Abstract

In this work, the preparation of novel calcium citrate (CaCit) nanoparticles (NPs) has been disclosed and the use of these NPs as “Trojan” carriers has been demonstrated. The concentration ratio between calcium ions and citrate ions was optimized, yielding spherical NPs with size in the range of 100–200 nm. Additionally, a fluorescent dye, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), was successfully encapsulated by the coprecipitation method. The products were characterized by thermogravimetric analysis and scanning electron microscopy. The cellular uptake was investigated by incubating the synthesized fluorescent-tagged NPs with human keratinocytes using a confocal microscope. The accumulation of the FITC in the cells suggested that the CaCit NPs can potentially be used as novel drug carriers.

Introduction

Drug delivery has recently gained increasing interest as a method for administering pharmaceutical compounds to achieve therapeutic effects in humans or animals. Nanoparticle (NP)-based drug delivery systems have considerable potential in clinic for a variety of applications because of their ability to enable improvement of drug bio-availability and retention at the target intracellular site of action by active and passive targeting by NPs.1,2 In particular, calcium carbonate NPs (Figure 1a) are one of the most commonly used calcium ionic compounds for drug carriers owing to their availability, low cost, safety, biocompatibility, and slow biodegradability.3 However, because of their high sensitivity toward acidic conditions, the drug encapsulated in the CaCO3 NPs cannot be administered orally, although this limitation was overcome to some extent using an enteric coating technique.4 In addition, because CaCO3 can adopt various crystalline polymorphs, it is generally very challenging to control the size of the CaCO3 NPs, resulting in a relatively broad size distribution,5 which may hinder further applications of such NPs. Another major drawback of CaCO3 NPs is the tendency to aggregate due to the high lattice energy of CaCO3. This limitation not only affects the shelf life of the pharmaceuticals made from CaCO3 NPs but also denies the possibility to store the NPs in a solid form because redispersion is relatively difficult.6

Figure 1.

(a) Calcium carbonate NPs; (b) citrate–apatite nanocrystals; and (c) “Trojan” CaCit NPs (this work).

To overcome these limitations, we set out to find an alternative ionic calcium salt that may lead to a novel type of NPs with superior properties for drug carriers. In this regard, we were interested in calcium citrate (CaCit) because the citrate ion itself is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in the metabolism of all aerobic organisms.7 In addition, CaCit has been proved to be biocompatible, as illustrated in the work reported by Li and co-workers in 2016;8 CaCit nanosheets were prepared and used for promoting the formation of new bone in an animal model. In this work, the CaCit nanosheets were able to control the release of calcium ions in high activity and high concentration during a short period of time, thus stimulating bone formation efficiently. In addition, citrate has been successfully incorporated into other calcium salt-based nanomaterials; for example, Gómez-Morales and co-workers demonstrated the use of calcium apatite/carbonate/citrate nanocrystals as nanocarriers for delivery of doxorubicin (Figure 1b).9 In this case, the drug was loaded onto the nanocrystal via an adsorption process. Similarly, Iafisco10 and co-workers also reported the growth mechanism of apatite nanocrystals which are assisted by citrate. The excess amount of citrate ion played an important role in stabilizing amorphous calcium phosphate at the early stage and controlling the shape of the nanocrystals by the nonclassical oriented aggregation mechanism.

Despite these promising properties, the preparation of the NP drug carrier based purely on CaCit is very rare. The CaCit NPs have been successfully synthesized by Chang and co-workers in 2009 using a pulsed airflow pulverizer.11 Comparing to the micro CaCit, micro CaCO3, and nano CaCO3, the CaCit NPs showed superior enhancement of the serum calcium concentration and the whole-body bone mineral density when administered to ovariectomized mice. However, because this synthesis is a top-down process, it is not suitable to be used for the encapsulation of drug molecules for drug delivery applications. In our study, CaCit NPs were produced through a bottom-up process, which allow for drug loading, and the loading capacity can be controlled during the synthesis steps. Recently, we have successfully synthesized CaCit particles encapsulated with vancomycin and incorporated into poly(methyl methacrylate) for making bone cement with prolonged drug release character.12 However, the precipitation technique used in this work led to the formation of CaCit particles with relatively large sizes (almost 1 μm) and a high degree of size distribution. Herein, a simple method for the preparation of CaCit NPs have been unveiled and, for the first time, successfully used as “Trojan” carriers (Figure 1c). The application of these NPs as drug carriers was investigated by encapsulating fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Accordingly, FITC can be used to functionalize the NPs by simple isothermal adsorption without the addition of toxic organic molecules.13 The drug delivery could be confirmed by the fluorescence image using confocal spectroscopy.

Results and Discussion

First, we attempted to prepare the CaCit NPs using the coprecipitation method between calcium and citrate ions (Figure 2a). The effect of the concentration ratio between the two ions on the morphologies of the resulting CaCit particles was first investigated. Figure 3 illustrates the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of CaCit prepared at four different ratios of the two ions, with the concentration of the citrate ion fixed at 0.100 M. At the reaction equivalent ratio (1.5:1 Ca2+/C6H5O73–), CaCit appeared as needle-like crystals (Figure 3c), which is the most thermodynamically stable8 form of CaCit. Increasing the ratio to 1.6:1 also led to the formation of needle-like crystals (Figure 3d). Strikingly, when the ratio was decreased to 1.3:1, the resulting CaCit formed semispherical NPs with the size in the range of 100–250 nm (Figure 3b). This result is in agreement with the previous study that reported the use of the citrate ion as a stabilizer in the formation of NPs;9,10 therefore, the remaining citrate ions in our conditions could potentially act as stabilizers too. Moreover, excess of citrate ions absorbed on the surface of NPs may act as stabilizers preventing the NPs from aggregation via the electrostatic repulsion mechanism.14 However, when the ratio of calcium ions was further decreased to 1.0:1, only the small needle-like crystals of CaCit were observed (Figure 3a).

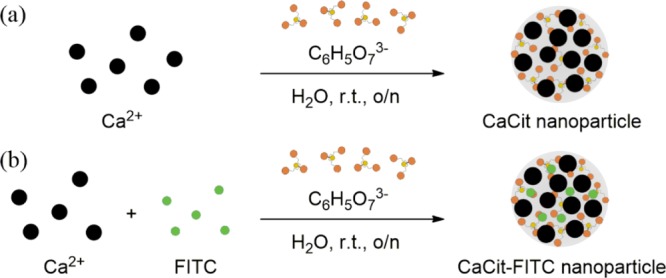

Figure 2.

(a) Preparation of the CaCit NPs using the coprecipitation method; (b) incorporation of FITC into the CaCit NPs.

Figure 3.

SEM images of CaCit (final concentration of the citrate ions = 0.100 M) at different calcium/citrate ions ratios of (a) 1.0:1, (b) 1.3:1, (c) 1.5:1, and (d) 1.6:1.

Next, the preparation of the CaCit NPs was further optimized by varying the concentrations of the ions with the ratio of Ca2+/C6H5O73– fixed at 1.3:1, as it was the only ratio that led to the formation of the desired shape of the CaCit NPs. The SEM images of the CaCit prepared at four different concentrations (Figure 4) revealed that at the highest concentration (0.200 M), a certain degree of aggregation was observed (Figure 4a). In contrast, at 0.100 M, the shape of CaCit NPs became spherical with the size range of 100–200 nm (Figure 4b). However, when lowering the concentration of citrate ions further to 0.050 M (Figure 4c) or 0.020 M (Figure 4d), CaCit occurred as sheets with an approximate size of 100–2000 nm, which are even larger than the NPs formed at 0.100 M. This observation indicated that the low concentration of the ions induced CaCit to form a thermodynamically stable shape, possibly because the high water volume encouraged the formation of tetrahydrate [Ca3(C6H5O7)2(H2O)2]·2H2O with a sheet-like shape.8

Figure 4.

SEM images of CaCit (Ca2+/C6H5O73– = 1.3:1) with different final concentrations of citrate ions: (a) 0.200 M, (b) 0.100 M, (c) 0.050 M, and (d) 0.020 M.

Figure 5 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of CaCit NPs. The results showed that the XRD pattern of the sample is corresponding to both CaCit hydrate (Figure 5b) and tri-calcium di-citrate tetrahydrate (Figure 5c). This indicated that our CaCit NPs exhibited high crystallinity. In addition, the X-ray pattern shows several faces of the CaCit crystals which may exhibit anisotropic binding with guest molecules and ions. Previous study on the CaCit nanosheet reported ethanol molecules absorbed on the 200 face, preventing the crystal from growing on this plane.8 Moreover, Iafisco and co-workers also reported that citrate plays a key dual role in apatite crystallization. The excess amount of citrate prevented the apatite from growing on a particular facade and hence controlling the size of the particles.10 Congruently, by adjusting the ratio of Ca2+ and citrate in this work, the morphology of the NPs may also be controlled by the same mechanism. The excess citrate ions could preferably absorb onto the 012 face as noticed in the relatively low intensity of this position in the X-ray pattern (Figure 5a) compared with other 2-θ positions. These citrates may prevent the crystal growth velocity of this face, altering the morphology of the CaCit crystal to be spherical rather than their natural needle-like shape. This also prevents the aggregation process of the nanocrystal from the Ostwald ripening and oriented attachment mechanism.15,16

Figure 5.

XRD pattern of CaCit: (a) CaCit nanocrystal, (b) CaCit hydrate (JCPDF no. 00-028-2003), and (c) tri-calcium di-citrate tetra-hydrate (ICSD no. 01-084-5956).

With the CaCit NPs in hand, we then investigated the potential application of these materials as drug carriers by incorporating FITC as a fluorescent probe17 into the CaCit NPs. This could be achieved by premixing calcium ions with the anionic FITC generated under basic conditions. Next, the mixture was then mixed with the citrate ion at the previously described optimum conditions, leading to the formation of CaCit-based FITC NPs (CaCit-FITC), as illustrated in Figure 2b. Using this coprecipitation method, we surmised that the FITC is chemisorbed evenly throughout the CaCit NPs, hence allowing the prolonged release of the embedded molecules. However, the exact structure needs further investigation to confirm this hypothesis. Nevertheless, the SEM images of the CaCit-FITC prepared with this method revealed that the morphology and size of the NPs were very similar to those of the abovementioned CaCit NPs (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

SEM images of CaCit-FITC (a) ×15,000 and (b) ×30,000.

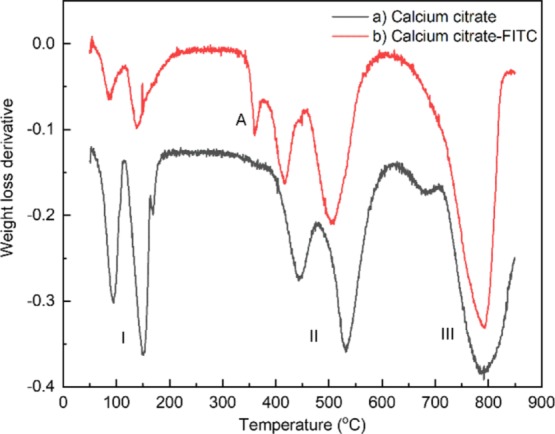

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed in order to investigate the thermal behavior of both CaCit and CaCit-FITC NPs (Figure 7). The derivative thermogravimetric curve is also shown in Figure 8. For the CaCit NPs (Figures 7a and 8a), the analysis revealed three main regions of weight loss. The first region (I), consisting of two steps, could be corresponded to the loss of water molecules. The first step between 80 and 120 °C was due to the removal of surface-adsorbed water molecules and a part of the crystal water molecules,8,18 and the second step at 120–180 °C could be assigned to the subsequent removal of two other water molecules of Ca3(C6H5O7)2·2H2O, as shown in the following equations.

Figure 7.

TGA of (a) CaCit NPs and (b) CaCit-FITC NPs.

Figure 8.

Derivative thermogravimetric curve of (a) CaCit and (b) embedded FITC CaCit.

The second region (II),8 which contributed to 24.20% of the weight loss, appears between 398 and 560 °C and can be attributed to the decomposition of CaCit into calcium carbonate (CaCO3)

Finally, the mass loss in the last region (III) is due to the decomposition of calcium carbonate into calcium oxide (CaO).

In addition to the three regions, TGA of CaCit-FITC (Figures 7b and 8b) revealed an extra peak (A) at temperatures between 345 and 395 °C, contributing to 3.50% of the total weight loss. This peak can be assigned to the decomposition of the FITC,19 thus confirming that the FITC is embedded in the CaCit NPs.

The cytotoxicity of CaCit NPs was monitored by evaluating the effects on cell viability. We found that CaCit NPs showed no cytotoxic effects with no statistically significant difference compared to the untreated control (Figure 9a). On the other hand, hydrogen peroxide, which was used as the positive control, showed significant reduction in cell viability. Moreover, there were no morphological alterations in the cell morphology in the presence of CaCit NPs at 24 h (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

Effect of CaCit NPs on HaCaT cell viability. HaCaT cells were treated with various concentrations of CaCit NPs for 24 h. (a) Cell viability was measured using the PrestoBlue reagent. (b) Morphological image of HaCaT cells observed under an inverted light microscope at 24 h. Values are expressed as means ± SD of the triplicate measurements.

The ability of CaCit NPs as drug carriers was further investigated by incubating the CaCit-FITC with human keratinocytes. The green fluorescent dye was used as a model drug, and confocal microscopy was used to monitor intracellular drug delivery. The amount of FITC inside the cells was detected by observing the fluorescence emission using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Figure 10). In contrast to the control experiment (using CaCit instead of CaCit–FITC, Figure 10a), green fluorescence could be observed in human keratinocytes after incubation with CaCit-FITC for 24 h (Figure 10b). The emissions were significantly intensified when the incubation time was increased to 48 h (Figure 10c), suggesting that FITC was indeed slowly released from the CaCit NPs in a well-controlled fashion. Moreover, the fluorescence only appeared in the cytosol, indicating the exceptional cellular uptaking property of the CaCit NPs. This also suggests the high stability of the CaCit NPs outside the cellular conditions.

Figure 10.

Confocal images of (a) human keratinocytes after incubating with CaCit; (b) human keratinocytes after incubating with CaCit-FITC for 24 h; and (c) human keratinocytes after incubating with CaCit-FITC for 48 h.

In conclusion, novel CaCit NPs were successfully synthesized via the coprecipitation method. We also found that the concentrations of both calcium ions and citrate ions strongly affect the morphologies of the resulting CaCit, ranging from needle crystals, spherical NPs, and sheets with random sizes. We also demonstrated the use of CaCit NPs as the “Trojan” carriers to release organic dyes into living cells. These findings strongly suggest that the CaCit NPs can potentially be used as a novel drug carrier with high cellular uptake.

Methods

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Materials

Anhydrous calcium chloride (≥98.0%), trisodium citrate dihydrate (≥99.0%), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥97.0%) were all obtained from Merck (Germany). Fluorescein 5(6)-isothiocyanate (≥90.0%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS buffer) was purchased from VWR Chemicals (Vienna, Austria).

Synthesis of CaCit NPs

CaCit NPs were prepared by coprecipitation between calcium ions and citrate ions with varied concentrations, as shown in Table S1 (see the Supporting Information). The calcium ion (0.200 M) or citrate ion (0.400 M) stock solutions were prepared by dissolving 0.2220 g of CaCl2 (2.00 mmol) in 5.00 mL of DI water or 0.5882 g of trisodium citrate (2.00 mmol) in 10.00 mL of DI water. The calcium ion solution was added into citrate solution while stirring. A milky suspension was slowly formed after rocking overnight at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged, and the remaining solid was washed with DI water five times and then dried at 80 °C, yielding a white solid as the desired product.

Subsequently, the reaction ratio of calcium ion and citrate ion at 1.3:1 was selected for further optimization. The stock solutions were prepared by dissolving 2.1153 g of CaCl2 (15.00 mmol) in 7.50 mL of DI water or 2.9410 g of trisodium citrate (10.00 mmol) in 10.00 mL of DI water. The reaction was performed by mixing 2.00 and 1.00 M stock solutions of calcium ion and citrate ion, respectively, with the concentrations according to Table S2 (see the Supporting Information). The calcium ion solution was added into citrate solution while stirring. After rocking overnight at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged, and the remaining solid was washed with DI water five times and then dried at 80 °C, yielding a white solid as the desired product.

Synthesis of CaCit-Based FITC NPs (CaCit-FITC)

In a test tube, a solution of FITC (0.0010 g) in NaOH (aq) (1.00 M, 375 μL) was added into the solution of CaCl2 (2.00 M, 2.00 mL). The mixture was vortexed vigorously, and then, trisodium citrate (1.00 M, 2.00 mL) was added while stirring over 10 min. After rocking overnight at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged, and the remaining solid was washed with DI water five times and then dried at 80 °C, yielding a white solid as the desired product.

Characterization of NPs

CaCit NPs were characterized using a scanning electron microscope operated at 15 kV (JSM-6480LV). Thermal analysis was carried out with an STA 409 PC TA system. The sample was placed in a platinum pan and heated at a constant rate of 10 K/min in a constant flow of nitrogen. XRD patterns were measured using a Rigaku, SmartLab 30 kV diffractomator equipped with a fixed monochromator and a Cu Kα radiation source which was set an accelerating voltage of 40 kV and applied current of 30 mA.

Cell Culture

Human keratinocytes (HaCaT) were cultured and maintained to confluence in a growth medium of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% antibiotic, and 1% FBS. Cultures were maintained in an incubator at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cell Viability Assay

The viability assay of CaCit NPs on HaCaT cells was determined using PrestoBlue reagent assay. The cells were cultured overnight and treated with various concentrations of CaCit NPs for 24 and 48 h, and a PrestoBlue reagent solution was then added to each well. After incubation, the fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation of 560 nm and emission of 590 nm using a microplate reader. The cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the cells untreated with CaCit NP treatments. The cell morphology was observed under an inverted microscope.

Drug Release of CaCit NPs

CaCit NP internalization was assessed using a confocal laser scanning microscope. HaCaT cells were seeded in confocal dishes and allowed to grow overnight. The cells were subsequently treated with 1% w/v FITC-CaCit NPs for 48 h. After the incubation time, the cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min. The fixed cell was washed three times with PBS and incubated with 300 nM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min. After thorough washing of the uninternalized dye, drug release form CaCit NPs was observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 800, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with 20× objective magnification. Digital image recording and analysis were performed using Zen software version 2.1.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Ratchadapiseksompot Fund (GCE 62018 23004-1) from Chulalongkorn University (CU) and the Development and Promotion of Science and Technology Talents Project (DPST).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00032.

Optimization conditions for the preparation of CaCit nanoparticles by varying the ratio and concentration (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Clemons T. D.; Singh R.; Sorolla A.; Chaudhari N.; Hubbard A.; Iyer K. S. Distinction Between Active and Passive Targeting of Nanoparticles Dictate Their Overall Therapeutic Efficacy. Langmuir 2018, 34, 15343–15349. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b02946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi S. A. A.; Saleh A. M. Applications of nanoparticle systems in drug delivery technology. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 64–70. 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleki Dizaj S.; Barzegar-Jalali M.; Zarrintan M. H.; Adibkia K.; Lotfipour F. Calcium carbonate nanoparticles as cancer drug delivery system. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2015, 12, 1649–1660. 10.1517/17425247.2015.1049530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Render D.; Samuel T.; King H.; Vig M.; Jeelani S.; Babu R. J.; Rangari V. Biomaterial-Derived Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Enteric Drug Delivery. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 3170248. 10.1155/2016/3170248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-A.; Kim M.-K.; Kim H.-M.; Lee J. K.; Jeong J.; Kim Y.-R.; Oh J.-M.; Choi S.-J. The fate of calcium carbonate nanoparticles administered by oral route: absorption and their interaction with biological matrices. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2273–2293. 10.2147/IJN.S79403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Mann S. Emergent Nanostructures: Water-Induced Mesoscale Transformation of Surfactant-Stabilized Amorphous Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles in Reverse Microemulsions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2002, 12, 773. 10.1002/adfm.200290006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M. Citric acid cycle and role of its intermediates in metabolism. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 68, 475–478. 10.1007/s12013-013-9750-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Liu Y.; Gao Y.; Zhong L.; Zou Q.; Lai X. Preparation and properties of calcium citrate nanosheets for bone graft substitute. Bioengineered 2016, 7, 376–381. 10.1080/21655979.2016.1226656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Casado F. J.; Iafisco M.; Delgado-López J. M.; Martínez-Benito C.; Ruiz-Pérez C.; Colangelo D.; Oltolina F.; Prat M.; Gómez-Morales J. Bioinspired Citrate–Apatite Nanocrystals Doped with Divalent Transition Metal Ions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 145–153. 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b01045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iafisco M.; Ramírez-Rodríguez G. B.; Sakhno Y.; Tampieri A.; Martra G.; Gómez-Morales J.; Delgado-López J. M. The growth mechanism of apatite nanocrystals assisted by citrate: relevance to bone biomineralization. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 507–511. 10.1039/c4ce01415d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.; Chen J. C.; Hsu C. W.; Chang W. H. Effects of nano calcium carbonate and nano calcium citrate on toxicity in ICR mice and on bone mineral density in an ovariectomized mice model. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 375102. 10.1088/0957-4484/20/37/375102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oungeun P.; Rojanathanes R.; Pinsornsak P.; Wanichwecharungruang S. Sustaining Antibiotic Release from a Poly(methyl methacrylate) Bone-Spacer. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 14860–14867. 10.1021/acsomega.9b01472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltolina F.; Gregoletto L.; Colangelo D.; Gómez-Morales J.; Delgado-López J. M.; Prat M. Monoclonal Antibody-Targeted Fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate-Labeled Biomimetic Nanoapatites: A Promising Fluorescent Probe for Imaging Applications. Langmuir 2015, 31, 1766–1775. 10.1021/la503747s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Wang D. Controlling the growth of charged-nanoparticle chains through interparticle electrostatic repulsion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47, 3984–3987. 10.1002/anie.200705537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. J. H.; Ribeiro C.; Longo E.; Leite E. R. Oriented Attachment: An Effective Mechanism in the Formation of Anisotropic Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 20842–20846. 10.1021/jp0532115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Hu X.. Hollow Micro- and Nanomaterials: Synthesis and Applications. In Advanced Nanomaterials for Pollutant Sensing and Environmental Catalysis, 1st ed.; Zhao Q., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, 2020; pp 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs J. L.; Seiwald R. J.; Burckhalter J. H.; Downs C. M.; Metcalf T. G. Isothiocyanate compounds as fluorescent labeling agents for immune serum. Am. J. Pathol. 1958, 34, 1081–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdtweck E.; Kornprobst T.; Sieber R.; Straver L.; Plank J. Crystal Structure, Synthesis, and Properties of tri-Calcium di-Citrate tetra-Hydrate [Ca3(C6H5O7)2(H2O)2]·2H2O. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2011, 637, 655–659. 10.1002/zaac.201100088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Qiao L.; Zhang Q.; Yan H.; Liu K. Enhanced cell uptake of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles through direct chemisorption of FITC-Tat-PEG(6)(0)(0)-b-poly(glycerol monoacrylate). Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 430, 372–380. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.