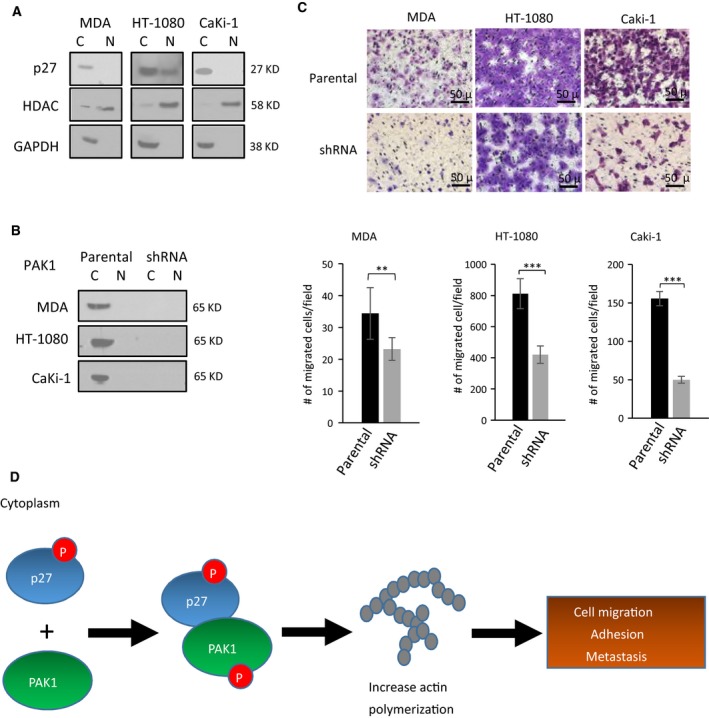

Figure 6.

Migration inhibitory effect of PAK1 silencing on non‐OS cell lines with p27 mislocalization. (A) Western blotting with subcellular fractionation of three non‐OS cancer cell lines. GAPDH and HDAC were used as nuclear and cytoplasmic protein controls, respectively (C, cytoplasmic fraction; N, nuclear fractions). (B) Western blotting of PAK1‐shRNA mutants and parental controls in the three cancer cell lines showing high efficiency of PAK1 knockdown. (C) Representative images and quantification of transwell migration assays showing migrated cells in the three PAK1‐shRNA mutants relative to their parental cells. Migrated cells were stained, counted, and averaged using imagej software in five random and independent microscopic fields (10×). Error bars represent standard deviations of the replicates, and asterisks denote statistical significance (Student's t‐test; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ns, not significantly, respectively). All experiments were replicated three times. (D) A model depicting how p27 mislocalization may lead to increased incidence of metastatic progression in the OS patients. Phosphorylated p27 in the cytoplasm interacts with PAK1, and the resulting protein–protein interaction activates PAK1 by protein phosphorylation. The PAK1 phosphorylation promotes actin polymerization and increases stress fiber formation in OS cells, leading to higher tumor cell migration and adhesion and, hence, metastasis.