Abstract

Totipotency refers to the ability of a cell to generate all of the cell types of an organism. Unlike pluripotency, the establishment of totipotency is poorly understood. In mouse embryonic stem cells, Dux drives a small percentage of cells into a totipotent state by expressing 2-cell-embryo-specific transcripts. To understand how this transition takes place, we performed single-cell RNA-seq, which revealed a two-step transcriptional reprogramming process characterized by downregulation of pluripotent genes in the first step and upregulation of the 2-cell-embryo-specific elements in the second step. To identify factors controlling the transition, we performed a CRISPR–Cas9-mediated screen, which revealed Myc and Dnmt1 as two factors preventing the transition. Mechanistic studies demonstrate that Myc prevents downregulation of pluripotent genes in the first step, while Dnmt1 impedes 2-cell-embryo-specific gene activation in the second step. Collectively, the findings of our study reveal insights into the establishment and regulation of the totipotent state in mouse embryonic stem cells.

Following fertilization, the mouse genome starts to be activated at late 1-cell and 2-cell stages. This process is known as zygotic genome activation1, and coincides with a gain of totipotency, the ability of a cell to generate embryonic and extraembryonic cell types2. Interestingly, a group of genes (for example, Zscan4 genes) and repeats (for example, MERVL repeats) are transiently activated at this stage3,4, suggesting their role in establishing totipotency2. However, the molecular features of totipotency remained elusive partly due to the scarcity of mammalian embryos.

The mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) derived or cultured under modified conditions exhibit totipotent-like developmental potential5–7, but these cells are transcriptionally distinct from 2-cell embryos. Interestingly, in serum/leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) culture conditions, <1% of mESCs exhibit several features of 2-cell embryos4,8, including expression of 2-cell-embryo-specific transcripts4, downregulation of pluripotency genes4, increased histone mobility9, dispersed chromocentres10 and increased developmental capacity4. This spontaneous 2-cell-like (2C-like) state is reversible, and nearly all mESCs are capable of cycling between ESC and 2C-like states4. Compared with 2-cell embryos, which are difficult to obtain in large numbers, 2C-like cells can be readily isolated from ESCs, making them a good model for understanding totipotency and zygotic genome activation11. While several factors, such as Tet proteins, were reported to regulate the formation of 2C-like cells12–14, a detailed mechanistic understanding of the 2C-like transition is still lacking, partially due to the low frequency of 2C-like cells in mESCs. The demonstration that Dux can drive the ESC to 2C-like cell transition15–17 makes the generation of 2C-like cells much easier. In this study, we examine the transcriptional dynamics of the 2C-like transition using Dux and identify factors mediating the transition process.

Results

Establishment and verification of a Dux-mediated ESC to 2C-like transition system.

We constructed an ESC line containing a MERVL-promoter-driven tdTomato transgene (an indicator of the 2C-like state)4 and a doxycycline-inducible Dux transgene (Fig. 1a). Dux expression induces the 2C-like transition (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Depending on the ESC clones, the 2C-like transition rates varied between 10 and 55%, which is comparable to previous reports16. The 2C-like transition rate is regulated by the exogenous Dux level as the clones with higher Dux expression exhibited a higher rate of 2C-like transition (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). The fact that not all cells became 2C-like cells after Dux induction suggests cell-to-cell heterogeneity (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a).

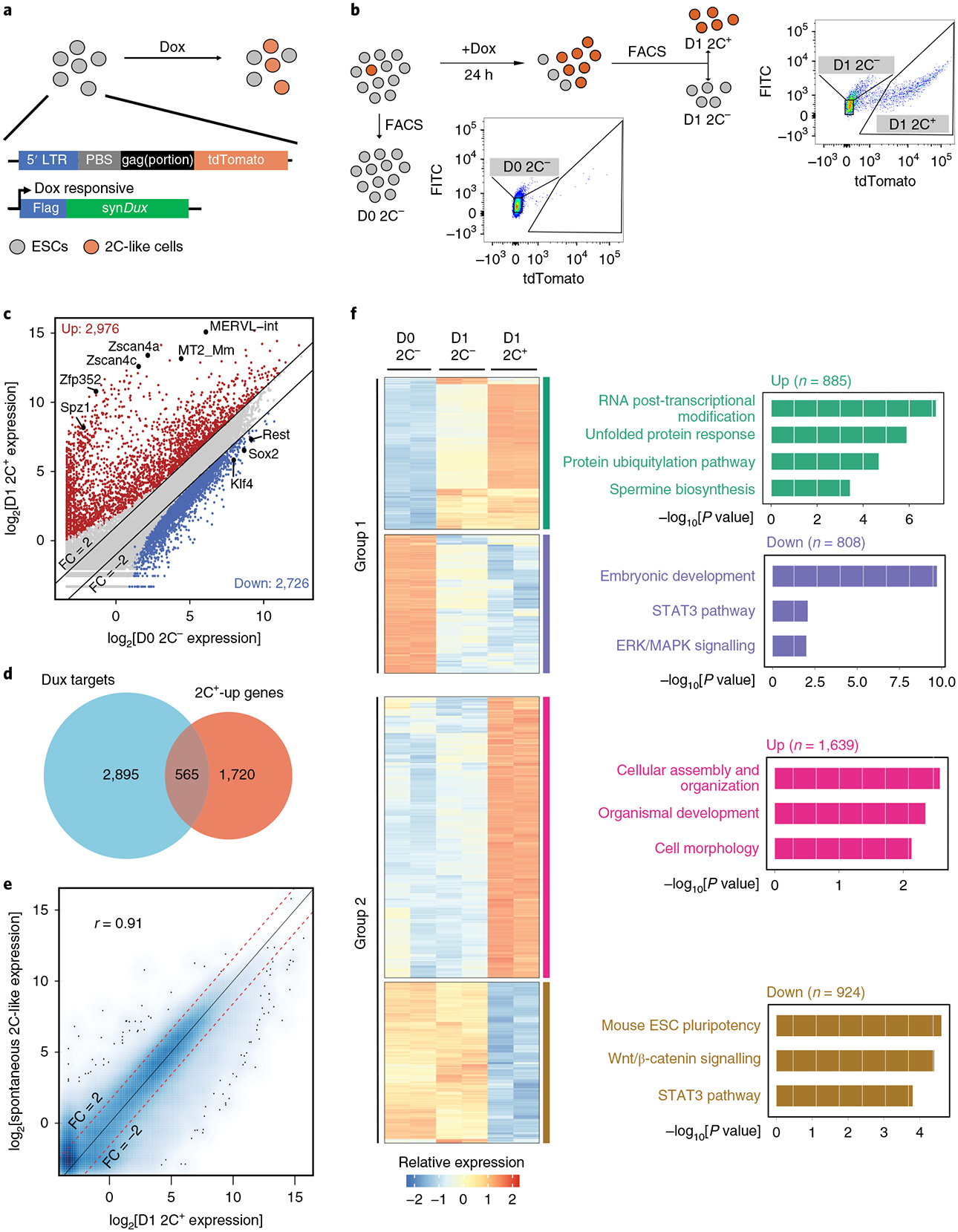

Fig. 1 |. RNA-seq indicates a step-wise pattern of transcriptome reprogramming from ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

a, A schematic representation of the constructs in the reporter cell line. tdTomato is under the control of the MERVL promoter. synDux refers to codon-optimized exogenous Dux. PBS, primer-binding site. LTR, long terminal repeats. b, A diagrammatic representation of the different cell populations and the FACS threshold for cell isolation. c, A scatter plot comparing the gene/repeat expression profiles between D0 2C− (ESCs) and D1 2C+ (2C-like cells) populations (n = 32,831). The criteria for gene changes are FC > 2 and FDR < 0.001. FDRs were estimated using the Benjamini-Hochberg method on the P values of the two-sided quasi-likelihood F-test calculated using the edgeR package37. d, A Venn diagram between Dux-bound genes in ESCs and genes upregulated in D1 2C+ cells. e, A scatter plot comparing the gene expression profiles between spontaneous 2C-like cells and Dux-induced 2C-like cells (Pearson correlation, r = 0.91, n = 27,220). f, A heatmap showing the relative expression levels of group 1 and group 2 genes from 2 biologically independent samples of D0 2C−, D1 2C− and D1 2C+ cell populations (left) and the −log10[P value] of the gene ontology (GO) terms enriched in each category of genes (right, right-tailed Fisher’s exact test). The number of genes in each category is indicated at the top of each GO enrichment plot (right). b-f were summarized from two independent replicates of RNA-seq experiments (n refers to the number of transcribed genes/repeats). Statistical source data can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

To characterize the transcriptomic change of the Dux-induced 2C-like transition, we performed RNA-seq analysis of three cell populations: a 2C-negative population collected before Dux-induction (D0 2C−), and 2C-negative and 2C-positive populations collected after 1 d Dux induction (D1 2C− and D1 2C+) (Fig. 1b).

By comparing the transcriptome of ESCs (D0 2C−)to that of 2C-like cells (D1 2C+), we identified 2,976 upregulated and 2,726 downregulated genes/repeats in 2C-like cells (fold change (FC) > 2, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.001; Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). The 2C+-upregulated genes/repeats include 2-cell-embryo-specific transcripts such as MERVL repeats, Zscan4 genes, Spz1 and Zfp352 (Fig. 1c) and are involved in chromatin and nucleosome assembly (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The downregulated genes include pluripotency-related genes such as Sox2, Klf4 and Rest (Fig. 1c) and are involved in organic anion transport and development (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Analysis of published Dux chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data in mESCs16 indicated that many of the genes upregulated in 2C+ cells are direct targets of Dux (Fig. 1d). Notably, the transcription start sites (TSSs) of upregulated genes are significantly closer to MERVL repeats than those with unchanged or downregulated genes (Supplementary Fig. 1e). This indicates that 2C+-upregulated genes could be activated by nearby MERVL repeats, which is similar to that observed in spontaneous 2C-like cells4,18.

Importantly, the transcriptome and expression pattern of 2-cell-embryo-specific elements (D1 2C+ cells) are highly similar to those of spontaneous 2C-like cells (Pearson r=0.91, Fig. 1e; Pearson r=0.9, Supplementary Fig. 1f). In addition, the apoptosis-related genes that are induced by Dux in C2C12 are not increased in D1 2C+ cells (Supplementary Table l)19. Furthermore, similarly to spontaneous 2C-like cells, Dux-induced 2C-like cells can exit the 2C-like state spontaneously (Supplementary Fig. 1g,h). Taken together, these results suggest that we established a 2C-like transition system that resembles the spontaneous 2C-like transition.

Dux-induced ESC to 2C-like cell transition involves an intermediate state.

Since Dux did not induce a complete 2C-like transition (Fig. 1b), we characterized the molecular features of D1 2C− cells by comparing their transcriptome to those of other cell populations (D0 2C− and D1 2C+). Despite a negative tdTomato signal, D1 2C− cells displayed a partial change in many of the 2C+ up/downregulated elements. The genes/repeats whose expression levels are altered in both D1 2C− and D1 2C+ cells are designated as ‘group 1’ elements (Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 1f). In group 1, the downregulated genes are enriched for terms of embryonic development and signalling pathways important for pluripotency (Fig. 1f), while the upregulated genes are enriched for terms of RNA modification and protein unfolding (Fig. 1f). Interestingly, another group of genes/repeats (group 2 elements) are significantly altered only in D1 2C+ cells (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Table 2), with the downregulated genes involved in mECS pluripotency, and upregulated genes involved in cellular assembly and organization. Most of the activated repeats belong to the late-altered group 2 elements (Supplementary Fig. 1i), which is consistent with activation of the MERVL reporter in D1 2C+ cells. Taken together, D1 2C− cells exhibited an intermediate-state transcriptome different from the starting ESCs (Supplementary Fig. 1j).

The distinct expression patterns of group 1 and group 2 elements imply that transcriptional reprogramming during the pluripotent to 2C-like transition may follow a sequential order. Group 1 elements might be changed first followed by the alteration of group 2 elements. Consistent with this notion, a majority of Dux-bound 2C+-upregulated genes belong to group 1 genes, while group 2 genes dominate the 2C+-upregulated genes (Supplementary Fig. 1k), suggesting that Dux-bound genes get activated first during the transition.

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis confirmed the existence of an intermediate state.

To further confirm the intermediate state during the transition, we performed single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) at different time points of Dux induction (Fig. 2a). Consistent with the timing of tdTomato reporter activation (Supplementary Fig. 1a), MERVL and Zscan4 are activated in many cells only after 1 d Dux induction (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

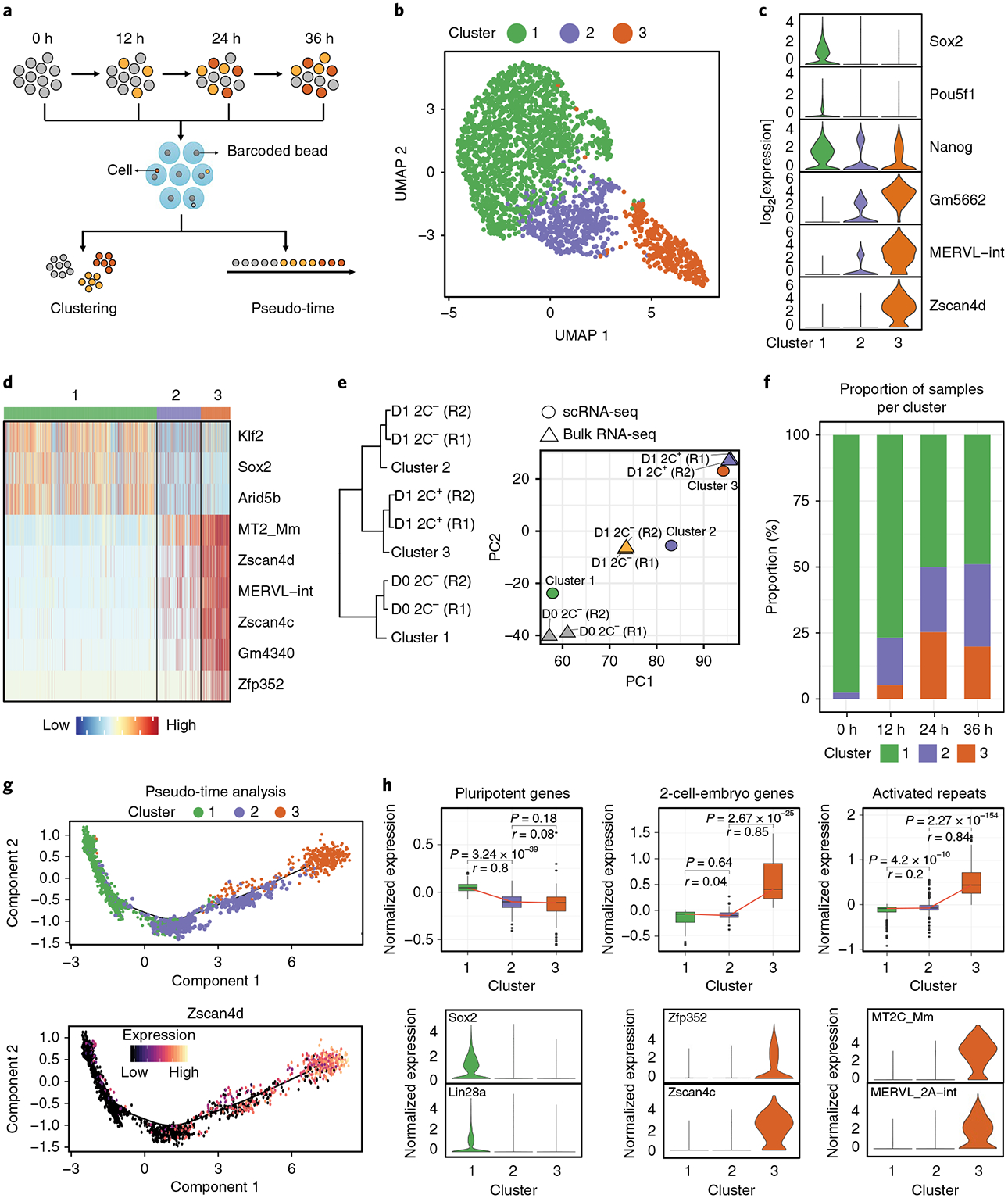

Fig. 2 |. scRNA-seq reveals a transcriptional roadmap of the ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

a, Workflow of scRNA-seq. Totals of 738, 456, 568 and 871 cells at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h and 36 h of Dux induction were collected. b, A uniform manifold approximation and projection representation (UMAP) of cells sequenced by Drop-seq. Cluster 1 (1,780 cells), Cluster 2 (512 cells), Cluster 3 (341 cells). c, A violin plot showing the log2 expression of representative genes in each cluster (n = 1,780 cells, 512 cells and 341 cells respectively for clusters 1, 2 and 3). d, A heatmap showing the normalized expression of marker genes in each cluster. e, Hierarchical clustering (complete linkage) and PCA analysis of the relationship between single-cell clusters (n = 3 clusters) and FACS-isolated cell populations (n = 6 biologically independent cell populations isolated by FACS) based on the transcriptional profiles of commonly expressed genes/repeats (n = 18,373 genes/repeats). R1/2, replicate 1/2. f, A bar plot showing the proportion of the different cell clusters at different time points of Dux induction. On Dux induction, an increased proportion of cells transit into the intermediate or 2C-like state. g, Scatter plots showing cells along the projected pseudo-time (top panel) and Zscan4d expression following the dynamics of the ESC to 2C-like cell transition. h, Top: box plots showing the expression of 2C+-downregulated pluripotent genes (n = 135 genes), 2C+-upregulated 2-cell-embryo-specific genes (n = 75 genes) and activated repeats (n = 501 repeats) in each cell cluster. The black central line is the median, the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles, the whiskers indicate the 1.5 interquartile range and dots represent outliers. P values were calculated by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests and effect sizes (shown as r) were calculated as , where Z is the Z value of the Mann–Whitney U-test and N is the number of samples. Bottom: violin plots showing the expression of representative genes and repeats in each cell cluster (n = 1,780, 512 and 341 cells, respectively, for clusters 1, 2 and 3). The violin plots in c,h show the kernel density estimation of the distribution of the gene expression in each cluster. The width of the plot represents the proportion of data with the corresponding expression value. Statistical source data can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

Due to cellular heterogeneity, we pooled all of the cells to perform clustering analysis, which revealed three major cell clusters (Fig. 2b–d). Cluster 3 appears to be 2C-like cells with expression of Zscan4 and MERVL (Fig. 2b–d and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Cluster 1 represents ESCs as they express pluripotency genes such as Sox2 and Pou5f1, but not MERVL and Zscan4 (Fig. 2b–d). Cluster 2 represents an intermediate cell population as they showed a reduced expression of pluripotency genes such as Sox2 and Pou5f1, and also a partial expression of 2-cell-embryo-specific transcripts such as MERVL and Gm5662 (Fig. 2b–d and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Interestingly, Nanog messenger RNA is not decreased during the transition (Fig. 2c).

Previous single-cell studies identified a minor formative-state pluripotent population in mESCs20–22. We identified a similar minor population (Supplementary Fig. 2c), with low expression of Zfp42, Klf4, and Nanog, but high expression of Pou3f1, Dnmt3b, and Krt18 compared to that of the major pluripotent cells (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis confirmed the existence of this minor population in mESCs (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Identification of this minor formative state in mESC validates our scRNA-seq approach.

To determine the relationship between the single-cell populations and the bulk RNA-seq stages (Fig. 1b), we performed clustering and principal component analysis (PCA). Indeed, the transcriptional profiles of the three cell clusters respectively correlate with D0 2C−, D1 2C− and D1 2C+ cell populations (Fig. 2e). Thus, scRNA-seq data can be used to analyse the transcriptional dynamics during the 2C-like transition. Consistently, analysis of the distribution of the different cell clusters at each time point revealed that the Dux-induced 2C-like transition is recapitulated by scRNA-seq (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2f). Taking these findings together, we conclude that scRNA-seq revealed an intermediate cell state during the 2C-like transition. Notably, although D1 2C− cells consisted of ~66% cluster 1 cells (Fig. 2f), activation of 2C+-upregulated elements in D1 2C− cells (Fig. 1f) dominated the transcriptional variance in PCA analysis leading to a higher correlation of D1 2C− cells with cluster 2 cells rather than cluster 1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2g).

scRNA-seq confirmed a two-step transcriptional reprogramming of the ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

The identification of an intermediate state indicates that the 2C-like transition follows a step-wise pattern. To dissect the transcriptional dynamics during the 2C-like transition, we performed pseudo-time analysis (Fig. 2g). The projected timeline recapitulated the 2C-like transition as it captured the progressive activation of 2C-like-cell markers such as Zscan4d (Fig. 2g). The pseudo-time indicates that cluster 1 (pluripotent ESCs) cells are mainly at the beginning of the projected timeline trajectory. Cluster 2 cells are mainly located in the middle of the timeline, whereas cluster 3 (2C-like) cells are at the end of the timeline (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 3a). The distribution of cells from different time points along the pseudo-time also captures the Dux-induced 2C-like transition (Supplementary Fig. 3b), supporting the validity of the projected timeline. In addition, many group 1 genes, including Zscan4d, Dppa2 and Chd5, are altered in cluster 2 cells, while group 2 genes, such as Slc35e3, Fbxo34 and Socs2, tend to be altered in cluster 3 cells, further supporting the validity of the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Together, the findings of the scRNA-seq analysis provided a transcriptomic roadmap for the 2C-like transition.

Bulk RNA-seq revealed that the 2C-like transition involved the downregulation of pluripotency genes and the expression of 2-cell-embryo-specific elements (Fig. 1c). To dissect the temporal dynamics of these alterations, we analysed the expression pattern of these elements in scRNA-seq. We found that downregulation of pluripotency-related genes has already occurred in the intermediate state, while the activation of 2-cell-specific elements was not evident until the 2C-like state (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 3d,e). Notably, bulk RNA-seq based on the MERVL reporter cannot distinguish intermediate cells from pluripotent cells, and thus failed to reveal the temporal order of downregulation of pluripotent genes and upregulation of 2-cell-specific elements during the 2C-like transition (Fig. 1f). Collectively, our results support that the pluripotent to totipotent state transition is achieved in two steps: the pluripotent to intermediate state, characterized by downregulation of pluripotency genes; and the intermediate to 2C-like cell state, characterized by the activation of 2-cell-embryo-specific genes and repeats.

Identification of regulators for the ESC to 2C-like cell transition by CRISPR–Cas9 screening.

The incomplete 2C-like transition after Dux induction indicates the existence of barriers preventing the transition. To identify these barriers, we performed a screen utilizing a previously reported CRISPR–Cas9 library23. After 1 d Dux induction, 2C+ and 2C− cells were sorted for sequencing to determine the relative single guide RNA (sgRNA) enrichment. The sgRNA of positive regulators will be depleted from the 2C+ population, and vice versa (Fig. 3a). As a control for experimental variation, two independent screens were performed and gene enrichment/depletion was ranked using the MAGeCK package24.

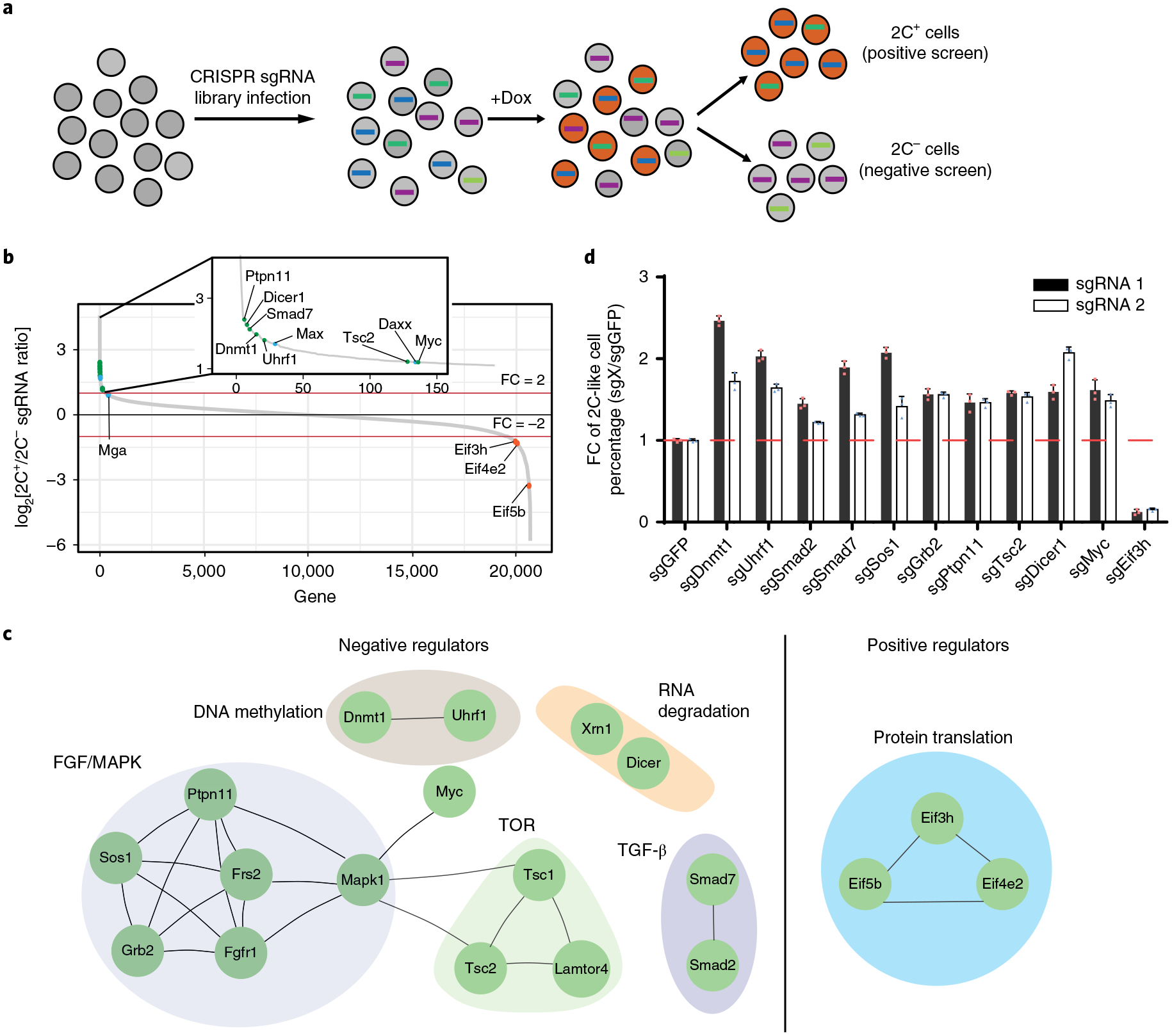

Fig. 3 |. CRISPR–Cas9 screening identified regulators mediating the ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

a, A schematic of the CRISPR–Cas9 screen. Two biologically independent screens were performed. b, The sgRNA count enrichment from the first screen replicate. Notably, several known negative regulators, such as Daxx, Max and Mga, were also identified in the screen, supporting the validity of our screen. The green dots indicate inhibitors identified by this screen, the orange dots indicate positive regulators identified by this screen, and the blue dots indicate known regulators. c, The interaction network of the top candidates identified from the screen. d, The fold change (FC) of the 2C-like cells relative to the sgGFP control after 1 d Dux induction. The X in sgX refers to the gene that sgRNA targets to. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples. The experiment was repeated independently twice with similar results. The source data can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

The screen identified reproducible negative regulators (positive robust rank aggregation score <0.01; Supplementary Table 4), including Dnmt1, Uhrf1, Ptpn11, Dicer1, Smad7, Myc and Tsc2 (Fig. 3b, green dots, Supplementary Fig. 4a) and reproducible positive regulators (negative robust rank aggregation score <0.01; Supplementary Table 4) of the 2C-like-state transition, such as Eif3h, Eif5b and Eif4e2 (Fig. 3b, orange dots, Supplementary Fig. 4b). To identify potential pathways regulating the 2C-like transition, we performed a protein interaction analysis on reproducible hits and identified multiple networks for negative regulators, including Dnmt1/Uhrf1 for DNA methylation, Grb2/Ptpn11/Sos1 of the MAPK signalling pathway and Tsc1/Tsc2 of the TOR signalling pathway (Fig. 3c), supporting the validity of the screen. This analysis also identified Eif3h/Eif5b/Eif4e2 involved in translation as a network of positive regulators (Fig. 3c).

To validate the roles of these identified regulators in the 2C-like-state transition, we picked 11 candidate regulators based on the interaction analysis. For each candidate, we performed CRISPR gene perturbation and quantified 2C-like cells after Dux induction. Perturbation of all ten negative candidates increased 2C-like cells, while perturbation of Eif3h reduced 2C-like cells (Fig. 3d). These results further validate our screen results. Since our study focuses on transcriptional regulation of the 2C-like transition, we focus on Myc and Dnmt1 to understand how they negatively regulate the transition process.

Myc prevents gene downregulation during the ESC to intermediate-state transition.

Myc is a transcription factor critical for the pluripotent transcriptome25. Interestingly, the 2C-like transition involves transcriptomic reprogramming (Fig. 1c) and Myc is one of the top candidates regulating the transition (Fig. 3b). To understand how Myc regulates this process, we designed two sgRNAs targeting Myc and confirmed their efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Myc depletion increased the 2C-like cells in three different ESC clones on Dux induction (Fig. 4a). Notably, sgMyc exhibited no effect on 2C-like-state maintenance (Supplementary Fig. 5b), indicating that Myc deficiency increased 2C-like cells by facilitating the 2C-like transition. The effect of Myc on the 2C-like transition is independent of Dux expression, as Myc depletion did not alter Dux expression (Fig. 4b). In addition, Myc deficiency facilitated the spontaneous 2C-like transition (Supplementary Fig. 5c), indicating that the effect of Myc on the transition is not dependent on the Dux transgene.

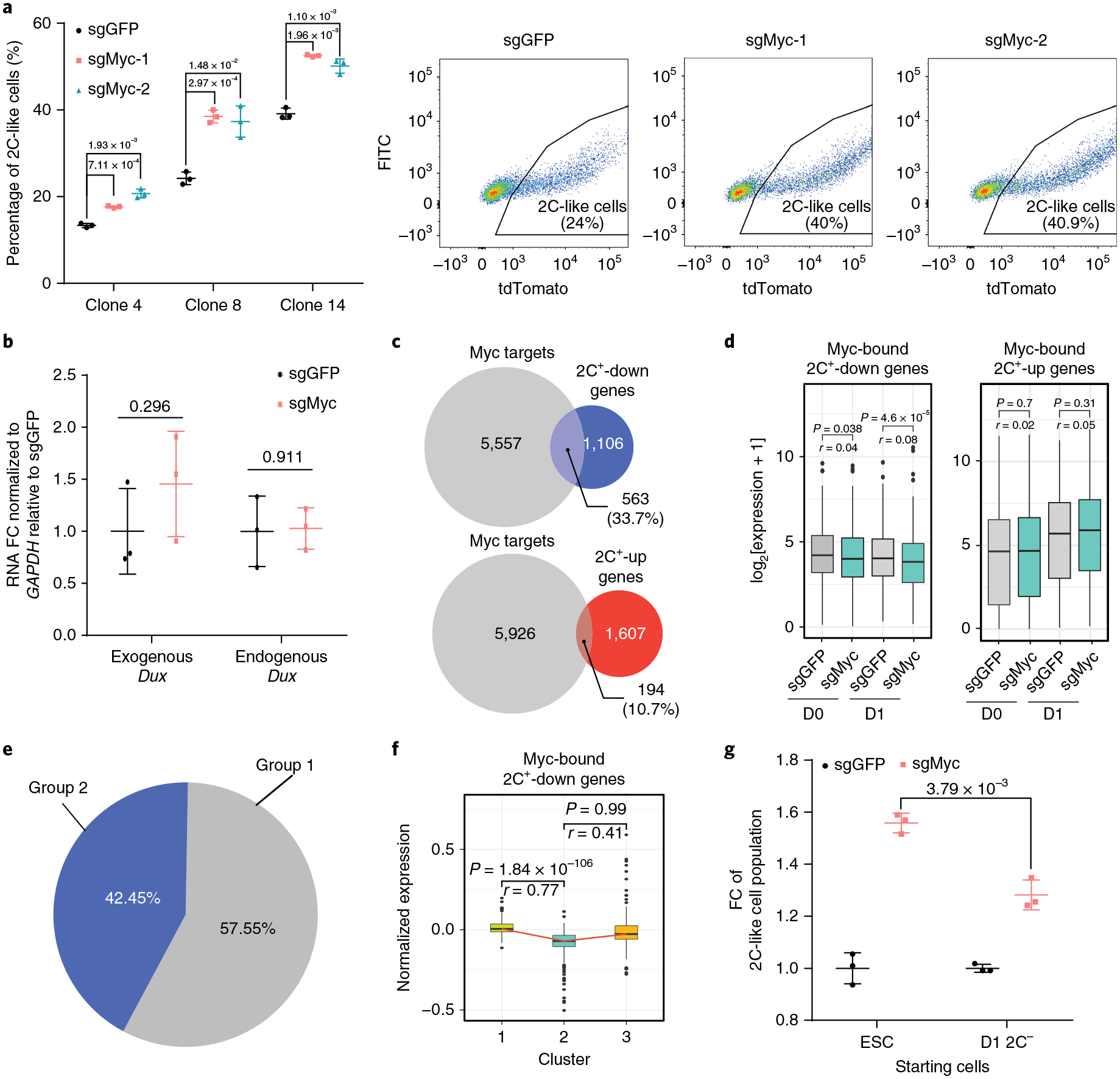

Fig. 4 |. Myc impedes the repression of 2C+-downregulated genes at the early stage of the ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

a, The percentage of 2C-like cells after 1 d Dux induction of the indicated manipulation in three independent ESC clones and representative FACS from clone 8. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. b, The relative expression (quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (qRT-PCR)) of endogenous and exogenous Dux normalized to Gapdh after 1 d induction. FC, fold change. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. c, A Venn diagram of Myc-bound genes in ESCs overlapped with 2C+-upregulated and -downregulated genes, respectively. d, The expression levels of Myc-bound 2C+- downregulated genes (n = 1,059 genes) and 2C+-upregulated genes (n = 194 genes). e, A pie chart showing the relative percentage of group 1 and group 2 genes in Myc-bound 2C+-downregulated genes. f, A box plot showing the log2 expression in each cell cluster of Myc-bound 2C+-downregulated genes detected in single-cell data (n = 408 genes). g, The fold change (FC) of the 2C-like cell population after 1 d Dux induction in sgMyc relative to the sgGFP control. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. In a,b,g, the P values (indicated as numbers in the graphs) were calculated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, two-sample unequal variance. The experiments were repeated independently twice with similar results. In d,f, the black central line is the median, the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles, the whiskers indicate the 1.5 interquartile range and the dots represent outliers. P values were calculated by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests and effect sizes (shown as r) were calculated as , where Z is the Z value of the Mann–Whitney U-test and N is the number of samples. d-f were based on two independent replicates of RNA-seq experiments. Statistical source data can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

Myc maintains the pluripotent transcriptome by amplifying the transcription of a large set of genes (Supplementary Fig. 5d)26,27. As the ESC transcriptome is reprogrammed during the 2C-like transition, we asked whether Myc impedes the transition by preventing transcriptional reprogramming. To this end, we focused on the direct Myc targets in ESCs28 and found that 33.7% of 2C+-downregulated genes are Myc targets (Fig. 4c). In contrast, only 10.7% of 2C+-upregulated genes are Myc targets (Fig. 4c), suggesting that Myc mainly antagonizes gene downregulation during the transition. Indeed, Myc-bound 2C+-downregulated genes were further decreased in Myc-depleted cells after Dux induction, while the expression of Myc-bound 2C+-upregulated genes was not affected (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 5), indicating that Myc inhibits the 2C-like transition by preferably maintaining the expression of 2C+-downregulated genes in ESCs.

Transcriptome analysis revealed that downregulation of pluripotency genes mainly occurs at the ESC to intermediate-state transition (Fig. 2h). Since Myc amplifies the transcriptional activity of 2C+-downregulated pluripotent genes27,29,30, we asked whether Myc mainly prevents the ESC to intermediate-state transition. To this end, we analysed the Myc-bound 2C+-downregulated genes (Fig. 4c) and found that the majority of these genes belong to group 1 genes (Fig. 4e). Downregulation of these genes mainly takes place during the ESC to intermediate-state transition (Fig. 4f), suggesting that Myc impedes their downregulation at the early stage of the 2C-like transition. Consistently, Myc deficiency in ESCs has a bigger effect on the 2C-like transition than that in D1 2C−cells, which displayed an intermediate transcriptome (Fig. 4g). Thus, we conclude that Myc mainly impedes the ESC to intermediate-state transition.

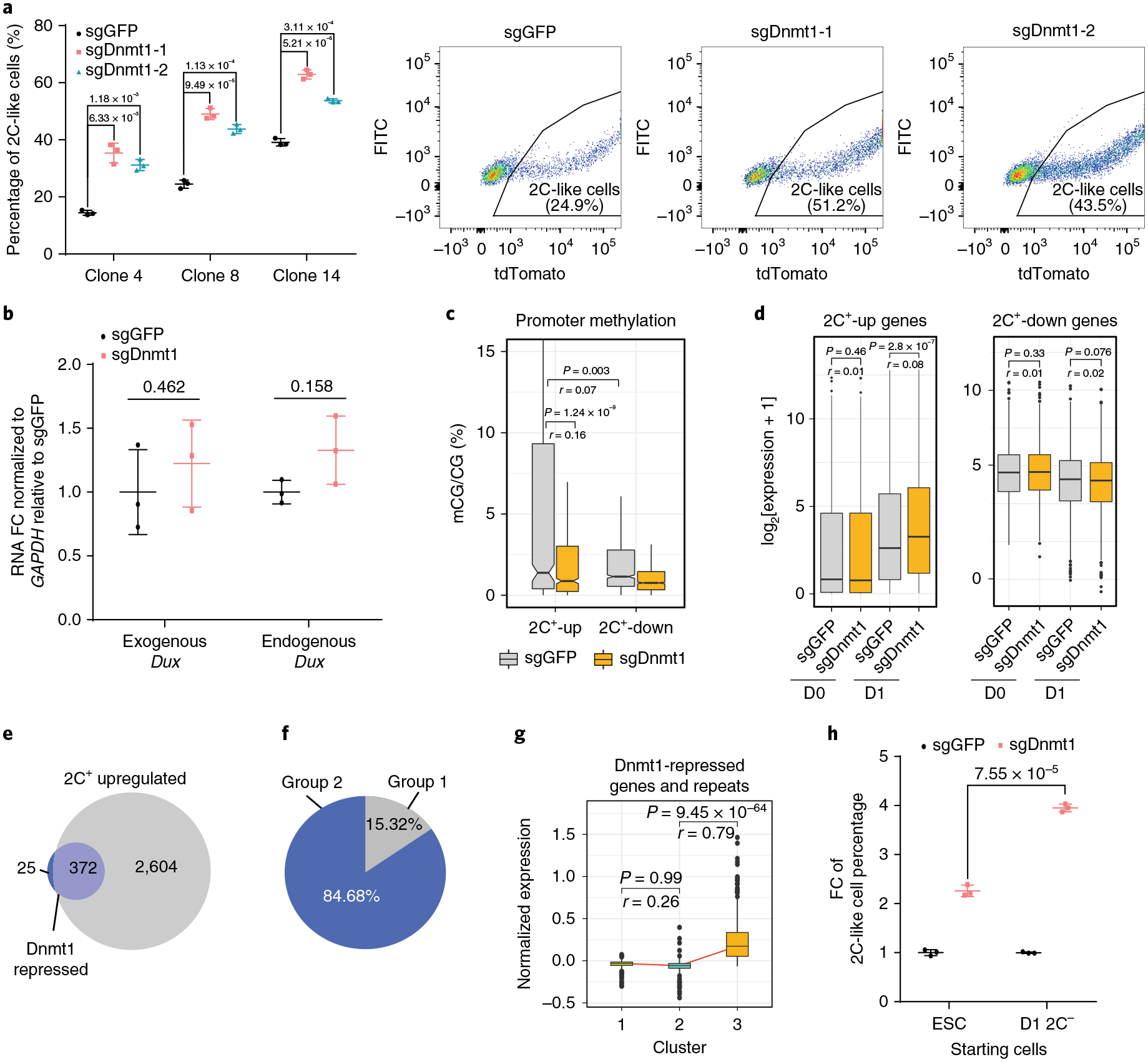

Dnmt1 impedes activation of 2C+-upregulated genes during the intermediate to 2C-like cell transition.

Dnmt1 is responsible for maintaining the DNA methylation pattern during cell division31. Interestingly, ESCs undergo global DNA demethylation when they enter the 2C-like state18,32, suggesting a potential negative role of DNA methylation in the 2C-like transition. Furthermore, Dnmt1 is identified as a top candidate impeding the 2C-like transition (Fig. 3b). These observations prompted us to investigate the role of Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in the 2C-like transition.

To this end, we designed two sgRNAs targeting Dnmt1 and confirmed their efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 6a). After Dux induction, we found that Dnmt1 deficiency significantly increased the 2C-like-cell population in three ESC clones (Fig. 5a). Notably, sgDnmt1 exhibited no effect on 2C-like-state maintenance, suggesting that Dnmt1 deficiency increases 2C-like cells by facilitating the 2C-like transition (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Dux expression is not altered in Dnmt1-deficient cells (Fig. 5b), indicating that Dnmt1 mediated the 2C-like transition independent of Dux expression. In addition, Dnmt1 deficiency also increased the spontaneous 2C-like transition (Supplementary Fig. 6c), suggesting that the effect of Dnmt1 on the 2C-like transition is independent of the Dux transgene.

Fig. 5 |. Dnmt1 impedes activation of 2C+-upregulated genes during the late stage of the ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

a, The percentage of 2C-like cells after 1 d Dux induction of the indicated manipulation in three independent ESC clones and representative FACS from clone 8. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. b, The relative expression (quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (qRT-PCR)) of endogenous and exogenous Dux normalized to Gapdh after 1 d induction. FC, fold change. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. c, Promoter (TSS± 1 kb) methylation of 2C+-upregulated (n = 751 genes) and -downregulated (n = 1,170 genes) genes in sgDnmt1- and sgGFP-treated cells measured by reduced-representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS). d, The expression level of 2C+-upregulated (n = 2,285 genes) and 2C+-downregulated (n = 2,724 genes) genes. e, A Venn diagram showing overlaps of Dnmt1-repressed genes/repeats and 2C+-upregulated genes/repeats (372 out of 397, 93.7%). Dnmt1-repressed genes/repeats (283 genes and 114 repeats) are defined as elements that are further activated in sgDnmt1 cells compared to sgGFP cells on Dux induction (FC > 2 and P value < 0.001). f, A pie chart showing the relative percentage of group 1 and group 2 genes in Dnmt1-repressed genes/repeats. g, A box plot showing the log2 expression in each cell cluster of Dnmt1-repressed genes/repeats detected in single-cell data (n = 227 genes/repeats). h, The fold change (FC) of the 2C-like cell population after 1 d Dux induction in sgDnmt1 relative to the sgGFP control. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. In a,b,h, the P values (indicated as numbers in the graphs) were calculated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, two-sample unequal variance. The experiments were repeated independently twice with similar results. In c,d,g, the black central line is the median, the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles, the whiskers indicate the 1.5 interquartile range and the dots represent outliers. P values were calculated by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests and effect sizes (shown as r) were calculated as , where Z is the Z value of the Mann–Whitney U-test and N is the number of samples. c-g were based on two independent replicates of RNA-seq experiments. Statistical source data can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

The analysis of publicly available DNA methylomes of ESCs and 2C-like cells18 indicated that the promoters of 2C+-upregulated genes undergo more significant demethylation compared to that of 2C+-downregulated genes in 2C-like cells (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Given that Dnmt1 is critical for maintaining DNA methylation31, we hypothesized that Dnmt1-mediated DNA methylation serves as a repressor to prevent gene upregulation during the transition. Indeed, the promoter methylation of 2C+-upregulated genes is more significant than that of 2C+-downregulated genes in mESCs (Fig. 5c). Importantly, Dnmt1 deficiency significantly decreased the promoter methylation of 2C+-upregulated genes (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 6), implying that Dnmt1 maintains the promoter methylation of 2C+-upregulated genes in mESCs.

If Dnmt1 functions as a barrier for gene activation during the 2C-like transition, the induction of these genes should be more evident in Dnmt1-deficient cells. Indeed, 2C+-upregulated elements were further activated in Dnmt1-deficient cells (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 7), while 2C+-downregulated genes showed no significant increase in Dnmt1-deficient cells (Fig. 5d). Taken together, these results indicate that Dnmt1 preferentially prevents activation of 2C+-upregulated genes during the transition.

Activation of 2C-embryo-specific elements occurs mainly during the intermediate to 2C-like state transition (Fig. 2h). Since Dnmt1 impedes the activation of 2C+-upregulated genes during the transition, it is likely that Dnmt1 prevents the intermediate to 2C-like cell transition.

To test this possibility, we focused on the elements that are further upregulated in Dnmt1-deficient cells after Dux activation (FC > 2 and P value < 0.001) (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Table 7). The majority of these elements belong to 2C+-upregulated genes (Fig. 5e). Interestingly, these Dnmt1-repressed 2C+-upregulated elements mostly belong to group 2 (Fig. 5f). scRNA-seq revealed that activation of these genes/repeats mainly takes place during the intermediate to 2C-like cell transition (Fig. 5g), suggesting that Dnmt1 majorly impedes the transition at this stage. Furthermore, in contrast to Myc, depletion of Dnmt1 caused a more evident increase in the 2C-like population in D1 2C− cells than in ESCs (Fig. 5h). Collectively, these data support that Dnmt1 serves as a barrier mainly during the intermediate to 2C-like cell transition.

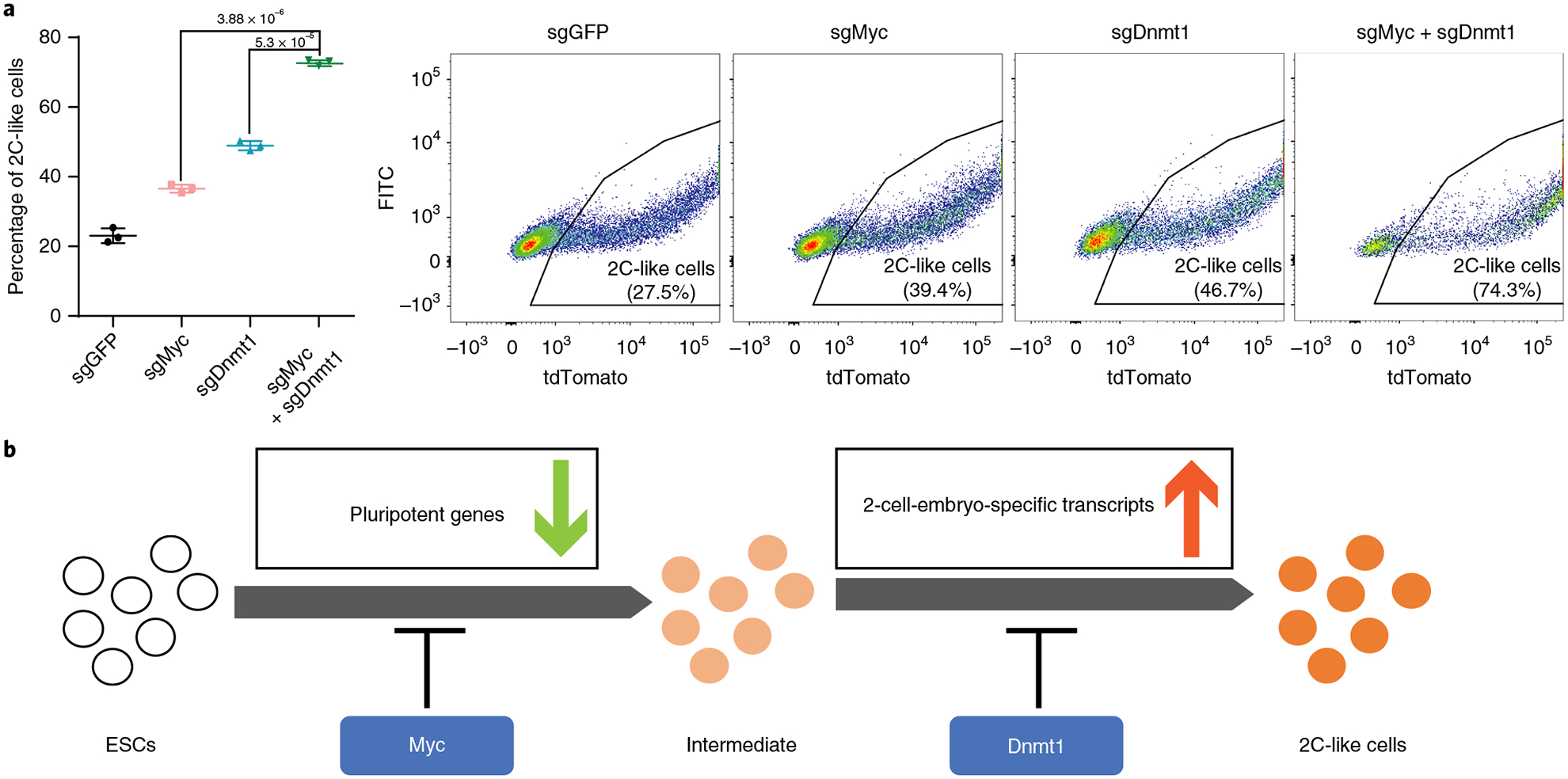

Since Myc and Dnmt1 prevent the 2C-like transition at different stages, we anticipate that removal of both barriers should have an additive effect. Indeed, ESCs infected with Dnmt1 and Myc sgRNAs exhibited a further increase in the 2C-like transition on Dux induction compared to that of single sgRNA infection (Fig. 6a), supporting the finding that Myc and Dnmt1 function independently during the transition.

Fig. 6 |. Dnmt1 and Myc may impede the two-step transcriptional reprogramming of the ESC to 2C-like cell transition.

a, The percentage of 2C-like cell population after 1 d Dux induction alone or combined sgMyc and sgDnmt1 relative to the sgGFP control. Shown are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent cell cultures. Representative FACS results are shown. P values (indicated as numbers in the graphs) were calculated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed, two-sample unequal variance. The experiment was repeated independently twice with similar results. b, A model showing that Dnmt1 and Myc impede the transcriptional reprogramming of the 2C-like transition at different stages. Statistical source data can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

Discussion

The spontaneous 2C-like transition is induced by Dux15–17. It is believed that Dppa2/4 activate Dux in mESCs to initiate the 2C-like transition33,34. However, the mechanisms underlying the transcriptomic dynamics during the transition after Dux activation remained elusive. To fill in this knowledge gap, we performed scRNA-seq and CRISPR–Cas9-mediated screening to dissect the transcriptional dynamics and identify relevant regulators.

Unlike previous studies13,18, our study exploited Dux to drive the transition, and revealed two stages of reprogramming during the transition: an early stage characterized by the downregulation of pluripotent genes and a late stage characterized by the activation of 2-cell-embryo-specific elements (Fig. 6b). This dynamic process indicates that activation of 2-cell-embryo-specific genes/repeats may require the cells to exit the pluripotent state first. Notably, prolonged Dux induction did not induce a complete 2C-like transition as Dux induction initiates an unsynchronized 2C-like transition and cannot maintain the 2C-like state (Supplementary Fig. 6e).

A recent study of the 2C-like transition identified a Zscan4+ intermediate state13 by analysing the expression of 93 genes. The expression dynamics of these genes are similar to that of our scRNA-seq (Supplementary Table 3). Importantly, on the basis of unbiased scRNA-seq of the Dux-induced 2C-like transition, we were able to dissect the transcriptional dynamics of the 2C-like transition and identify an unappreciated intermediate state. Since the intermediate-state cells are rare (<5%, Fig. 2f) and cannot be isolated by analysing a limited number of mESCs harbouring MERVL or Zscan4 reporter, they were not identified in the previous studies (Supplementary Fig. 6f,g).

Previously reported factors that inhibit the 2C-like transition, such as CAF1, mainly affect the transition through repressing Dux4,10,17,35,36. However, factors that mediate the transition after Dux activation are largely unknown. To fill in this knowledge gap, we performed a CRISPR–Cas9 screen under Dux-induction conditions and revealed functionally diverse candidates, including Myc and Dnmt1. Importantly, we demonstrated that Myc impedes the early stage of the 2C-like transition through its transcriptional amplification on 2C+-downregulated genes27,29,30, while Dnmt1 impedes the activation of 2C+-upregulated genes (Fig. 6b). Notably, Myc and Dnmt1 exhibit unimodal expression in mESCs (Supplementary Fig. 6h,i). Thus, the incomplete 2C-like transition following Dux expression is unlikely to be due to the expression heterogeneity of Myc and Dnmt1 in mESCs.

In conclusion, our study not only reveals a two-stage transcriptional reprogramming process during the 2C-like transition, but also suggests that the regulatory network governing the transition may involve several distinct machineries that can be explored in the future.

Methods

ESC culture and establishment of cell lines with inducible Dux expression.

The ES-E14 cells were cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated plates with standard LIF/serum medium containing 15% FBS (Sigma, cat. no. F6178), 1,000 U ml−1 mouse LIF (Millipore, cat. no. ESG1107), 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (Gibco, cat. no. 11140), 0.055 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco, cat. no. 21985023), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco, cat. no. 35050), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco, cat. no. 11360) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U ml−1) (Gibco, cat. no. 15140). For culture of ESC lines, the medium was changed daily, and cells were routinely passaged every other day. The transcriptome of our mESCs is highly similar to that of a published ES-E14 dataset (Pearson correlation, r = 0.92)38. The E14 cell line was kindly provided by the laboratory of B. Koller. The MERV-L-LTR-tdTomato reporter constructs were kindly provided by the laboratory of S. L. Pfaff4 and were linearized and transfected into E14 cells by electroporation. Colonies containing tdTomato-positive cells were then picked and expanded. The Dux sequence was codon-optimized, synthesized by IDT and inserted into pCW57-MCS1-P2A-MCS2 (Neo) (Addgene 89180). ESCs with the 2C::tdTomato reporter were infected with a plasmid expressing Dux and selected with neomycin for one week. Single clones were picked for further experiments. To ensure that Dux-induced 2C-like cells resemble the spontaneous 2C-like cells and to avoid potential side effects of Dux overexpression, we choose clone 8 for bulk RNA-seq as the Dux induction level in this clone is comparable to the Dux level in spontaneous 2C-like cells (~100-fold, Supplementary Fig. 1c)16. The sequence of codon-optimized Dux was included in Supplementary Table 8.

FACS.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed using the BD FACSCanto II, and cell sorting was performed on the BD FACSAria II cell sorter. Data and images were analysed and generated using Flowjo (V10) software. The gating strategy was shown in FACS figures. The following antibodies were used in FACS: Myc (1:50, Proteintech, 10828–1-AP, lot number 00060703), Dnmt1 (1:50, Cell Signaling, 5032T, D63A6, lot number 1), Rex1 (1:200, Novus, NBP2–37357, 5E11A6, lot number 130125), donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:250, Invitrogen, A-21206, lot number 1275888) and donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:250, Invitrogen, A-21202, lot number 1259373).

RNA isolation, qPCR and bulk RNA-seq.

Cellular RNA was collected using the Qiagen Allprep RNA/DNA mini kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 80204). Complementary DNA was generated using the SuperScrip III First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermofisher, cat. no. 18080051) and qRT-PCR was performed using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermofisher, cat. no. 4385612). Relative quantification was performed using the comparative CT method with normalization to GAPDH. The bulk RNA-seq library was prepared using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, cat. no. E7420S).

CRISPR–Cas9 knockdown and genome-wide CRISPR screening.

The gene knockdown by CRISPR–Cas9 was performed as described before39. The sgRNA sequences were included in Supplementary Table 8.

The mouse CRISPR–Cas9 library based on the lentiCRISPRv2 backbone was a gift from D. Root and J. Doench (Addgene no. 73633), containing 78,637 gRNAs targeting 19,674 genes. The plasmid DNA library was amplified according to recommended protocol (http://www.addgene.org/pooled-library/broadgpp-mouse-knockout-brie/). Lentivirus was produced using the psPAX2-PMD2.G system in 293T cells and titred. To construct the ESC library, a total of ~40 million ESCs with the MERVL reporter and Dux transgene were transduced with lentivirus for 48 h in the presence of 4 μg ml−1 Polybrene to reach an infection efficiency of ~15%. After 2 d infection, cells were cultured in medium containing 1 μg ml−1 puromycin for another 8 d to select for infected cells. For the screen, ~30 million puromycin-selected cells were treated with 2 μg ml−1 doxycycline for 1 d to induce Dux expression and the 2C-like transition in the culture. Around 1 million 2C-positive cells and 10 million 2C-negative cells were then collected through FACS based on tdTomato reporter expression. Genomic DNA of 2C-positive and -negative cells was extracted through the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (cat. no. 69504). Guide RNA sequences were then amplified using P5 primer (5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACAC TCTTT CCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACC G-3′) and P7 primer (5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATNNNNNNNNGT GACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCAATTCCCACTCCTTTCA AGACCT-3′; NNNNNNNN refers to a 8-base-pair (bp) index) through KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (cat. no. KK2602). For each sample, four parallel PCR reactions were set up, and mixed products from four reactions were then purified through AMPure XP reagents (1.0×) and sequenced by an Illumina HiSeq 2500 Sequencer. The designed CRISPR–Cas9 library expressed 79,632 gRNAs targeting 19,674 genes. Two screen replicates (independent Dux induction and FACS isolation) were performed. The sequencing results were analysed by the MAGeCK package24, which took into consideration the magnitude of enrichment/depletion and the consistency of multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene, to rank positive/negative regulators.

Drop-seq.

Drop-seq was performed as described previously40. ESCs with the MERVL reporter and synDux were induced with doxycycline for the designated time and collected for Drop-seq.

Genomic annotation file preparation.

The gtf file corresponding to the mm10 Ensemble GRCm38.85 transcriptome was downloaded from the Ensemble database. The sequences of the synthetic-Dux and TdTomato were added to the mm10 genomic annotation file. The gtf files were converted to refFlat format using the UCSC gtfToGenePred tool (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/admin/exe/linux.x86_64/gtfToGenePred), and then the refFlat file was converted to a format compatible with the Drop-seq tool (v1.13) using a custom script.

Repeat pseudo-genome preparation.

As repeat elements tend to have multiple highly similar copies along the genome, it is relatively complex to accurately align them and estimate their expression. Hence, we created a repeat pseudo-genome. We used a slightly modified version of the RepEnrich (v0.l)41 software. Briefly, for each repetitive element subfamily, a pseudo-chromosome was created by concatenating all genomic instances of that subfamily along with their flanking genomics 15 bp sequences and a 200 bp spacer sequence (a sequence of Ns). The pseudo-genome was then indexed using STAR (v.2.5.2b)42 and the corresponding gtf and refFlat files were created using custom scripts and by considering each pseudo-chromosome as one gene.

Sequencing alignment for coding genes.

Raw reads were first trimmed using Trimmomatic (v.0.36). Illumina sequence adaptors were removed, the leading and tailing low-quality base pairs (fewer than 3) were trimmed, and a 4-bp sliding window was used to scan the reads and trim when the window mean quality dropped below 15. Only reads having at least 50-bp were kept. The resulting reads were mapped to the mm10 genome using STAR42 (v.2.5.2b) with the following parameters: -outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate – outSAMunmapped Within –outFilterType BySJout -outSAMattributes NH HI AS NM MD -outFilterMultimapNmax 20 -outFilterMismatchNmax 999 -quantMode TranscriptomeSAM GeneCounts. The generated gene expression count files generated by STAR were then used for estimating gene expression.

Sequencing alignment for repeats.

Multi-mapped reads and reads mapping to intronic or intergenic regions were extracted and then mapped to the repeat pseudo-genome. First, the TagReadWithGeneExon command of the dropseq tools (v1.13)43 was used to tag the reads into utr, coding, intergenic and intronic reads using the bam tag ‘XF’. Multi-mapped reads, intergenic and intronic reads were extracted and mapped to the repeat pseudo-genome using STAR. The STAR read counts were used as an estimate of repeat expression.

Bulk RNA-seq normalization.

For each sample, the gene and repeat expression matrices were merged together and then the ‘Trimmed Mean of M values’ normalization (TMM) method44 from the R/Bioconductor package edgeR package (v3.24.0) was used to calculate the normalized expression37,45.

Differential gene expression analysis of bulk RNA-seq data.

The R/Bioconductor edgeR package (v3.24.0)37,45 was used to detect the differentially expressed genes between the different samples using the generalized linear model-based method. Genes showing more than twofold expression change and an FDR < 0.0001 were considered as differentially expressed.

Functional enrichment analysis.

The functional enrichment analysis was performed by using IPA QIAGEN Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis/(v01–13)46. The associated GO and pathway enrichment plots were generated using the ggplot2 package (v3.1.0).

Drop-seq expression matrix generation and pre-processing.

For gene expression quantification in Drop-seq, the raw Drop-seq data were processed using dropseq tools (v1.13)43. Reads were mapped against the mm10 genome (GRCm38) and the Ensemble GRCm38.85 transcriptome was used for gene annotation. Initially, the gene expression of the top 2,000 abundant cell barcodes was generated (DigitalExpression command of dropseq tools with the option NUM_CORE_BARCODES=2000). To estimate the repeat expression, the bam tag ‘XF’ added by the dropseq tools’ TagReadWithGeneExon was used to extract non-mapped reads and reads mapping to intronic and intergenic regions. The extracted reads were mapped to the repeat pseudo-genome using dropseq tools. The expression matrix of the top 2,000 enriched cell barcodes was generated. For each time point, the expression matrix of the cell barcodes detected in both the reads and genes was generated. The Seurat R package (v2.3.0)47 was then used to load and pool all of the dataset together. We filtered out cells with <800 detected transcripts and cells in which the mitochondrial transcriptome occupies >10% of the total transcripts. Genes expressed in fewer than three cells were excluded.

Drop-seq normalization.

Due to the sparsity of the Drop-seq data and the contribution of Dux-induced genes to most of the reads, a normal read depth normalization will lead to the shrinkage of the expression of many genes. Hence, we used the deconvolution-based normalization method available in the R/Bioconductor scran package (v1.10.1)48. Briefly, cells are ordered by their library size and segregated into pools using a sliding window ranging from 20 to 100. The sum of expression in each pool is then normalized to the average expression of all cells. The pool-based size factors are estimated and deconvolved to their cell-based counterparts.

Drop-seq data clustering and marker gene detection.

The Seurat R package47 was used for clustering analysis. Briefly, 309 variable genes showing a dispersion (variance/mean) of at least two standard deviations from the expected dispersion were selected (FindVariableGenes function of the Seurat R package). The top 30 principal components (PCs) were then calculated using the variable genes. The significant PCs were selected using the Jackstraw method available in the Seurat R package and their coordinates were used for clustering (FindClusters function in the Seurat package with resolution = 0.4). The marker genes were then detected by comparing each cluster to all of the others using a likelihood ratio49 using the FindAllMarkers function of the Seurat R package. Genes showing at least 1.5-fold enrichment and expressed in at least 60% of the cells in the target cluster and <20% of the other cells were selected as marker genes. The low-dimensional projection representation of the data was performed using uniform manifold approximation and projection50 implemented in the uwot R package (https://github.com/jlmelville/uwot) using the 11 most significant PCs as input.

Pseudo-time construction.

The Monocle package (v2.10.0)51 was used to generate the pseudo-time. Briefly, the normalized expression data were used to create a Monocle object with the ‘expressionFamily’ parameters set to ‘gaussianff’. Next, variable genes detected by Seurat were used to define the cells’ progress by calling the function ‘setOrderingFilter’. Then, the data dimensionality was reduced using Monocle’s DDRTree method using the function ‘reduceDimension’. Finally, the pseudo-time was constructed using the ‘orderCells’ method.

Clustering of Drop-seq clusters and RNA-seq samples.

The 309 variable genes/repeats identified from Drop-seq were used to compare the mean expression profile of the clusters identified in Drop-seq to the expression profile of bulk RNA-seq samples. As the expression profiles were generated using two different technologies, the technical batch effect had to be removed. Therefore, we used the ‘ComBat’ function from the R/Bioconductor sva package (3.30.1)52 to regress-out the technical effect. The first two PCs of the corrected expression were calculated using the ‘prcomp’ R function and then a complete-linkage hierarchical clustering was performed.

RRBS and data analysis.

DNA (1 ng) with a 0.5% non-methylated λ DNA spike-in was digested by MspI for 3.5 h. DNA was then end-repaired, dA-tailed and ligated with methylated adaptors. Bisulfite conversion was carried out using an EpiTect fast bisulfite conversion kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bisulfite-converted DNA was then amplified with five PCR cycles to obtain the final library. The RRBS libraries were subjected to pair-end (2 × 110 bp) sequencing on a HiSeq 2500 (Illumina). Raw reads were first trimmed using TrimGalor (v0.4.5) with parameters ‘--three_prime_clip_R1 2 --length 35’ then mapped the mm10 genome using Bismark (v0.20.0) and bowtie2 (v2.3.4.3). Reads mapping to the positive and negative strand were extracted separately using samtools then the methylation levels were estimated using bismark_methylation_extractor. CpG sites overlapping with known single nucleotide polymorphisms were removed and sites with at least 5× coverage were used for the downstream analysis. Promoters were defined as TSS ± 1 kb and only promoters harbouring at least 3 CpG sites were considered.

Western blotting.

Protein was purified using M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific, cat. no. 78501) with protease inhibitor (Roche, cat. no. 4693159001). Western blotting was carried out with 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gel (Invitrogen, NP0322BOX) with the following antibodies: Myc (1:1,000, Proteintech, 10828–1-AP, lot number: 00060703), Dnmt1 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 5032T, D63A6, lot number 1), Gapdh (1:10,000, Ambion, AM4300, 6C5, lot number 00562237), goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody, HRP (1:10,000, Invitrogen, 31430, lot number QD216575) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody, HRP (1:10,000, Invitrogen, 31460, lot number RB230194).

ESC and spontaneous 2C-like methylation data analysis.

We used the publicly available ESC and 2C-like (MuERVL+, Zscan4+) PBAT methylation data available under GEO accession numbers (GSM1966777, GSM1966778, GSM1966779, GSM1966780, GSM1966781 and GSM1966782)18. We directly used the mm10 processed data deposited by the authors. Briefly, the stranded CpG methylation profile was first converted into an unstranded profile by combining the positive and negative signal, then the methylation was estimated as the number of detected Cs compared to the total coverage. Only promoters harbouring at least 3 CpG sites were considered.

Dux and Myc ChIP-seq data analysis.

Dux ChIP-seq data were downloaded from a previous publication16 under GEO accession number GSE95517. The Myc ChIP-seq dataset was from ref.28 with GEO accession number GSM1171648. Raw reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic53 and then mapped to the mm10 genome using Bowtie254 (v2.2.9). Multi-mapped and unmapped and low-quality reads were removed using samtools55 (v1.3.1) and PCR duplicates were removed using the MarkDuplicates command from Picard tools (v2.8.0).

Statistics and reproducibility.

Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test (two-tailed) or a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test for datasets with non-normal distribution, as indicated in the corresponding figure legends. For the t-test, Welch’s correction was used for unequal variance. Boxes in all box plots extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles, with a line at the median. The whiskers show the minimum and maximum values. Statistical tests were performed using Prism7 (GraphPad Software) or R. The size effects for the Mann–Whitney (U-test were calculated as , where Z is the Z value of the Mann–Whitney (U-test (obtained using the coin R package) and N is the number of samples. For the t-test, we used the unbiased Hedge’s g effect with the Hedge’s effect size correction applied . Pearson correlation was calculated using the cor function in R. All sequencing experiments presented in the manuscript were independently performed twice and the quality information is included in Supplementary Table 9. All other experiments were performed at least twice independently with similar results with each experiment involving at least three biological samples.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. L. Pfaff for providing the MERVL-tdTomato reporter, F Lu for assistance with the establishment of the reporter cell line and Z. Chen for critical reading of the manuscript. This project was supported by the NIH (R01HD092465) and HHMI. Y.Z. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Data availability

RNA-seq, Drop-seq, RRBS and CRISPR screen-related data, including the sgRNA read counts, that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession code GSE121459. Previously published sequencing data that were reanalysed here are available in the GEO under the accession codes GSE85766 (Promoter methylation in ESCs and 2C-like cells), GSE95517 (Dux ChIP-seq) and GSM1171648 (Myc ChIP-seq), and the samples GSM1966767, GSM1966768 and GSM1966769 (Zscan+ and MuERVL+ spontaneous 2C-like cell transcriptome)16,18,28. Source data for all figures have been provided as Supplementary Table 10. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All of the codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, statements of code and data availability and associated accession codes are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-019-0343-0.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/S41556-019-0343-0.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee MT, Bonneau AR & Giraldez AJ Zygotic genome activation during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 30, 581–613 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu F & Zhang Y Cell totipotency: molecular features, induction, and maintenance. Natl Sci. Rev 2, 217–225 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falco G et al. Zscan4: a novel gene expressed exclusively in late 2-cell embryos and embryonic stem cells. Dev. Biol 307, 539–550 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macfarlan TS et al. Embryonic stem cell potency fluctuates with endogenous retrovirus activity. Nature 487, 57–63 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y et al. Derivation of pluripotent stem cells with in vivo embryonic and extraembryonic potency. Cell 169, 243–257.e25 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J et al. Establishment of mouse expanded potential stem cells. Nature 550, 393–397 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao S et al. Derivation of hypermethylated pluripotent embryonic stem cells with high potency. Cell Res. 28, 22–34 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li M & Izpisua Belmonte JC Deconstructing the pluripotency gene regulatory network. Nat. Cell Biol 20, 382–392 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boskovic A et al. Higher chromatin mobility supports totipotency and precedes pluripotency in vivo. Genes Dev. 28, 1042–1047 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishiuchi T et al. Early embryonic-like cells are induced by downregulating replication-dependent chromatin assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 22, 662–671 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker CL & Pera MF Capturing totipotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 22, 25–34 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu F, Liu Y, Jiang L, Yamaguchi S & Zhang Y Role of Tet proteins in enhancer activity and telomere elongation. Genes Dev. 28, 2103–2119 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Terrones D et al. A molecular roadmap for the emergence of early-embryonic-like cells in culture. Nat. Genet 50, 106–119 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi YJ et al. Deficiency of microRNA miR-34a expands cell fate potential in pluripotent stem cells. Science 355, eaagl927 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiddon JL, Langford AT, Wong CJ, Zhong JW & Tapscott SJ Conservation and innovation in the DUX4-family gene network. Nat. Genet 49, 935–940 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrickson PG et al. Conserved roles of mouse DUX and human DUX4 in activating cleavage-stage genes and MERVL/HERVL retrotransposons. Nat. Genet 49, 925–934 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Iaco A et al. DUX-family transcription factors regulate zygotic genome activation in placental mammals. Nat. Genet 49, 941–945 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckersley-Maslin MA et al. MERVL/Zscan4 network activation results in transient genome-wide DNA demethylation of mESCs. Cell Rep. 17, 179–192 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eidahl JO et al. Mouse Dux is myotoxic and shares partial functional homology with its human paralog DUX4. Hum. Mol. Genet 25, 4577–4589 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar RM et al. Deconstructing transcriptional heterogeneity in pluripotent stem cells. Nature 516, 56–61 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolodziejczyk AA et al. Single cell RNA-sequencing of pluripotent states unlocks modular transcriptional variation. Cell Stem Cell 17, 471–485 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith A Formative pluripotency: the executive phase in a developmental continuum. Development 144, 365–373 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doench JG et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR–Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol 34, 184–191 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 15, 554 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chappell J & Dalton S Roles for MYC in the establishment and maintenance of pluripotency. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 3, a014381 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J et al. A Myc rather than core pluripotency module accounts for the shared signatures of embryonic stem and cancer cells. Cell 143, 313–324 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nie Z et al. c-Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells. Cell 151, 68–79 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krepelova A, Neri F, Maldotti M, Rapelli S & Oliviero S Myc and max genome-wide binding sites analysis links the Myc regulatory network with the polycomb and the core pluripotency networks in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 9, e88933 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Percharde M, Bulut-Karslioglu A & Ramalho-Santos M Hypertranscription in development, stem cells, and regeneration. Dev. Cell 40, 9–21 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CY et al. Transcriptional amplification in tumor cells with elevated c-Myc. Cell 151, 56–67 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones PA & Liang G Rethinking how DNA methylation patterns are maintained. Nat. Rev. Genet 10, 805–811 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dan J et al. Zscan4 inhibits maintenance DNA methylation to facilitate telomere elongation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 20, 1936–1949 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Iaco A, Coudray A, Duc J & Trono D DPPA2 and DPPA4 are necessary to establish a 2C-like state in mouse embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 20, e47382 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eckersley-Maslin M et al. Dppa2 and Dppa4 directly regulate the Dux-driven zygotic transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 33, 194–208 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell AE et al. NuRD and CAF-l-mediated silencing of the D4Z4 array is modulated by DUX4-induced MBD3L proteins. eLife 7, e31023 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Percharde M et al. A LINE1-nucleolin partnership regulates early development and ESC identity. Cell 174, 391–405.e19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ & Smyth GK edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shalem O et al. Genome-scale CRISPR–Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen R, Wu X, Jiang L & Zhang Y Single-cell RNA-seq reveals hypothalamic cell diversity. Cell Rep. 18, 3227–3241 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Criscione SW, Zhang Y, Thompson W, Sedivy JM & Neretti N Transcriptional landscape of repetitive elements in normal and cancer human cells. BMC Genomics 15, 583 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobin A et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macosko EZ et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson MD & Oshlack A A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 11, R25 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y & Smyth GK Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 4288–4297 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J Jr. & Tugendreich S Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 30, 523–530 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E & Satija R Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 411 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lun AT, Bach K & Marioni JC Pooling across cells to normalize single-cell RNA sequencing data with many zero counts. Genome Biol. 17, 75 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDavid A et al. Data exploration, quality control and testing in single-cell qPCR-based gene expression experiments. Bioinformatics 29, 461–467 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mclnnes L, Healy J, Saul N & Großberger L UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection. J. Open Source Softw 3, 861 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trapnell C et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 381–386 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, Jaffe AE & Storey JD The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 882–883 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolger AM, Lohse M & Usadel B Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M & Salzberg SL Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.