in safety with earlier service initiation.19,22–24

Most respondents supported a multidisciplinary approach for PICU-based rehabilitation with a clear focus on patient centered, personalized goals other than mobilization. Service components in respondents with institutional guidelines varied, with PT, OT, and RT among the most common services included, consistent with the existing literature’s focus on non-mobility and mobility interventions.22,25 However, optimal recovery from critical illness is complex and may be better facilitated with a comprehensive – yet ultimately personalized - bundled service.26 For example, despite the growing literature demonstrating significant mental health morbidity for both critically ill children and their families, and a growing body of evidence for effective interventions for these morbidities,27 we found that behavioral health services were rarely included in PICU-based rehabilitation guidelines, would be consulted less than 50% of the time in the case examples, and were included in less than one third of PICU follow-up clinics. Also, it may not be clearly understood by PICU physicians and other providers how services such as SLT (e.g., cognitive, communication, and swallowing) and child life (e.g., play, music therapy, emotional support) can benefit a child’s recovery, yet it is up to clinicians to order consultations to initiate these interventions. One potential method for increasing the involvement of multiple disciplines and rehabilitative services is to conduct multidisciplinary rounds to address these deficits and provide feedback and care coordination on acute and long term functional needs of every PICU patient and family. We have recently initiated this process (Whole Child Rounds) at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, although a formal assessment of the impact of this approach has not yet been carried out.

Three-quarters of respondents reported having access to an acute inpatient rehabilitation facility for children within their hospital or in a nearby community. It is unclear if children in communities without pediatric rehabilitation services would instead attend adult facilities, be prescribed outpatient services, or go without services. More research is needed to better understand inequities in access to rehabilitation and address them with solutions.28,29 Despite recommendations from international societies for institutions to offer long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up for neonates and infants with congenital heart disease,30,31 no recommendations exist for routine assessment of long-term functional outcomes following pediatric critical illness. Remarkably, in this survey, half of respondents reported having outpatient, multidisciplinary follow-up of PICU patients. This finding merits independent confirmation rather than simply being generated via survey. Nevertheless, benefits of follow-up clinics are increasingly being recognized, including screening and referrals for post-traumatic stress syndrome and symptom screening and treatment post-neurocritical illness.32,33 Composition of outpatient-based clinics differed among respondents with a paucity of data to inform ideal disciplines to include to optimize services provided. Challenges to performing patient and family follow-up after critical illness have been identified, including availability of stable funding support, ability to retain family engagement, and lack of multi-stakeholder informed guidelines for optimal implementation.34,35

Finally, less than a quarter of respondents reported that their PICU routinely assessed patient physical function outcomes and less than ten percent reported routine assessment of health-related qualify of life outcomes. Despite this infrequent assessment of functional outcomes, respondents believed the most important outcomes to assess and treat were age-appropriate daily living skills, age-appropriate instrumental daily living skills, emotional health and family’s quality of life together. Ideally, outcomes chosen for standardized assessment would be informed by all stakeholders – patients, families, and clinicians. There is currently no guidance for the assessment of multi-stakeholder informed long-term functional outcomes for clinical or research PICU programs. These findings highlight areas for growth to improve patient satisfaction, and service patient and family needs for recovery.

Overall, these data point to the need for prospective research funding for PICU-based rehabilitation to support evidence-based guidelines and inform clinical resource needs.13,14 Moreover, results support the present as an opportune time to conduct such research while enthusiasm is high but implementation is variable. The present state of affairs allows not only for effectiveness studies to be conducted taking advantage of naturally occurring treatment arms (those who do and do not receive PICU-based rehabilitation intervention as part of clinical care) but also rigorous efficacy studies while it is still considered ethical to randomly assign children to receive or not receive PICU-based rehabilitation services before these services are considered standard of care.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations. An error in the survey design resulted in questions about respondent characteristics, such as institutional setting and country, being optional rather than required and placement of these questions at the end of the survey where they were likely to be missed. As a result, data on these characteristics are missing for more than half of respondents. These missing data have several important implications in interpreting the present results. We are unable to determine with certainty that respondents are representative of the population of pediatric critical care physicians. The majority of respondents who completed the optional respondent characteristic data reported working in an academic medical setting in the US and just over half in a free-standing children’s hospital which is unsurprising given the survey was emailed to members of groups focused on PICU research. We suspect that these respondents may be more disposed to view additional research more favorably and priorities, practices, and resources in academic medical settings might differ from other settings. It is also possible that respondents who chose to complete the survey have particular interest in PICU-based rehabilitation and may not be representative of the general population of pediatric critical care physicians. Due to missing data on respondent country, we are unable to determine how much differences in resources between countries may have influenced the results. Finally, because of the anonymous nature of our survey, some institutions or types of institutions may be over--or under-represented due variability in the number of respondents from each institution, and we did not define the level of the respondents (attending vs. fellow, etc.). Future surveys should also examine the perspectives of practitioners other than critical care physicians, including the multiple disciplines involved in providing PICU-based rehabilitation as well as the perspectives of nursing as well as patients and families. However, given the key role that physician orders play in launching rehabilitation services, we felt that it was essential to focus this survey on PICU physicians. Finally, our approach, although an attempt to include a broad international perspective, did not allow us to define a denominator and thus calculate a response rate for this survey as it was posted on a public website (www.wfpiccs.org) where the number of viewers was unavailable. Based on the broad recruitment strategy, we would have expected more responses overall. Explanations for the relatively low number of responses include: 1) the survey was only available in English; 2) survey fatigue; and 3) physician membership overlap in PALISI, PNCRG, and PANGEA.

Conclusions

Guidelines for PICU-based rehabilitation are lacking in most PICUs despite current practices involving a high degree of PICU-based rehabilitation consultation and great interest in guideline development. The need for PICU-based rehabilitation services and routine long-term functional outcome assessment are strongly supported by PICU physicians, however, multiple barriers exist to their development and implementation. Data are needed to identify best practices and necessary resources in the delivery of ICU-based multidisciplinary rehabilitation and long-term functional outcomes assessment to optimize recovery of children and families affected by critical illness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christopher Horvat, MD, and Dennis Simon, MD, for their feedback on the survey development. We thank Srivatsan Uchani, BA, and Jamie Patronick for their assistance in creating manuscript figures. Thanks to Amy Zhou for her assistance in REDCap survey development.

Funding/Support: Dr. Kochanek receives a stipend from the Society of Critical Care Medicine and World Federation of Pediatric and Intensive Care Societies for his role as editor-in-chief of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (CER-1310-08343) (E.L.F.). Research reported in this manuscript was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CER-1310-08343). The views presented in this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

5T32HD040686-18 (A.T.B.)

Role of the funding source: The funding source (PCORI) had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Interest: This research was supported by Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (CER-1310-08343) (E.L.F.). The remaining authors report no conflicts.

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Beers, Houtrow, Ortiz-Aguayo, Chrisman, Orringer, Smith, and Fink’s institutions received funding from Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Dr. Choong’s institution received funding from Alternate Funding Plan Innovation Grant, and she received funding from McMaster University. Dr. Kochanek received funding from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (stipend for Editor-in-Chief of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine). Dr. Fink’s institution received funding from the National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This project is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02209935)

References

- 1.Randolph AG, Gonzales CA, Cortellini L, Yeh TS. Growth of pediatric intensive care units in the United States from 1995 to 2001. J Pediatr. 2004;144(6):2792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garber N, Watson R, Linde-Zwirble W. The size and scope of intensive care for children in the US. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(S)(A78). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom B, Cohen R a, Freeman G. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health Stat 10 2010;(247):1–82. doi: 10.1037/e609482007-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knoester H, Bronner MB, Bos AP, Grootenhuis MA. Quality of life in children three and nine months after discharge from a paediatric intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran AL, Sharples PM, White C, Knapp M. Time costs of caring for children with severe disabilities compared with caring for children without disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(8):529–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2001.tb00756.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan DP, Rogers ML, Msall ME. Functional limitations and key indicators of well-being in children with disability. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(10):1042–1048. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200104000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Pediatric intensive care outcomes: Development of new morbidities during pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(9):821–827. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: A report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(3):368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tepas JJ, Leaphart CL, Pieper P, et al. The effect of delay in rehabilitation on outcome of severe traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(2):368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuello-Garcia CA, Mai SHC, Simpson R, Al-Harbi S, Choong K. Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Children: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(8):2238–2243. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(9):1143–1172. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fink EL, Houtrow AJ. A new era of personalized rehabilitation in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(6):571–572. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houtrow AJ. Early Rehabilitation: A Path Toward Optimizing Function While Treating Critical Illness in Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(11):1080–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choong K, Koo KKY, Clark H, et al. Early mobilization in critically ill children: a survey of Canadian practice. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(7):1745–1753. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choong K, Canci F, Clark H, et al. Practice Recommendations for Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Children. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2017. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choong K, Awladthani S, Khawaji A, et al. Early Exercise in Critically Ill Youth and Children, a Preliminary Evaluation: The wEECYCLE Pilot Trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(11):e546–e554. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choong K, Chacon MDP, Walker RG, et al. In-Bed Mobilization in Critically Ill Children: A Safety and Feasibility Trial. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2015;4(4):225–234. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fink E, Beers S, Houtrow A, et al. Pilot RCT of early versus usual care rehabilitation in pediatric neurocritical care. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:394. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000528828.59765.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malone D, Ridgeway K, Nordon-Craft A, et al. Physical Therapist Practice in the Intensive Care Unit: Results of a National Survey. Phys Ther. 2015;95(10):1335–1344. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20140417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins R, Choong K, Zebuhr C, Kudchadkar S. Transforming PICU Culture to Facilitate Early Rehabilitation. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2015;04(04):204–211. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choong K, Koo KKY, Clark H, et al. Early mobilization in critically ill children: a survey of Canadian practice. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(7):1745–1753. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wieczorek B, Ascenzi J, Kim Y, et al. PICU Up!: Impact of a Quality Improvement Intervention to Promote Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(12):e599–e566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wieczorek B, Burke C, Al-Harbi A, Kudchadkar SR. Early mobilization in the pediatric intensive care unit: a systematic review. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2015;2015:129–170. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui LR, LaPorte M, Civitello M, et al. Physical and occupational therapy utilization in a pediatric intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2017;40:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning J, Pinto N, Rennick J, Colville G, Curley M. Conceptualizing Post Intensive Care Syndrome in Children-The PICS-p Framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(4):298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.S.C. B, J.A. G. Systematic Review of Interventions to Reduce Psychiatric Morbidity in Parents and Children after PICU Admissions∗. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(4):343–348. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nirula R, Nirula G, Gentilello LM. Inequity of rehabilitation services after traumatic injury. J Trauma - Inj Infect Crit Care. 2009;66(1):255–259. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815ede46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuentes MM, Wang J, Haarbauer-Krupa J, et al. Unmet Rehabilitation Needs After Hospitalization for Traumatic Brain Injury. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20172859. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(9):1143–1172. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barfield WD, Papile L-A, Baley JE, et al. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):587–597. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuel VM, Colville GA, Goodwin S, Ryninks K, Dean S. The value of screening parents for their risk of developing psychological symptoms after PICU: A feasibility study evaluating a pediatric intensive care follow-up clinic. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(9):808–813. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams C, Kirby A, Piantino J. If You Build It, They Will Come: Initial Experience with a Multi-Disciplinary Pediatric Neurocritical Care Follow-Up Clinic. Child. 2017;4(9):pii: E83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bockli K, Andrews B, Pellerite M, Meadow W. Trends and challenges in United States neonatal intensive care units follow-up clinics. J Perinatol. 2014;34(1):71–74. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuppala VS, Tabangin M, Haberman B, Steichen J, Yolton K. Current state of high-risk infant follow-up care in the United States: Results of a national survey of academic follow-up programs. J Perinatol. 2012;32(4):293–298. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.