Abstract

Increasingly many studies have presented robotic simple prostatectomy (RSP) as a surgical treatment option for large benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) weighing 80–100 g or more. In this review, some frequently used RSP techniques are described, along with an analysis of the literature on the efficacy and complications of RSP and differences in treatment results compared with other surgical methods. RSP has the advantage of a short learning curve for surgeons with experience in robotic surgery. Severe complications are rare in patients who undergo RSP, and RSP facilitates the simultaneous treatment of important comorbid diseases such as bladder stones and bladder diverticula. In conclusion, RSP can be recommended as a safe and effective minimally invasive treatment for large BPH.

Keywords: Prostatectomy, Prostatic hyperplasia, Lower urinary tract symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Surgery for large benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) weighing 80–100 g or more poses a major challenge for surgeons. Open simple prostatectomy (OSP), which has been considered the treatment of choice, has a risk of invasiveness and bleeding, and holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP), which has recently been in the spotlight, needs special equipment and has problems with a steep learning curve and transient stress urinary incontinence (SUI) that can remain present for a relatively long time [1-3]. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery—as exemplified by the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)—has been commercialized worldwide, and many institutions are expanding its indications for both malignant and benign diseases. Robotic simple prostatectomy (RSP) can be easily performed by surgeons who have previous experience performing robotic operations in the pelvic cavity [4]. Compared to OSP, it is less invasive, has less bleeding, and can be used to simultaneously treat bladder-related diseases [2,5]. In recent years, as RSP has been performed with increasing frequency, several studies have reported the therapeutic outcomes of RSP as a replacement for OSP. In this paper, we review the history of RSP, along with surgical techniques, indications, effects, and complications. Through a systematic review, we compare RSP with other endoscopic and open surgical techniques to clarify the advantages and disadvantages of RSP. The basic transperitoneal transvesical approach is explained through descriptions, pictures, and video clips to help the readers understand it in a straightforward manner.

HISTORY

Sotelo et al. [6] reported the first results of transperitoneal RSP in 2008 in 7 patients. During a mean operation time of 205 minutes, adenomas weighing on average 50.48 g were removed. Only 1 patient received a blood transfusion, and no other major complications occurred. They argued that RSP is a feasible, reproducible procedure. Later, other practitioners presented early experiences [7-13]. In 2015, results were published from a large European American multicenter study that included 487 cases from 23 institutions [14]. That study analyzed the implementation of RSP in 3-year intervals, with 38 cases between 2006 and 2008, 213 cases between 2009 and 2011, and 237 cases between 2012 and 2014. The authors argued that RSP is a useful surgical procedure at centers where robotic surgery for other diseases is already performed.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The surgical technique of RSP essentially reproduces OSP, with the principal difference being that the basic approach of RSP is transperitoneal. Recently, however, Stolzenburg et al. [15] reported a case of RSP using an extraperitoneal approach. There are 2 ways to resect an adenoma: the transvesical approach and the transcapsular approach. Clavijo et al. [16] reported a case of intrafascial RSP using a technique similar to the radical prostatectomy method that is performed in patients with early prostate cancer.

In this section, we present an overview of the technical details of transperitoneal transvesical RSP, and also briefly describe some modifications. Two supplementary video clips are attached to help to understand the surgical procedure.

Transperitoneal Transvesical Approach

Anesthesia and position

General anesthesia is administered and the patient is placed in the steep Trendelenberg position, as in other robotic pelvic surgical procedures.

Trocar insertion

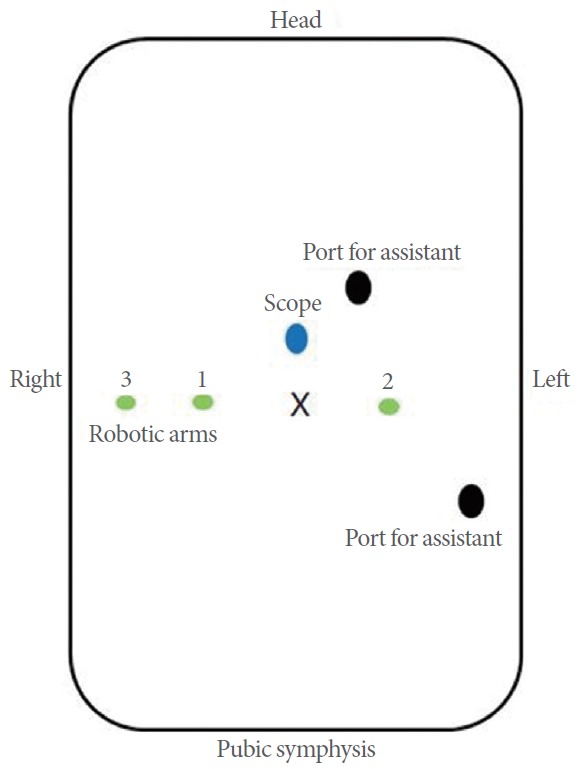

The port configuration is shown in Fig. 1 (with the conventional arrangement of 6 ports, the same as in radical prostatectomy). The 12-mm main camera port is placed through a supraumbilical incision (2–3 cm above the umbilicus). Two 8-mm trocars (1, 2) for robotic instruments are placed 8 cm laterocaudal to the camera port and 15 cm cranial to the pubic symphysis. Another 8-mm trocar (3) for the fourth robotic arm is placed 8 cm lateral to the right-sided robotic port. A 12-mm port for an assistant instrument is placed 8 cm laterocaudal to the left-sided robotic port in a direction pointing toward the anterior superior iliac spine. Another assistant port (12 mm or 5 mm) is placed approximately 8 cm cranial to the midline between the camera port and the left-sided robotic port. In some cases, the fourth robotic arm may be omitted.

Fig. 1.

Configuration of ports for robotic simple prostatectomy.

Bladder dropping and opening of the anterior bladder wall

The bladder is dropped through the conventional Retzius space dissection. Then, the bladder is filled with 100–200 mL of saline and incised transversely or vertically using Hot Shears (Intuitive Surgical) monopolar curved scissors. At this point, some surgeons open the saline-filled bladder directly from the dome without dropping it.

Maximum visibility with bladder wall traction using Monocryl 2-0 sutures

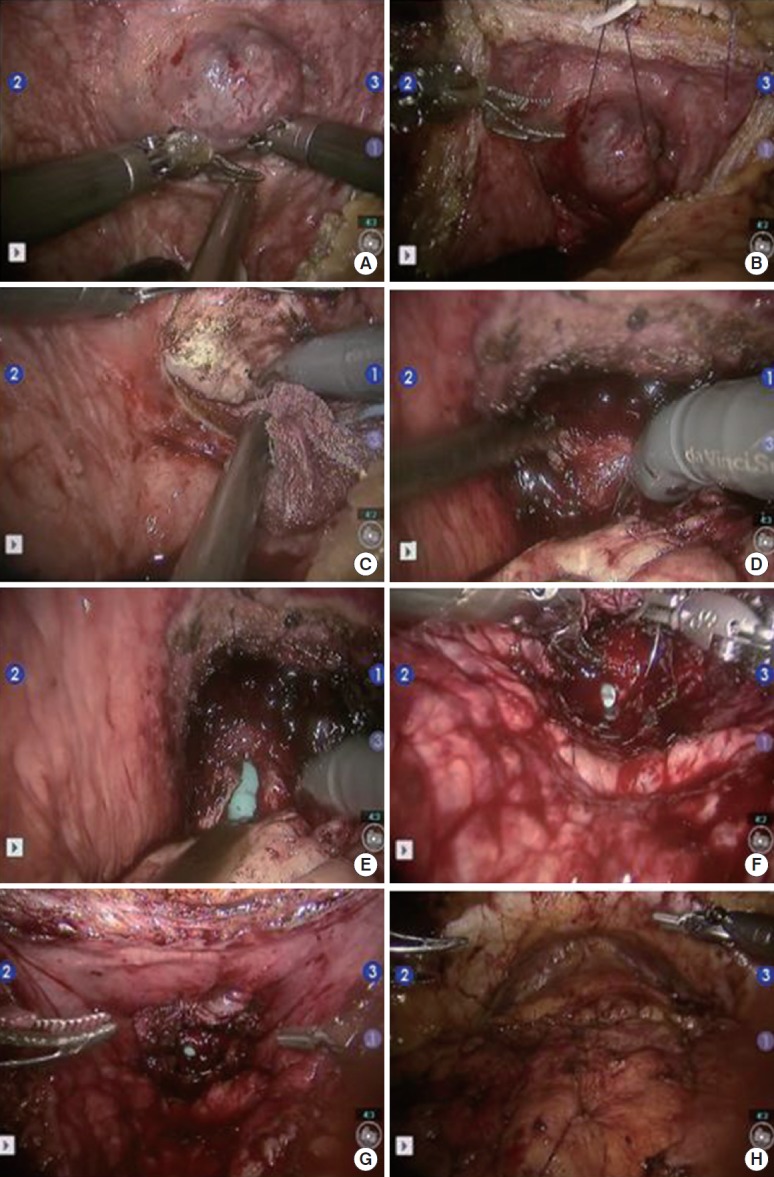

In order to secure the best possible visual field for the operation, both sides of the lower portion of the bladder wall are fixed to the abdominal wall using Monocryl 2-0 sutures, and both ends of the upper portion of the bladder wall are fixed to the fascial tissues of the retroperitoneum (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

Example of a robotic simple prostatectomy procedure. (A) After cystotomy, protrusion of a prostatic adenoma into the bladder was found. (B) Retraction sutures on the adenoma facilitated enucleation. (C) Dissection was performed between the adenoma and prostatic parenchyma. (D) After the dissection was complete, the urethra could be cut under direct vision. (E) After cutting the urethra, the Foley catheter could be seen. (F) Shape of the prostatic fossa after removal of the adenoma. (G) Capsular plication and bladder neck reconstruction. (H) Closure of cystotomy.

Incision on the bladder mucosa covering the protruding adenoma

The position of the ureteric orifices is identified to ensure safety during resection, and an initial incision is made over the adenoma in the 6-o’clock position to find the correct plane between the adenoma and the peripheral zone of the gland (surgical capsule). This incision should not be too shallow (Fig. 2C).

Dissection between the adenoma and prostatic parenchyma

This plane is developed bluntly and sharply in a circumferential direction on both sides of the prostate with careful hemostasis using monopolar and bipolar coagulation. Monocryl 2-0 stay stitches are used to provide traction on the adenoma to assist dissection. The fourth robot arm or an assistant’s aid can be used to pull the adenoma. The dissection proceeds from the base to the apex and is carried out as far distally as possible without risking injury to the external sphincter mechanism. In the 12-o’clock direction, particular care should be taken, remembering that the length of adenomas along the midline is shorter than in other directions.

Apical dissection

At the apex, adenoma dissection should proceed with appropriate consideration of the fact that more lateral adenoma tissue may be present distal to the adenoma-urethral junction of the midline. The principle is not to transect the adenoma, but to remove the entire adenoma along the margin. Once the dissection is complete, the urethra can be cut under direct vision. However, it is not always possible to incise the urethra under clear vision. In such cases, the urethra is cut in the 12-o’clock direction first, the adenoma is removed from the attachment, and the remaining tissues are trimmed (Fig. 2D, E).

Bleeding control of the prostatic fossa

Bleeding vessels in the prostatic bed are coagulated and may be oversewn with a 3-0 V-Loc (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) running suture (Fig. 2F).

Bladder neck reconstruction

Bladder neck–reconstructing sutures incorporating the prostate tissue and bladder mucosa are done circumferentially with a 2-0 V-Loc (Covidien) continuous running suture, which is helpful for hemostasis. Some surgeons perform retrigonization by advancing the bladder neck mucosa as far distally to the prostate apex as possible (Fig. 2G).

Bladder closure

A 20F three-way Foley catheter is placed and the cystotomy is closed in 2 layers using 3-0 and 2-0 V-Loc sutures. Irrigation with normal saline is continued overnight (Fig. 2H).

Other Modifications

Transperitoneal transcapsular approach (the Millin technique)

A transverse incision is made through the prostate capsule. The adenoma is identified via electrocautery of the prostate capsule through the superficial dorsal venous complex. Using a combination of blunt dissection and electrocautery to obtain hemostasis, the adenoma is dissected circumferentially. The urethra is incised distally. The adenoma is removed and the bladder neck mucosa is then advanced to the urethral mucosa with 2-0 Monocryl interrupted sutures [13].

Extraperitoneal approach

The preperitoneal space is prepared with finger dissection and balloon insufflation.

After all trocars are inserted, a cystotomy incision is made longitudinally from the anterior bladder wall to the bladder neck, and the adenoma is removed in a similar way as in the transperitoneal approach [15].

Intrafascial simple prostatectomy

This procedure, reported by Clavijo et al. [16] is similar to the radical prostatectomy technique that is performed in patients with low-risk localized prostate cancer. In the early stages of surgery, the neurovascular bundles are fully saved in the intrafascial layer, the prostate pedicle and deep dorsal vein complex are divided and secured, the urethra is cut, the seminal vesicle and vas deferens are cut at the prostate base and then closed, and finally urethrovesical anastomosis is performed. The authors emphasized that this technique offers several advantages. First, it eliminates the need for irrigation, as there is no bleeding of the prostatic fossa. Second, it is favorable for detecting prostate cancer and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Third, it prevents the development of prostate cancer or new prostate enlargement after surgery because it removes all prostate tissue.

Single-port suprapubic transvesical simple prostatectomy

Steinberg et al. [17] reported a series of 10 extraperitoneal RSPs performed using the da Vinci SP surgical system. A single surgeon with extensive experience in RSP operated via the extraperitoneal and transvesical routes through the robotic cannula of the da Vinci SP system. The mean estimated blood loss was 141±98 mL and the operation time was 172±19 minutes. The mean catheter time was 1.9±1.8 days.

RESULTS OF RSP: EFFICACY AND COMPLICATIONS

Literature Review

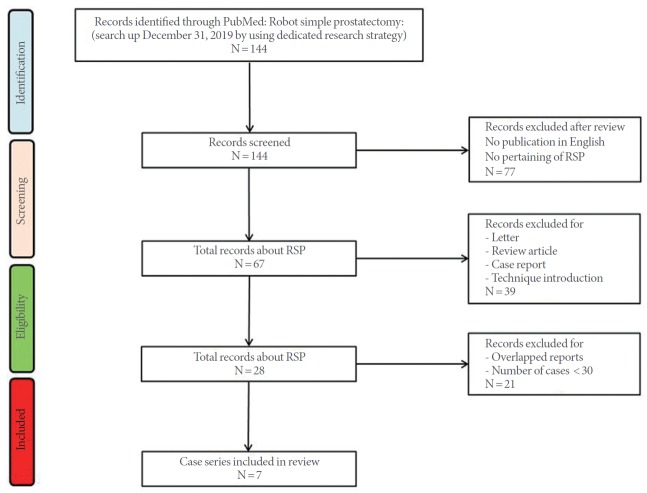

PubMed was searched for “robot simple prostatectomy” or “robotic simple prostatectomy.” Of the 144 papers, 77 were not directly related to RSP or were not written in English. Review articles, expert opinions, case reports, and letters were excluded, resulting in 30 remaining full-text articles. After the exclusion of series describing fewer than 30 cases and studies with data from more than 5 institutions, 7 case series were analyzed (Fig. 3). Four series were comparative studies and remaining 3 series were noncomparative studies [3,4,18-22]. One series analyzed and reported the results of 2 different RSP techniques separately [19]. That review also presented the results of the separate analysis (Table 1). The total number of patients at the 7 institutions was 574, and the mean age of the patients was 68.4 years. The operation time was 97–274 minutes. The Foley catheter indwelling duration was 3–9.4 days and the mean weight of the removed prostate adenoma was 82.7 g (range, 61.2–110 g). Blood transfusion was performed in 0%–9.4% of patients, and major complications occurred in 1.2%–7.5% of cases. Regarding functional outcomes, patients showed significant improvements in maximum flow rate and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) at postoperative follow-up examinations. The 3 series reported incidental prostate cancer rates of 0.8%–11% [3,19,20].

Fig. 3.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram. RSP, robotic simple prostatectomy.

Table 1.

Characteristics and perioperative outcomes of the included studies

| Year of publication |

2012 |

2015 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Matei et al. [4] | Pokorny et al. [18] | Martín Garzón et al. [19] | Martín Garzón et al. [19] | Pavan et al. [20] | Zhang et al. [21] | Johnson et al. [3] | Nestler et al. [22] |

| No. of patients | 35 | 67 | 79 | 76 | 130 | 32 | 12 | 35 |

| No. of surgeons | - | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 or more | 2 | 2 | |

| Age (yr) | 65.5 | 69 | 69.5 | 64.5 | 67.4 | 71 | 70 | 70.9 |

| Mean operative time (min) | 186 | 97 | - | - | 150 | 274 | 157 | 182 |

| Estimate blood loss (mL) or Hemoglobin change | 121 mL | 200 mL | 390 mL | 535 mL | 250 mL | -2.5 g/dL | -5.4 % | -1.5 g/dL |

| Duration of Foley catheter indwelling (day) | 7.4 | 3 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| Hospitalization period (day) | 3.17 | 4 | - | - | 5 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| preoperative PSA (mg/dL) | 5.44 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 10 | 6.1 | 6.4 | ||

| Preoperative prostate volume (g) | 106.6 | 129 | 80.3 | 75.5 | 118.5 | 121.5 | 94.5 | |

| Resection volume (g) | 87.04 | 84 | - | - | 77 | 110 | 61.2 | 77 |

| Preoperative IPSS | 28 | 25 | 22.7 | 20.9 | 23 | - | - | 23 |

| Postoperative IPSS | 7 | 3 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 5 | - | - | - |

| Transfusion rate (%) | 0 | 1.5 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 9.4 | 3.3 | 9.4 | |

| Surgical route | Transvesical | - | Millin (retropubic) | Intrafascial | Trans and extraperitoneal | - | - | - |

| Major complication rate (%) | - | 4.5 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 7.5 | - |

| Participation center (single or multi) | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | - |

| Comparable study | - | - | vs. LSP | vs. LSP | vs. LSP | vs. HoLEP | Learning curve | vs. OSP, ThuVEP |

| Cancer detection rate (%) | - | - | 5.06 | 26 | 0.8 | - | 11 | - |

IPSS, International Prostate symptom Score; LSP, laparoscopic simple prostatectomy; OSP, open simple prostatectomy; HoLEP, holmium laser enucleation of the prostate; ThuVEP, thulium vapoenucleation of the prostate.

Comparative Studies

The surgical outcomes were compared with pure laparoscopic surgery in 2 series. Martín Garzón et al. [19] compared the results obtained using 2 robotic techniques with the results of pure laparoscopy. Intrafascial RSP was safe and effective, and a 1-year follow-up showed that incontinence, IPSS, and Sexual Health Inventory for Men scores were comparable to those of patients who underwent pure laparoscopic or traditional RSP. In another study comparing the results of 189 cases of pure laparoscopy and 130 cases of RSP, the predicted bleeding volume was slightly higher in the LSP group (300 mL vs. 350 mL, P=0.07), but both procedures were found to be safe and effective, with no significant differences between them [20]. Studies have also compared RSP with OSP, thulium vapoenucleation of the prostate (ThuVEP), and HoLEP. Nestler et al. [22] compared the results of 35 RSP procedures with those of 35 OSP and 35 ThuVEP procedures in a matched-pair analysis of the databases of 3 institutions. The operation time was 130 minutes, 83 minutes, and 182 minutes for OSP, ThuVEP, and RSP, respectively, with the longest time found in the robot series. The transfusion rate was 34.4%, 0%, and 9.4%, respectively. Postoperative improvements in uroflow and symptom scores were good in all 3 groups, with no major difference. They concluded that robotic surgery offers a reasonable alternative approach to open procedures, with the only significant disadvantage being operation time. Zhang et al. [21] compared the perioperative outcomes of 600 patients who underwent HoLEP performed by 6 surgeons at one institution and 32 patients who underwent RSP performed by 2 surgeons at another institution. The amount of tissue removed was 96 g and 110 g, respectively; more tissue was removed in the RSP group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.15). Furthermore, the rate of complications of Clavien grade 3 or greater (P=0.03) was not significantly different between the 2 groups. The operation time was significantly longer in the RSP group (103 minutes vs. 274 minutes, P<0.001). The decrease in hemoglobin levels (1.8 g/dL vs. 2.5 g/dL), the transfusion rate (1.8% vs. 9.4%), hospital stay (1.3 days vs. 2.3 days), and the mean duration of catheterization (0.7 days vs. 8 days) were superior in the HoLEP group. The operation time for the RSP group was markedly longer than at other institutions because the study included 2 patients with a prostate size of more than 200 g.

DISCUSSION

The use of RSP in the surgical treatment of large BPH (weighing 80–100 g or more) has certain advantages over OSP, including a reduced bleeding volume, lower transfusion rate, and faster recovery. Compared with pure laparoscopy, it shows comparable surgical results, but it has the advantages of reducing fatigue and being easy to perform for the surgeon. The operation time of RSP is still inferior to that of other procedures. However, considering that reports on other comparators such as HoLEP presented results from the most experienced surgeons, further improvements in the operation time of RSP are expected, since we are still in the early reporting stage.

The learning curve of RSP is relatively short, at 10–12 cases [3]. In particular, surgeons with experience in robotic pelvic surgery can perform the operation without any difficulty, because the pelvic anatomy is already familiar, and there is a low risk of requiring transfusion or experiencing major perioperative complications, even for beginners. In contrast, according to Brunckhorst et al. [23], the learning curve of HoLEP is about 50 cases, and complications occur in roughly 20% of the first 40 cases.

RSP has the advantage of sparing the urethra during the surgical procedure, which requires a long time in the case of massive BPH. However, HoLEP requires the use of a 26F sheath, so surgery may not be easy in patients with a small-caliber urethra. In addition, removing massive BPH through the urethra presents a risk of urethral damage and resulting urethral stricture. In transurethral resection of the prostate, the incidence of postoperative urethral stricture has generally been reported to be approximately 6.5%, and in HoLEP, urethral stricture was reported in approximately 3.3% of second procedures [24,25]. In contrast, urethral stricture rarely occurs in RSP.

In RSP, adenoma is removed by pulling it in the opposite direction, without damaging the external sphincter or tissues associated with the continence mechanism such as the endopelvic fascia or puboprostatic ligament. Therefore, there is little worry about incontinence after RSP and no reports have described incontinence as a complication of RSP. For HoLEP, transient incontinence occurs in approximately 22% of cases. According to Cho et al. [26], 18 patients, 4.6% of 393 patients who underwent HoLEP experienced urinary incontinence for longer than 3 months. The factors involved in urinary incontinence were transition zone prostate volume and the enucleation ratio. Shigemura et al. [27] also analyzed the result of 203 HoLEP operations. According to their report, postoperative SUI was present at 1, 3, and 6 months in 35 (29.4%), 20 (16.8%), and 6 patients (5.04%), respectively, who underwent surgery performed by beginner surgeons, and in 32 (38.1%), 11 (13.1%), and 4 patients (4.76%), respectively, who were treated by experienced surgeons. Approximately 5% of patients experienced urinary incontinence for more than 6 months, suggesting that SUI during this period can cause significant stress and anxiety, diminishing the patient’s quality of life.

RSP has the advantage of enabling simultaneous surgery for associated diseases that are often present in patients with giant BPH, such as bladder stones, bladder diverticula, and inguinal hernia. These conditions can be corrected at the same time without having to make separate incisions or change the position.

CONCLUSIONS

As a form of surgical treatment in patients with large BPH, RSP has the advantage of a short learning curve for surgeons with experience in robotic surgery and a lower risk of major complications because of the good visual field. Since RSP is not performed through the urethra, the risk of urethral injury or stricture is lower than for transurethral procedures, which require hour-long manipulations of the urethra in patients with large prostates. RSP can be done in patients who cannot be placed in the lithotomy position and in patients with a narrow meatus, and it enables simultaneous surgery for important comorbid diseases such as bladder stones and bladder diverticula.

The time spent on RSP varies depending on the operator, but there is substantial room to reduce the operation time depending on the surgeon’s experience. In the future, surgical robots are expected to be adopted for most urological operations. Robotic surgery will be a very useful modality for most urosurgeons; therefore, RSP is expected to be very widely adopted and performed by more operators for the treatment of large BPH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

· Conceptualization: TKY

· Data curation: TKY

· Formal analysis: JMC, KTM, TKY

· Methodology: JMC, TKY

· Project administration: TKY

· Visualization: JMC, KTM, TKY

· Writing - original draft: JMC, KTM

· Writing - review & editing: JMC, KTM, TKY

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary video clips 1 and 2 can be found via https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2040018.009.v1 and https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2040018.009.v2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Foster HE, Dahm P, Kohler TS, Lerner LB, Parsons JK, Wilt TJ, et al. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA Guideline Amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202:592–8. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cockrell R, Lee DI. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy: expanding on an established operative approach. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18:37. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0681-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson B, Sorokin I, Singla N, Roehrborn C, Gahan JC. Determining the learning curve for robot-assisted simple prostatectomy in surgeons familiar with robotic surgery. J Endourol. 2018;32:865–70. doi: 10.1089/end.2018.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matei DV, Brescia A, Mazzoleni F, Spinelli M, Musi G, Melegari S, et al. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP): does it make sense? BJU Int. 2012;110(11 Pt C):E972–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magera JS, Jr, Adam Childs M, Frank I. Robot-assisted laparoscopic transvesical diverticulectomy and simple prostatectomy. J Robot Surg. 2008;2:205–8. doi: 10.1007/s11701-008-0100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sotelo R, Clavijo R, Carmona O, Garcia A, Banda E, Miranda M, et al. Robotic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;179:513–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ou R, You M, Tang P, Chen H, Deng X, Xie K. A randomized trial of transvesical prostatectomy versus transurethral resection of the prostate for prostate greater than 80 mL. Urology. 2010;76:958–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John H, Bucher C, Engel N, Fischer B, Fehr JL. Preperitoneal robotic prostate adenomectomy. Urology. 2009;73:811–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutherland DE, Perez DS, Weeks DC. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy for severe benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol. 2011;25:641–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uffort EE, Jensen JC. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic simple prostatectomy: an alternative minimal invasive approach for prostate adenoma. J Robot Surg. 2010;4:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s11701-010-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vora A, Mittal S, Hwang J, Bandi G. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy: multi-institutional outcomes for glands larger than 100 grams. J Endourol. 2012;26:499–502. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuh B, Laungani R, Perlmutter A, Eun D, Peabody JO, Mohler JL, et al. Robot-assisted Millin’s retropubic prostatectomy: case series. Can J Urol. 2008;15:4101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banapour P, Patel N, Kane CJ, Cohen SA, Parsons JK. Robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy: a systematic review and report of a single institution case series. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:1–5. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Autorino R, Zargar H, Mariano MB, Sanchez-Salas R, Sotelo RJ, Chlosta PL, et al. Perioperative outcomes of robotic and laparoscopic simple prostatectomy: a European-American multi-institutional analysis. Eur Urol. 2015;68:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stolzenburg JU, Kallidonis P, Kyriazis I, Kotsiris D, Ntasiotis P, Liatsikos EN. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy by an extraperitoneal approach. J Endourol. 2018;32(S1):S39–43. doi: 10.1089/end.2017.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clavijo R, Carmona O, De Andrade R, Garza R, Fernandez G, Sotelo R. Robot-assisted intrafascial simple prostatectomy: novel technique. J Endourol. 2013;27:328–32. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinberg RL, Passoni N, Garbens A, Johnson BA, Gahan JC. Initial experience with extraperitoneal robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy using the da Vinci SP surgical system. J Robot Surg. 2019 Sep 27; doi: 10.1007/s11701-019-01029-7. [Epub]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pokorny M, Novara G, Geurts N, Dovey Z, De Groote R, Ploumidis A, et al. Robot-assisted simple prostatectomy for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic enlargement: surgical technique and outcomes in a high-volume robotic centre. Eur Urol. 2015;68:451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martín Garzón OD, Azhar RA, Brunacci L, Ramirez-Troche NE, Medina Navarro L, Hernández LC, et al. One-year outcome comparison of laparoscopic, robotic, and robotic intrafascial simple prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol. 2016;30:312–8. doi: 10.1089/end.2015.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavan N, Zargar H, Sanchez-Salas R, Castillo O, Celia A, Gallo G, et al. Robot-assisted versus standard laparoscopy for simple prostatectomy: multicenter comparative outcomes. Urology. 2016;91:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang MW, El Tayeb MM, Borofsky MS, Dauw CA, Wagner KR, Lowry PS, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between holmium laser enucleation of the prostate and robot-assisted simple prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2017;31:847–50. doi: 10.1089/end.2017.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nestler S, Bach T, Herrmann T, Jutzi S, Roos FC, Hampel C, et al. Surgical treatment of large volume prostates: a matched pair analysis comparing the open, endoscopic (ThuVEP) and robotic approach. World J Urol. 2019;37:1927–31. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2585-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunckhorst O, Ahmed K, Nehikhare O, Marra G, Challacombe B, Popert R. Evaluation of the learning curve for holmium laser enucleation of the prostate using multiple outcome measures. Urology. 2015;86:824–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol. 1989;141:243–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marien T, Kadihasanoglu M, Tangpaitoon T, York N, Blackburne AT, Abdul-Muhsin H, et al. Outcomes of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate in the re-treatment setting. J Urol. 2017;197:1517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.12.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho KJ, Koh JS, Choi JB, Kim JC. Factors associated with early recovery of stress urinary incontinence following holmium laser enucleation of the prostate in patients with benign prostatic enlargement. Int Neurourol J. 2018;22:200–5. doi: 10.5213/inj.1836092.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shigemura K, Tanaka K, Yamamichi F, Chiba K, Fujisawa M. Comparison of predictive factors for postoperative incontinence of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate by the surgeons’ experience during learning curve. Int Neurourol J. 2016;20:59–68. doi: 10.5213/inj.1630396.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.