Abstract

Super resolution microscopy (SRM) has overcome the historic spatial resolution limit of light microscopy, enabling fluorescence visualization of cellular structures and multi-protein complexes at the nanometer scale. Using single-molecule localization microscopy, the precise location of a stochastically activated population of photoswitchable fluorophores is determined during the collection of many images to form a single image with resolution of ~10–20 nm, an order of magnitude improvement over conventional microscopy. However, the spectral resolution of current SRM techniques are limited by existing fluorophores with only up to four colors imaged simultaneously, limiting the number of intracellular components that can be studied in a single sample. In the current work, a library of novel BODIPY-based fluorophores was synthesized using a solid phase synthetic platform with the goal of creating a set of photoswitchable fluorophores that can be excited by 5 distinct laser lines but emit throughout the spectral range (450–850 nm) enabling multispectral super resolution microscopy (MSSRM). The photoswitching properties of all new fluorophores were quantified for the following key photoswitching characteristics: (1) the number of photons per on cycle (2) the number of on cycles (switching events), (3) the percentage of time the fluorophore spends in the fluorescent on and off states, and (4) the susceptibility of the fluorophore to photobleaching (time of last event). To ensure the accuracy of our photoswitching measurements, our methodology to detect and quantitate the photoswitching properties of individual fluorophore molecules was validated by comparing measured photoswitching properties of three commercial dyes to published results.1 We also identified two efficient methods to positionally isolate fluorophores on coverglass for screening of the BODIPY-based library.

Keywords: super resolution microscopy, photoswitch, fluorophore, BODIPY, polyvinyl alcohol, polyacrylamide

1. INTRODUCTION

Super resolution microscopy (SRM) has overcome the historic spatial resolution limit of light microscopy, enabling fluorescence visualization of cellular structures and multi-protein complexes at the nanometer scale. Using single-molecule localization microscopy, the precise location of a stochastically activated population of photoswitchable fluorophores is determined during the collection of many images to form a single image with resolution of ~10–20 nm, an order of magnitude improvement over conventional microscopy.2 However, the spectral resolution of current SRM techniques are limited by existing fluorophores with only up to four color simultaneous fluorescence emission based imaging currently possible, limiting the number of intracellular components that can be detected in a single sample. Current fluorophores limit the spectral resolution of SRM because of their excitation maxima vary widely, gaps exist in the emission spectra space, and their photoswitching and optical properties differ greatly making some colors more difficult to resolve than others.

A library of novel BODIPY-based fluorophores was synthesized using a solid phase synthetic platform to create a set of photoswitchable fluorophores with the goal of creating a photoswitchable fluorophore library that can be excited by 5 distinct laser lines that emit throughout the spectral range (450–850 nm) enabling MSSRM. The photoswitching properties of all new fluorophores were quantified for the following key photoswitching characteristics: (1) the number of photons per on cycle, (2) the number of on cycles (switching events), (3) the percentage of time the fluorophore spends in the fluorescent on and off states, and (4) the susceptibility of the fluorophore to photobleaching (time of last event). In general, image resolution is improved as the photons per switching cycle increases and the percentage of time the molecule spends in the fluorescent state decreases.1 The image quality improves with increased number of switching events and a decreased susceptibility to photobleaching or longer last event times because there are more opportunities to localize the fluorophore molecule.1

Prior to screening the BODIPY-based fluorophores, our methodology to detect and quantitate the photoswitching properties of individual fluorophore molecules was validated. Validation was completed by conducting photoswitching property analysis of three commercially available fluorophores with published photoswitching properties.1 The sample preparation, imaging collection, and photoswitching analysis was completed to replicate the conditions used to attain the published results to make the most accurate comparison.

In addition to validating our photoswitching quantification method, a high throughput screening method was needed to evaluate the photoswitching properties of the BODIPY-based library. The technique used by the reference1 and in our validation was to conjugate the NHS ester form of each fluorophore to an antibody and adsorb them to coverglass before imaging. Although this is a feasible method for positional isolation for NHS ester activated dyes, a screening method that doesn’t require NHS ester activated fluorophores is desirable for broad applicability to other commercial molecules as well as novel fluorophores such as the BODIPY-based library. An ideal screening method would eliminate the necessary NHS ester activation and antibody conjugation steps. Three alternative methods to positionally isolate fluorophore molecules for photoswitching measurements were evaluated in the completed studies. These included using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyacrylamide carboxyl modified (PAC), which do not require NHS ester functionality and conjugation to antibodies. PVA is commonly used as a mounting media on coverglass and has been used to study fluorophores by single molecule switching microscopy.3 PAC is typically used to form gels for electrophoresis, but also forms a solid film on coverglass when not adequately hydrated. The texture variability of PAC based on hydration could potentially be used to modify the screening method to include multiple types of fluorophores fixed in various locations within the same PAC gel block.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Coverglass preparation

Eight-well chambered coverglass (Lab Tek) was washed before adding dye molecules as follows: 5 min 0.5% v/v Sparkleen detergent solution, 3 × 5 min 0.2 μm filtered water, 90 min 1 M potassium hydroxide, and 3 × 5 min 0.2 μm filtered water. Cleaned wells were stored in 0.2 μm filtered water until use.

2.2. Dye-antibody conjugation and adsorption to prepared coverglass

Three commercial fluorophores with published photoswitching properties1 were used to validate the sample preparation, imaging conditions, and imaging method. Atto 488 (ATTO-TECH), Cy3B (GE Life Sciences), and Alexa Fluor 647 (Life Technologies) were selected to test the 488 nm, 561 nm, and 647 nm laser lines, respectively, of the SRM. To fix the dye molecules in place for imaging the NHS ester versions of each fluorophore was conjugated to donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in a 1:1 dye to protein ratio. The final fluorophore to antibody ratios were calculated using Beers Law and absorbance maxima measurements at 280 nm to quantify protein and 500, 560, and 650 nm to quantify Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647 concentrations, respectively. The resulting conjugation ratios were as follows: 0.63 for Atto 488, 0.33 for Cy3B, and 0.41 for Alexa Fluor 647. A fluorophore to antibody ratio of less than 1:1 was desirable to aid in accurate resolution of individual fluorophore molecules. Sparse coverglass labeling was achieved by incubating dye-conjugated antibodies at 1×10−12 moles of fluorophore in 200 μl of 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) per washed well for 16 hours at room temperature.

2.3. Additional methods to positionally isolate fluorophore molecules: streptavidin-biotin, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and polyacrylamide carboxyl modified (PAC)

The same three commercial dyes, Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647, were used to evaluate three additional methods to positionally isolate fluorophore molecules for photoswitching measurements: streptavidin-biotin (strept-biotin), PVA, and PAC. The strept-biotin method consisted of conjugating the NHS ester fluorophore molecules to streptavidin (Life Technologies) using similar methods to the antibody conjugation methods described above. The conjugation reactions were set up in a ratio of 1:1 dye to streptavidin and resulted in the following dye to streptavidin ratios: 0.30 for Atto 488, 0.12 for Cy3B, and 0.22 for Alexa Fluor 647. The final ratios were again calculated using Beers Law and absorbance maxima measurements at 280 nm for streptavidin and the absorbance maxima for each fluorophore as listed above. Wells of the washed chambered coverglass were treated with biotinylated bovine serum albumin (biotin BSA, Sigma) and BSA (Omni Pur) prior to adding the dye-conjugated streptavidin molecules. The BSA/biotin BSA solution incubated in the washed wells consisted of 1 mg ml−1 BSA and 0.01 mg ml−1 biotin BSA. Each well was incubated with 200 μl of the BSA/biotin BSA solution for 30 min, followed by three washes with 1x PBS. The dye-conjugated streptavidin molecules were incubated with the BSA/biotin BSA coated wells immediately following PBS washing for 90 min protected from light. The dye-conjugated streptavidin molecules were incubated with 2×10−10 moles fluorophore per well in 200 μl 1x PBS to facilitate accurate separation of single fluorophore molecules for imaging.

The PVA (Fisher Science) and PAC (Acros Organics) were each dissolved in 1x PBS to 2% w/v solutions and stored at room temperature. Samples were prepared with 1×10−12 moles fluorophore in 200 μl of 2% w/v PVA and 2% w/v PAC. The samples were added to wells and left in a hood to dry to a solid film on the washed chambered coverglass overnight protected from light.

2.4. Preparation of imaging buffer

Imaging buffer was used to create the appropriate oxidation-reduction (redox) conditions to promote the selected fluorophores to photoswitch.1,4 The imaging buffer was made in three parts, which were mixed immediately before imaging experiments. Part 1 consisted of 20% w/v glucose in Tris–buffered saline (TN) made with 50 mM Tris pH 8.0 and 10 mM NaCl. Potential solid precipitates were removed by centrifugation after which the supernatant was removed for use. Part 1 of the imaging buffer solution was stored at room temperature. Part 2 consisted of 1 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase and 80 μg ml−1 catalase in TN buffer. Part 2 of the imaging buffer was also centrifuged to remove solid precipitates and the supernatant was stored at 4°C for up to one week. Part 3 consisted of 1 M β-mercaptoethylamine (MEA), with the pH adjusted to 8, and stored at 4°C for up to one week. The imaging buffer mixture was made of 250 μl Part 1 + 250 μl Part 2 + 10 μl Part 3 to image a single well. The final concentrations of the oxidizing components of the imaging buffer were 0.5 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 40 ug ml−1 catalase and 10% w/v glucose. The final concentration of the reducing component of the imaging buffer was 10 mM MEA.1 For the fluorophore conjugated antibody and fluorophore conjugated streptavidin preparations, the low concentration protein conjugated fluorophore solution was removed prior to adding imaging buffer for imaging. Any protein-conjugated fluorophore not positionally isolated by adsorption or biotin binding was removed by washing the well three times with 1x PBS. The wells were additionally flushed with 1x PBS if visible debris appeared in the background upon microscopic inspection, followed with the addition of fresh imaging buffer mixture.

2.5. Image collection

Imaging was completed on a Nikon ECLIPSE Ti-U inverted microscope with a 60x oil immersion objective. Atto 488 molecules were excited with a 488 nm laser at a fluence rate of 0.36 kW cm−2 (Coherent Sapphire), Cy3B molecules were excited with a 561 nm laser at a fluence rate of 0.75 kW cm−2 (Opto Engine), and Alexa Fluor 647 molecules were excited with a laser at a fluence rat of 0.27 kW cm−2 (Coherent OBIS). EMMCD cameras (Photometrics Evolve Delta and Andor iXon Ultra) were used to collect images of Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647 molecules in a 512 × 512 pixel area field of view. All images were collected with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) configuration of the light path. Three image series of each fluorophore sample were collected, with each image series in a different area of the prepared sample. Each image series consisted of 5000 frames taken at 7 frames per second. The EMCCD gain was adjusted for best contrast of the fluorophore molecules.

2.6. Photoswitching analysis of fluorophore molecules

Particles (individual fluorophores) were identified that were at least 8 times the root mean square (RMS) of the average detected signal and were tracked throughout the 5000 frame image series. At least 100 particles were identified for each image series. MATLAB code was designed to analyze the images to quantitate the photoswitching properties of each particle in each 5000-frame image series. Three image series of each fluorophore sample were assessed to report an average and standard deviation for each fluorophore and positional isolation method. The photon number was calculated by converting the signal from an identified and tracked particle to a photon number based on the EMCCD cameras’ measured gain and gain setting with the imaging collection software during image acquisition. The photons per switching event were calculated by adding the photons from consecutive frames from the particles emitting signal above the set threshold. The number of switching events was determined by counting the number of times a tracked particle emitted photons higher than 8 times the RMS of the average detected signal. The percentage of time each dye molecule fluoresced was calculated between 400–600 s of the collected image series so a direct comparison could be made with the reference1 values. The average number of frames each dye molecules photoswitched was determined by tracking each particle from the last frame and recording when photons were first emitted above 8 RMS.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Validation of photoswitching property analysis method

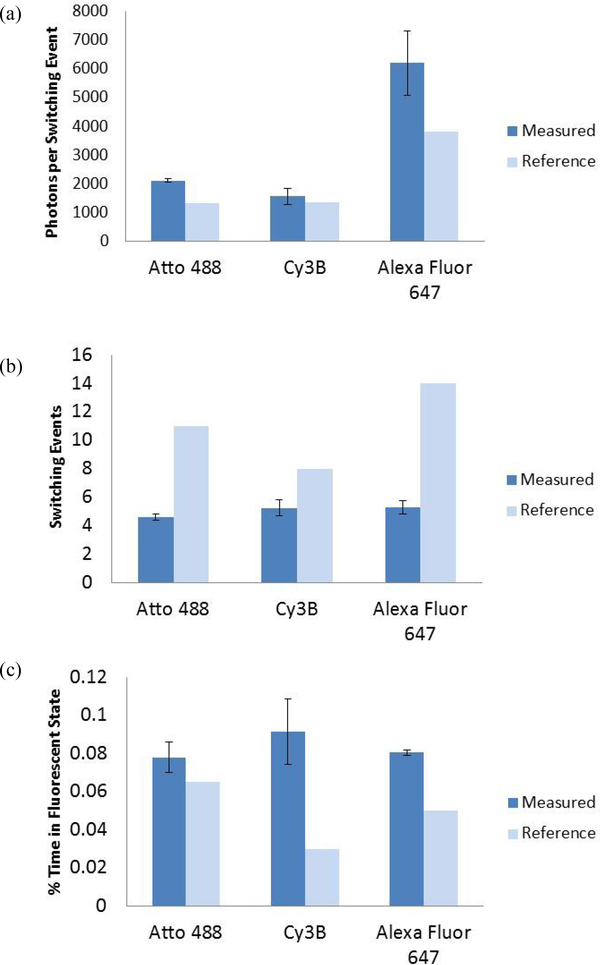

The photons per switching event, number of switching events, and percentage of time the molecule spends in the fluorescent state were determine for Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647 molecules that were adsorbed to coverglass via antibody conjugation. The measured photons per switching event for Atto 488 and Cy3B were both near 1500 photons while Alexa Fluor 647 emitted near 6000 photons (Figure 1a). The total number of switching events measured was similar for all three fluorophores, each with at least four switching events over 5000 frames (Figure 1b). All measured values of the percentage of time spent in the fluorescent on state were less than 0.1% of the total imaging time (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Measured values of photoswitching properties compared to reference1 values for Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647. Individual fluorophore molecules were fixed by adsorbing the fluorophore-conjugated antibodies to coverglass. The measured values are shown as the mean value from the three videos ± the standard deviation. a) Photons per switching event per single fluorophore molecule. b) The number of switching events. c) Percentage (%) of time in the fluorescence on state.

Comparing the photons detected per switching event per dye molecule in Figure 1a with the published values, the measured photon output values followed the same trend over the three tested fluorophores as the reference1 values. Specifically, Alexa Fluor 647 was the brightest; with Atto 488 and Cy3B having similar lower photon output values. The measured number of switching cycles for the three tested fluorophores was not an exact match to the absolute values of the reference1 (Figure 1b). The measured values for the amount of time the fluorophores spent in the fluorescent on state for the Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647 dye molecules were higher than the reference1 values, but in a similar range (Figure 1c).

The sample preparation, image collection, and data processing methods were conducted in the current study to balance replicating the conditions used to determine the reference1 values with conditions that were most suitable with our super resolution microscope hardware and software setup. While the same dyes, antibody dye-fixing method, and imaging buffer recipe as the reference1 were used for the comparisons made in Figure 1, there were several notable differences. First the fluence rates of the three lasers were less than the reference1 values. The reference1 used laser fluence rates of 1.2 kW cm−2 for 488 nm, 2.2 kW cm−2 for 561 nm, and 0.8 kW cm−2 for 647 nm while our setup had fluence rates that were about three times lower with 0.36 kW cm−2, 0.75 kW cm−2, and 0.27 kW cm−2 for 488 nm, 561 nm, and 647 nm respectively. Second, there were also some differences related to image data analysis. The reference1 values were calculated from particles that were detected in the first frame that were 4 times the standard deviation of the fluctuations of the detected background signal, while our MATLAB code processed particles that were detected throughout the entire 5000 frame image series collection that were at least 8 times higher than the RMS of background fluctuations. The denoted difference in laser power and image data analysis likely account for the minor dissimilarities between the measured data and the reference data denoted herein. Additionally, it is difficult to determine the repeatability of the reference1 data as only mean values without standard deviation are reported.

Overall the results indicate that the methodology outlined for the current study can be used to accurately detect and quantitate the photoswitching properties of individual fluorophore molecules. This is evidenced by the accurate photon detection of the three dyes (Figure 1a), the determination that all three dyes photoswitched at least 4 times (Figure 1b), and that they fluoresced for less than 0.1% of the 5000 frame image series (Figure 1c).

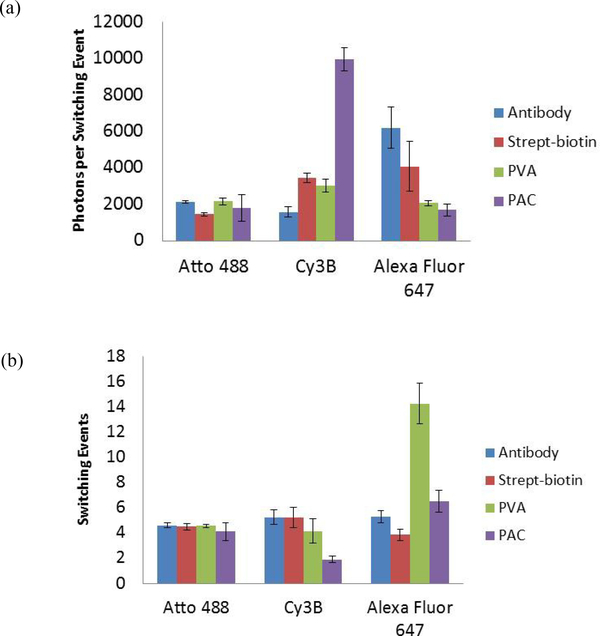

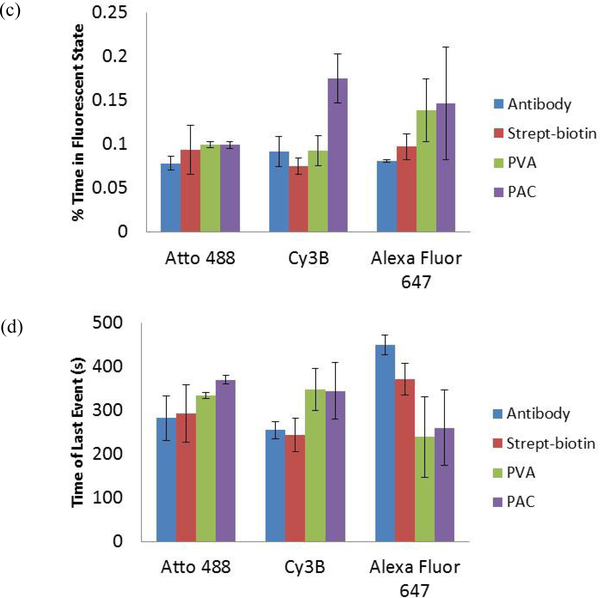

2.2. Evaluation of fluorophore isolation methods for quantitation of fluorophore photoswitching properties

Four methods to fix fluorophore molecules to coverglass were evaluated to determine if either PVA or PAC could be used as a high throughput screening method to assess the photoswitching properties of fluorophore without NHS ester activation. The fluorophore molecules were fixed to coverglass with antibodies, stept-biotin, PVA, and PAC. Three photoswitchable dyes were used for this evaluation including Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647. The photoswitching properties of single dye molecules were assessed by quantifying the photons per switching event (Figure 2a), the number of switching events (Figure 2b), the percentage of time the fluorophores spent in the fluorescent on state (Figure 2c), and the time of the last switching event (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

The four methods used to fix fluorophore molecules were evaluated by measuring the four photoswitching properties for fluorophores Atto 488, Cy3B, and Alexa Fluor 647. The results are given as the mean value from three videos ± the standard deviation. a) Photons per switching event per single dye molecule. b) The number of switching events. c) Percentage (%) of time in the fluorescence on state. d) Time of last event.

Comparison of the antibody fixation method (blue bars) to the strept-biotin method (red bars) demonstrated little variability in the photoswitching results between the antibody and strep-biotin methods (Figure 2). This indicated that the photoswitching results were not dependent specifically on adsorbing fluorophore-conjugated antibodies directly to coverglass.

The PVA and PAC data (green and purple bars, respectively) were compared to the validated data collected with the fluorophore-conjugated antibody method. All three dyes photoswitched while fixed in solid PVA and PAC films on the coverglass. The photoswitching properties of Atto 488 did not change significantly across the four fixing methods. However, there was more variability in some of the photoswitching results for Cy3B and Alexa Fluor 647. Specifically, for Cy3B in PAC the photons per switching event were significantly higher than the other fixing methods (Figure 2a), there were fewer switching events (Figure 2b), and Cy3B spent more time in the fluorescent on state when prepared in PAC compared with other fixation methods (Figure 2c). For Alexa Fluor 647 the photons detected per switching event were significantly lower when fixed in PVA and PAC than the other methods (Figure 2a) and the number of switching events was higher in PVA compared with other fixation methods (Figure 2b).

While there is variability in results for two of the three tested fluorophores, PVA and PAC methods clearly demonstrated photoswitching can be measured without NHS ester activation of the fluorophores. The PVA and PAC methods can be used to screen for photoswitching properties since sample preparation is more efficient than ensuring the fluorophores of interest have the necessary NHS ester functionality before completing conjugation reactions to antibodies. Once fluorophores are screened with PVA or PAC, promising fluorophores can be studied further using the antibody technique before testing in cells if desired.

Controls of 2% w/v PVA and PAC without added fluorophore did not have signal that interfered with single molecule photoswitching detection and measurements.

4. CONCLUSION

We have validated our methodology to detect and quantitate the photoswitching properties of individual fluorophore molecules. Using three commercial dyes including Atto 488, Cy3B and Alexa Fluor 647, and an antibody dye-fixing method, we demonstrated that detection of photon number, total switching events, and fluorescence on time is similar to the published results1. We also determined fluorophore fixation methods to screen photoswitching properties of fluorophores without addition of a NHS ester functionality for conjugation to antibodies. PVA and PAC did not prevent fluorophore photoswitching and gave results comparable to the original antibody dye-fixation method. Commercially available fluorophores and novel fluorophores without NHS ester activation can be easily mixed into liquid PVA or PAC, dried to a film on coverglass, and imaged for efficient photoswitching analysis.

REFERENCES

- [1].Dempsey GT, Vaughan JC, Chen KH, Bates M & Zhuang X Evaluation of fluorophores for optimal performance in localization-based super-resolution imaging. Nature methods 8, 1027–1036, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Heilemann M, van de Linde S, Mukherjee A & Sauer M Super-resolution imaging with small organic fluorophores. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 48, 6903–6908, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Belov VN, Bossi ML, Folling J, Boyarskiy VP & Hell SW Rhodamine spiroamides for multicolor single-molecule switching fluorescent nanoscopy. Chemistry 15, 10762–10776, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].van de Linde S et al. Direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy with standard fluorescent probes. Nature protocols 6, 991–1009, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]